The recent UK election results have added to tensions in the North of Ireland, delivering a blow to the DUP and boosting demands for a border poll. Only a united working-class struggle can offer a way forward.

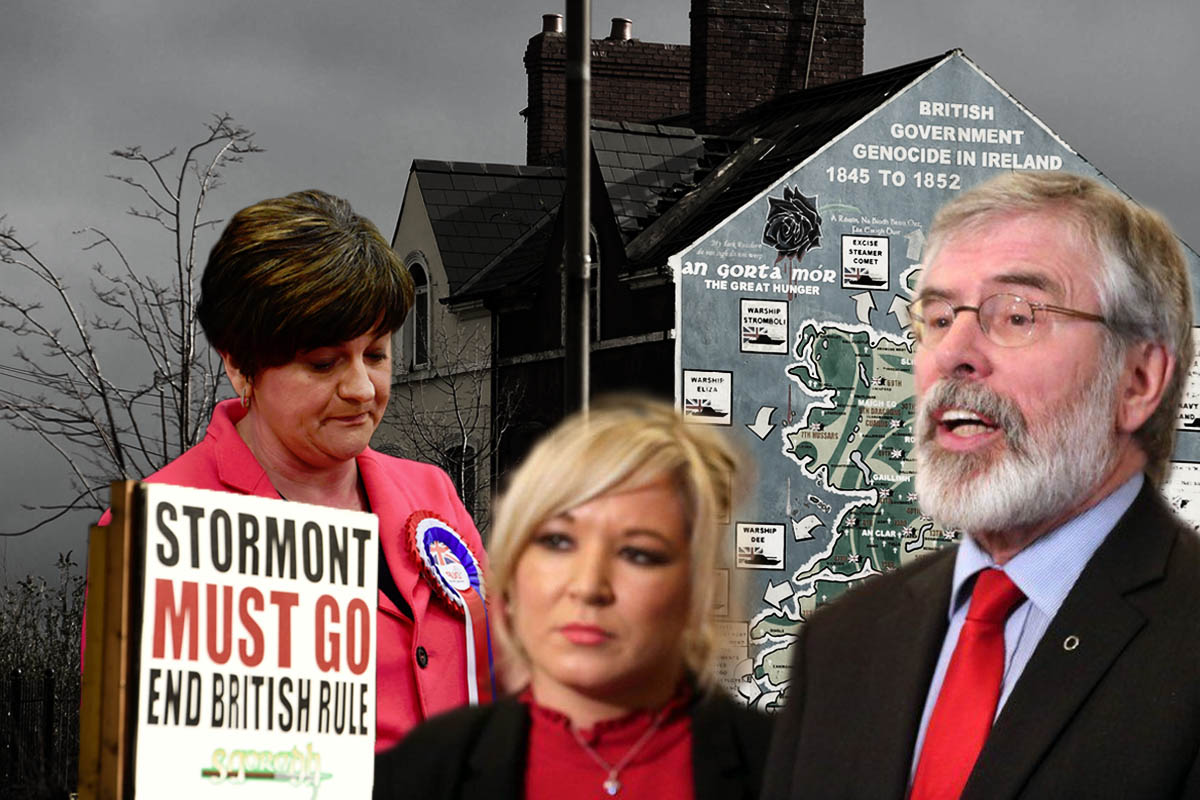

The focus of coverage of the 12 December general election has naturally been on the gains made by the Tories, particularly in the Midlands and the North of England. Less attention has been given to the seismic shift that took place in the North of Ireland. In an election marked by sectarianism, electoral alliances, Brexit and the border, the DUP received a hammering. Their fall from the position of kingmakers at Westminster two years ago has been dramatic.

For the first time in its history, the North of Ireland has returned less unionist MPs than nationalist MPs. Sinn Féin are insisting that these results show that there is no longer a clear majority for the North of Ireland remaining in the union. But with a Tory majority at Westminster, a border poll is unlikely in the near term to say the least.

The DUP had a devastating night. It is clear that they were punished for their role at Westminster and the debacle of Brexit. They also suffered as a result of widespread tactical voting, with pro-Remain parties forming pacts across the North. However, these elections point to a deeper rot within unionism. The period which now opens up in the North is one of extreme instability.

Bye-bye DUP

In 2017 the DUP strutted into Downing Street as kingmakers. For the princely sum of £1 billion, Arlene Foster and her party placed Theresa May back in power.

In 2017 the DUP strutted into Downing Street as kingmakers. For the princely sum of £1 billion, Arlene Foster and her party placed Theresa May back in power.

To say the DUP were unsuccessful in using their unexpected 15 minutes of fame to “protect our precious union” would be the understatement of the century. Having rejected May’s deal, they ended up with Boris’ deal – and the promise of a border in the Irish sea. And with the Tories now having a clear majority, there is not a thing they can do about it either. From kingmakers they have been relegated to an irrelevance once again.

Before the election, Johnson’s proposed deal came as a massive jolt to loyalists. Having spoken at DUP conferences, painting himself as a defender of the union and everything British, he now showed his true colours: Boris is a political opportunist who is resting on a narrow, little-Englander, Tory base. 59% of these people would be happy to see Northern Ireland leave the UK to “Get Brexit Done”. 63% would also be happy to see Scotland go on its merry way. 54% of Tory Party members even think the destruction of the Tory Party itself is a price worth paying!

Alarmed loyalists – from the DUP to the Orange Order, to the previously feuding factions of the UDA and the UVF – responded with meetings in Orange Lodges and Con Clubs around the North to discuss how to respond to the sudden threat of an “economic united Ireland”. A hardcore at these meetings were up for a fight, promising “resistance” on the streets of Northern Ireland if Boris’ deal passed.

Going into the election, this was the main message of the DUP: vote for us to stop this threat of a united Ireland (and the violence that they and their friends would whip up if such a thing came to pass)! In meetings with leaders of the UDA and the UVF before the election, the loyalist paramilitaries were drafted in to “get the vote out”.

To ensure the DUP didn’t face any serious challenges from other unionist parties that might “split the vote”, one of the first moves of these gangsters was to smash up the headquarters of the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) in North Belfast. By such means were the latter “persuaded” to stand aside to prevent a defeat for Nigel Dodds – seen by many as the power behind the throne in the DUP. What a fall from grace for the UUP, once the dominant party of the Protestant bourgeoisie!

But despite pulling out all the stops, nothing could prevent a catastrophe for the DUP on the night. Dodds lost his seat to Sinn Féin’s John Finucane. This was despite a grim, paramilitary-led campaign shot through with sectarianism. Finucane is the son of human rights lawyer, Pat Finucane, who was murdered by loyalist paramilitaries in front of his family in 1989 with the collusion of the British state. Unironically the DUP’s paramilitary canvassers saw fit to put up banners with the words: “The real Finucane family: steeped in the blood of our innocents.”

In North Down, the main competition the DUP were facing was the Alliance Party. Across the constituency, posters declaring “The Unholy Alliance: If you vote for them IRA win!” were plastered around. And yet Alliance registered a 35 point swing to take the seat. This represents a political earthquake. Ten years ago this predominantly Protestant constituency saw unionist parties take 90% of the vote. Now it is represented by a party that takes a neutral stance on the national question.

Despite Alliance’s liberal character, their rise – particularly among young and Remain-voting Protestants – shows that there is a tiredness with sectarian politics among a layer. Disillusioned with the established unionist parties, these layers are looking for an alternative. With Brexit colouring this whole election, the liberal, pro-Remain Alliance Party have temporarily and partially filled this vacuum.

This places into sharp relief how the DUP, resting on an increasingly narrow and sectarian base, can no longer take for granted that the stick of the IRA and a united Ireland will corral voters around them. The IRA are long gone. And people today face far worse things than a united Ireland: things for which the DUP has no answers. People are becoming tired of the same old message, which is trotted out on both sides of the sectarian divide in election after election: “vote for us or the other lot will get in.”

A Remain alliance

It wasn’t just on the unionist side that these elections saw unusual political lash-ups. The two main nationalist parties, Sinn Féin and the SDLP, along with the Greens, formed the core of a “Remain alliance”.

It wasn’t just on the unionist side that these elections saw unusual political lash-ups. The two main nationalist parties, Sinn Féin and the SDLP, along with the Greens, formed the core of a “Remain alliance”.

Above all, this election was marked – in the North of Ireland as in Britain – by the question of Brexit. In the 2016 referendum, 56% of people in the North of Ireland voted to Remain. However, this figure masks a deep division with a majority of nationalists voting for Remain and a majority of unionists voting to Leave, with the DUP campaigning enthusiastically for the latter.

In North Belfast, where there is a fine balance between Catholics and Protestants in the constituency, Sinn Féin focused on targeting the leafier, mixed, middle-class, Remain areas whose voters might previously have voted SDLP and who could swing the seat.

As Finucane reassured his constituents: “Does voting for me mean they become Sinn Féin voters and supporters? Of course not […] They see this election for what it is. It’s about maximising that Remain voice.” To which Colum Eastwood, SDLP leader, replied: “It’s better to have Finucane in his house than Nigel Dodds in the House of Commons.”

The question of tactical voting has now placed a question mark over the rationale of Sinn Féin’s abstentionist policy. In some areas, Sinn Féin even went as far as to advocate voting tactically for Alliance or even the “independent unionist” and former UUP member, Sylvia Hermon!

Despite having won some seats, this “Remain alliance” hasn’t benefited Sinn Féin in the least bit. Across the North their vote dropped by 6.7%. This wasn’t just down to their standing down in East Belfast and North Down. They were also punished in other places that they previously held such as Foyle where there was a 19 point swing to the SDLP, handing them the seat.

If the point of voting tactically is to maximise the Remain voice in Parliament, many people will be asking, “why vote for a Remain party that won’t take up its seats when you can just vote for an equally Remain party that will take its seat?”

A crisis of unionism

By any measure, the result of this election was remarkable. Unionism – which lost its majority in the Stormont elections in 2017 – is once more confirmed in its deep and intractable crisis.

By any measure, the result of this election was remarkable. Unionism – which lost its majority in the Stormont elections in 2017 – is once more confirmed in its deep and intractable crisis.

Demographic change can explain part of the picture. In education and in employment, Catholics now represent a majority of the population. The fact that nationalist parties now occupy three of the four seats in Belfast is particularly striking for anyone who knows the history of that city.

But there is another side to the question: the crisis of capitalism is translating into a crisis of unionism. Ever since partition, Protestant bosses have tried to create the illusion of a community of interests between themselves and Protestant workers. This holds little water in the post-2008 world. In an era of austerity, parties like the DUP have nothing left to offer other than sectarian fear-mongering, raising the bogeyman of the IRA and the “horrors” of Irish unification.

The result has been a polarisation. In the unionist camp, the most vile and sectarian elements have come to dominate as the filth of this election shows. Into the struggle for existence that capitalism creates, they inject their own sectarian poison, misdirecting the despair and anger of some of the most downtrodden and oppressed layers of poor Protestants against poor Catholics. For many who voted to leave the EU in 2016, like in England and Wales, it was a question of tipping over the applecart and kicking back against the entire establishment.

Meanwhile, many of the most advanced workers and youth are repelled by this sectarian baiting. Added to this, a large layer of middle-class Remain voters, having something to lose, look at the Brexit debacle with growing alarm.

A revival of Stormont?

The poor results for the DUP and Sinn Féin are now going to pile the pressure on both parties to return to negotiations aimed at reviving Stormont. For nearly three years now, the North of Ireland has been left without any government.

The poor results for the DUP and Sinn Féin are now going to pile the pressure on both parties to return to negotiations aimed at reviving Stormont. For nearly three years now, the North of Ireland has been left without any government.

Neither party has a clear way forward. When Sinn Féin collapsed the executive back in 2017, they did so on the back of growing anger among the public at Stormont. Years of austerity, the stench of scandal surrounding the DUP, and the increasing sectarianism of the latter meant that Sinn Féin’s move enjoyed a certain popularity at that time. It’s clear now, however, that they didn’t have any intention of building a mass movement outside of Stormont – and in fact didn’t have any plan whatsoever.

In the years since the Northern Ireland Assembly collapsed, living conditions for poor and working-class people in the North have continued to deteriorate. The NHS has continued to crumble. Meanwhile the absentee politicians have continued to claim their wages. The lack of a working executive has largely been blamed for all of this. Certainly the media and politicians in London and Dublin have been keen to use this state of affairs as a lever to try and get the Assembly back up and running.

Failure to do so would now mean new Assembly elections in the spring. Neither Sinn Féin nor the DUP relish this prospect as they reflect on the heavy blows they’ve received at these elections.

In such circumstances, it is not ruled out then that the two could manage to cobble together some sort of agreement. Such an outcome is doubtful, however, as Sinn Féin will require some concession to justify their move (an Irish Language Act for instance). Meanwhile the DUP, resting on a sectarian crutch, would be reticent to make concessions.

Even if such an agreement does come to pass, it won’t fundamentally solve anything. For ten years up until 2017, the two big parties jointly applied austerity policies. Indeed, this was part of the reason that the Assembly collapsed in the first place. Back in 2015, Sinn Féin had essentially agreed to apply Tory austerity in return for the devolution of corporation tax, so that they could lower tax rates in an effort to attract big business to Northern Ireland!

They were facing growing discontent in working-class, Catholic communities, reflected for example in shock victories for the left-wing party, People Before Profit. In essence, it was this that lead Sinn Féin to collapse the executive. Having abandoned the cul-de-sac of individual terror in the 1990s, Sinn Féin chose the cul-de-sac of reformism. Now that has failed too, the question socialist Republicans must ask is: where next?

Towards a border poll?

For Sinn Féin, the answer is a border poll. It would certainly seem, on the basis of these elections and recent polls, that such a poll could deliver a majority for Irish unification.

For Sinn Féin, the answer is a border poll. It would certainly seem, on the basis of these elections and recent polls, that such a poll could deliver a majority for Irish unification.

But this rests on the illusion that the British ruling class will allow a democratic, constitutional solution of the national question in Ireland in the first place. The leadership of Sinn Féin have pointed out that the grounds for such a poll are written into the text of the Good Friday Agreement. But it will be a cold day in hell before the Tories call any such thing. Having a majority in Parliament, they are under no obligation to do so.

It might be argued that the British ruling class has no sound economic or strategic reason for holding onto the North of Ireland anymore. This is correct. However, there are deeper issues for the ruling class.

With the Conservative and Unionist Party having been taken over by the “Tory Taliban”, there will be no question of Boris Johnson ruling from the vantage point of some “enlightened liberalism”. Playing to his base, he will be forced to wrap himself in the Union Jack and lash out like a berserker at any threat to “our precious union”.

And it is not only in the North of Ireland that the British ruling class faces a resurgent national question. More worryingly for them, they face a growing mood for independence in Scotland. To grant a poll in Ireland will only increase the clamour for a new poll in Scotland.

In both cases they have one card up their sleeves which they have played time and again in moments of crisis: the Orange card. It is not ruled out that they might whip up loyalist sectarianism once again.

The ruling class has never played by the rules of constitutional “fairness”. In 1913, faced with a Home Rule bill in Parliament, the Tories in opposition gave full support to the arming of lumpen loyalist gangs under the leadership of Lord Carson to stop Irish independence in its tracks. In 1914, senior officers at the Curragh military base even mutinied against moves by the Liberal government to intervene.

During the Troubles we saw even more underhand methods. Former MI5 agents have claimed that the British state actually promoted the 1974 Ulster Workers Council strike (a “strike” against the Sunningdale Agreement, primarily enforced by loyalist paramilitaries) as a means of undermining the Wilson Labour government.

Has the British ruling class changed its spots? Of course not. It is worth noting how Boris Johnson has wasted no time in dropping charges against Soldier F and other Armed Forces personnel involved in atrocities during the Troubles. By whipping up sectarianism once again, the ruling class could render a border poll impossible. Using the threat of civil strife and sectarian violence, they would kick such a poll into the long grass to “prevent violence”.

The ruling class in the South of Ireland are, if anything, more hostile to Irish unification! Leo Varadkar was quite open about this in his first interview after the election on 13 December. The Irish bourgeoisie see no economic benefit for them in unifying Ireland. On the other hand, they have everything to gain from a cosy relationship with British capitalism. Furthermore, there is a growing anger in the depths of society in the South. They will have no desire, under these circumstances, of throwing open the entire constitutional basis of the state.

Fight for a socialist united Ireland!

Sinn Féin has based its campaign for unification in recent years on a peaceful, constitutional road, based on appealing to the middle class. For the majority, economic and social conditions continued to get worse after the Good Friday Agreement (GFA). For a thin layer of the population, however, things did improve. Aided by government and EU disbursements and a booming economy, a stratum of the Catholic population managed to raise itself up to a comfortable, middle-class position. So long as capitalism was booming and the GFA was holding together, this layer concerned itself little with questions like Irish unification.

Sinn Féin has based its campaign for unification in recent years on a peaceful, constitutional road, based on appealing to the middle class. For the majority, economic and social conditions continued to get worse after the Good Friday Agreement (GFA). For a thin layer of the population, however, things did improve. Aided by government and EU disbursements and a booming economy, a stratum of the Catholic population managed to raise itself up to a comfortable, middle-class position. So long as capitalism was booming and the GFA was holding together, this layer concerned itself little with questions like Irish unification.

But now Brexit has made things extremely uncertain for them. Meanwhile, the South presents an apparently different picture. The economy is booming – although it doesn’t feel like a boom for the ten thousand men, women and children sleeping rough on the streets of the “Republic of Opportunity” – and the grip of the Catholic Church has been loosened.

This has led to a certain radicalisation in favour of Irish unification and an increasing warmth towards the idea of a border poll among middle-class Catholics in particular. It is to this moderate, middle-class, nationalist layer in the leafy suburbs that Sinn Féin has targeted its message: opposition to Brexit; the improvement of democratic rights in the South; the economic benefits of unification under capitalism, etc.

But without a clear class content to their programme, Sinn Féin can offer nothing to working-class Protestants. How can remaining in the EU rectify the horrific social conditions that stalk working-class communities in the Northern statelet? For decades, conditions – for this layer – have only got worse, all whilst Northern Ireland was in the EU!

If a clear class programme is not put forward, the danger would be that a border poll would simply turn into a sectarian headcount, with those fighting for a United Ireland resting on the changed demographics of the region. This would breed resentment, which reactionary forces would seek to harness.

We must offer a clear, class-based alternative to the attempts by the DUP and the Tories to connect with the anger of working-class Protestants and whip up sectarian bigotry. It is not enough to appeal to the “economic sense” of reunification. Such arguments fall woefully short. The majority of the British ruling class got behind a campaign to remain in the EU in 2016 based on it making more “economic sense” than leaving. Needless to say, these arguments were fruitless.

It is over the poisoned social soil of capitalism that the weed of sectarianism flourishes. And this can only be cut down by way of a revolutionary, socialist campaign that offers something to the working class of the whole region.

Capitalism was responsible for the reactionary, sectarian partitioning of Ireland. And it now stands as the main obstacle to Ireland’s reunification today. But a united Ireland cannot be achieved by constitutional means under a middle-class leadership. It will be achieved by a united working-class struggle for socialist revolution or not at all.