In periods of heightened class struggle, art often reflects and amplifies the mood of society.

One of the most striking historical examples is the Dada movement – a radical artistic response to the carnage and decay of capitalist society during and after the First World War.

Today, Dadaism is not widely understood. When it is remembered, it’s often reduced to a bizarre, absurdist precursor to surrealist comedy like Monty Python’s Flying Circus (which used Dada-style montages as the links between sketches), or Vic Reeves and Bob Mortimer’s madcap late-night 90s TV shows.

Perhaps many wouldn’t recognise its influence in the rudimentary collage-art of several 1970s punk record covers – think the Buzzcocks’ single ‘Orgasm Addict’. But such limited views of Dada obscure the deeply political roots of the movement.

Origins

Born in Zurich around the time of the First World War, the Dada movement emerged from a group of artists who had fled the horrors of trench warfare.

From their base at the infamous Cabaret Voltaire – a short walk from Lenin’s residence in exile – artists like Tristan Tzara expressed profound disgust not only at, as they saw it, the absurdity of war, but of bourgeois culture more generally.

The Dada movement was a reaction to the horrors of the meat-grinder taking place in Northern Europe between 1914-1918; with the artists feeling that the war represented a striking illustration of the decline of Enlightenment values.

They correctly saw the war not as an accident, but as the logical outcome of imperialism and capitalist crisis. For them, producing art for the bourgeoisie was akin to collaborating with the system that had created the war in the first place.

However, this sentiment did not find acute political expression for some time. The early works of the Dada movement leaned more towards the existential and nihilistic.

Irrationality and pessimism

Cabaret Voltaire would put on evenings of poetry readings which used only made up words, such as Karawane, a ‘sound poem’ composed of nonsense syllables. The general point being was to ‘break down language as a tool of rationality’, in a world they saw as evermore irrational.

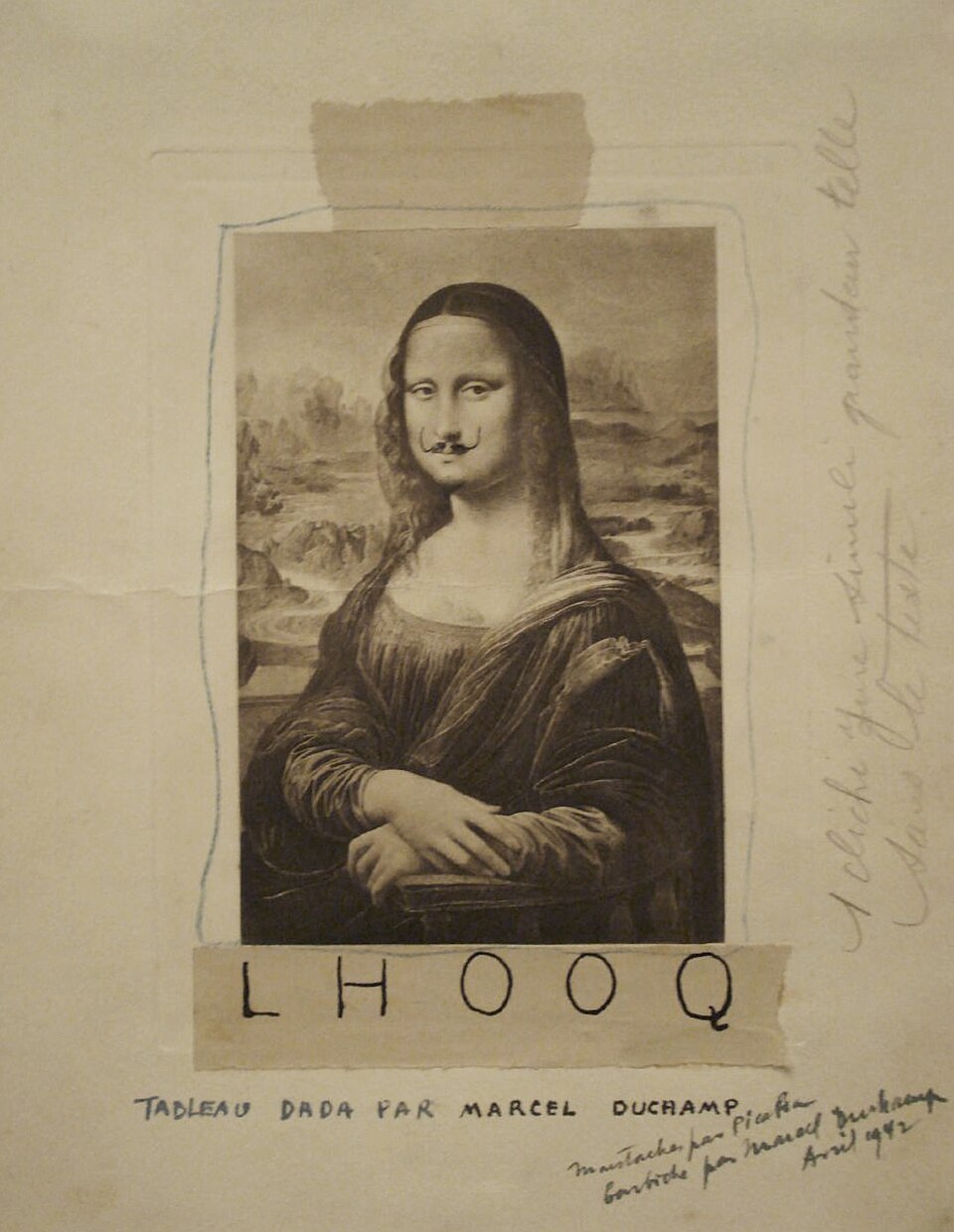

Another early example would be Marcel Duchamp’s LHOOQ which takes a mass-produced, postcard rendering of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, and simply adds a jaunty moustache and goatee beard to it.

The act of desecrating the image is in order to highlight the prior desecration: that of using an artistic masterpiece for the production of cheap postcards; whilst at the same time mocking the ‘iconisation’ of the work.

Other pieces, such as Raoul Hausmann’s Mechanical Head (The Spirit of Our Age), reflects on the dehumanisation of man, turning the inside of a mannequin head into a series of obedient mechanical parts.

Throughout these and many other early Dada works, there existed themes of existential pessimism, mockery of institutions, and reflections of what they saw as the world’s moral bankruptcy. Their art at this time represented more of a scream into the void, rather than a call to arms.

Dadaism’s revolutionary turn

But after the Russian Revolution of 1917, Dada took a sharp political turn. As the movement relocated from Zurich to Berlin, it aligned itself with the burgeoning communist movement there.

While the leaders of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) were attempting to dampen revolutionary fervour with reformist promises, the Berlin Dadaists threw in their lot with the German Communists and the Spartacist Uprising led by Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht.

The movement’s politics were bold and uncompromising. They called for the German workers to unite with the Bolsheviks in Russia, to link together the international revolutionary wave.

The formation of the Central Council of Dada for World Revolution may sound like satire, but their demands were serious: an international revolutionary union of all creative and intellectual people based on radical Communism; automated labor to free up time for creative expression; the expropriation of private property; and communal ownership of public space.

In the first issue of their magazine, Der Dada 1, they called “first and foremost for the international revolutionary union of all creative and intellectual men and women on the basis of radical Communism.”

‘The Art Scab’

In 1920 they held the first Dada Fair (Dada-Messe). The fair not only brought together numerous pieces of art, it was a highly political event that embodied the revolutionary spirit of Berlin Dada, during the immediate aftermath of the failed German Revolution.

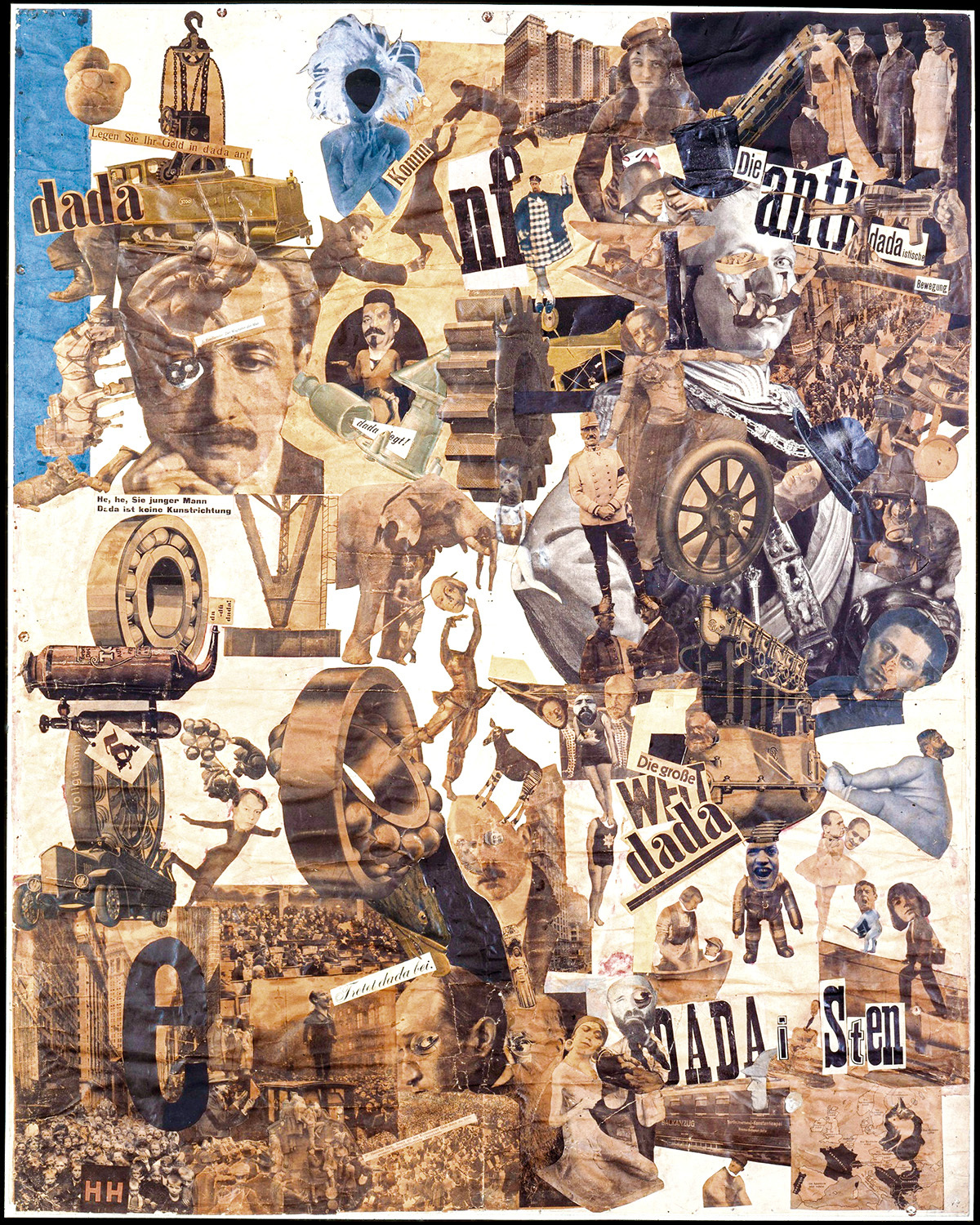

One of the most striking pieces, the awkwardly-named Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany (1919),is a photomontage which at first appears chaotic and confusing.

However, on further inspection, it is possible to make out two clear camps: one corner represents reaction, with photos of the Kaiser, fat grinning capitalists and, significantly, SPD officials.

The other side, where Dada firmly places itself, includes images of Luxemburg, Liebknecht and, for the particularly keen-eyed, Vladimir Lenin. It also portrays women workers and revolutionaries. The piece mocks the bloated capitalists and what it sees as the ‘old guard’ of society – violently slicing a division between them and the revolutionaries portrayed in the opposite corner.

The SPD responded swiftly to the Dada Fair, by banning all Dada publications. Renowned contemporary bourgeois artist Oskar Kokoschka attacked them, stating of the Uprising that he was “more worried about damage to artworks hanging in galleries, than the death of revolutionaries in the street.”

The Dadaists replied with their infamous essay The Art Scab, where they stated: “We welcome it when open struggle between capital and labour takes place where culture and art feel at home – the art and culture that gag the poor, that delight the bourgeois on Sunday, accommodate the oppression of workers on Monday.”

Decline

Sadly, the defeat of the German Revolution led some in the movement to become demoralised. They slumped back into WWI-era existential absurdism. A number of them moved to New York and produced the now en vogue Dada artform for exclusive galleries.

Others remained in Germany and attempted to use art as a propaganda weapon against the rise of the Nazis. Hurrah, die Butter ist Alle! (“Hurrah, the Butter is All Gone!”) shows a German family eating a meal of metal objects, in front of a picture of Hitler and with wallpaper festooned with swastikas.

The title is a reference to Hermann Goring’s infamous declaration that “metal [i.e. guns] will make us powerful; butter will only make us fat” – a militarist sentiment that may well have come from the likes of Keir Starmer or Friedrich Merz today.

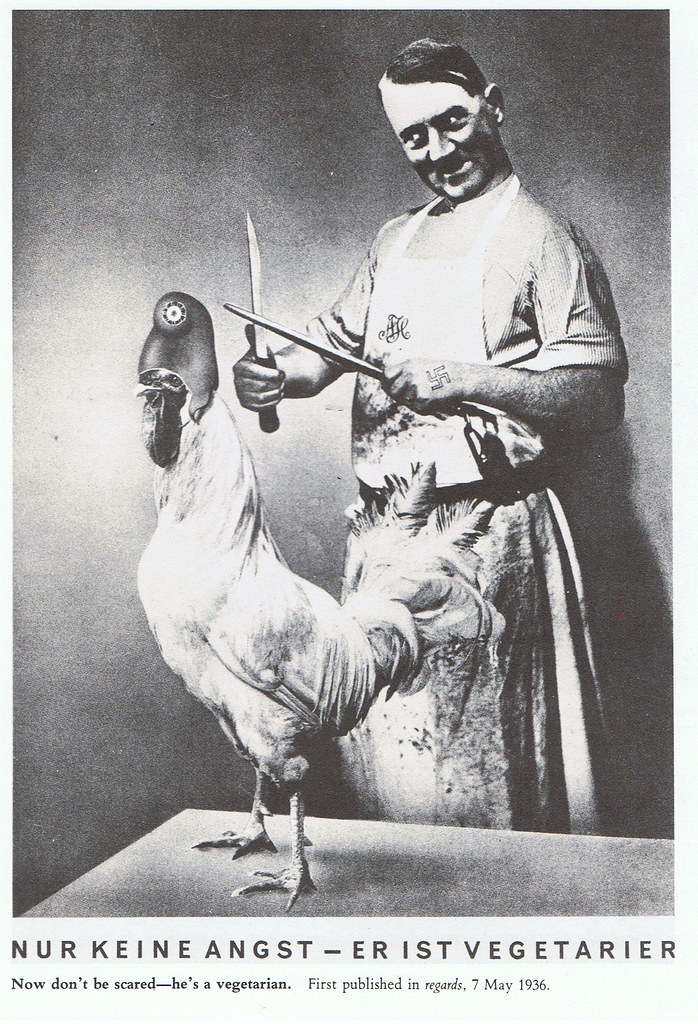

Another piece Now don’t be scared – he’s a vegetarian by John Heartfield is a photomontage which depicts Adolf Hitler grinning and sharpening his knife in anticipation of beheading a gallic rooster.

The title of the piece is a direct quote of the then French Foreign Affairs minister Pierre Laval. It is used to attack the Liberals and centrists who downplayed the dangers of fascism (incidentally, after the war, Laval was tried and executed as a Nazi collaborator).

One prominent Dadaist who did continue to carry forward revolutionary art was Andre Breton, who founded and led the surrealist movement. Breton even co-wrote the Manifesto for Independent Revolutionary Art with Leon Trotsky in 1938.

The tragedy of Dada is that, despite its courage and creative fire, it lacked sustained links with a coherent Marxist programme and outlook. Its energy was explosive, but it could not sustain itself in the face of defeat. But all the combustible material which fuelled Dada is coming back to the surface today.