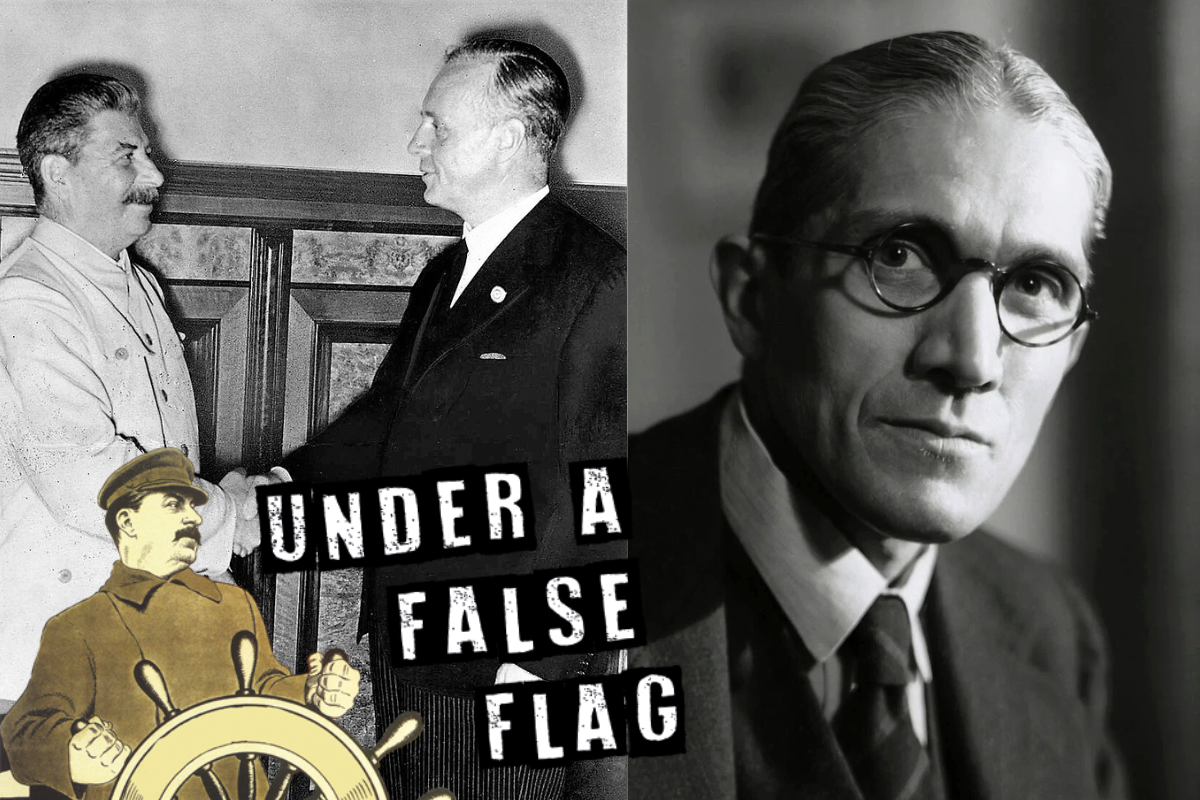

6th June marks the 70th anniversary of the Normandy D-Day landings in 1944. Leaders from across the world have gathered to commemorate the heroic soldiers who lost their lives. We are republishing here an article by Alan Woods, written on the 60th anniversary in 2004, which explains the truth about D-Day: that it was the rapid advance of the Red Army that finally pushed the allies into taking action in France.

6th June marks the 70th anniversary of the Normandy D-Day landings in 1944. Leaders from across the world have gathered to commemorate the heroic soldiers who lost their lives. We are republishing here an article by Alan Woods, written on the 60th anniversary in 2004, which explains the truth about D-Day and the Second World War.

The leaders of the major powers were all present at the official celebrations, a far more pompous celebration than the 50th anniversary. This has more to do with present day politics than the events of 60 years ago. Although it was a brutal and bitter battle, with many soldiers heroically giving their lives, today’s propaganda blows out of all proportion the significance of D-day in terms of the overall development of the war. A far bigger and bloodier war was being fought on the eastern front. It was in fact the speedy advance of the Red Army westwards that finally pushed the allies into opening the front in France in an attempt to stop the Russians from taking the whole of Germany.

Sixty years ago last month, under cover of darkness on a bleak storm-lashed morning, Allied troops landed on the beaches of Normandy. This was D-Day, the long-postponed invasion of Europe. One week after the official ceremonies I visited the Normandy beaches with some friends and comrades. Today the same beaches are placid and tranquil. Strolling on the beaches in glorious June sunshine, it was difficult to imagine the terrible scenes of mayhem and carnage of sixty years ago, when not even half the men succeeded in getting onto Omaha Beach before they were cut down by the murderous fire from German guns.

The story of D-Day has been told many times. It has made a powerful impression on the public through films such as The Longest Day and, more recently, Saving Private Ryan. The recent celebrations, accompanied by a steady stream of television documentaries, have revived the stories about the heroic invasion of France, the terrible cost in human lives, the sacrifice and the bravery. All of this is true. But it does not tell anything like the full story.

The military cemeteries, with their endless lines of crosses, laid out in strict formation, provide no hint of what it was like. The American cemetery is like a beautifully manicured park, with background music from bells that play tunes like The Battle Hymn of the Republic and old men adorned with medals weep for their lost companions and their lost youth.

One curious thing was pointed out to me. The crosses in the American cemetery record only the date of death. There are no dates of birth. Soldiers, it seems, are never born. They only die. That is, in fact, their main function in this life. They die so that others can live in peace and democracy. That is the official legend, at any rate. The truth about war is somewhat different. But on anniversaries such as this, the last thing that is wanted is the truth.

The official celebrations of D-day were like an elaborate piece of theatre. And like all theatre it has to be carefully orchestrated and rehearsed. This year the role of impresario was skilfully played by Jacques Chirac and the French government. As might be expected, they played it with great panache. The villages and towns were all covered with flags of the Allies and placards with slogans such as “Welcome, Liberators” (in English) and “Thank you”. It was all very moving.

Moving, yes, but also a little surprising. This was, after all, the sixtieth anniversary. On the fiftieth anniversary, which is a far more logical time to celebrate, the scene was very different. The celebrations then were on a far smaller scale. The official ceremonies were practically limited to a handful of dignitaries. In fact, many of them were actually cordoned off so as to exclude the public altogether.

What is the difference this time? Clearly more was at stake than a historical memory. It had far more to do with our own times, and the fact that, following the row between Europe and the USA over Iraq, the European governments, and France in the first place, are anxiously trying to mend broken bridges. Stung by American criticisms of “ingratitude”, the French government was trying to prove its sincere commitment to the North Atlantic Alliance. The D-day anniversary was the perfect excuse.

The many former US servicemen who visited France in recent weeks were undoubtedly sincerely moved by the welcome they received from ordinary French people, who in turn were sincere in their desire to pay tribute to the soldiers who risked everything fighting a bloody war against fascism. When ordinary men and women speak of their desire to live in peace and freedom, there is never any doubt about their sincerity. But the words and deeds of ordinary people is one thing, those of the governments and ruling classes are another thing altogether.

Germany’s weakness

The cross-Channel invasion in the summer of 1944 was undoubtedly a massive feat of military planning, involving colossal resources and manpower. The Germans had fortified the coastline with concrete bunkers and artillery – a huge defence system known as the Atlantic Wall. Despite heavy bombardments the German forces retained considerable strength. I was surprised to see that, even today, a number of German bunkers (some with guns still inside) still remain, like grotesque ruined castles, surrounded by deep bomb craters, defying time.

But the history of warfare shows that walls and bunkers are of little use if there are no serious forces to defend them. In 1940, the French felt secure behind the supposedly impregnable defences of the Maginot Line, until the German army swept round them. The German commander Rundstedt complained to close associates that the wall was nothing but a gigantic bluff, a “propaganda wall.” He believed that the invaders had to be hit hard while they were still on the beaches, and driven back into the sea. This required mobile armour, not static defences. Unfortunately, Rundstedt knew his forces were depleted and of generally poor quality:

“Most of the troops left in France were either over-age, or untrained boys, or else Volksdeutschef ethnic Germans from eastern Europe. There were even Soviet prisoners of war -Armenians, Georgians, Cossacks, and other ethnic groups who hated the Russians and wanted to rid their homelands of communism. The weaponry of the coastal divisions was also second-rate, much of it being foreign-made and obsolete.” (M. Veranov, The Third Reich at War, p. 490.)

Alarmed by the prospect of an Allied invasion in France, Hitler dispatched Germany’s most famous general, the legendary Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, former commander of the Afrikakorps, to assess the coastal defences. The German high command expected to benefit from Rommel’s experience and sound technical knowledge, and also hoped that his presence would calm the German public and worry the Allies. But Rommel was shocked by the relative weakness of the German defences and particularly the lack of effective fighting forces.

“Rommel was dismayed by what he found. He was so shocked by the lack of an overall strategic plan that, at first, he dismissed the whole idea of the Atlantic Wall as a figment of Hitler’s imagination, calling it a Wolkenkucksheim, cloud-cuckoo-land. He rated the army troops he saw as no more than barely adequate, and he wrote off the navy and the air force as all but useless. The Luftwaffe could muster no more than 300 serviceable fighter planes to meet the thousands of British and American aircraft that could be expected to cover the skies over the invasion beaches, and the navy had only a handful of ships

“Given the manifest weakness of the German forces, Rommel could see no alternative except to make every effort to stop the invaders at the water’s edge. From his experience in North Africa, he was convinced that Allied fighter planes and bombers would preclude any large-scale movement of German troops hoping to counter-attack against an established beachhead.” (M. Veranov, The Third Reich at War, p. 490.)

The only possibility for the Germans was to halt the invasion on the beaches. As the above lines show, this tactic was determined by weakness, not strength. The Germans concentrated all their best forces for this purpose, with deadly results. Near Saint Laurent, a powerful 88mm anti-tank canon inside a massive protective bunker can still be seen to this day. From this strategic position, with a clear sighting range across the length of Omaha beach, it is easy to imagine the devastating effect of such guns, combined with an incessant hale of machine-gun fire raking the shore, destroying tanks and cutting down soldiers by the score.

Such was the intensity of the German fire that one naval commander prematurely unloaded 29 supposedly amphibious Sherman tanks, too far from the calmer waters near the beach, sending 27 of the tanks straight to the sea-bed with their crews. This left the men of the 116th Regiment without vital tank cover once they were on the beach. On the first day alone, over 2,000 British and American men were killed, wounded or missing.

Despite the heavy losses on the beaches of Normandy, once the British and American forces had landed, the result was a foregone conclusion. The German forces were too weak to offer effective resistance. The reason for this lamentable state of affairs is clear. Hitler had been draining the reserves based in France, in order to make good the heavy losses on the Russian front.

Imperialist intrigues

The Normandy landings were an impressive and costly military operation, but they cannot be compared to the scale of the Red Army’s offensive in the east. This was quite clear to anyone with the slightest knowledge of the conduct of the war, including the Allied commanders and the governments they represented. In August 1942 the US Joint Chiefs of Staff drew up a document that said:

“In World War II, Russia occupies a dominant position and is the decisive factor looking toward the defeat of the Axis in Europe. While in Sicily the forces of Great Britain and the USA are being opposed by 2 German divisions, the Russian front is receiving the attention of approximately 200 German divisions. Whenever the Allies open a second front on the Continent, it will be decidedly a secondary front to that of Russia; theirs will continue to be the main effort. Without Russia in the war, the Axis cannot be defeated in Europe, and the position of the United Nations becomes precarious.” (quoted in V. Sipols, The Road to Great Victory, p. 133.)

These words accurately express the real position that existed at the time of the D-day landings. Yet an entirely different (and false) version of the war is assiduously being cultivated in the media today.

The truth is that the war against Hitler in Europe was fought mainly by the USSR and the Red Army. For most of the war the British and Americans were mere spectators. Following the invasion of the Soviet Union in the Summer of 1941, Moscow repeatedly demanded the opening of a second front against Germany. But Churchill was in no hurry to oblige them. The reason for this was not so much military as political.

The policies and tactics of the British and American ruling class in the Second World War were not at all dictated by a love of democracy or hatred of fascism, as the official propaganda wants us to believe, but by class interests. When Hitler invaded the USSR in 1941, the British ruling class calculated that the Soviet Union would be defeated by Germany, but that in the process Germany would be so enfeebled that it would be possible to step in and kill two birds with one stone. It is likely that the strategists in Washington were thinking on more or less similar lines.

But the plans of both the British and US ruling circles were fundamentally flawed. Instead of being defeated by Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union fought back and inflicted a decisive defeat on Hitler’s armies. The reason for this extraordinary victory can never be admitted by the defenders of capitalism, but it is a self-evident fact. The existence of a nationalised planned economy gave the USSR an enormous advantage in the war. Despite the criminal policies of Stalin, which nearly brought about the collapse of the USSR at the beginning of the war, the Soviet Union was able to swiftly recover and rebuild its industrial and military capacity.

In 1943 alone, the USSR produced 130,000 pieces of artillery, 24,000 tanks and self-propelled guns, 29,900 combat aircraft. The Nazis, with all the huge resources of Europe behind them, also stepped up production, turning out 73,000 pieces of artillery, 10,700 tanks and assault guns and 19,300 combat aircraft. (See V. Sipols, The Road to a Great Victory, p. 132.) These figures speak for themselves. The USSR, by mobilising the immense power of a planned economy, managed to out-produce and outgun the mighty Wehrmacht. That is the secret of its success.

There was another reason for the formidable fighting capacity of the Red Army. Napoleon long ago stressed the decisive importance of morale in warfare. The Soviet working class was fighting to defend what remained of the gains of the October Revolution. Despite the monstrous crimes of Stalin and the Bureaucracy, the nationalized planned economy represented an enormous historic conquest. Compared with the barbarism of fascism – the distilled essence of imperialism and monopoly capitalism, these were things worth fighting and dying for. The working people of the USSR did both on the most appalling scale.

The real turning point of the War was the Soviet counteroffensive in 1942, culminating in the Battle of Stalingrad and later in the even more decisive Battle of Kursk. After a ferocious battle lasting one week, the German resistance collapsed. To the fury of Hitler, who had ordered the Sixth Army to “fight to the death,” General Paulus surrendered to the Soviet army. Even Churchill, that rabid anti-Communist, was compelled to admit that the Red Army had “torn the guts out of the German army” at Stalingrad.

This was a shattering blow to the German army. Though accurate figures are not available, it seems that half of the 250,000 men of the Sixth Army died in combat, or from cold, hunger and disease. About 35,000 reached safety, but of the 90,000 who surrendered, barely 6,000 ever saw Germany again. The Russian victory had cost them about 750,000 men dead, wounded or missing. The cumulative picture was even blacker. In just six months fighting since Mid-November 1942, the Wehrmacht had lost an astonishing 1,250,000 men, 5,000 aircraft, 9,000 tanks and 20,000 pieces of artillery. Over a hundred divisions had either been destroyed or ceased to exist as effective fighting units.

Martin Gilbert writes: “In the first weeks of 1943 the resurgent Red Army seemed to be on the attack everywhere. Operation Star was a massive Soviet advance west of the river Don. On 14 February the Russians captured Kharkov, and further south they were approaching the Dnieper river.” (M. Gilbert, Second World War) Far more than the Normandy landings, the battle of Kursk in July 1943 was the most decisive battle of the Second War. The German army lost over 400 tanks in this epic struggle.

After this shattering blow, the Russian armies began to push the Germans on a long front back towards the west. This was the greatest military offensive in all of history. It immediately caused the alarm bells to ring in London and Washington. The real reason for the Normandy landings was that if the British and Americans had not immediately opened the second front in France, they would have met the Red Army on the Channel.

The reason for the Churchill-Roosevelt conflict

Already at that time, the ruling circles in Britain and the USA were preparing for the coming conflict between the West and the USSR. The real reason why they hastened to open the second front in 1944 was to ensure that the Red Army’s advance was halted. George Marshall expressed the hope that Germany would “facilitate our entry into the country to repel the Russians.” (ibid., p. 135.).

Already at that time, the ruling circles in Britain and the USA were preparing for the coming conflict between the West and the USSR. The real reason why they hastened to open the second front in 1944 was to ensure that the Red Army’s advance was halted. George Marshall expressed the hope that Germany would “facilitate our entry into the country to repel the Russians.” (ibid., p. 135.).

The conflicts between Churchill and Roosevelt on the question of D-day were of a political and not a military character. Churchill wanted to confine the Allies’ war to the Mediterranean, partly with an eye on the Suez Canal and the route to British India, and partly because he was contemplating an invasion of the Balkans to bloc the Red Army’s advance there. In other words, his calculations were based exclusively on the strategic interests of British imperialism and the need to defend the British empire. In addition, Churchill had still not entirely given up the hope that Russia and Germany would exhaust themselves, creating a stalemate in the east.

The interests of US imperialism and British imperialism were entirely contradictory in this respect. Washington, while formally the ally of London, was all the time aiming to use the war to weaken the position of Britain in the world and particularly to break its stranglehold on India and Africa. At the same time it was concerned to halt the advance of the Red Army and gain control over a weakened Europe after the war. That explains the haste of the Americans to open the second front in Europe and Churchill’s lack of enthusiasm for it. Harry Hopkins, Roosevelt’s main diplomatic representative, complained that Churchill’s delaying tactics had “lengthened the timing of the war.”

In August 1943 Churchill and Roosevelt met in Quebec against the background of a powerful Soviet offensive. The Soviet victories at Stalingrad and Kursk forced the British and Americans to act. The remorseless Soviet advance obliged even Churchill to reconsider his position. Reluctantly, Churchill gave in to the insistent demands of the American President. Even so, the opening of the second front was delayed until the Spring of 1944.

All along the conduct of the war by the British and US imperialists was dictated, not by the need to defeat fascism and defend democracy, but by the cynical considerations of great power politics. The divisions between London and Washington arose because the interests of British and US imperialism were different, and even antagonistic. American imperialism did not want Hitler to succeed because that would have created a powerful rival to the USA in Europe. On the other hand, it was in the interests of US imperialism to weaken Britain and its empire, because it aimed to replace Britain as the leading power in the world after the defeat of Germany and Japan.

The decision to open a second front in Italy was dictated mainly by the fear that, following the overthrow of Mussolini in 1943, the Italian Communists would take power. The main aim of the British and Americans was, therefore, to prevent the Italian Communists from taking power. So at a time when the Red Army was taking on the full weight of the Wehrmacht in the battle of Kursk, the British and Americans were wading ashore on the beaches of Sicily. In vain Mussolini pleaded with Hitler to send him reinforcements. All Hitler’s attention was focused on the Russian front.

Churchill’s attention was fixed on the Mediterranean, a position determined by the strategic concerns and interests of British imperialism and its empire. However, from late 1943 it became clear to the Americans that the USSR was winning the war on the eastern front and if nothing was done, the Red Army would just roll through Europe. That is why Roosevelt pressed for the opening of the second front in France. On the other hand, Churchill was constantly arguing for delay. This led to severe frictions between London and Washington. One recent article on the subject states:

“The Normandy landings were long foreshadowed by a considerable amount of political manoeuvring amongst the allies. There was much disagreement about timing, appointments of command, and where exactly the landings were to take place. The opening of a second front had been long postponed (it had been initially mooted in 1942), and had been a particular source of strain between the allies. Stalin had been pressing the Western Allies to launch a ‘second front’ since 1942. Churchill had argued for delay until victory could be assured, preferring to attack Italy and North Africa first.” (http://encyclopedia.thefreedictionary.com/Battle%20of%20Normandy)

The concerns of the imperialists were openly expressed in a meeting of the Joint British and American Chiefs of Staff that took place in Cairo on November 25, 1943. They noted that “the Russian campaign has succeeded beyond all hope and expectations [that is, the hopes of the Russians and the expectations of their “allies”] and their victorious advance continues.” Yet Churchill continued to argue for a postponement of Operation Overlord.

Conflicts with Stalin

The date of the invasion had been fixed for 1 May, but a Note submitted to the meeting stated: “We must not, however, regard ‘Overlord’ on a fixed date as the pivot of our whole strategy on which all else turns. In actual fact, the German strength in France next Spring may, at one end of the scale, be something which makes Overlord Completely impossible.” It would “inevitably paralyse action in other theatres.” (Public Record Office, Prem. 3/136/5, vol. 2, pp. 77-8.)

What “other theatres” are referred to here? The answer was provided in another Note entitled “Entry of Turkey into the War.” It stated that for Turkey to declare war on Germany would spark off hostilities in the Balkans which “would involve the postponement of ‘Overlord’ to a date that might be as late as the 15th of July.” (Public Record Office, Prem. 3/136/5, vol. 2, pp. 106-7.). In other words, Churchill was still concentrating on the Mediterranean and the Balkans. Referring to this, George Marshall told the US Joint Chiefs of Staff that “the British might like to ditch ‘Overlord’ now in order to go into the Balkans.” (John Ehrman, Grand Strategy, vol. V, August 1943-September 1944, p. 117.)

The argument about the second front continued in Teheran, where Stalin met Churchill and Roosevelt on November 28, 1943. The next day, the following exchange took place between Stalin and Churchill:

“Stalin: If possible, it would be good to undertake Operation Overlord during the month of May, say, on the 10th, 15th or 20th.

“Churchill: I cannot give such a commitment.

“Stalin: ‘If Overlord were to be undertaken in August, as Churchill said yesterday, nothing would come out of that operation because of the bad weather during that period. April and May are the most convenient months for Overlord.

“Churchill: […] I do not think that many of the possible operations in the Mediterranean should be neglected as insignificant merely for the sake of avoiding a delay in Overlord for two or three months.

“Stalin: The operations in the Mediterranean Churchill is talking about are really only diversions.” (The Teheran Conference, p. 97.)

That was absolutely correct. The Mediterranean operations were a sideshow compared to the titanic battles on the eastern front. To make matters worse, the British and US forces in Italy, although they had a considerable superiority over the German army, were slowing their advance, allowing the Wehrmacht to move forces from Italy to the Russian front. On November 6, 1943, Molotov had pointed out that the Soviet Union was “displeased by the fact that operations in Italy have been suspended,” allowing for this transfer of troops to the eastern front. “True,” he said, “our forces are gaining ground, but they are doing so at the cost of heavy losses.” (Quoted by Sipols, p. 161.)

The slowness of the Allied advance in Italy was no coincidence. It is now common knowledge that the British and American forces could have taken Rome without having to battle it out for months at Montecassino. They organised a landing at Anzio, further up the coast from Montecassino, and if they had marched quickly towards Rome they could have cut off the German troops who had dug in around the Abbey of Montecassino. Instead they wasted precious time in building their bridgehead on the beach. This allowed the German army to regroup and build a defensive line that basically kept the Allied troops on the beach of Anzio. Once this happened there remained no alternative but to fight their way through the formidable German defence lines at Montecassino. The Allies lost a huge number of soldiers and were bogged down for months as result.

What is evident is that the British and Americans were worried that the partisans could come to power long before the arrival of the Allied forces. Their view was that it was better to let the Nazis fight it out with the partisans and thus weaken the resistance forces. Thus while the Allies were fighting the Germans in Italy, there was an undeclared and tacit agreement between the two sides when it came to stopping the common class enemy, in this case the Italian working class.

However, going back to the question of the second front, it was clear that Roosevelt took a rather different position to Churchill. The Americans had their own reasons for wanting to satisfy the demands of the USSR to open the second front in Europe. They were involved in a bloody war with Japan in the Pacific, where their troops had to capture heavily defended islands, one by one. They realised that, to take on the powerful land armies of Japan on the Asian mainland would be a formidable task, unless the Red Army also launched an offensive against the Japanese in China, Manchuria and Korea. Stalin let it be known that the Red Army would attack the Japanese, but only after the German army had been defeated. This was a weighty reason for Roosevelt to agree to Russia’s demand to launch ‘Overlord’ and overrule the objections of the British.

Fears in London and Washington

The rapid advance of the Red Army in Europe at last forced Churchill to change his mind about Overlord. From a position of supine inactivity in Europe, the Allies hurriedly moved into action. The fear of the Soviet advance was now the main factor in the equations of both London and Washington. So worried were the imperialists that they actually worked out a new plan, Operation Rankin, involving an emergency landing in Germany if it should collapse or surrender. They were determined to get to Berlin before the Red Army. “We should go as far as Berlin […]”, Roosevelt told the Chiefs of Staff on his way to the Cairo meeting. “The Soviets could then take the territory to the east thereof. The United States should have Berlin.” (FRUS, The Conferences at Cairo and Teheran, 1943, p. 254.)

Despite the successes of the Red Army, Hitler still had considerable forces at his disposal. The Wehrmacht remained a formidable fighting machine, with over ten million men, over six and a half million of them in the field. But what is never made clear in the West is that two-thirds of these were concentrated on the Russian front. The only contribution of the British and Americans was the bombing campaigns that devastated German cities like Hamburg and killed a huge number of civilians, but which completely failed either to destroy the Germans’ fighting spirit or halt war production.

Despite the successes of the Red Army, Hitler still had considerable forces at his disposal. The Wehrmacht remained a formidable fighting machine, with over ten million men, over six and a half million of them in the field. But what is never made clear in the West is that two-thirds of these were concentrated on the Russian front. The only contribution of the British and Americans was the bombing campaigns that devastated German cities like Hamburg and killed a huge number of civilians, but which completely failed either to destroy the Germans’ fighting spirit or halt war production.

The German forces on the eastern front had 54,000 guns and mortars, more than 5,000 tanks and assault guns and 3,000 combat aircraft. In spite of the Allied bombing raids, Hitler’s war industries were increasing their production in 1944. They produced 148,200 guns, as against 73,700 in 1943. Production of tanks and assault guns increased from 10,700 to 18,300 and of combat aircraft from 19,300 to 34,100.

The Red Army launched a huge offensive in late December, 1943, which swept all before it. After liberating the Ukraine, they pushed the German forces back through Eastern Europe. The fact is that both Roosevelt and Churchill (not to mention Hitler) had underestimated the Soviet Union. In the event, the Allies met the Red Army, not in Berlin but deep inside Germany. If they had not launched Overlord when they did, they would have met them on the English Channel. That is why the D-Day landings were launched when they were.

The fact is that even after the Normandy landings of June 1944, the eastern front remained the most important front of the war in Europe. The British and US armies got as far as the borders of Germany but were halted there. On the other hand, the advance of the Red Army was the most spectacular in the whole history of warfare. In December 1944, the German High Command decided to launch a counteroffensive in the Ardennes (the “Battle of the Bulge”), with the aim of cutting off the British and US forces in Belgium and Holland from the main Allied forces. The aim of this offensive was more political than military. Hitler hoped to force the British and Americans to sign a separate peace. But the German forces on the western front were too weak to inflict a decisive blow, since most were concentrated on the main theatre of operations in the East. The Wehrmacht advanced some ninety kilometres before being halted.

Churchill wrote to Stalin on January 6, 1945:

“The battle in the West is very heavy and, at any time, large decisions may be called for from the Supreme Command. You know yourself from your own experience how very anxious the position is when a very broad front has to be defended after temporary loss of the initiative. It is General Eisenhower’s great desire and need to know in outline what you plan to do, as this obviously affects all his and our major decisions […] I shall be grateful if you can tell me whether we can count on a major Russian offensive on the Vistula front, or elsewhere, during January […] I regard the matter as urgent.” (Correspondence between the Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the U.S.S.R. and the Presidents of the United States and the Prime Ministers of Great Britain during the Great Patriotic War of 1941-1945, vol. 1, Moscow, 1957, p. 294.)

The Soviet forces did advance on January 12, pushing the German army back on a broad front. The British and US imperialists were placed in a difficult position. On the one hand, as Churchill’s letter shows, they were dependent on the military power of the USSR to defeat Hitler. On the other hand, they were terrified of revolution in Eastern Europe and the rapid advance of the Red Army and the power of the USSR.

Behind the German lines on the Eastern Front, many thousands of Soviet workers and peasants engaged in a heroic and desperate partisan war. On the night of June 19, 1944, more than ten thousand demolition charges laid by Soviet partisans damaged beyond immediate repair the whole German rail network west of Minsk. On the next two nights, a further forty thousand charges blew up the railway lines between Vitebsk and Orsha, and Polotsk and Molodechno. The essential lines for German reinforcements, linking Minsk with Brest-Litovsk and Pinsk, were also attacked, while 140,000 Soviet partisans, west of Vitebsk and south of Polotsk, attacked German military formations.

Martin Gilbert writes: “All this, however, was just the opening prelude to the morning of June 22, when the Red Army opened its summer offensive. Code-named Operation Bagration, after the tsarist General, it began on the third anniversary of Hitler’s invasion of Russia, with a force larger than that of Hitler’s in 1941. In all, 1,700,000 Soviet troops took part, supported by 2,715 tanks, 1,355 self-propelled guns, 24,000 artillery pieces and 2,306 rocket launchers, sustained in the air by six thousand aircraft, and on the ground by 70,000 lorries and up to a hundred supply trains a day. In one week, the two-hundred-mile-long German front was broken, and the Germans driven back towards Bobruisk, Stolbtsy, Minsk and Grodno, their hold on western Russia broken for ever. In one week, 38,000 German troops had been killed and 116,000 taken prisoner. The Germans also lost two thousand tanks, ten thousand heavy guns, and 57,000 vehicles. German Army Group North, on which so much depended, was broken into two segments, one retreating towards the Baltic States, the other towards East Prussia.” (M. Gilbert, Second World War, p. 544.)

Offensive operations on the Western front were renewed in February. In fact, the British and US forces met with little serious resistance, because the great majority of Hitler’s effective fighting forces were fighting on the eastern front. This enabled the British and American forces to advance all along the length of the Rhine. Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe, admitted that they had not encountered any serious opposition.The two US divisions that made the assault suffered only thirty-one casualties. (Dwight D. Eisenhower, Crusade in Europe, New York, 1948, p. 389, my emphasis, AW.)

The fighting spirit of the German army was broken. An average of 10,000 German soldiers surrendered to the British and Americans every day. Yet on the eastern front they continued to fight desperately on. The reason for this must be found in the policies of Stalin. Under Lenin and Trotsky, the Bolsheviks had pursued an internationalist policy. During the bloody Civil War that followed the October revolution, Soviet Russia was invaded by 21 foreign armies of intervention. At one time the Soviet power was reduced to the area around Moscow and Petrograd – little more than the territory of ancient Muscovy. Yet the Revolution succeeded in defeating the imperialists. The reason was that the Bolsheviks carried out internationalist propaganda among the imperialist troops.

As a result, there were mutinies in every one of the interventionist armies. The British prime minister Lloyd George said that the British soldiers had to be withdrawn from Murmansk because they were “infected with Bolshevik propaganda.” By contrast, Stalin pursued a nationalist policy. There was no attempt to win over the ordinary German soldier and to turn them against the Nazi SS. In effect, Stalin’s policy was “the only good German is a dead German.” This ensured that the German army on the eastern front fought to the bitter end, causing terrible casualties in the Soviet army.

The problem for London and Washington was that the Red Army was sweeping through Eastern Europe like an irresistible wave. In only 12 days the Soviet troops moved forward up to 500 kilometres – that is, 25-30 kilometres per day. The German army lost 300,000 killed and 100,000 were taken prisoner. By the time the American and British forces had recovered from the Battle of the Bulge and recommenced their advance on February 8 the Red Army was only 60 kilometres from Berlin, while the British and Americans were still 500 kilometres distant. By the beginning of April the Nazi forces had been driven out of Poland. On April 13 the Soviet forces entered Vienna.

Imperialist manoeuvres

The Nazi leaders knew they had lost the war but a section of them were hoping that the alliance between the USSR and the British and Americans would break down. The idea was to surrender in the west and keep on fighting the Russians in the east. This was not as impossible as it might seem. Negotiations were opened in Switzerland between the chief of American Intelligence in Europe, Allen Dulles, and the representative of the German High Command in Italy, S.S. General Wolff, about a German surrender in Italy.

Upon learning of these negotiations, the Russians insisted on their right to be present in any such negotiations. They were concerned – quite rightly – that the aim of such a surrender would be to transfer German troops from Italy to the eastern front to hold up the advance of the Red Army, thus permitting the British and US forces to advance further eastwards.

Churchill wrote to Stalin with an air of hurt innocence, while Roosevelt assured Stalin of his “truthfulness and reliability”. (Correspondence…, vol. 2, p. 206 and vol. 1, pp. 317-8.) American representatives said that the only contacts they had established with the Germans were to discuss the opening of negotiations. This was a lie. American records reveal that negotiations were already being conducted in Bern. From this it is clear that the aim of the Nazis was indeed to halt the fighting in Italy to transfer troops to the eastern front. (See Bradley F. Smith and Elena Agarossi, Operation Sunrise, The Secret Surrender, Basic Books, New York, 1979.)

In mid-April, the Red Army delivered a crushing blow to the German forces defending Berlin. It had 2.5 million troops, 41,600 guns and mortars, 6,250 tanks and self-propelled guns, and 7,500 combat aircraft. They closed in on Berlin on April 25. Simultaneously, the Soviet and US forces linked up at Torgau on the Elbe, cutting Germany in half.

All this, however, did not mean that the British and American imperialists had not given serious consideration to the possibility of a war against the USSR. In fact, the ruling circles in both London and Washington had considered the possibility, but they realised it was impossible. After fighting a bloody war that was supposed to be a war against fascism, the American and British soldiers would never have been prepared to fight against the Soviet Union. The fears aroused by the economic and military successes of the USSR were expressed in internal memos that were only published years later. A special document was prepared by the US State Department, which stated:

“The outstanding fact [that] has to be noted is the recent phenomenal development of the heretofore latent Russian military and economic strength – a development which seems certain to prove epochal in its bearing on future politico-military international relationships, and which is yet to reach the full scope attainable with Russian resources.” (FRUS, The Conferences at Malta and Yalta, 1945, pp. 107-8.)

These lines startlingly reveal the real calculations of the imperialists. At the height of the War, the British and US ruling circles were already sizing up the situation in Europe and preparing for a struggle against their Russian allies. The Americans considered the possibility of a war against the Soviet Union even before Hitler was defeated, and ruled it out – only because they correctly though that they could not win.

The report pointed out that the USSR’s military and industrial strength was already greater than that of Britain. Even if the USA joined forces with Britain against the USSR, the report concluded, with amazing frankness, they “could not, under existing conditions, defeat Russia.” The State Department concluded that in such a conflict the USA “would find itself engaged in a war which it could not win.” (ibid., my emphasis, AW)

Collapse of Nazi regime

The German bourgeoisie paid a heavy price for handing power to Hitler and his fascist gangsters. Once in power, the Nazi bureaucracy could not be controlled by the ruling class. They were guided by their own interests, which did not necessarily coincide with those of the bourgeoisie. As long as Hitler protected them against Bolshevism, the German capitalists were happy to back him. As long as Hitler’s armies were advancing, they joined in the applause and fascist salutes. But when they saw that Germany was losing the war, their attitude changed.

Even before this, the bourgeoisie would have ended the war and sought to reach an agreement with the British and Americans. Unfortunately for the German bankers and industrialists, it was not possible to influence Hitler or remove him from office by constitutional means. Therefore they resorted to conspiracies with a section of the general staff. An attempt to kill Hitler in July 1944 failed and a savage purge ensued in which thousands were arrested and murdered. Colonel Graf Klaus von Stauffenberg, the chief conspirator, was shot. Rommel, the hero of the Africa campaign who was also implicated, was ordered to take poison. Other officers were not so lucky. Eight of them were hanged with piano wire – an unambiguous message from the Gestapo to any other officers with doubts about the Fuehrer. Having liquidated the bourgeois opposition and terrorised the General Staff, Hitler and his clique were now more determined than ever to fight to the bitter end, irrespective of the consequences for Germany and the bourgeoisie.

The Nazi regime was now in a state of total disintegration. Some of the Nazi leaders were still hoping for a split between the USSR and the British and Americans. They were trying up to the last minute to come to terms with the latter. One such attempt was made by Himmler through the Swedish government, but it came to nothing. When Hitler found out about it he was furious. According to eyewitness accounts, he raged like a madman, his face turned bright red and he was almost unrecognisable.

Lord Acton wrote: “Power tends to corrupt. Absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Hitler was completely out of touch with reality, and this unhinged his mind. In the end he was obviously insane. He ordered the complete destruction of the Ruhr, Germany’s industrial heartland, to stop it falling into enemy hands: He ordered that “all industrial and food-supply installations within the Reich, which could be of any immediate or future use to the enemy for the continuation of his fight, will be demolished.” (Milton Shulman, Defeat in the West, p. 283.)

“Hold on till the end”, Hitler ordered. But by this time, Hitler’s hold on his state and army was slipping. The Ruhr was not destroyed. General Friedrich Koechlin, the commander of the 81st Corps, later wrote: “The continuation of resistance in the Ruhr was a crime.” (ibid., p. 284.) On April 16, 80,000 German soldiers gave themselves up to the Allies. Two days later, 325,000 troops, including thirty generals, crawled out of their holes to surrender.

Almost to the end, Hitler continued to issue orders to non-existent troops, and to move imaginary planes and divisions. But the Twilight of the Gods had arrived. He committed suicide on April 30th and his body was soaked with petrol and burnt – a fittingly sordid end for a fascist monster. As his corpse went up in flames the sound of Russian guns was heard in the heart of Berlin. On May 1, the Soviet flag was hoisted over the Reichstag. The following day the Soviet forces were in complete control of the German capital.

Once it became clear that a deal with Britain and America was impossible, what remained of the Nazi leaders’ will to fight on collapsed. Five days later, Germany surrendered.

Counterrevolutionary policy

As it became clear that the Soviet Union would emerge as the dominant force in Europe after the War, Churchill’s reactionary tendencies, which he had been compelled to dissimulate, came to the surface. For this counterrevolutionary gangster, the main enemy was no longer Nazi Germany. It was the Soviet Union. The Red Army had smashed the armies of Hitler in East Prussia and was on the point of entering Berlin. Churchill wrote to the Soviet Government that the Red Army’s achievements deserved “unstinted applause” and future generations acknowledge their debt to them “as unreservedly as do we who have lived to witness these proud achievements.” (Correspondence…, Vol. 1, pp. 305-6.)

But these words reeked of hypocrisy. In reality, Churchill was not at all pleased at the Russian advance. The American general Eisenhower planned to encircle and destroy the German forces defending the Ruhr, and then divide the enemy forces by linking up with the Soviet army. But this plan was vehemently opposed by Churchill, who wanted at all costs to keep the Russians out of Berlin. He wanted the British and Americans to take Berlin, not the Red Army. He wrote a cable to Roosevelt on April 1: “I therefore consider that from a political standpoint we should march as far east into Germany as possible, and that should Berlin be in our grasp, we should certainly take it.” (Roosevelt and Churchill, Their Secret Wartime Correspondence, p.669.)

The British Prime Minister wrote in his memoirs that the destruction of Germany’s military power “had brought with it a fundamental change in the relations between Communist Russia and the Western democracies. They had lost their common enemy, which was almost their sole bond of union.” Outlining his strategy, Churchill advocated the creation of a front to halt the advance of the Red Army. This front had to be as far to the east as possible. Berlin was the main objective. The Americans should enter Prague and occupy Czechoslovakia. And a settlement should be reached on all major issues between the West and the East in Europe before the British and Americans “yielded any part of the German territories they had conquered.” (Winston Churchill, The Second World War, vol. VI, p. 400.)

Throughout the War, the genuine interests of the peoples of occupied Europe were not the main motivating force of the ruling circles in London and Washington. All their actions were merely an expression of the crudest big power politics. And fear of revolution was never very far away. Thus, it was decided that Germany should be disarmed, but that she should be allowed to retain “such forces as were required for the maintenance of public order.” These gentlemen remembered only too well the revolutionary wave that swept through Germany after the end of the First World War.

Churchill feared a revolution in Germany after the collapse of the Nazi regime. He later admitted that he had instructed Field Marshall Montgomery in late April “to be careful in collecting the German arms, to stack them so that they could easily be issued again to the German soldiers,” if London thought it necessary. (See The Daily Herald, November 24, 1954). This was exactly the same policy pursued by the British at the end of the First World War, when they allowed the German army to keep thousands of machine-guns, in violation of the Versailles Treaty, to put down the German Revolution.

Even while the war with Nazi Germany was still raging, the Allies were preparing to put down uprisings of the masses and prop up right wing regimes, like the regime of Badoglio in Italy. The American historian D.F. Fleming points out: “We sought to preserve the power of the top social strata which had long ruled these countries.” (D.F. Fleming, The Cold War and its Origins, 1917-1960, Vol. 1, p. 210.)

In January 1945 the US State Department proposed the setting up of a Provisional Security Council for Europe or Emergency High Commission to “achieve unity of policy and joint action” in Europe. The purpose of this body was to set up provisional governments in Europe after the defeat of the Nazis and “the maintenance of order” – that is, the suppression of revolutions. The authors of the document stressed that “every possible effort” must be made “to induce the Soviet Government to agree.”

The imperialists were terrified that the entry of the Red Army into Eastern Europe, and the overthrow of the Nazi puppet regimes, would be the signal for revolt. These fears were well founded. The spectacular advance of the Red Army and the collapse of the Nazi regimes in Eastern Europe produced a revolutionary wave both in Eastern and Western Europe. However, contrary to the belief of Churchill, Stalin had no interest in seeing workers’ revolutions in Europe, because of the effect this would have on the workers of the USSR.

As an indication of his “good intentions”, Stalin ordered the dissolution of the Communist International (Comintern), which was set up by Lenin and Trotsky in 1919 to further the cause of world revolution. The Comintern was wound up ignominiously, without even the pretence of a congress, on May 15 1943. This was Stalin’s signal to the British and American imperialists that they had nothing to fear from him – at least as far as world revolution was concerned:

A Stalinist author writes: “Replying on May 28 to the question of Harold King, Moscow correspondent of Reuters, as to the effect the dissolution of the Comintern would have on the future of international relations, Stalin wrote that the dissolution of the Communist International facilitated the organization of a common onslaught of the United Nations against the common enemy. The Comintern’s dissolution exposed the Nazi lie that ‘Moscow’ intended to intervene in the affairs of other nations and to ‘Bolshevise’ them.” (V. Sipols, p. 142.)

In 1944 the British imperialists intervened militarily in Greece to crush the partisans who were led by the Communist Party. This was a direct result of the policies of Stalin, who had done a deal with Churchill to carve up the Balkans and Eastern Europe into Russian and British spheres of influence. This is not the place to deal with the diplomatic horse-trading that went on between Russia, the USA and Britain during the war, but it is quite clear that all three powers were jockeying for positions after the defeat of Nazi Germany. Stalin had attempted to come to an accommodation with the imperialist powers between 1944 and 1945 at the Big Three Conferences at Teheran, Moscow, Yalta and Potsdam. Churchill noted down his conversation with Stalin in October 1944:

“The moment was apt for business, so I said, ‘Let us settle about our affairs in the Balkans. Your armies are in Romania and Bulgaria. We have interests, missions, and agents there. Don’t let us get at cross-purposes in small ways. So far as Britain and Russia are concerned, how would it do for you to have 90 per cent predominance in Romania, for us to have 90 per cent of the say in Greece, and go 50-50 about Yugoslavia?’ While this was being translated I wrote out on a half sheet of paper:

Romania: Russia 90 per cent; The others 10 per cent

Greece: Great Britain (in accord with USA) 90 per cent; Russia 10 per cent

Yugoslavia: 50-50 per cent

Hungary: 50-50 per cent

Bulgaria: Russia 75 per cent; The others 25 per cent“I pushed this across to Stalin, who had by then heard the translation. There was a slight pause. Then he took his blue pencil and made a large tick upon it, and passed it back to us. It was all settled in no more time than it takes to set down. After this there was a long silence. The pencilled paper lay in the centre of the table. At length I said, ‘might it not be thought rather cynical if it seemed we had disposed of these issues, so fateful to millions of people, in such an off-hand manner? Let us burn the paper.’ ‘No, you keep it’ said Stalin.” (W. Churchill, Triumph and Tragedy, pp. 227-8.)

The actions of Stalin gave the green light to Churchill to crush the revolution in Greece. In Greece the British army smashed the partisans of EAM, who had led the struggle against the Nazi occupation, in order to give power to the king and his reactionary clique. This led to a bloody civil war and a reactionary government in Greece that lasted for decades.

Counterrevolution in a democratic form

Plans for the carve-up of post-war Europe had already begun well before the invasion of France. The US army was supposed to occupy Germany from the Swiss frontier to Düsseldorf, while the British were to occupy the territory from Luebeck to the Ruhr. The Americans intended to control France and Belgium, and the British aimed to control Holland, Denmark and Norway. The situation in Eastern Europe was more difficult, because of the presence of the Red Army. But there too Churchill was manoeuvring with so-called governments of exile.

As early as 1943 the British Foreign Office had begun to work out plans for putting down revolutionary movements in liberated Europe. The intention of the British and Americans was to impose on the liberated populations of Europe the rule of so-called governments in exile that were really only right wing bourgeois cliques without any base, who had been sitting in London for the duration of the War, like the “government in exile” of Charles de Gaulle. The so-called “Gaullist Resistance” was not nearly as significant as French bourgeois historians claim it was. It cannot be compared with the real French Resistance, which, as in every other country, was led by the Communists. The latter were actually responsible for the liberation of Paris. De Gaulle was shipped back to France by the British and sent to make pompous speeches in Bayeux and other liberated cities, although his actual role in the fighting – like his “mass base” of support in France – was non-existent.

On August 18th a general strike broke out. Factories were occupied by the workers. On the 19th, the police went on strike and seized control of the Prefecture. Under the leadership of Colonel Rol-Tanguy, the former leader of CGT Metalworkers Union, the Communist Resistance passed over to an all-out offensive. The movement, involving 100,000 insurgents from the outset, was so widespread that the Germans could do nothing. A counter-offensive was considered, but then cancelled. The German commander, General von Choltitz, entered into secret negotiations with the Resistance through the medium of the Swedish Legation.

A truce was agreed on, in which important parts of Paris were handed over to the Resistance and the Germans agreed to treat all Maquis fighters as soldiers. But the ceasefire broke down almost immediately and the street fighting recommenced. Barricades were set up all over Paris. It was a complete insurrection. The demoralized German forces could put up only relatively mild resistance. The officers locked themselves up in hotels and barracks for safety and waited for the Allies to save them from the anger of the masses. After five days of fighting, Paris had fallen – to a revolutionary insurrection.

De Gaulle, personally, and the British and Americans troops played absolutely no role in the liberation of Paris. Originally, the Allied armies moving inland from Normandy did not even intend to enter Paris, but to skirt around it to the South. Only the pressure of de Gaulle made them change their plans. He was anxious to enter Paris as soon as possible, not out of any concern for the sufferings of the people of Paris, but to prevent a repeat of the Paris Commune of 1871, but now under the infinitely more favourable conditions from a revolutionary point of view.

On the day the communist-led insurrection broke out, the Second Armoured Division under Gaullist command was still 200 kilometres away from Paris. A small number of tanks were rushed ahead to the capital, in order to allow the Gaullist forces to claim at least some part in the uprising, but did not arrive until the 24th, by which time the German forces were already defeated. When de Gaulle finally entered Paris on the 26th, he was horrified to discover that Rol-Tanguy had accepted and signed the official surrender of General von Choltitz on the previous day.

A revolutionary wave swept through France and the whole of Europe. But it was betrayed by the combined efforts of the leaders of the Social Democracy and Stalinism. In Italy and Greece, as in France, the Resistance was controlled by the Communist Parties. They could have taken power after the War but were prevented by Stalin, who feared revolution like the plague. Instead, he instructed the Communists of France and Italy to join Popular Front governments, from which they were later ejected. As a result, in Western Europe, we had counterrevolution with a democratic face.

When Mussolini was overthrown in June 1943, the Allies hastily recognised the government of the fascist marshal Badoglio, who changed sides and even declared war on Germany. But in reality Badoglio’s government was hanging in mid air. Power was in the hands of the Italian workers and the partisans who were led by the Communist Party. Not by accident, the first act of the RAF was to bomb hell out of the northern cities in order to terrify the masses and as a warning to the partisans.

But by 1945 the real power in Italy was, in reality, in the hands of the Communist Party and the partisans. They captured and executed the hated fascist dictator Mussolini, who ended his days suitably hanging from a petrol pump together with his mistress. Communist partisans liberated Milan on April 25, just as they had earlier liberated Paris. The workers seized the factories. The road to a socialist revolution in Italy was open. Yet Togliatti and the other leaders of the PCI, following orders from Moscow, held the workers back from taking power. Instead, they advocated entering a coalition with the Christian Democrats. The policies of the Stalinists effectively derailed the revolution and handed power back to the reactionary circles backed by London and Washington.

The counterrevolutionary policies of the so-called “Western democracies” included collusion with Nazis and other right wing forces in Europe. By this time their main objective was to combat “Communism”. Churchill was the main moving force in this counterrevolutionary activity, but he was backed (albeit more cautiously) by Washington. In order to prevent revolution, Churchill backed the monarchists in Italy as a bulwark of reaction. It is well known that the British and Americans helped many Nazi war criminals to escape from Italy to South America with the enthusiastic aid of the Vatican. Others went to the United States where they played an active role assisting the CIA in the Cold War.

Matters in Eastern Europe were very different. With the advance of the Red Army, the old state power collapsed. The ruling class had collaborated with the Nazis and fled before the advancing Soviet forces. Again, the working class could have taken power, but they were held back by the Stalinists, who took their orders from Moscow. Coalition governments were set up in which the Communists were in a minority. But they always held two ministries: defence and interior – the army and the police. In addition, the Red Army was present as an insurance policy.

Trotsky once said that to kill a tiger one requires a shotgun but to kill a flea, a thumbnail is sufficient. The Stalinists liquidated capitalism in Eastern Europe but they did not introduce socialism. These regimes began where the Russian revolution ended – as bureaucratically deformed workers’ states. The expropriation of the capitalists and landlords was undoubtedly a progressive task, but it was carried out bureaucratically, from above, without the democratic participation and control of the working class.

The regimes that emerged from this were a bureaucratic and totalitarian caricature of socialism. Unlike the Russian workers’ state established by the Bolsheviks in 1917, they offered no attraction to the workers of Western Europe. With the exception of Czechoslovakia, the bourgeoisie of Eastern Europe had been very weak before the War. The US imperialists attempted to strengthen the bourgeois elements and gain control of Eastern Europe by offering them Marshall Aid. Stalin understood the manoeuvre and gave the order. The Stalinists took power by expelling the bourgeois elements from the coalitions and nationalising the means of production.

Origins of the Cold War

President Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945 and was replaced by Vice President Truman. Many people have assumed that Roosevelt was less anti-Communist than his successor. But this is not the case. The reason why Roosevelt did not want an immediate clash with Moscow was that it did not suit the interests of American imperialism to break with Moscow at that point in time. In addition to the considerations already mentioned, the Americans had another reason for not sharing Churchill’s enthusiasm for a “crusade against Bolshevism” – or, at least, the timing. The Americans’ main preoccupation was the war in the Pacific, where they were still locked in a life-or-death struggle with Japanese imperialism.

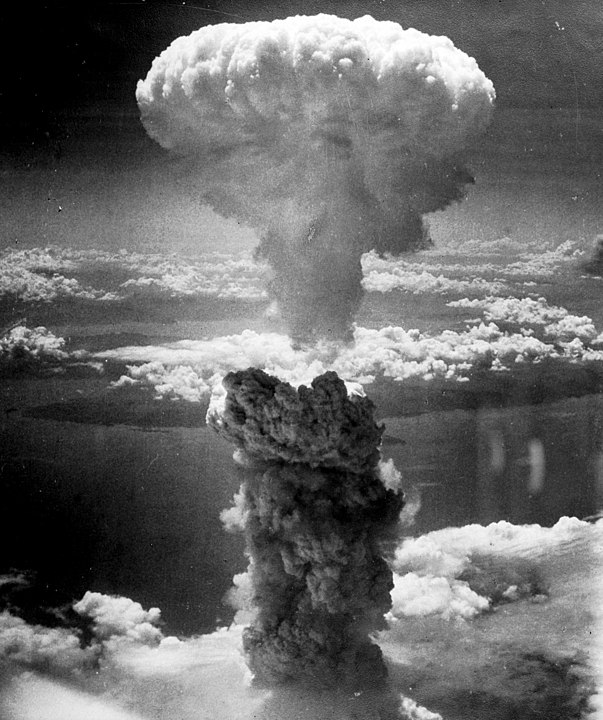

The problem was that the USSR had a huge army in the heart of Europe. Only the possession of nuclear weapons gave the USA a potential advantage, since the USSR did not yet have the atom bomb. But the bomb had not yet been tested, and there was no guarantee that it would work. The Americans tested the first atom bomb on June 16, 1945, at the very time the wartime Allies were meeting in Berlin to discuss the post-war situation. Truman and Churchill were informed that the test had been successful and wasted no time in letting Stalin know all about it. They hoped to use the threat of nuclear devastation to tip the balance of the negotiations in their favour.

Some have maintained that the Cold War did not begin until 1947, but in fact it began immediately after the surrender of Japan, and was prepared even before that. D.F. Fleming states: “that President Truman was ready to begin it before he had been in office two weeks.” (D.F. Fleming, The Cold War and its Origins, 1917-1960, Vol. 1, p. 268.) The possession of the atom bomb gave Truman a sense of superiority, which he did not feel the need to hide. James F. Burns, director of the US war mobilisation department, assured Truman that possession of the atom bomb would put the USA in a position “to dictate our own terms at the end of the war.” (Harry S. Truman, Memoirs, vol. I, Year of Destiny, New York, p. 87.)

As usual, Churchill was the first to foment an anti-Communist crusade. This rabid reactionary and warmonger was doing everything in his power to push the Americans into a conflict with Russia. Describing his mood at this time, General Allen Brooke, the Chief of the British Imperial General Staff, noted in his diary that “he was always seeing himself capable of eliminating all the Russian centres of industry and population […]” (Arthur Bryant, Triumph in the West, 1943-1946, London, 1959. p. 478.) But the British working class had had enough of Churchill. They had had enough of war too, and certainly had no desire to engage in a new war, least of all against the Soviet Union. In the 1945 general election they kicked Churchill and the Conservatives out of power and voted massively for a Labour government.

In any case, Britain was already reduced to the role of a secondary power, a mere satellite of the USA – a role that has continued to the present-day. The Americans did not pay much attention to Churchill’s raving because they still had unfinished business in the Pacific. They needed the help of the Soviet Union to defeat Japan, and therefore were not in a hurry to bring about a premature confrontation with the Russians in Europe. That could wait until Japan had surrendered.

The defeat of Japan

The Japanese had a powerful land army in Manchuria, the Kwantung army. Its total strength was up to a million men. It had 1,215 tanks, 6,640 guns and mortars and 1,907 combat aircraft. This formidable fighting force was faced by 1,185,000 Soviet troops stationed in the Soviet Far East. These were reinforced with additional forces after the surrender of Germany and when the offensive began on August 9 totalled 1,747,000 troops, 5,250 tanks and self-propelled guns, 29,835 guns and mortars and 5,171 combat aircraft. In a campaign lasting just six days the Red Army smashed the Japanese forces and advanced through Manchuria with lightning speed. The Soviet forces entered Korea and the South Sakhalin and Kurile Islands and were in striking distance of Japan itself.

The Japanese had a powerful land army in Manchuria, the Kwantung army. Its total strength was up to a million men. It had 1,215 tanks, 6,640 guns and mortars and 1,907 combat aircraft. This formidable fighting force was faced by 1,185,000 Soviet troops stationed in the Soviet Far East. These were reinforced with additional forces after the surrender of Germany and when the offensive began on August 9 totalled 1,747,000 troops, 5,250 tanks and self-propelled guns, 29,835 guns and mortars and 5,171 combat aircraft. In a campaign lasting just six days the Red Army smashed the Japanese forces and advanced through Manchuria with lightning speed. The Soviet forces entered Korea and the South Sakhalin and Kurile Islands and were in striking distance of Japan itself.

On August 6, the Americans had dropped an atom bomb on Hiroshima. Three days later, the very day the Soviet army began its offensive, they dropped a second bomb on Nagasaki. They did this despite the fact that these were civilian cities with no military value and the Japanese were already defeated and suing for peace. The fact is that these atom bombs were intended as a warning to the USSR not to continue the Red Army’s advance, otherwise they could have occupied Japan. The use of the atom bomb was a political act. It was intended to show Stalin that the USA now possessed a terrible new weapon of mass destruction and was prepared to use it against civilian populations. There was an implicit threat: what we have done to Hiroshima and Nagasaki we can do to Moscow and Leningrad.

Once Japan had surrendered, Washington’s attitude to Moscow changed immediately. The whole shape of the post-war world was now determined. The world would be dominated by two great giants: mighty US imperialism on the one hand and mighty Russian Stalinism on the other. They represented two fundamentally opposed socio-economic systems with antagonistic interests. A titanic struggle between them was inevitable.

The American imperialists now felt themselves masters of the world. They had suffered relatively little from the war. Their productive base was intact, whereas most of Europe’s industry lay in a heap of smouldering rubble. Two thirds of all the available gold in the world was in Fort Knox. The USA had a huge army and a monopoly of nuclear weapons. They could impose their conditions on the rest of the world. Only the Soviet Union stood in their way. The arrogance of American power was put into words by the managing director of The New York Times Neil MacNeil, who wrote that “both the United States and the world need peace based on American principles – a Pax Americana […] We should accept an American peace. We should accept nothing less.” (Neil MacNeil, An American Peace, New York, 1944, p. 264.)

Postscript: the end of a myth

Last month’s celebrations around the 60th anniversary of D-day were designed to perpetuate a myth. The Normandy landings did not end the Second World War in Europe, which was fought and won on the eastern front.

To say this is not to belittle the courage of the British and American troops. The soldiers who had to endure the Normandy landings went through hell. According to figures issued by Supreme Headquarters, Allied casualties in the first 15 days of battle totalled 40,549. The British lost 1,842 killed, 8,599 wounded, and 3,131 missing. The Americans lost 3,082 killed, 13,121 wounded, and 7,959 missing. The Canadians lost 363 killed, 1,359 wounded and 1,093 missing. This was bad enough Yet it does not bear comparison with the appalling losses suffered on the eastern front. (See Martin Gilbert, Second World War, p. 536.)

All the peoples paid a terrible price for the War. Britain’s casualties totalled 370,000, the USA, 300,000.But the Soviet Union lost a staggering 27 millions – about half of all the casualties of the Second World War. According to one estimate, even before the Normandy landings, 90 percent of all young men between the age of 18 and 21 in the Soviet Union had already been killed. These chilling figures accurately express the real situation. They show that the people of the Soviet Union suffered a disproportionate number of casualties, because the main front in Europe was the eastern front.

In addition to the terrible loss of life, the productive base of the Soviet Union was severely damaged by the depredations of Hitler’s hordes, who bombed, burned and looted, causing the wholesale destructio

n of industry in the occupied territories of the USSR. Yet after the war, the USSR rebuilt its economy in a very short space of time. The superiority of a nationalized planned economy, which was already demonstrated by the War itself, was confirmed in the period of post-war reconstruction, when it achieved a regular rate of growth of 10 percent per annum.

Western historians, motivated rather by political considerations than historical truth, have systematically minimised the role of the Soviet Union in the Second World War. This systematic campaign of distortion has increased a hundred-fold since the fall of the Berlin Wall. The defenders of capitalism are not willing to acknowledge the achievements of the nationalized planned economy in the USSR. They cannot admit that the spectacula

r military victory over Hitler Germany was due precisely to this.

In order to belittle the role of the USSR in the war, they exaggerate the importance of things like American Lease-Lend to the Soviet Union. This falsification is easy to answer. The fact is that the Red Army had halted the German advance and begun to counterattack by the end of 1941 in the Battle of Moscow – before any supplies had reached the USSR from the USA, Britain or Canada.

These supplies came mainly in the period 1943-5, that is, at a period when the Soviet economy was already producing more military hardware than the German war machine. They accounted only for a fraction of Soviet war production: two percent of artillery, ten percent of tanks and twelve percent of aircraft. In no sense can this be considered decisive to the Soviet war effort as a whole. Its importance was marginal.

The real reasons for the marvellous achievements of the Soviet Union in the Second World War was something the Western historians are never prepared to admit – firstly, the superiority of a nationalised economy and central planning, and secondly, the determination of the Soviet working class to defend what remained of the conquests of the October Revolution against fascism and imperialism.

This was no thanks to Stalin and the bureaucracy, who had placed the USSR in extreme danger by their criminal and irresponsible policy before the War, but in spite of them. The Soviet workers, despite all the crimes of Stalin and the bureaucracy, rallied to the defence of the USSR and fought like tigers. This was what ultimately guaranteed victory.

As a matter of fact, the capitalist regimes in Britain and the USA, in an indirect way, admitted the superiority over central planning over market anarchy during the war. When matters were really serious and their backs were against the wall, how did they react? Did they say, as they do nowadays, that everything should be left in private hands? Did they sing hymns to the glories of market economics and private enterprise? They did not!

They introduced emergency legislation to centralise production, especially of the war industries. They introduced measures of planning, the direction of labour, rationing and so on. Why did they do this? For one very good reason: because these methods gave better results. So much for the argument about the alleged superiority of the “free market economy”!

Of course, this was not socialism. The basic levers of the economy remained in the hands of private capitalists. Real planning is not possible under capitalism. And the nationalized industries were run by bureaucrats. But despite these limitations, even these elements of a planned economy gave serious results for a time. The elements of planning, even on a capitalist basis, gave better results than the free-for-all of the market economy. Just imagine the results that would be possible in a real socialist planned economy in which the benefits of a central plan would be combined with the democratic control and administration of the working people themselves.

After 1945 the United Nations was set up, supposedly to guarantee world peace. But today, six decades after D-Day, the world is anything but a peaceful place. One war succeeds another in one country after another, in one continent after another. In the modern epoch wars are the expression of the unbearable contradictions that flow from the capitalist system itself. The entire world is dominated by a handful of super-rich nations, which in turn are dominated by a handful of super-rich and powerful corporations and banks. The actions of these are determined – as they were always determined – by the greed for rent, interest and profit, for markets, raw materials and spheres of influence.

In the Second World War, fifty-five million men, women and children perished. Millions more will perish in the coming years and decades, not just in wars and other military conflicts, but from starvation and epidemics like malaria, AIDS and simple diseases caused by the lack of clean drinking water.

The worst thing about all this is that it is objectively unnecessary. In the first decade of the 21st century, when science and technology have performed unheard-of miracles, the majority of the human race faces a grinding struggle to survive. The gap between rich and poor has widened into an abysm, and at the same time the gap between the so-called rich and poor nations has never been greater.

These facts lie behind the tensions and antagonisms that create wars, ethnic strife, terrorism, and all the other horrors that afflict our tortured and turbulent planet. As long as these central contradictions are not resolved, wars and other violent conflicts will continue to sow death and destruction. It is useless to bemoan the results of war, as moralists and pacifists do. It is necessary to diagnose the source of the illness and prescribe a cure.

The enormous potential of a nationalised planned economy was demonstrated by the Soviet Union, before, during and in the first 25 years after the Second World War. Despite all the efforts of the bourgeoisie and its hired prostitutes to deny it, the fact is that the USSR (and later China) showed that it is possible to run an economy without private capitalists, bankers, speculators and landlords, and that such an economy can obtain spectacular results.

Ah, but the Soviet Union collapsed. Yes, the Soviet Union collapsed after decades of bureaucratic and totalitarian rule, which completely negated the regime of workers’ democracy established in 1917. As early as 1936, Leon Trotsky predicted that the Stalinist Bureaucracy that usurped power after Lenin’s death, would not be satisfied with its legal and illegal privileges, but would inevitably strive to replace the nationalised planned economy by privately owned monopolies.

The capitalist counterrevolution in Russia, however, offers no way forward to the peoples of the former USSR. It has been accompanied by a horrific collapse of the Russian economy, living standards and culture, as Trotsky predicted. If there is a country in the world where capitalism stands condemned, that country is Russia.

The prolongation of senile capitalism threatens the future of human culture, civilization, democracy, perhaps even the survival of humanity itself. The world is crying out for a fundamental social and economic transformation. The only hope for humanity consists in the radical abolition of capitalism and the establishment of a harmonious system of production and distribution based on the common ownership of the means of production under democratic workers’ control and administration.

The future socialist planned economy will not be based on backwardness, as was the regime established by the Bolshevik Party of Lenin and Trotsky in November 1917. It will draw on the colossal advances of industry, science and technology, which will become the servants of human needs, not the salves of the profit motive.

On the basis of a modern, technologically advanced economy, rational planning will spur production to an unprecedented level. It will be possible in a relatively short time to abolish hunger, homelessness, misery and illiteracy and all the other elements of barbarism that make life a hell on earth for countless millions of people. In place of the old strife and rivalry between nations it will be possible to unite the productive forces of the whole planet in a socialist commonwealth, where wars will be consigned, along with slavery, feudalism and cannibalism, to a museum of barbarous relics of the past.