This week’s planned protests in Cuba ended in failure, with the forces of reaction unable to mobilise ordinary people to their cause. On the other side, young communists are beginning to organise in defence of the Cuban Revolution.

In the end, the much anticipated opposition demonstration of 15N in Cuba did not materialise. The organisers’ ties with Washington and with counter-revolutionary and terrorist elements removed any legitimacy from their call to mobilise.

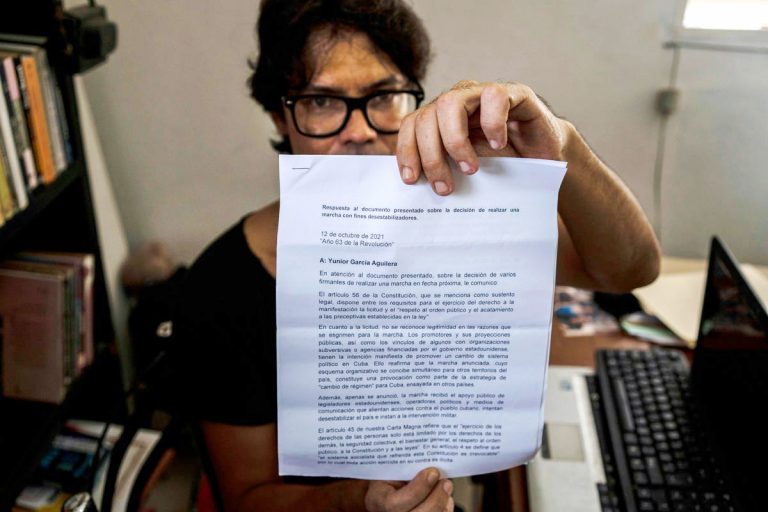

Selective police repression did the rest. After calling off the demonstration, playwright Yunior García, the public face of 15N, ended up leaving for Madrid. But perhaps the most significant development in these few days – about which the Western capitalist media has been silent – has been the rise of the red scarf movement.

Imperialist hypocrisy

The total failure of N15 has dealt a severe blow to all those who were expecting and had prepared the ground for large anti-government demonstrations, police repression and regime change.

The US had issued stern warnings of more sanctions should the Cuban government carry out a crackdown, in the typical double standards of imperialism, which turns a blind eye to brutal repression of peaceful demonstrators and police killings in its own country.

European Union MEPs tried to land on the island shouting, “we want the same for Cuba that we have in Europe”. They were referring to so-called ‘human rights’ – rights about which the Polish police in the same capitalist EU show a very different regard for when they deploy tear gas, barbed wire, and water cannons against refugees at their border seeking asylum and humanitarian protection.

But all of them had made a serious mistake: they had underestimated the deep rooted anti-imperialist sentiment and instincts of the Cuban people.

On 11 July, a few thousand came out to protest in various cities on the island. Their motivations were varied.

Many came out to protest against deteriorating living conditions and the daily hardships that they suffer. The US blockade (which Trump tightened substantially and Biden has left intact) is above all responsible for this deterioration, which has been severely aggravated by the pandemic (which eliminated vital tourist income), and worsened by the Ordenamiento package of measures applied by the government since 1 January.

Added to all this are the chronic problems caused by the bureaucratic mismanagement of the planned economy and the negative impact of the measures of opening up to the capitalist market.

Among those who came out to protest against the government on J11 there was also a layer of young people unhappy with the state’s arbitrariness, censorship, and stifling bureaucratism.

Finally, openly counter-revolutionary and annexationist layers were also present. By virtue of the fact that they were the only participants who were really organised and in possession of clear ideas and a programme, it was the latter who dominated the protests politically.

This drawing together of distinct sources of discontent, however, was not repeated ahead of 15 November.

The organisers, the so-called ‘Archipelago platform’, made their call exclusively in relation to the democratic rights of those jailed and indicted as a result of the J11 protests. The organisers made no reference to the state of economic hardship, and no attempt to connect with the sectors hardest hit by the economic crisis, some of whom had come out to express their frustration on J11.

Worse than that, while Archipelago tried to frame their call in terms of “non-violence in the face of state repression”, of “dialogue and consensus in the face of imposition”, in reality many of those who came out to publicly support the call were openly counter-revolutionary elements and even terrorists.

Neither Yunior García nor Archipélago ever distanced themselves from such elements. On the contrary, their entire strategy was based on creating the broadest unity of action against the Cuban government.

In practice, their argument about being “neither of the right, nor of the center, nor of the left” as usual turned out to mean, “a united front with the most repulsive reactionary layers against the revolution”.

Kiss of death

What ended up deflating the call for a march on N15 were Yunior García’s proven links with Washington’s multimillionaire efforts to provoke a ‘transition’ in Cuba – i.e. regime change and the restoration of capitalism, a plan that also has a clear annexationist component.

The Cuban people have many criticisms about the situation they are facing, rightly so, and many of them are directed, justifiably, at the government and the state.

These criticisms are not the exclusive preserve of those who consider themselves to be part of the ‘opposition’, but are also widespread among those who openly support the revolution. But in Cuba, for any protest or critical movement, to appear to be linked to US imperialism represents the kiss of death.

Once these links became known and entered the public domain, the N15 protest had zero chance of success. Yunior García himself, realising that it was going to be a flop, decided to call it off a few days prior. Alleging the potential for police repression, he advised his followers not to go out on N15.

To save face to the extent that he could, he announced that he would go out on 14 November alone, marching to the statue of Cuba’s independence hero, José Martí, in the Parque Central of Havana, to make an offering of a white flower.

He called on all Cubans to go out for a walk, individually, on the 15th, dressed in white and to organise pans and pots banging and clapping from their balconies. None of that unfolded.

Selective repression, with measures such as the arrest of well-known activists in the previous days, undoubtedly played a role.

But most important of all was the fact that the organisers had been politically discredited, and had additionally gone from being defiant to compliant towards the government.

Staying at home

On 14 November, Yunior García did not leave his house, as he had announced. His building was surrounded by an ‘act of repudiation’ made up mainly of women and plainclothes policemen.

It is important to note that these acts of repudiation have met with opposition and rejection by many of those who support the revolution, who consider that a political response must be given, and not one of personal harassment, which harks back to the worst times of the Stalinist repression of the Quinquenio Gris (the five grey years of 1971-76).

Faced with this situation, the man who styles himself as Cuba’s answer to Vaclav Havel [the Czech playwright who led the so-called ‘Velvet Revolution’ leading to capitalist restoration], stayed at home rather than going out alone, as he had announced his intention to do to his followers.

Had he attempted to leave his house, he would most likely have faced arrest, which would have caused an incident that the international media, Washington and Brussels would have used to redouble their campaign against the Cuban Revolution.

But it has subsequently become clear that he had already made his mind up to leave the island a couple of days later, showing the true caliber of his ‘leadership’ and the degree to which he is prepared to sacrifice for the cause in which he believes. Obviously, on Monday 15 November, the masses dressed in white did not materialise on the streets.

Defending the revolution

Another significant factor in the failure of 15 November was the fact that it coincided with official lifting of all restrictions on tourism and on children returning to face-to-face classes after many months of lockdown measures to contain the Covid-19 pandemic.

The lifting of restrictions has been possible due to the impressive mass vaccination campaign, with Cuban-made vaccines, which has led Cuba, in a short space of time, to become one of the countries with the highest vaccination rates in the world, including children over the age of two years.

In other words, the possibility of street protests was directly counterposed with its potential negative impact on tourism, which everyone understands is crucial for the Cuban economy; and on education, one of the most dearly held conquests of the revolution.

Anyone who believes that the main factor in the failure of N15 was the official ban on the protest and the police measures taken to implement it has understood nothing.

It is enough to look at other Latin American countries (e.g. Chile, Ecuador, Colombia to mention but a few recent examples) where the most brutal police repression has not only resulted in arrests, but has left people dead and maimed, and yet it has failed to prevent massive popular protests.

The Cuban Revolution faces very serious difficulties and it is obvious that there is a critical mood among broad sectors of the population.

But that does not mean that those who are critical are going to join a clearly counter-revolutionary demonstration, which is in open opposition to the conquests of the revolution, and which is linked to the very imperialist power that for 60 years has used every means in its attempts to crush the will of the Cuban people to decide their own future.

On the other hand, the failure of 15N does not mean that everything has returned to normal in Cuba. The problems facing the revolution (imperialist aggression, unequal terms of trade that Cuba experiences in the world market, the existence of the bureaucracy, etc.) are still there. They are serious and must be addressed.

The red scarves

For this reason, perhaps the most significant element of the developments in Cuba in recent days has been the sit-in of the red scarves. This is not because of its numerical importance, but rather because of its political importance.

And of course, none of the international media paid any regard to the activities of the red scarves. The vultures that they are, they had only come to the island seeking pictures of violence, repression, and the ‘fall of the regime’.

Shortly after the 11 July protests, a group of young Cuban revolutionaries decided to organise a public action against the blockade and in defense of the revolution, but to do so outside the official institutions. Finally, after delays in obtaining permission, a 48-hour sit-in was called at the statue of José Martí in central Havana, from Friday 12 to Sunday 14 November.

The organisers decided to call themselves ‘the red scarves’. Activists from various groups joined in – from the Martin Luther King Center, Cimarronas, La Tizza, the Our America Project, LGBT activists fighting for the new Family Code, artists and university students, etc.

The sit-in brought together dozens of revolutionaries for two days of culture, art, music and political discussions, braving inclement weather.

The character of the sit-in was analogous to that of the Tángana in the Trillo, the rally in defense of the revolution that was organised after the gathering in front of the Ministry of Culture on 27 November, 2020; and indeed, some of the participants were the same individuals, although the initial organising nucleus was different.

At that time, a group of young revolutionaries launched the call for a revolutionary rally in the Trillo park where the statue of the black Cuban patriot, Quintin Bandera, is located.

Quickly, the official institutions (UJC, FEU, etc.) tried to co-opt the event, smoothing over its most critical edges in order to turn it into a simple music festival, although they did not manage to completely drown out its political content.

The red scarf sit-in included a spectrum of political trends. But the common thread was that of clear opposition to the imperialist blockade, the defense of Cuba and of the revolution, whilst at the same time adopting a critical, left-wing stance. This was reflected in the political discussions that took place in parallel to the artistic-cultural activities.

‘Against false solutions’

One of the songs that Cuban troubadour Tony Ávila performed during the sit-in sums up the political spirit of the activity well.

In ‘Mi casa.cu’ [My Home.cu] Ávila talks about the changes that his house needs, but warns that these changes should in no way damage the house’s foundations. More than this, it is not just that the revolution needs a few changes while maintaining the basic conquests (which are based on state ownership of the means of production), but that the revolution and its foundations can only be defended by making those changes.

During the sit-in there was a very significant political speech given by Luís Emilio Aybar, from Proyecto Nuestra América and La Tizza, in which he once again emphasized a series of ideas contained in his recent articles:

“Those of us who are revolutionaries, communists, anti-imperialists, are aware of everything that is wrong, because we are part of the people and we suffer those evils, evils which can not only be explained by the blockade, but also because on many occasions we do things wrong, and we also want to combat that.”

Aybar clearly warned against “false solutions and false promises”:

“If the state companies do not work, we are told that they must be privatised. If they introduce a blockade against us, we are told that we have to surrender the country so they don’t block us.”

Mentioning the recent statements by President Díaz-Canel about peoples’ power, Aybar pointed out:

“The problem is that things cannot belong to everyone if we do not have power over them, the power to change them. Socialism is synonymous with the empowered people, people with the capacity to transform their reality, not with the powerless people”.

Clearly these are crucial questions and they point in the right direction. The planned economy needs workers’ democracy in the same way that the human body needs oxygen. Bureaucratic planning leads to waste, privilege, corruption, and laziness.

The conquests of the revolution can only be defended through the real and decisive participation of the working class in the management of the state and the economy.

“The best way to combat the counter-revolution is to make the revolution,” said Aybar, who ended his speech with a series of very significant slogans, chanted by the public, which included: “Down with bureaucratism, down with corruption, down with inequality, down capitalism, down with machismo, down with homophobia”, and its counterpart: “long live the revolution, long live Fidel and long live the socialism!”

Excelente la iniciativa de los @PanuelosRojos_ para defender la revolución cubana desde abajo y de manera autónoma. La conclusión de Luís Emilio Aybar de Nuestra America resume el carácter de la sentada de 48h de los #PanuelosRojos pic.twitter.com/2rlPOUiO6t

— Jorge Martin (@marxistJorge) November 15, 2021

Even sharper and more forceful was the intervention of Ariel Cabrera, a communist student from Santa Clara who could not travel to Havana but who left a message of support to the red scarves.

His statement was clearly anti-imperialist, but at the same time against the bureaucracy, against any attempt at capitalist restoration (“whether they come from declared enemies or those who call themselves friends”), and in favour of the workers having real power “in the workplaces and neighborhoods”, and in favour of “mechanisms of democratic worker’s management in state enterprises”.

What Cabrera raises here is absolutely correct. These are precisely the changes that the ‘house’ of the Cuban Revolution, to paraphrase Avila’s song, requires if it is to fight the attacks of the imperialists and the danger of capitalist restoration: workers’ control and workers’ democracy.

Workers’ control and international socialism

As could have been expected, at the end of the sit-in, President Díaz-Canel appeared, precisely when Tony Ávila was singing about the necessary reforms his house required. There was a clear attempt by the officialdom to politically co-opt the event.

Photos and reports of the sit-in of the red scarves and the presence of the president appeared in all the official media. However, none of them mentioned the most poignant speeches and discussions that took place there.

No mention was made about fighting bureaucratism. There was no reference to workers’ control or decision-making by workers. This also raises another question which must necessarily be addressed in order to defend the Cuban Revolution: the state media must be open to all currents of revolutionary opinion.

The creation of the ‘red scarves’ is significant in two very important ways: as a step forward in the autonomous organisation of young revolutionary communists; and in fostering the discussion of very advanced ideas about how to defend the Cuban Revolution. We welcome this initiative, and we vow to support and offer to participate in it in whatever way we can, as an absolutely necessary process of discussion and political clarification which has begun.

The position of the International Marxist Tendency is clear: We must defend the Cuban Revolution.

That means first of all opposing the imperialist blockade and the aggression to which the Cuban Revolution is subjected, and the defence of the nationalised character of the means of production on which its conquests are based.

We oppose capitalist restoration, and the bureaucracy’s control of the economy and the state, which undermines the revolution. The planned economy requires workers’ democracy, the democratic participation of the working class in all decisions.

The fight for the defense of the Cuban Revolution is also waged in the field of the international class struggle. Workers’ democracy has its corollary in proletarian internationalism – the struggle for international socialism that would break the isolation of the revolution.