On 24 April 1916 the Irish Citizen Army, together with the Irish Volunteers, rose up in arms against the might of the British Empire to strike a blow for Irish freedom and for the setting up of an Irish Republic. Their blow for freedom was to reverberate round the world, and preceded the first Russian Revolution by almost a year.

The background to the rebellion was the centuries of national oppression suffered by the Irish people in the interests of British landlordism and capitalism. In this they had the support of the Irish landlords and capitalists, of the Catholic hierarchy, who were linked by ties of interest to the Imperialists, and joined with them in fear of the Irish workers and peasants.

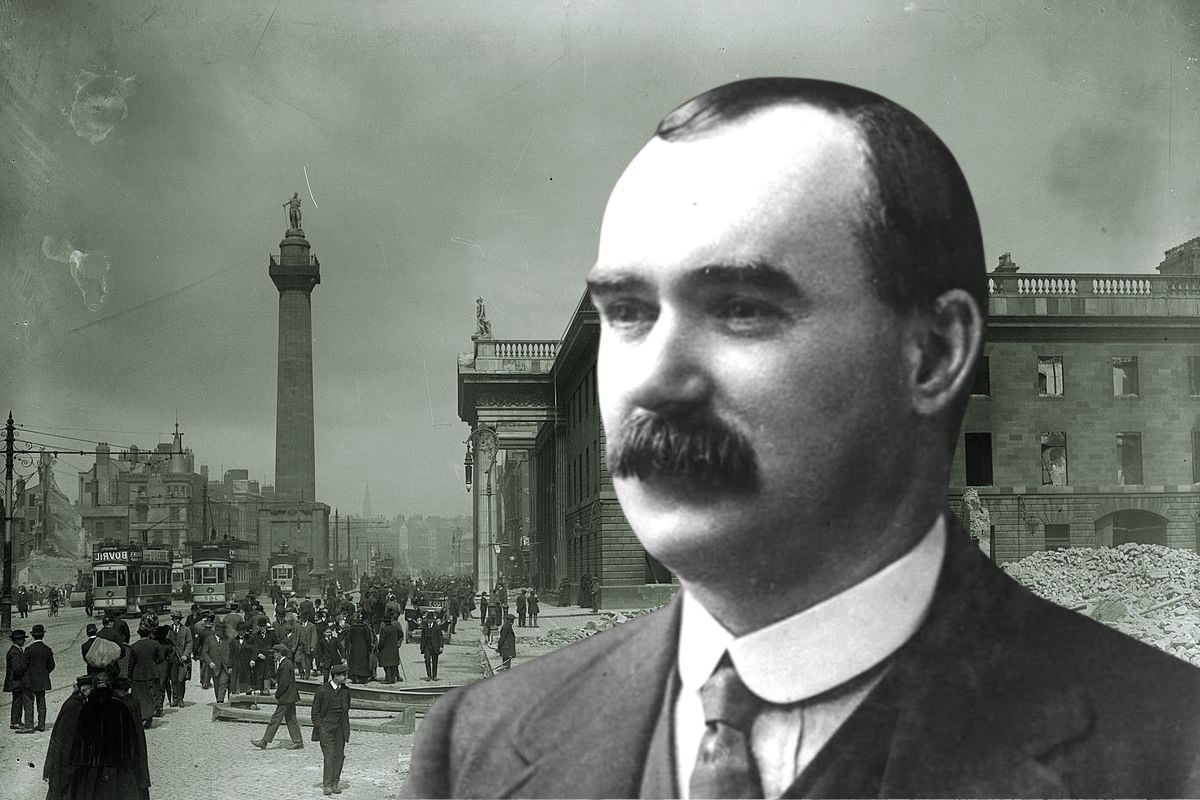

It is impossible to understand the Easter Rising without understanding the ideas of its leader, James Connolly, who considered himself a Marxist and based himself on the ideas of Internationalism and the class struggle. Like MacLean in Britain, Lenin and Trotsky, Liebknecht and Luxemburg and other Internationalists, Connolly regarded with horror the betrayal by the leaders of the Labour movement in all countries in supporting the Imperialist War. Dealing with the betrayal of the Second International, Connolly declared in his paper The Workers Republic:

“If these men must die, would it not be better to die in their own country fighting for freedom for their class, and for the abolition of war, than to go forth to strange countries and die slaughtering and slaughtered by their brothers that tyrants and profiteers might live?”

Protesting against the support by the British TUC of the war, Connolly wrote: “Time was when the unanimous voice of that Congress declared that the working class had no enemy except the capitalist class – that of its own country at the head of the list!”

Connolly stood for national freedom as a step towards the Irish Socialist Republic. But while the Stalinists and reformists today – 50 years after 1916 still mumble in politically incoherent terms about the need for the “national revolution against imperialism”, Connolly was particularly clear about the class question that was at the basis of the Irish question. Without being in direct contact with Lenin and Trotsky he had a similar position. “The cause of Labour is the cause of Ireland, and the cause of Ireland is the cause of Labour”, he wrote. “They cannot be dissevered. Ireland seeks freedom. Labour seeks that an Ireland free should be the sole mistress of her own destiny, supreme owner of all material things within and upon her soil”.

Connolly had no illusions in the capitalists of any country, least of all Ireland. On International capitalism he wrote:

“If, then, we see a small section of the possessing class prepared to launch into war, to shed oceans of blood and spend millions of treasure, in order to maintain intact a small portion of their privileges, how can we expect the entire propertied class to abstain from using the same weapons, and to submit peacefully when called upon to yield up forever all their privileges?”

And on the Irish capitalists:

“Therefore the stronger I am in my affection for national tradition, literature, language, and sympathies, the more firmly rooted I am in my opposition to that capitalist class which in its soulless lust for power and gold would bray the nations as in a mortar”. And again, “We are out for Ireland for the Irish. But who are the Irish? Not the rack-renting, slum-owning landlord; not the sweating, profit grinding capitalist; not the sleek and oily lawyer; not the prostitute pressmen – the hired liars of the enemy. Not these are the Irish upon whom the future depends. Not these, but the Irish working class, the only secure foundation upon which a free nation can be reared.”

Writing on the need for an Irish insurrection to expel British imperialism he wrote in relation to the World War: “Starting thus, Ireland may yet set the torch to a European conflagration that will not burn out until the last throne and the last capitalist bond and debenture will be shrivelled on the funeral pyre of the last War lord.”

As an answer to the demand for conscription which had been imposed in Britain and which was supported by the Irish capitalists for Ireland too, where the employers were exerting pressure to force Irish workers to volunteer, Connolly wrote:

“We want and must have economic conscription in Ireland for Ireland. Not the conscription of men by hunger to compel them to fight for the power that denies them the right to govern their own country, but the conscription by an Irish nation of all the resources of the nation – its land, its railways, its canals, its workshops, its docks, its mines, its mountains, its rivers and streams, its factories and machinery, its horses, its cattle, and its men and women, all co-operating together under one common direction that gather under one common direction that Ireland may live and bear upon her fruitful bosom the greatest number of the freest people she has ever known.”

He looked at the employers who were opposing conscription too from a critical class point of view:

“If here and there we find an occasional employer who fought us in 1913 (the Great Dublin lock-out in which the employers tried to break union organisation, but were defeated in this object by the solidarity of the Irish workers and their British comrades too) agreeing with our national policy in 1915 it is not because he has become converted, or is ashamed of the unjust use of his powers, but simply that he does not see in economic conscription the profit he fancied he saw in denying to his followers the right to organise in their own way in 1913.”

Answering objections to the firm working class point of view which he expounded he declared: “Do we find fault with the employer for following his own interests? We do not. But neither are we under any illusion as to his motives. In the same manner we take our stand with our own class, nakedly upon our class interests, but believing that these interests are the highest interests of the race.”

It is in this light that the uprising of 1916 must be viewed. As a consequence of the struggles of the past Connolly who was the General Secretary of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union had organised the Citizens Army for the purpose of defence against capitalist and police attack and for preparing for struggle against British imperialism. The Citizens Army was almost purely working class in composition: dockers, transport workers, building workers, printers and other sections of the Dublin workers being its rank and file.

It was with this force and in alliance with the more middle class Irish volunteers that Connolly prepared for the uprising. He had no illusions about its immediate success. According to William O’Brien, on the day of the insurrection Connolly said to him: “We are going out to be slaughtered.” He said “Is there no chance of success?” and Connolly replied “None whatsoever.”

Connolly understood that the tradition and the example created would be immortal and would lay the basis for future freedom and a future Irish Socialist Republic. In that lay his greatness. What a difference from the craven traitors of the German Socialist and Communist and Trade Union leaders who despite having three million armed workers supporting them, and with the sympathy and support of the overwhelming majority of the German working class (ready to fight and die, capitulated to Hitler without firing a shot.

Having said this, it is necessary to see not only the greatness of Connolly, sprung from the Irish workers, one of the greatest sons of the English speaking working class, and the effect of the uprising in preparing for the expulsion, at least in the Southern part of Ireland of the direct domination of British imperialism, but also the faults of both.

There was no attempt to call a general strike and thus paralyse the British Army. There was no real organisation or preparation of the armed struggle. No propaganda was conducted among the British troops to gain their sympathy and support. The leaders of the middle class Irish Volunteers were split. One of the leaders Eoin MacNeill countermanding orders for “mobilisation” and for “manoeuvres” and in the confusion only part of the Volunteers, joined with the Irish Citizens Army in the insurrection. Thus at the last minute the insurrection was betrayed by the vacillation of the middle class leaders, as they have betrayed many times in Irish history and in the history of other countries.

The British occupying troops suppressed the insurrection and then savagely executed its leaders, including the leader of the insurrection James Connolly, who was already badly wounded.

Connolly was murdered, but in the last analysis, British imperialism really suffered defeat.

Nowadays all sections of Irish society in the 26 counties hypocritically give support to the “brave and undying heroism of Connolly.” The Irish capitalists pretend to honour him. Connolly would have split contemptuously in their faces. He fought them, ever since he attained manhood, in the interests of the Irish workers and of International Socialism. But his most withered contempt would have been reserved for those in the Labour movement, including the leaders of the Labour Party and of the so-called Communist Parties, and of the various sects claiming to speak in the name of Irish Labour, who fifty years after Easter 1916, have not understood that unity of the Irish workers North and South can only be obtained by conducting the struggle on a class basis for an Irish Socialist Republic, in indissoluble unity with the British workers in their struggle for a British democratic Socialist Republic.

April 1966.