“In this sense, the theory of the Communists may be summed up in the single sentence: Abolition of private property…

“You [the bourgeoisie] are horrified at our intending to do away with private property. But in your existing society, private property is already done away with for nine-tenths of the population; its existence for the few is solely due to its non-existence in the hands of those nine-tenths.

“You reproach us, therefore, with intending to do away with a form of property, the necessary condition for whose existence is the non-existence of any property for the immense majority of society.”

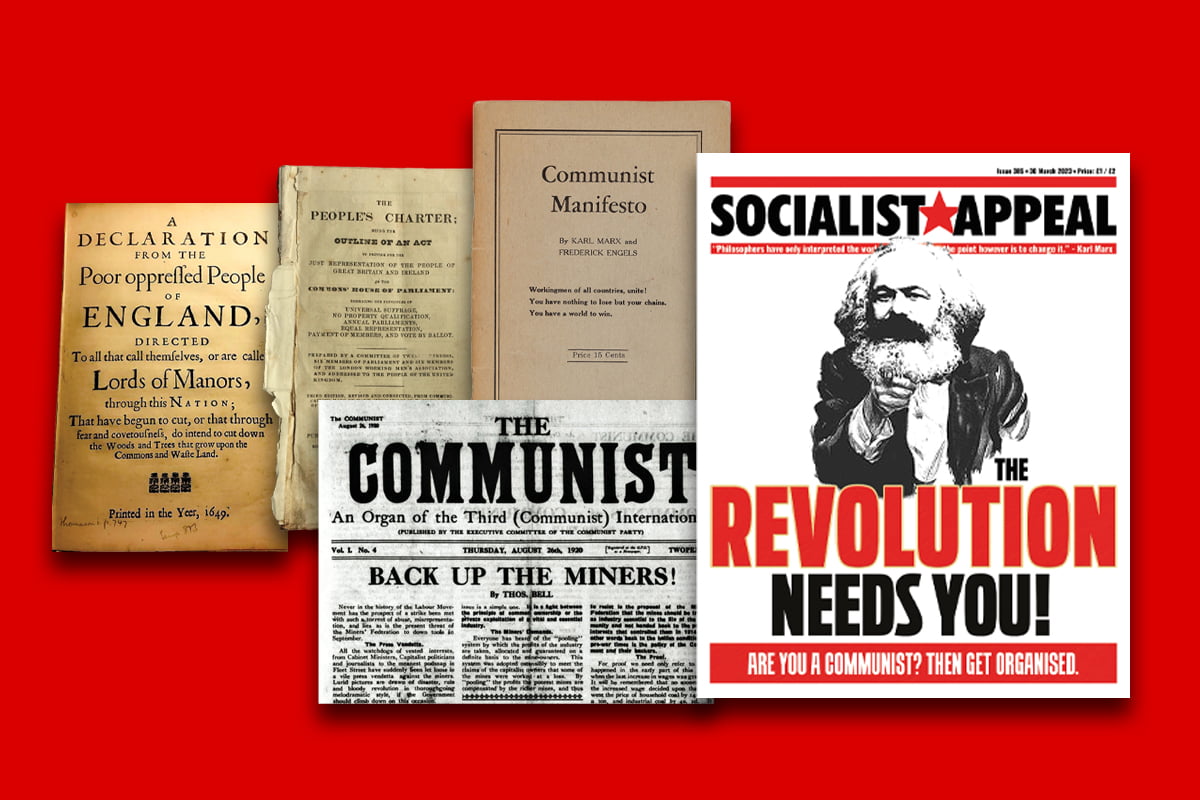

It is always said that communism is alien or foreign to our British way of life. Conservatism is traditionally regarded as the mainstay of the country. But the reality, when we look further, is somewhat different to this convention.

The ideas of communism have, in fact, very deep roots in British history, especially among the oppressed. In fact, the idea of a society founded, not on private property, but on common ownership has been around for a very long time.

William Morris wrote a wonderful account in 1890 about a future communist society, called News From Nowhere. Although dated, it gave a glimpse of the communist future, where want is abolished and people live in harmony. In Morris’ view, the Houses of Parliament would be turned into something actually useful, where farmyard manure was stored.

“Now, dear guest, let me tell you that our present parliament would be hard to house in one place, because the whole people is our parliament.”

The idea William Morris was conjuring up here was a vision of workers’ democracy.

“The idea of the woman being the property of the man, whether he was husband, father, brother, or whatnot. That idea has of course vanished with private property.”

Of course, communist ideas were not confined to Britain, but had an international character. Wherever exploitation exists, so does the idea of a society free from class oppression and violence, where everything is shared in common.

Peasant communism

In Britain, we can trace such ideas of communism back to the Middle Ages, despite the fact that the material conditions for a classless society did not as yet exist. It would take the advent of capitalism, with its industry and world market, to develop the productive forces to such a level as to make this realisable.

In the Middle Ages, the serfs, viciously exploited by the landowners, longed for a real paradise on Earth, where all wants are satisfied. This dream gave rise to the idea of the Land of Cokaygne, a utopian land where peace and plenty reigned. Here everything is possible:

“Geese fly roasted on the spit,

As God’s my witness, to that spot,

Crying out, ‘Geese, all hot, all hot!’

All is common to young and old,

To stout and strong, to meek and bold.”

This simple thought, of peasant communism, which runs through the Middle Ages, eventually evolved and led us to the ideas of communism of today.

The crisis of feudalism gave way to the struggles of John Ball and the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. In the words of the rebel-priest:

“Ah, ye good people, the matters goeth not well to pass in England, nor shall not do till everything be common, and that there be no villeins [serfs] nor gentlemen, but that we may be all equal…”

The emergence of private property and ‘government’ was regarded as the natural outcome of the Fall and man’s sinful state. There arose a desire for a return to a Golden Age, which embodied memories of an earlier primitive communism, where the state, private property, and classes did not exist.

Utopia

The rise of the bourgeoisie and the breakdown of feudalism gave rise to new class conflicts and ideas. We can witness the impact of Thomas More’s Utopia of the early 16th century, which is interwoven with communist ideas.

“The riche men not only by private fraud, but also by common laws do every day pluck and snatche away from the poore some part of their daily living… I can perceave nothing but a certain conspiracy of riche men procuring their owne commodities under the name and title of the commonwealth.”

There was to be no poverty in More’s Utopia, a communist society which rejected all luxuries. Jewels were to become simply the playthings of children. Gold, having lost its value, was used to make chamber pots. Funnily enough, Lenin also suggested gold under communism be used to build public toilets.

More’s vision, however, had no social force to turn it into reality. It took the upheavals of the English Civil War between Crown and Parliament, representing the bourgeois revolution, to stir up those forces. Those who dared to dream now wanted to make such ideas a reality.

The Diggers

The breakdown of censorship in class battles of the 1640s, resulted in the emergence of a host of radical sects. The most prominent were the Levellers. But the most left-wing were the Diggers – the True Levellers – led by Gerrard Winstanly.

As an agricultural-based society, everything was dependent on the land. The Diggers therefore demanded the common ownership of the land and went on to establish an agrarian communist settlement upon St George’s Hill in Surrey, as an example to be followed elsewhere.

While More’s Utopia was written in Latin, Winstanley’s writings were in English, appealing directly to the masses stirred into activity by the great revolution. While overlaced with religious phraseology, they have an overtly communist character.

“In the beginning of time,” wrote Winstanley, “the great creator Reason made the earth to be a common treasury.” But this was stolen and private property created by state power: “The sword brought in property and holds it up.” The earth ceased to be a common treasury and became “a place wherein one torments another”.

Although, in fact, it was the emergence of private property that gave rise to the development of the state, Winstanley was correct to see private ownership and appropriation as “the cause of all wars, bloodshed, theft, and enslaving laws that hold people under misery”. Only the abolition of private property can end “this enmity in all lands”.

With the defeat of the Digger and Leveller movement, the restoration of 1660 and then the Settlement of 1688 brought to power an alliance of sections of the aristocracy with the upper bourgeoisie. The rise of capitalism introduced a new dynamic – and the emergence of a new class, the industrial working class.

Robert Owen

Radical figures emerged with the impact of the French and American Revolutions, such as John Wilkes (1725-97), Thomas Paine (1737-1809), William Corbett (1763-1835), and Henry ‘Orator’ Hunt (1773-1835). But the figure who made the greatest impact was Robert Owen (1771-1858), a Welsh factory owner who became a socialist and visionary.

These were years of turmoil, with the rise of illegal trade unions and workers’ battles for democratic rights. Owen offered a way out of the misery of capitalist exploration through the establishment of communist colonies.

He was struck by the materialist philosophers of the Enlightenment, believing that a changed environment would change people’s characters.

In his cotton factory at New Lanark, he treated workers as human beings instead of slaves. He equipped it with a school and shop at low prices. This transformed workers and their families.

Owen wanted to apply this to the rest of society. But he soon realised that his appeals to the ruling class and the laws of capitalism were incompatible to the setting up of a socialist commonwealth.

He therefore tried himself to establish new model colonies in America and England, organised on the basis of full communism.

But they were to fail, as it was not possible to establish small islands of communism surrounded by an ocean of capitalism. The laws of capitalism would eventually prevail.

Owen believed three things stood in his way: private property, religion, and marriage in its present form.

Shunned by the ruling class, Owen turned directly to the newly-formed working class, establishing cooperatives and then trade unions. In 1834, he established the Grand National Consolidated Trades Union, which had a constitution calling for the overthrow of capitalism.

Owen’s ideas fed into the working class, including the fight for a new society. These ideas, together with the horrors of industrialisation, provided the fertile ground for the rise of the great Chartist movement.

Chartism

The Chartists created the first political party of the British working class. While it was based on six demands, beginning with the male adult vote and ending with annual parliaments, these were seen as a means to an end – a new egalitarian society.

The Chartist movement split between the reformists (‘moral force’) and the revolutionaries (‘physical force’), with the latter becoming the overwhelming majority. They engaged in mass petitions to general strikes, to insurrection, as in the Newport Rising.

To establish communism, the working class needed to conquer political power.

“What the people want is a government of the whole people to protect the whole people,” stated Bronterre O’Brien. “And this once acquired, they will be in a position to establish Owenism, or St. Simonism, or any other ‘ism’ that a majority may think best calculated to ensure the well-being of the whole.”

“The rich have never cared one straw for justice or humanity, since the beginning of the world,” he continued. “Force and force alone has ever subdued them into humanity.”

The Chartists were very much influenced by the 1848 revolution. This produced a communist wing, headed by Ernest Jones and Julian Harney, who were acquaintances of Marx and Engels.

“Emancipation of labour is the only worthy objective of political warfare,” stated Harney. “That those who till the soil shall be its first masters, that those who raise the food shall be its first partakers, that those who build mansions shall live in them.”

Harney’s paper, the Red Republican, published the first English translation of the Communist Manifesto, written by Marx and Engels. From then on, the struggle for communism, linked to the historic role of the working class, superseded utopian dreams.

“They [the Chartists] have progressed from the idea of simple political reform to the idea of a Social Revolution,” wrote Julian Harney.

Engels described it as “the union of Socialism with Chartism, the reproduction of French Communism in an English manner”.

Marxism

Marx and Engels had abandoned the term ‘socialist’, which was linked to middle-class utopian notions, for the word ‘communist’. They changed the woolly slogan “All Men are Brethren” to the class slogan “Proletarians of all lands unite”.

With the defeat of Chartism, which in many ways was an anticipation of future developments, Ernest Jones attempted to rally “the scattered ranks of Chartism on the sound principles of social revolution”.

But the changed objective situation, with the growth of capitalism, cut across these efforts. And Chartism gave way to the epoch of model unionism and class collaboration.

Nevertheless, the flame of communism was kept alive by Marx and Engels, who now lived in England. Together with the preparatory work of Jones and Harney, especially the formation of the Fraternal Democrats, they helped to found the First International in London in September 1864.

When the German revolutionary Weitling stated there was no English tradition of communism, Marx replied indignantly with a list:

“Thomas More, the Levellers, Owen, Thompson, Watts, Holyoake, Harney, Morgan, Southwell, Goldwyn Barmby, Greaves, Edmonds, Hobson, Spence will be amazed, or turn in their graves, when they hear that they are no ‘communists’…”

But it is in the 1880s that we see the revival in working-class militancy in the emergence of New Unionism, which unionised the unskilled and semi-skilled workers. With it came a revival of socialist and Marxist ideas.

In 1881, the Democratic Federation was formed, which changed its name three years later to become the Social Democratic Federation – an avowedly Marxist organisation, intent on spreading the ideas of communism.

They turned Marxism into a dogma, however, rather than a guide to action. It therefore remained a sect, incapable of linking the ideas of Marxism to the real movement of the working class.

The Independent Labour Party was created in 1893, but it professed a milk-and-water socialism. Engels nevertheless urged the small group of Marxists to join it and advocate communist ideas.

But Tom Mann, who was its secretary, gave up and turned to trade unionism, while Edward Aveling, Marx’s son-in-law, returned to the SDF. The void was filled with the likes of Ramsay MacDonald, a recent convert from liberalism.

When the Labour Party was formed in 1900, it was composed of the ILP, the SDF, and the trade unions. It was the beginning of a real mass workers’ party.

Within twelve months, however, the SDF had resigned after failing to get a resolution passed committing the party to common ownership of the means of production and class war. The Labour Party soon fell under the influence of reformism.

Communist Party of Britain

The SDF evolved in the years that followed and – in 1911 – became the British Socialist Party (BSP). In 1916, the party had ousted the pro-war faction around Hyndman, who then resigned. By this time, the BSP had affiliated to the Labour Party.

In 1917, radicalised by the imperialist war, the BSP were deeply supportive of the Bolshevik Revolution. Many of their members took part in the ‘Hands Off Russia’ Committee.

In 1919, a new (third) Communist International was formed. Lenin abandoned the old name of social-democratic, associated with the betrayal of 1914, for communist.

The Third International made an appeal for communist groups and parties to be established. In Britain, preparatory negotiations took place between different groups, the biggest being the BSP, to establish a Communist Party of Britain, as part of the Communist International.

The party was launched at the Unity Convention in London in August 1920, based upon the principles:

“(a) Communism as against capitalism…

“(b) The Soviet idea as against parliamentary (bourgeois) democracy…

“(c) Learning from history that dominant classes never yield to the revolutionary enslaved class without a struggle, the Communists must be prepared to meet and crush all the efforts of capitalist reactionaries to regain their lost privileges pending a system of thorough-going Communism. In other words, the Communist Party must stand for the dictatorship of the proletariat.”

Although numbering around 2,000 members, it drew to its ranks the cream of the working class. They soon began to lay plans for building a mass communist party.

Unfortunately, with the death of Lenin and the rise of Stalinism, the young communist parties were blown off course, including in Britain. From originally supporting world revolution, they adopted the Stalinist theory of ‘socialism in one country’.

This led to their nationalist and reformist degeneration. They simply sanctioned every twist and turn demanded by Moscow, and lauded the ‘socialist paradise’ in Russia and the ‘socialist’ countries without criticism.

The Soviet Union would eventually collapse, suffocated by a bureaucratic stranglehold. Without workers’ democracy, the state-owned planned economy was doomed. Its fall was not a collapse of ‘socialism’ or ‘communism’, but Stalinism, a bureaucratic one-party totalitarian state.

Today

Today, the small Communist Party of Britain, a shadow of its former self, has nothing in common with communism, except its name. But it is a misnomer. While paying lip-service to Marxism, it has long ago become a reformist party, no different from the Labour and trade union ‘lefts’.

Given the deepening crisis and turmoil of capitalism, the ideas of communism have once again become increasingly popular, especially amongst the youth.

The task before us remains the building of a genuine revolutionary communist party, based on the ideas of Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Trotsky. Our aim is the overthrow of capitalism in Britain and internationally, and the establishment of a world federation of socialist states.

On that basis, the old dreams of a classless society can be made a reality. And we can truly establish a paradise on Earth.