Several controversies have arisen in recent weeks around how key historical figures are popularly remembered. These controversies reveal that historical memory cannot be separated from contemporary class struggles.

“For history records the patterns of men’s lives, they say […] All things, it is said, are duly recorded – all things of importance, that is. But not quite, for actually it is only the known, the seen, the heard and only those events that the recorder regards as important that are put down, those lies his keepers keep their power by.”

(Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man, p. 439)

On 14 February, during a rapid-fire question-and-answer session for Politico, shadow chancellor John McDonnell was asked whether he considered Winston Churchill a hero or a villain. After a brief hesitation, McDonnell responded with “Tonypandy – villain”, referring to Churchill’s key role in the shooting of striking Welsh miners at Tonypandy in 1910.

This caused a wave of outrage in the capitalist media, exposing huge differences in how Churchill is remembered by different sections of British society.

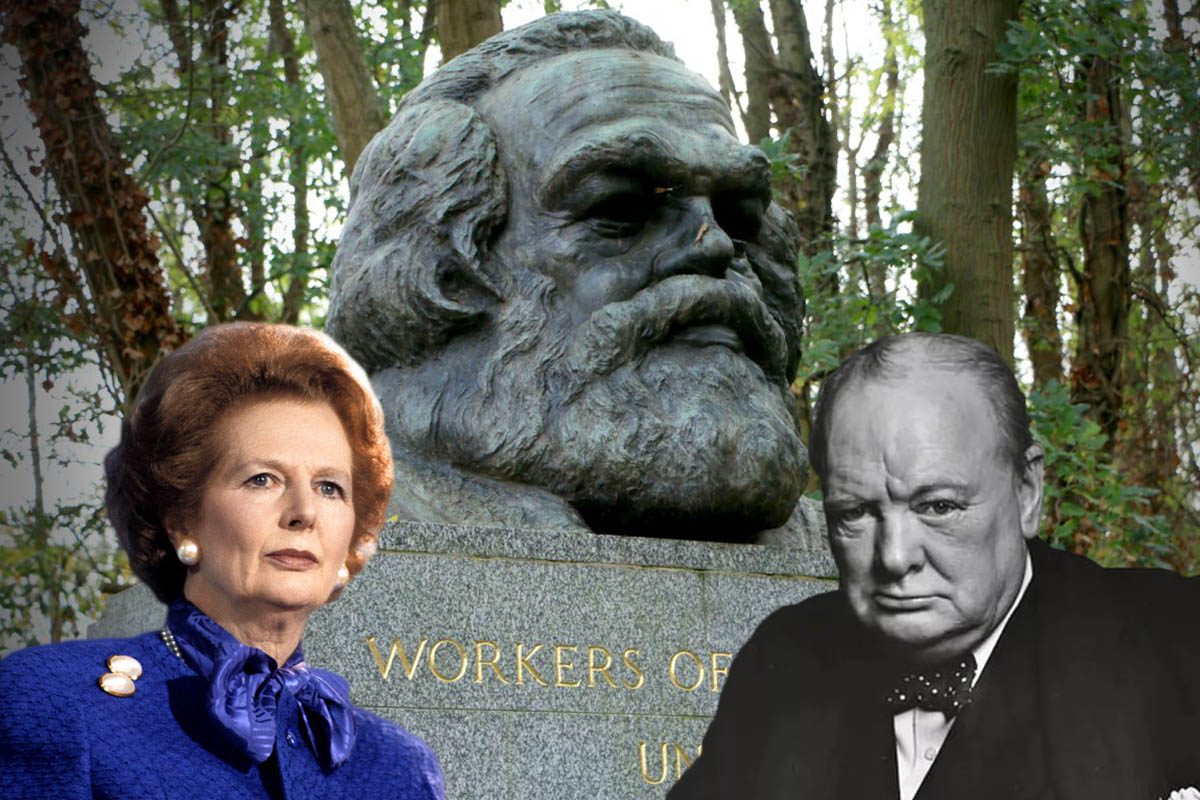

The controversy over Churchill’s villainy has come alongside several comparable debates about two other – diametrically opposed – historical figures: Karl Marx and Margaret Thatcher.

Marx’s grave in Highgate Cemetery has been vandalised twice this year, with the incidents occurring just weeks apart. Meanwhile, in Thatcher’s home-town of Grantham, plans for a statue of the former Prime Minister and sworn enemy of the labour movement have been approved, despite the expectation that this monument will face a campaign of vandalisation.

‘The past is not dead, it is not even past’

Taken together, what these events illustrate is the real, living relevance of history to current political developments. American author William Faulkner famously declared that “the past is not dead, it is not even past”. The truth of this could not be more clear in modern-day crisis-ridden Britain.

The historical narratives that infuse popular memory via museums, galleries, historical novels, films and television, popular history books, and public monuments are not neutral or objective reckonings with past events; they are ideological weapons in the struggle of the ruling class to maintain their power and wealth.

As such, the default position of many histories in the public domain is to elevate individual “Great Men” above wider social forces. History, as told to the working class, sentimentalises about the sacrifices made by oppressed people in the service of the capitalist class. It seeks to foster a sense of national destiny and cross-class identity. And it obscures the key role played by class struggle in changing society.

This is all clearly demonstrated in the sanctification of Churchill. Numerous commentators have responded to McDonnell’s comment by claiming that Churchill was singly responsible for taking Britain through the war, and even for defeating fascism in the 1940s. His image and ‘witty’ quotations are seen to embody a particular version of British national identity that is eccentric and stoic but ultimately heroic.

Having canonised Churchill in this way, the British ruling class mutes his many-millioned victims and opponents (including the similarly sanctified Gandhi, who Churchill wished to be stamped upon by an elephant and whose people he considered ‘ghastly’).

Many working-class people across Britain remember well how in 1945 their families eagerly voted Churchill out of office in favour of a Labour government promising substantial left-wing reforms.

They also remember Churchill’s leading role in breaking strikes: not only of Welsh miners in 1911, but of the whole trade union movement when in 1926 they embarked on a general strike against the Tory government. During this time, Churchill edited the anti-strike newspaper British Gazette.

On the wrong side of history

Indeed, on most historical questions Churchill is to be found on the wrong side. An unapologetic racist, he was responsible for – and unrepentant about – the Bengal famine of 1943 and he considered that “black people [are not] as capable or as efficient as white people”.

Indeed, on most historical questions Churchill is to be found on the wrong side. An unapologetic racist, he was responsible for – and unrepentant about – the Bengal famine of 1943 and he considered that “black people [are not] as capable or as efficient as white people”.

A determined champion of empire, he delighted in assertions of British power against colonial subjects, not only in far-off Africa and India, but in Ireland too, where he inflicted the notorious Black and Tans. A notorious sexist, he resisted the extension of women’s suffrage in 1928.

An anti-communist, he advocated for a more belligerent and aggressive British intervention into the Russian civil war, including the use of mustard gas. A sympathiser of fascism, he remarked positively about Mussolini’s regime in Italy.

Even as a military leader he was frequently incompetent, being disgraced by his support for the Gallipoli campaign in World War I and making substantial blunders during the Second World War in episodes such as the Norway Debate.

He has nevertheless been rehabilitated in popular memory by a relentless propaganda assault (initiated, indeed, by Churchill himself via his self-aggrandizing, 6-volume account of the war).

Memorials to Marx and Thatcher

When Margaret Thatcher died in 2013, an attempt was made in the media to similarly ignore and deny the deep and righteous hatred harboured towards her by people from the communities she destroyed, and by their allies across the labour movement. This narrative was rudely disrupted, however, by the eruption of lively celebrations in many places across Britain.

Attempts to erect a statue of her have since been fiercely resisted. Now though, Grantham council have approved plans for a £300 000, 20ft high bronze sculpture in the likeness of the so-called Iron Lady, to be mounted on a 10ft plinth for fear of vandalism. How this statue will fare remains to be seen. But its erection is evidence that as long as the power of the capitalist class remains intact, they will continue to try and write a history that suits them.

Such a history is being used by anonymous vandals to desecrate the grave of Karl Marx in London. The grave was first attacked at the start of February with a hammer. After the limited damage from this attack was repaired, the monument was spray-painted with anti-Communist slogans branding Marxism a “doctrine of hate” and claiming that Bolshevism was responsible for a “genocide”.

Vandals back at Marx Memorial, Highgate Cemetery. Red paint this time, plus the marble tablet smashed up. Senseless. Stupid. Ignorant. Whatever you think about Marx’s legacy, this is not the way to make the point. pic.twitter.com/hGKBMYGWNy

— Highgate Cemetery (@HighgateCemeter) February 16, 2019

These daubings weaponise the hysterical death-count inflation found in books such as The Black Book of Communism and the works of Robert Conquest and Jung Chang. These are used to delegitimise Marx as a revolutionary a thinker of world-historical significance. They form part of a very deliberate effort on the part of the ruling class to blacken the banner of Bolshevism and thereby disarm the labour movement.

Clearly, this attack on Marx’s grave demonstrates that his ideas are still powerful and relevant in the eyes of their enemies. Similarly, the controversies around how Thatcher and Churchill are remembered demonstrate the emotiveness and resonance of their reactionary influence.

As Marxists, we must act as the historical memory of the working class in the continuing fight for dignity, freedom, and socialism. In so doing, we make no apologies for celebrating the legacies of Marxism and Bolshevism, and have no qualms about condemning both Churchill and Thatcher as villains.