Lenin wrote in State and Revolution:

“What is now happening to Marx’s theory has, in the course of history, happened repeatedly to the theories of revolutionary thinkers and leaders of oppressed classes fighting for emancipation. During the lifetime of great revolutionaries, the oppressing classes constantly hounded them, received their theories with the most savage malice, the most furious hatred and the most unscrupulous campaigns of lies and slander. After their death, attempts are made to convert them into harmless icons, to canonize them, so to say, and to hallow their names to a certain extent for the ‘consolation’ of the oppressed classes and with the object of duping the latter, while at the same time robbing the revolutionary theory of its substance, blunting its revolutionary edge and vulgarizing it.”

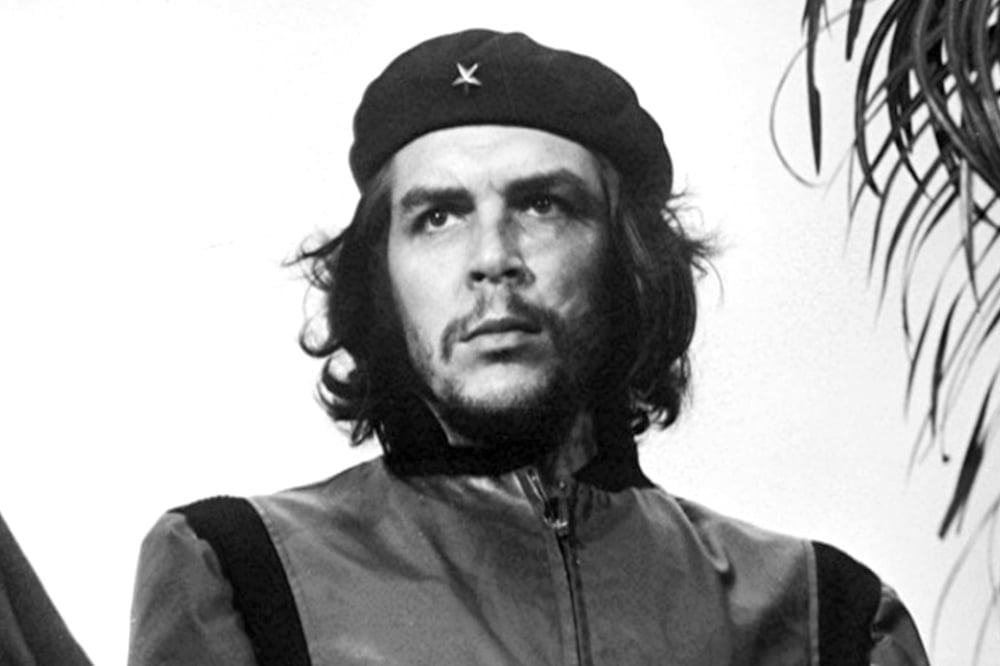

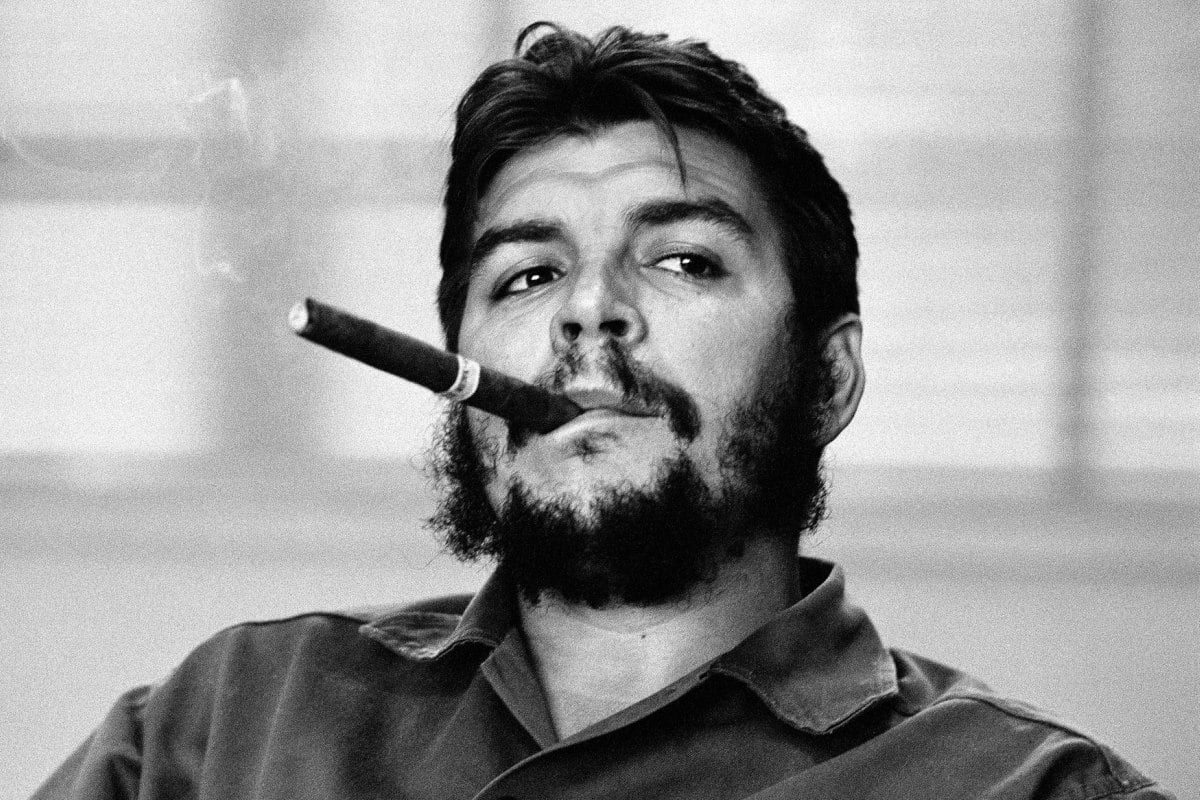

After his death, Guevara became an icon of socialist revolutionary movements and a key figure of modern pop culture worldwide. The Alberto Korda photo of Che has become famous, appearing on t-shirts and protest banners all over the world. Thus, Che has become an icon of our times. After the death of Lenin, the leading clique of Stalin and Zinoviev created a cult around his figure. Against Krupskaya’s wishes, his body was embalmed and placed on public display in the mausoleum in Red Square. Later Krupskaya stated: “All his life Vladimir Ilyich was against icons, and now they have turned him into an icon.”

In November 2005, the German magazine Der Spiegel wrote about Europe’s “peaceful revolutionaries” whom it describes as the heirs of Gandhi and Guevara [!]. This is a complete travesty. We should form a “Society for the Protection of Che Guevara” against the people who have nothing to with Marxism, the class struggle or socialist revolution, and who wish to paint an entirely false picture of Che as a kind of revolutionary saint, a romantic petty bourgeois, an anarchist, a Gandhian pacifist or some other nonsense of the sort.

Our attitude to this outstanding revolutionary is similar to the attitude of Lenin towards Rosa Luxemburg. While not concealing his criticisms of the mistakes of Rosa Luxemburg, Lenin held Rosa Luxemburg in high regard as a revolutionary and internationalist. Here is what he wrote about Rosa, defending her memory against the reformists and Mensheviks:

“We shall reply to this by quoting two lines from a Russian fable, ‘Eagles may at times fly lower than hens but hens can never rise to the height of eagles’. [Rosa ] in spite of her mistakes […] was and remains for us an eagle. And not only will Communists all over the world cherish her memory, but her biography and her complete works will serve as useful manuals for training many generations of communists all over the world. ‘Since August 4, 1914, German social-democracy has become a stinking corpse’ ‑ this statement will make Rosa Luxemburg’s name famous in the history of the international working class movement. And, of course, in the backyard of the working class movement, among the dung heaps, hens like Paul Levi, Scheidemann, Kautsky and all their fraternity will cackle over the mistakes committed by the great Communist”. (Lenin Collected Works, Vol. 33, p. 210, Notes of a Publicist, Vol. 33).

Che’s life in summary

- Born June 14, 1928 in Argentina as Ernesto Guevara – the eldest of five children.

- 1948: Attends university in Buenos Aires.

- 1950/51: embarks on two long journeys: a 4500 km long solo journey on bicycle through the rural provinces of Northern Argentina in 1950, and a nine-month, 8,000-kilometer continental motorcycle trek through most of South America..

- The notes taken during the two trips evolved to form a book, entitled ‘The Motorcycle Diaries.’

- 1953: Obtains medical degree. Becomes politically active, first in native Argentina and later at Bolivia and Guatemala. Studies writings of Marx.

- 1955: Introduced to Cuban revolutionary leader, Fidel Castro.

- 1956: Troops loyal to Castro initiates the 26th of July Movement.

- 1958: Guevara plays a critical role in the Battle of Las Mercedes

- January 8, 1959: Fidel Castro takes control of Havana. Batista regime overthrown by revolution.

- June 1959: Made Minister of Industries. Later also made Finance Minister and President of National Bank.

- 1960: Visits China and Soviet Union. He sharply criticizes the Soviet bureaucracy.

- 1962: Cuban missile crisis.

- 1965: Leaves Cuba to set up guerrilla troops, first in the Congo and later in Bolivia.

- 1967: Captured and executed in Bolivia on October 9th.

Early life

Ernesto Guevara de la Serna (14th June 1928 – 9th October, 1967), generally known as Che Guevara was a Marxist revolutionary – Argentinean by birth but an internationalist to the marrow of his bones. His ancestry, like that of most people in Latin America, was very mixed. Guevara is a Castilianized form of the Basque Gebara, signifying “from the Basque province of Araba (Alava)”. One of his family names, Lynch, was Irish (the Lynch family was one of the 14 Tribes of Galway). The mixture of Basque and Irish blood is somewhat explosive!

Born into a middle class family, he did not suffer poverty and hunger like so many other children in Latin America. But he suffered from ill health. His naturally adventurous and rebellious spirit was connected with the fact that from an early age he had a serious asthmatic condition. He spent all his life trying to overcome this problem by deliberately driving himself to the limit. His steely determination to overcome all difficulties may also be traced back to this.

His humanitarian instincts first inclined him to the field of medicine. He obtained a medical degree. His specialty was dermatology and he was particularly interested in leprosy. At this time his horizons were no wider than those of most other middle class young men: to work hard, get a degree in medicine, get a good job, maybe do original research into medical science and advance human knowledge by some amazing discovery. About this period in his life he wrote:

“When I began to study medicine most of the concepts I now have as a revolutionary were then absent from my warehouse of ideals. I wanted to be successful, as everyone does. I used to dream of being a famous researcher, of working tirelessly to achieve something that could, decidedly, be placed at the service of mankind, but which was at that time all about personal triumph. I was, as we all are, a product of my environment.”

Like most young people, Ernesto loved to travel. He was seized by what the Germans call “Wanderlust”. He wrote: “I now know by an unbelievable coincidence of fate that I am destined to travel.” Just how far he was to travel, and in what direction he would go, was as yet a sealed book to him. No doubt he would have made a conscientious physician, but the Wanderlust got the better of him. He took to the road, and did not to return to Argentina for many years. His adventurous nature induced him to set out on a long journey travelling rough throughout South America on a motorbike.

The link between medicine and his political ideals emerged in a speech that he delivered in the San Pablo leprosarium in Peru on the occasion of his 24th birthday. He said:

“Although we’re too insignificant to be spokesmen for such a noble cause, we believe, and this journey has only served to confirm this belief, that the division of America into unstable and illusory nations is a complete fiction. We are one single mestizo race with remarkable ethnographical similarities, from Mexico down to the Magellan Straits. And so, in an attempt to break free from all narrow-minded provincialism, I propose a toast to Peru and to a United America.”(Motorcycle Diaries, p.135).

Early awakenings

This journey was the beginning of a long odyssey that slowly opened his eyes to the reality of the world in which he lived. For the first time in his life he was brought into direct contact with the impoverished and oppressed masses of the continent. He witnessed at first hand the appalling conditions in which the majority of people lived. That such dreadful poverty should exist amidst all the natural wealth and beauty of this wonderful continent made a deep impression on his young mind.

These contradictions moved his passionate and sensitive nature and caused him to mediate on their causes. Che always had an eager and inquiring mind. That same intellectual fervour that he showed in his study of medicine was now turned to the study of society. The experiences and observations he had during these trips left a lasting mark on his consciousness.

Suddenly all his earlier ambitions for personal advancement seemed petty and uninteresting. After all, a doctor can cure individual patients. But who can cure the terrible disease of poverty, illiteracy, homelessness and oppression? One cannot cure cancer with an aspirin, and one cannot cure the underlying ills of society with palliatives and half-measures.

Slowly in the mind of this young man a revolutionary idea was maturing and developing. He did not immediately become a Marxist. Who does? He thought long and hard, and read widely: a habit that never left him to the end of his life. He began to study Marxism. Gradually, imperceptibly, but with a steely inevitability, he became convinced that the problems of the masses could only be remedied by revolutionary means.

Guatemala

His conversion to conscious Marxism received a decisive impetus when he went to Guatemala to learn about the reforms being implemented there by President Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán. In December 1953 Che arrived in Guatemala where Guzmán headed a reformist government, which was attempting to carry out a land reform and demolish the latifundia system.

Even before arriving in Guatemala Guevara was a committed revolutionary, although his views were still in a formative stage. This is shown by a letter written in Costa Rica on 10 December 1953, in which he says: “En Guatemala me perfeccionaré y lograré lo que me falta para ser un revolucionario auténtico.” (“In Guatemala I will perfect myself and gain everything I still lack to be a real revolutionary”: Guevara Lynch, Ernesto. Aquí va un soldado de América. Barcelona: Plaza y Janés Editores, S.A., 2000, p. 26.).

But the United Fruit Company and the CIA had other ideas. They organized a coup attempt led by Carlos Castillo Armas, with US air support. Guevara immediately joined an armed militia organized by the Communist Youth; but was frustrated with the group’s inaction. After the coup, the arrests began and Che had to seek refuge in the Argentine consulate where he remained until he received a safe-conduct pass. He then decided to make his way to Mexico.

His experience of the US-sponsored coup against Arbenz confirmed him in his views and led him to draw certain conclusions. It concentrated Che Guevara’s mind on the role of the United States in Latin America. Here was an imperialist power that was a bulwark of all the reactionary forces throughout the continent. Any government that tried to change society would inevitably face the implacable opposition of a powerful and ruthless enemy.

After the victory of the CIA-inspired coup, Che was forced to flee to Mexico where, in 1956, he joined Fidel Castro’s revolutionary 26th of July Movement, which was engaged in a ferocious struggle against the dictatorship of General Fulgencio Batista in Cuba. The two men seemed to strike up an immediate rapport. Castro needed reliable men and Che needed an organization and a cause for which to fight.

Che had seen with his own eyes the fatal weakness of reformism and this confirmed in him the belief that socialism could only be achieved through armed struggle. He arrived in Mexico City in early September 1954, and entered into contact with Cuban exiles whom he had met in Guatemala. In June 1955 he met first Raúl Castro, and then his brother Fidel, who had been amnestied from prison in Cuba, where he had been confined after the failure of the assault on the Moncada Barracks.

Che immediately joined the 26th of July Movement that was planning to overthrow the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista. At first Che was supposed to play a medical role. His poor health (he suffered from asthma all his life) did not suggest a warrior’s constitution. Nevertheless, he participated in military training side by side with the other members of the Movement, and proved his worth.

Granma

On November 25th, 1956, the cabin cruiser Granma set out from Tuxpan, Veracruz heading for Cuba, loaded with revolutionaries. It was an old ship and it was carrying many more people than it was designed for. It nearly sank in the heavy weather that reduced many of the passengers to severe seasickness. This was only the beginning of their problems.

On November 25th, 1956, the cabin cruiser Granma set out from Tuxpan, Veracruz heading for Cuba, loaded with revolutionaries. It was an old ship and it was carrying many more people than it was designed for. It nearly sank in the heavy weather that reduced many of the passengers to severe seasickness. This was only the beginning of their problems.

The expedition was almost destroyed right at the outset. They landed in the wrong place and were caught in the swamps. They were attacked by government troops soon after landing, and about half of the rebels were killed or executed after being captured. Only 15-20 survived. This battered and depleted force somehow managed to re-group and escape into the Sierra Maestra Mountains from where they waged a guerrilla war against the Batista dictatorship.

Despite the initial setback, the rebels had struck a courageous blow, which resonated in the hearts and minds of the masses and especially the youth. New recruits filled up their depleted ranks. The guerrilla war spread throughout eastern Cuba. Che had been taken on as a medic, but in the heat of battle he had to make up his mind whether he could serve the cause best as a doctor or a fighter. He decided:

“Perhaps this was the first time I was confronted with the real-life dilemma of having to choose between my devotion to medicine and my duty as a revolutionary soldier. Lying at my feet were a knapsack full of medicine and a box of ammunition. They were too heavy for me to carry both of them. I grabbed the box of ammunition, leaving the medicine behind “ (Quizás esa fue la primera vez que tuve planteado prácticamente ante mí el dilema de mi dedicación a la medicina o a mi deber de soldado revolucionario. Tenía delante de mí una mochila llena de medicamentos y una caja de balas, las dos eran mucho peso para transportarlas juntas; tomé la caja de balas, dejando la mochila ….”)

The main strength of the rebellion lay in the chronic weakness of the old regime, which was internally rotted with corruption and decay. Despite the support, money and arms of US imperialism, Batista was unable to check the advance of the revolution. His soldiers were unwilling to risk their lives to defend a diseased regime. Weakened and demoralized by a series of ambushes in the heights of the Sierra Maestra, at Guisa and Cauto Plains, the army was already thoroughly demoralized when the final offensive was launched.

In this campaign Che became a Comandante, gaining a reputation for courage, bravery and military skill. He was now second only to Fidel Castro himself. In the final days of December 1958, Comandante Guevara and his column of fighters headed west for the final push towards Havana. This column undertook the most dangerous tasks in the decisive attack on Santa Clara. In a speech given in Palma Soriano on December 27, 1983), Castro pointed out the importance of this offensive:

“We established our defensive line on the Cautillo River. We had Mapos surrounded, but there was still Palma. There were approximately 300 enemy soldiers. We had to take Palma. We were also anxious to take the arms that were to be found in Palma, because when we left La Plata, in the Sierra Maestra, because of the latest offensive, we left with 25 armed soldiers and 1,000 unarmed recruits. We armed those troops along the way. We armed them during the fighting, but we really finished fully arming them in Palma.”

The final orders to the rebel army were issued from Palma on January 1, 1959. But the final blow that finished off the dictatorship was the general strike of the workers of Havana. The whole edifice was collapsing like a house of cards. Batista’s generals were attempting to negotiate a separate peace with the rebels. When he learned of this, the dictator realized that the game was up and fled to the Dominican Republic on New Year’s Day, 1959.

In power

The old bourgeois state had been smashed and a new power was formed, or rather improvised, on the basis of the guerrilla army. Power now passed into the hands of the guerrilla army. Marxists all over the world rejoiced at the victory of the Cuban Revolution. This was a heavy blow stuck at imperialism, capitalism and landlordism on the doorstep of the most powerful imperialist state in history. It gave hope to the oppressed masses everywhere. Yet the way in which it took place was different to the Russian Revolution of October 1917. There were no soviets and the working class, although it had ensured the final victory of the Revolution through a general strike, did not play a leading role.

The old bourgeois state had been smashed and a new power was formed, or rather improvised, on the basis of the guerrilla army. Power now passed into the hands of the guerrilla army. Marxists all over the world rejoiced at the victory of the Cuban Revolution. This was a heavy blow stuck at imperialism, capitalism and landlordism on the doorstep of the most powerful imperialist state in history. It gave hope to the oppressed masses everywhere. Yet the way in which it took place was different to the Russian Revolution of October 1917. There were no soviets and the working class, although it had ensured the final victory of the Revolution through a general strike, did not play a leading role.

There are some who argue that this is irrelevant, that every revolution is different, that there cannot be a model that is applicable to all cases, and so on. To some extent this is true. Every revolution has its own concrete features and characteristics that correspond to the different concrete conditions, class balance of forces, history and traditions of different countries. But this observation by no means exhausts the question.

“The dictatorship of the proletariat”

Marx explained that the workers cannot simply lay hold of the old state apparatus and use it to change society. He developed his theory of workers’ power in The Civil War in France: Address of the General Council of the International Working Men’s’ Association, 1871. What is the essence of this theory? Marx explained that the old state could not serve as an instrument to change society. It had to be destroyed and replaced with a new state power – a workers’ state – that would be completely different to the old state machine, “the centralized state power, with its ubiquitous organs of standing army, police, bureaucracy, clergy, and judicature”. It would be a semi-state, to use Marx’s expression, dedicated to its own disappearance:

“The Commune was formed of the municipal councillors, chosen by universal suffrage in the various wards of the town, responsible and revocable at short terms. The majority of its members was naturally working men, or acknowledged representatives of the working class. The Commune was to be a working, not a parliamentary body, executive and legislative at the same time.

“Instead of continuing to be the agent of the Central Government, the police was at once stripped of its political attributes, and turned into the responsible, and at all times revocable, agent of the Commune. So were the officials of all other branches of the administration. From the members of the Commune downwards, the public service had to be done at workman’s wage. The vested interests and the representation allowances of the high dignitaries of state disappeared along with the high dignitaries themselves. Public functions ceased to be the private property of the tools of the Central Government. Not only municipal administration, but the whole initiative hitherto exercised by the state was laid into the hands of the Commune.

“Having once got rid of the standing army and the police – the physical force elements of the old government – the Commune was anxious to break the spiritual force of repression, the “parson-power”, by the disestablishment and disendowment of all churches as proprietary bodies. The priests were sent back to the recesses of private life, there to feed upon the alms of the faithful in imitation of their predecessors, the apostles.” (Marx, The Civil War in France, The Third Address, May, 1871 [The Paris Commune])

This bears absolutely no relation to the bureaucratic totalitarian regime of Stalinist Russia where the state was a monstrous repressive power standing above society. Even the word “dictatorship” in Marx’s day had an entirely different connotation to that which we attach to it today. After the experience of Stalin, Hitler, Mussolini, Franco and Pinochet the word dictatorship signifies concentration camps, the Gestapo and the KGB. But Marx actually had in mind the dictatorship of the Roman Republic, whereby in a state of emergency (usually war) the usual mechanisms of democracy were temporarily suspended and a dictator ruled for a temporary period with exceptional powers.

Far from a totalitarian monster, the Paris Commune was a very democratic form of popular government. It was a state so constructed that it was intended to disappear – a semi-state, to use Engels’ expression. Lenin and the Bolsheviks modelled the Soviet state on the same lines after the October Revolution. The workers took power through the soviets, which were the most democratic organs of popular representation ever invented.

Despite the conditions of terrible backwardness in Russia the working class enjoyed democratic rights. The 1919 Party programme specified that, “all the working masses without exception must be induced to take part in the work of state administration”. Direction of the planned economy was to be mainly in the hands of the trade unions. This document was immediately translated into all the main languages of the world and widely distributed. However, by the time of the Purges in 1936 it was already regarded as a dangerous document and all copies of it were quietly removed from all libraries and bookshops in the USSR.

In any revolution where the leading role is not played by the working class but other forces, certain things will inevitably flow. There is always a tendency for the state to rise above the rest of society and even the most dedicated people can be corrupted or lose contact with the masses under certain circumstances. That is why Lenin devised his famous four conditions for workers’ power:

- Free and democratic elections with right of recall of all officials.

- No official to receive a higher wage than a skilled worker.

- No standing army but the armed people.

- Gradually, all the tasks of running society to be done by everybody in turn (when everybody is a bureaucrat nobody is a bureaucrat).

These conditions were not a caprice or an arbitrary idea of Lenin. In a nationalized planned economy it is absolutely necessary to ensure the maximum of participation of the masses in the running of industry, society and the state. Without that, there will inevitably be a tendency towards bureaucratism, corruption and mismanagement, which can ultimately undermine and destroy the planned economy from within. That is just what happened to the USSR. The points raised by Lenin have an important bearing on the events in Cuba and on Che’s own evolution.

Revolutionary minister

Che occupied various posts in the revolutionary administration. He worked at the National Institute of Agrarian Reform, and was President of the National Bank of Cuba, when he signed banknotes with his nickname, “Che”. All this time, Guevara refused his official salaries of office, drawing only his lowly wage as an army comandante.

This little detail tells us a lot about the man. He maintained that he did this in order to set a “revolutionary example”. In fact, he was following to the letter the principle laid down by Lenin in State and Revolution that no official in the Soviet state should receive a salary higher than a skilled worker. This was an anti-bureaucratic measure. Lenin, like Marx, was well aware of the danger of the state raising itself above society and that this danger also existed in a workers’ state.

Taking as his point of departure Marx and Engels’ analysis of the Paris Commune, Lenin put forward four key points to fight bureaucracy in a workers’ state in 1917 to which we have already referred to above.

“We shall reduce the role of state officials,” wrote Lenin, “to that of simply carrying out our instructions as responsible, revocable, modest paid ‘foremen and accountants’ (of course, with the aid of technicians of all sorts, types and degrees). This is our proletarian task, this is what we can and must start with in accomplishing the proletarian revolution.” (LCW, Vol. 25, p. 431.).

During the first months of Soviet rule the salary of a People’s Commissar (including Lenin himself) was only twice the minimum subsistence wage for an ordinary citizen. Over the next years, prices and the value of the ruble often changed very rapidly and wages altered accordingly. At times the figures were quite astonishing – hundreds of thousands and millions of rubles. But even under these conditions Lenin made sure that the ratio between lowest and highest salaries in state organizations did not exceed the fixed limit – during his lifetime the differential apparently was never greater than 1:5.

Of course, under conditions of backwardness, many exceptions had to be made which represented a retreat from the principles of the Paris Commune. In order to persuade the “bourgeois specialists” (spetsy) to work for the Soviet state, it was necessary to pay them very large salaries. Such measures were necessary until the working class could create its own intelligentsia. In addition, special “shock worker” rates were paid for certain categories of factory and office workers, and so on.

However, such compromises did not apply to Communists. They were strictly forbidden to receive more than a skilled worker. Any income they received in excess of that figure had to be paid over to the Party. The chair of the Council of People’s Deputies received 500 rubles, comparable to the earnings of a skilled worker. When the office manager of the Council of People’s Deputies, V. D. Bonch-Bruevich paid Lenin too much in May 1918, he was given “a severe reprimand” by Lenin, who described the rise as “illegal”.

Due to the isolation of the revolution, and the need to employ bourgeois specialists and technicians the differential was increased for these workers – they could earn a wage 50 per cent more than that received by the members of the government. Lenin was to denounce this as a “bourgeois concession”, which should be reduced as rapidly as possible.

Not only in theory but in practice, Che adhered to similar revolutionary principles.

Che versus Stalinism

Che Guevara was an instinctive revolutionary. He was personally incorruptible and detested bureaucracy, careerism and privileges. His was the stern and puritan morality of the revolutionary fighter. Therefore, he was repelled by the manifestations of bureaucracy and flunkeyism that he observed after the victory of the Revolution.

Che often expressed opinions in opposition of the official positions of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union under Nikita Khrushchev. He was opposed to the “theory” of peaceful coexistence. He did not like the slavish attitude of some Cubans towards Moscow and its ideology. Above all, bureaucracy, careerism and privilege repelled him. His visits to Russia and Eastern Europe shocked him and deepened his sense of disillusionment with Stalinism. The bureaucracy, privileges and suffocating conformism repelled him to the depths of his soul.

He became increasingly critical of the Soviet Union and its leaders. That is why he initially inclined to China in the Sino-Soviet dispute. But to portray Che as a Maoist is to do him an injustice. There is no reason to believe that he would have felt any more at home in Mao’s China than in Khrushchev’s Russia. The reason he appeared to lean to China was that the Chinese criticized Moscow’s decision to remove the Soviet missiles from Cuba, an act that Che looked on as a betrayal.

It is impossible to arrive at a neat classification of Che Guevara. He was a complex character with a fertile brain that was always seeking after truth. The dogmas of Stalinism were the absolute antithesis of his way of thinking. He was repelled by bureaucratic servility and conformism and detested privilege of any sort. This made him an object of suspicion to visiting “Communist” dignitaries from Europe and the Soviet Bloc. The Stalinist leaders of the French Communist Party were particularly hostile to him and even launched a campaign of calumnies against Che, describing him as a “petty bourgeois adventurer”.

Minister of Industries

Guevara later served as Minister of Industries, in which post he grappled with the problems of building a socialist planned economy in the difficult conditions that confronted the Cuban Revolution. My good friend and comrade Leon Ferrera, the veteran Cuban Trotskyist, worked with Che in the Ministry and had many discussions with him about Trotsky and Trotskyism. He gave him Trotsky’s books to read and he showed some interest in them. But there was one point he could not grasp: “Trotsky writes a lot about the bureaucracy, but what does this mean”. Leon explained as best he could, and after a while Che said: “Yes, I think I understand what you mean.”

The next day Che and Leon were together cutting sugar cane in the fields. In the middle of this backbreaking work, Leon saw a big black car slowly advancing across the field. He turned to Che: “Comandante, it looks like you have a visitor,” he said. Che looked up, surprised and saw the limousine. Then his face lit up with a smile and he said to Leon: “Now just you watch this!”

The car came to a halt and a sweating official with a suit and tie stepped out and began to walk towards Che. Before he could open his mouth, Che shouted at him: “What are you doing here? Get out! We don’t want any bureaucrats here!” The shamefaced functionary turned back and headed for the car and Che turned to Leon: “You see!” he said with a triumphant grin.

When the Cuban Trotskyists were arrested Che personally intervened to secure their release. (He later said that this had been a mistake.) He also proposed a study of the writings of Leon Trotsky, who he regarded as one of the unorthodox Marxists. This attitude is very different to the position of the followers of Mao Tse Tung who described Trotsky as a counterrevolutionary and enemy of socialism.

These ideas are expressed in the letter of Che Guevara to Armando Hart Dávalos, which was published in Cuba in September, 1997 in Contracorriente, N°9. The letter was written in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania on 4 December 1965, during Che’s African expedition. In it he expresses himself in very critical terms on Soviet philosophy and the servile tail-endism of some Cubans:

“In this long period of holidays [sic!] I have stuck my nose into philosophy, which is something I have been meaning to do for a long time. I met my first difficulties in Cuba [where] there is nothing published except the unreadable Soviet tomes [literally “Soviet bricks” los ladrillos soviéticos] which have the drawback that they do not allow you to think, since the Party has done it for you and you just have to swallow it. As a method, this is completely anti-Marxist, and furthermore they are mostly very bad.”

“If you take a look at the publications [in Cuba] you will see a profusion of Soviet and French authors [He is referring to the French hard-line Stalinists like Garaudy]. This is due to the ease with which translations are obtained and also to ideological tail-endism [seguidismo ideológico]. This is not the way to give Marxist culture to the people. In the best case it is Marxist propaganda [divulgación marxista], which is necessary, if it is of good quality (which is not the case), but insufficient.”

He proposes an extensive plan of political education including the study of the collected works of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin “and other great Marxists. Nobody has read anything of Rosa Luxemburg, for example, who made mistakes in her criticism of Marx, but who died, assassinated, and the instinct of imperialism is superior to ours in cases like this. Also missing are Marxists who later went off the rails, like Kautsky and Hilfering (it is not written like that) [Che was thinking of the Austrian Marxist Rudolf Hilferding] who made some contributions, and many contemporary Marxists, who are not totally scholastic”.

He adds playfully: “and your friend Trotsky, who existed and wrote, so it seems, should be included.” His interest in Trotsky’s ideas increased in the same degree that he became disillusioned with the bureaucratic regimes of Russia and Eastern Europe. Che Guevara was an avid reader and he took many books with him on his last campaign in Bolivia. Among these, significantly, were books by Trotsky – the Permanent Revolution and the History of the Russian Revolution.

Given the extremely difficult conditions of guerrilla war in the mountains and jungles, a fighter will only take what he regards as absolutely necessary. This tells us a lot of how Che was thinking at this time. We have no doubt that had he lived he would have moved towards Trotskyism and in fact he was already doing so before his life was cut short.

Che Guevara was a dedicated revolutionary and Communist. He was also an internationalist and understood that to defend the Cuban revolution it was necessary to spread it to other parts of the world. He attempted this in Africa and Latin America. This was his strong side. His weak side was that he saw the revolution fundamentally as a peasant guerilla struggle and did not fully understand the central role of the working class in the socialist revolution.

The campaign against Che

The anniversary of the assassination of Che Guevara has been the signal for a noisy campaign against him. The attacks against Che do not all come from the right. There are constant attacks from anarchists, libertarians, and all kinds of “democrats”. Particularly distasteful are the criticisms of Che by Regis Debray, that miserable renegade and coward, who played such a pernicious role in Che’s last campaign in Bolivia and later became a reformist and an adviser to Mitterand.

The anniversary of the assassination of Che Guevara has been the signal for a noisy campaign against him. The attacks against Che do not all come from the right. There are constant attacks from anarchists, libertarians, and all kinds of “democrats”. Particularly distasteful are the criticisms of Che by Regis Debray, that miserable renegade and coward, who played such a pernicious role in Che’s last campaign in Bolivia and later became a reformist and an adviser to Mitterand.

Other “intellectuals” like Jon Lee Anderson, who wrote a well-known book about Che, Jorge Castaneda and Octavio Paz have joined this chorus of scoundrels and renegades vying with each other to “demystify” Che – that is, to pour dirt on his memory. This disgraceful campaign of calumnies has been backed by many in the Latin American “left”, which is just another indication of the degeneration of the “democratic” intelligentsia in the period of the senile decay of capitalism.

Writer Paul Berman informs us that the “modern-day cult of Che” obscures the work of dissidents and what he believes is a “tremendous social struggle” currently taking place in Cuba. There is indeed a tremendous social struggle taking place in Cuba. It is a struggle between revolution and counterrevolution: a struggle between those who wish to defend the gains of the Cuban Revolution and those who, under the false flag of “democracy” wish to drag Cuba towards capitalist slavery, as has already happened in Russia. In this struggle it is not possible to be neutral, and these “democratic intellectuals” have openly taken the side of the capitalist counterrevolution.

Another one of these scoundrels, author Christopher Hitchens, once considered himself a socialist and a supporter of the Cuban revolution, but now, like so many others of the middle class fair weather friends of Cuba has changed his mind. Of Che Guevara’s legacy he writes: “Che’s iconic status was assured because he failed. His story was one of defeat and isolation, and that’s why it is so seductive. Had he lived, the myth of Che would have long since died.”

No, my friend, Che Guevara is not dead but very much alive, and he will be remembered long after all this miserable tribe of bourgeois Pharisees has been forgotten. Yes, Che was defeated. But at least he had the courage to try to fight, and it is a thousand times better to try to fight and to fall honourably in battle for a just cause than to chatter and complain and whimper from the sidelines of history and to do precisely nothing.

The question of revolutionary violence

The main accusation against Che is that he was responsible for unnecessarily brutal repression. What are the facts? After the overthrow, Che Guevara was assigned the role of “supreme prosecutor”, overseeing the trials and executions of hundreds of suspected war criminals from the previous regime. As commander of the La Cabana prison, he oversaw the trial and execution of former Batista regime officials and members of the “Bureau for the Repression of Communist Activities” (a unit of the secret police known by its Spanish acronym BRAC). This has provided the excuse for a stream of vicious attacks against him by the enemies of the Revolution. We have seen a stream of articles with titles referring to Che as a “butcher” and so on.

In his book on Che, Jon Lee Anderson writes:

“Throughout January, suspected war criminals were being captured and brought to La Cabana daily. For the most part, these were not the top henchmen of the ancien régime; most had escaped before the rebels assumed control of the city and halted outgoing air and sea traffic, or remained holed up in embassies. Most of those left behind were deputies, or rank and file chivatos and police torturers. The trials began at eight or nine in the evening, and, more often than not, a verdict was reached by two or three in the morning. Duque de Estrada, whose job it was to gather evidence, take testimonies, and prepare the trials, also sat with Che, the “supreme prosecutor,” on the appellate bench, where Che made the final decision on the men’s fate.” (Source: Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, New York: 1997, Grove Press, pp. 386-387.)

José Vilasuso, an attorney who worked under Guevara, has said that these were “lawless proceedings” where “the facts were judged without any consideration to general juridical principles”. Vilasuso described a process where “[t]he statements of the investigating officer constituted irrefutable proof of wrongdoing” and where “[t]here were relatives of victims of the previous regime who were put in charge of judging the accused.”

Solon the Great, who wrote the Athenian Constitution and knew one or two things about laws, said the following: “the law is like a spider’s web: the small are caught and the great tear it up.” The law has never been higher than the class interests that lie behind it. The bourgeoisie hides behind the so-called impartiality of the law to disguise the dictatorship of the big banks and monopolies. When it no longer suits the ruling class, it sets aside these laws and exercises its dictatorship openly.

The people who were executed in La Cabana, were, as the above quotation says, notorious supporters of the Batista dictatorship that tortured and killed many people without trial, informers who spied on people and were responsible for their imprisonment, torture and death, and the torturers themselves. These were the people who were handed over to the revolutionary firing squads. And we are supposed to raise our hands in horror over this? Are we supposed to be shocked when the Revolution settles accounts with its enemies?

The same middle class Pharisees who whimper about these executions are those who support “peace and reconciliation” in places like Chile, Argentina and South Africa. They are the authors of the obscene farce of “truth commissions” where the murderers and torturers meet face to face with their victims, with widows and orphans, with people who suffered unspeakable tortures or years of imprisonment for their views. And at the end of this, they are supposed to be reconciled and “at peace”. Yes, and how many others are “at peace” in unmarked graves or at the bottom of the River Plate with their hands chopped off?

This so-called peace and reconciliation is nothing but a cruel deception and the so-called truth commissions a cowardly evasion of the truth: that there can never be peace and reconciliation between the murderers and torturers and their victims, who cry for justice even from the grave. It is absolutely intolerable that today known murderers and torturers walk the streets of Santiago, Buenos Aires and Johannesburg, and their victims are forced to live with this knowledge. In Spain the reformists and Stalinists subscribed to the shameful fraud that they called the “Transition”. The fascist butchers who were responsible for the deaths of over a million people were allowed to go unpunished as a result. This was taken by the reformists in Chile and elsewhere to be a good example to follow.

Was it a good thing that Pinochet was permitted to die peacefully in his bed of old age? Would it not have been better for this mass murderer to be tried by the families of his victims? A violation of the principles of legality, say the Pharisees! An act of true revolutionary justice, we reply! To preach love and reconciliation in the midst of the class struggle is a form of crime: for it is always the weak and defenceless who are expected to show love and forgiveness, while the rich and powerful always escape the consequences of their crimes.

Che Guevara was a humanitarian who had a deep love for the poor and oppressed, and consequently he had a profound hatred for the oppressors and exploiters. He wrote:

“Hatred is an element of struggle; relentless hatred of the enemy that impels us over and beyond the natural limitations of man and transforms us into effective, violent, selective, and cold killing machines. Our soldiers must be thus; a people without hatred cannot vanquish a brutal enemy.”

Harsh words? Yes, but the class struggle is harsh, and the consequences of defeat are deadly serious. Cuba is only 90 miles from the most powerful imperialist nation on earth. Not long after these events US imperialism organized an invasion with the help of those agents of Batista who Che did not manage to place before a firing squad.

Hypocrisy of imperialists

The attacks of the enemies of the Revolution are motivated by spite and hypocrisy. A Revolution has to defend itself against its enemies, both internal and external. A Revolution, which by its very nature overturns all the old laws, rules and regulations cannot be expected to operate on the basis of bourgeois legality. It has to invent new rules and a new legality and the only rule it knows is the one invented long ago by Cicero: salus populi suprema lex est (the salvation of the people is the supreme law). For revolutionaries the salvation of the revolution is the supreme law. The idea that a revolution must dance the minuet of bourgeois legality is just stupidity.

Throughout history there have been many risings of the oppressed underdogs against their masters. The annals of human history are full rich in defeated slave rebellions and similar tragedies. In every case we find that the slaves were defeated because they did not show sufficient determination and were too soft and trusting, whereas the ruling class is always prepared to employ the most brutal and bloody methods in order to maintain their class rule.

History is full of examples of the brutality of the ruling class. After the defeat of Spartacus, the Romans crucified thousands of slaves along the Via Apia. In June, 1848, general Cavaignac had promised pardon, and he massacred the workers. The bourgeois Thiers had sworn by the law, and he gave the army carte-blanche to slaughter. After the defeat of the Commune, the butchers of Versailles took a terrible revenge against the proletarians of Paris. Lissagaray (History of the Paris Commune of 1871) writes:

“The wholesale massacres lasted up to the first days of June, and the summary executions up to the middle of that month. For a long time mysterious dramas were enacted in the Bois de Boulogne. Never will the exact number of the victims of the Bloody Week be known. The chief of military justice admitted 17,000 shot, the municipal council of Paris paid the expenses of burial of 17,000 corpses; but a great number were killed out of Paris or burnt. There is no exaggeration in saying 20,000 at least.

“Many battlefields have numbered more dead, but these at least had fallen in the fury of the combat. The century has not witnessed such a slaughtering after the battle; there is nothing to equal it in the history of our civil struggles. St. Bartholomew’s Day, June 1848, the 2nd December, would form but an episode of the massacres of May. Even the great executioners of Rome and modern times pale before the Duke of Magenta. The hecatombs of the Asiatic victors, the fetes of Dahomey alone could give some idea of this butchery of proletarians.”

There are many more recent examples. After the overthrow of the democratically elected Arbenz government, the rulers of Guatemala unleashed a bloody war of genocide against its own people with the aid of the CIA. Pinochet killed and tortured tens of thousands. In Argentina there was even greater slaughter under the Junta. In the case of Cuba, the American stooge Batista murdered and tortured countless oppositionists.

All this is a matter of historical record. The so-called democrats in the USA and the European Union pretend to be shocked at the revolutionary violence which the Cuban Revolution directed against its enemies, but the same people were prepared to turn a blind eye to the crimes of the counterrevolutionary despots who were the friends of US imperialism. As President Franklin D Roosevelt said about the Nicaraguan dictator Somoza: “He’s a son of a bitch, but he’s our son of a bitch.”

The Bay of Pigs

The bourgeois approach the question of violence from a practical and class point of view. The working class should do likewise. The idea that it is possible to defeat the class enemy by reading them lectures on morality is naïve and foolish. The real reason for the hypocritical cries of moral outrage against the Cuban (and Russian) Revolutions is that here at last the slaves fought back against the slave-owners, and they won.

In the beginning, Castro did not put forward a socialist perspective and did not nationalize anything. Che, on the other hand, insisted that the Cuban Revolution must be a socialist revolution. The Revolution soon entered into conflict with US imperialism, which attempted to sabotage its attempts to carry out an agrarian reform and other measures to improve the living standards of the masses. The big US companies tried to sabotage the Cuban economy. Castro responded by nationalizing all US property in Cuba. The Revolution had crossed the Rubicon. It had expropriated the landlords and capitalists and was now on collision course with Washington.

This was a complete confirmation of Trotsky’s theory of Permanent Revolution – a theory that Che was so interested in that he took a copy of this book with him on his final Bolivian expedition. Trotsky explains that in modern conditions the tasks of the bourgeois democratic revolution in colonial and ex-colonial countries cannot be carried out by the bourgeoisie but can only be realized by expropriating the landlords and capitalists and beginning the socialist transformation of society.

The imperialist “democrats” replied by organizing an invasion of Cuba. Cuban mercenaries were armed and trained by the CIA and set out to effect the violent overthrow of the revolutionary government. The Revolution defended itself, mobilizing and arming the workers and peasants. The imperialist forces were routed at the Bay of Pigs – the first time that imperialism had suffered a military defeat in Latin America. The Revolution was triumphant.

If the reactionaries had succeeded in regaining power, what would they have done? Would they have invited the Cuban workers and peasants to join them in a universal celebration of brotherly love and reconciliation? Would they have set up a truth commission and invited Che and Fidel to participate? They would have filled not one Cabana but a hundred with their victims. Only a blind man can fail to understand this. But there are none so blind as they who will not see.

Che and world revolution

The Cuban Revolution was in danger. How was it to be saved? Che Guevara had the right idea, and was moving in the right direction before his young life was brutally ended. He was radically opposed to bureaucracy, corruption and privilege, which are today the biggest threat to the Cuban Revolution and, if not corrected, will prepare the way for capitalist restoration. Above all, he understood that the only way to preserve the Cuban Revolution was to extend the socialist revolution to the rest of the world, beginning with Latin America.

His speeches against bureaucracy and his criticisms of the Soviet Union became more and more outspoken to the degree that the influence of the Soviet Union in Cuba grew. In general he had grown increasingly sceptical of the Soviet Union. He publicly accused Moscow of betraying the colonial revolution. In February 1965 Che made what turned out to be his last public appearance on the international stage when he delivered a speech to the Second Economic Seminar on Afro-Asian Solidarity in Algiers. In the course of his speech he stated:

“There are no frontiers in this struggle to the death. We cannot remain indifferent in the face of what occurs in any part of the world. A victory for any country against imperialism is our victory, just as any country’s defeat is our defeat.” He went on to say that, “The socialist countries have the moral duty of liquidating their tacit complicity with the exploiting countries of the West.”

This was a very explicit condemnation of the policy of peaceful co-existence pursued by Moscow. He considered that the withdrawal of Soviet missiles from Cuban territory without consulting Castro to be a betrayal. He enthusiastically supported the Vietnamese people in their war of liberation against US imperialism. He called upon the oppressed peoples of other countries to take up arms and create “100 Vietnams”. Such talk horrified Khrushchev and the Moscow bureaucracy.

In his mind the idea slowly matured that the only way to save the Cuban Revolution was to spread the revolution on a world scale. This idea was fundamentally correct. The isolation of the Cuban Revolution was the greatest threat to its survival. Che was not a man to allow an idea to remain on paper. He decided to translate it into action. Che Guevara left Cuba in 1965 to participate in the revolutionary struggles in Africa. He first went to Congo-Kinshasa, although his whereabouts remained a closely held secret for the next two years.

Che wrote a letter in which he reaffirmed his solidarity with the Cuban Revolution but declared his intention to leave Cuba to fight abroad for the cause of the revolution. He stated that “Other nations of the world summon my modest efforts,” and that he had therefore decided to go and fight as a guerrilla “on new battlefields”. In order not to embarrass the Cuban government and provide excuses to the imperialists to attack Cuba, he announced his resignation from all his positions in the government, in the Party, and in the Armed forces, and renounced his Cuban citizenship, which had been granted to him in 1959 in recognition of his efforts on behalf of the revolution.

“This is the history of a failure.”

At that time Africa was in a state of ferment. The French colonialists had been driven out of Algeria and the Belgian imperialists had been forced to leave the Congo. But the imperialists were waging a stubborn rearguard action in alliance with the Apartheid regime in South Africa and reactionary elements in different countries. At stake was Africa’s vast mineral wealth. It was also the chief battleground between the Soviet Union and the United States.

Che concluded that this was the best place to fight. Ben Bella, who was president of Algeria, had recently held discussions with Guevara, and said: “The situation prevailing in Africa, which seemed to have enormous revolutionary potential, led Che to the conclusion that Africa was imperialism’s weak link. It was to Africa that he now decided to devote his efforts.”

In the recently independent Congo the Belgian and French imperialists sabotaged the left-wing government of Patrice Lumumba by creating chaos as a pretext for a military intervention. With the active collaboration of the CIA the reactionaries led by Mobutu murdered Lumumba and seized power in Leopoldville (Kinshasa). A guerrilla war led by Lumumba supporters commenced. The Cuban operation was to be carried out in support of the rebels under the command of Laurent-Désiré Kabila.

Astonishingly, the thirty-seven year old Guevara had no formal military training (his asthma had prevented him from being drafted into military service in Argentina) but he had the experiences of the Cuban revolution, and that was enough. In the same way, Trotsky had no formal military training when he formed the Red Army, yet the Red soldiers, armed by revolutionary fervour, defeated every foreign army thrown against them.

Napoleon pointed out long ago that in warfare morale is always the decisive factor. However, Che was swiftly disillusioned by his Congolese allies. He had little regard for the ability of Kabila. “Nothing leads me to believe he is the man of the hour,” he wrote. The Cuban and Russian revolutionaries were fighting for a cause they believed in. But in the Congo, the anti-imperialist struggle was mixed up with tribal divisions, personal ambition and corruption. That was shown by subsequent events. In May 1997, Laurent Kabila overthrew Mobuto and became President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In that position, which he held until his assassination in 2001, he behaved as a corrupt tyrant. He was succeeded in the presidency by his son, the equally corrupt Joseph Kabila.

The CIA and South African mercenaries were working with Mobutu’s forces to defeat the rebels. They soon realized that they were fighting a far more serious enemy, although originally they did not know that Che was present. However, the superior intelligence available to the CIA alerted the South Africans to his presence. Che’s Congo Diary speaks of the incompetence, stupidity, and infighting of the local Congolese forces. This was the main reason for the revolt’s failure. Without Cuban help it would have been defeated much earlier.

After seven months of frustrations, suffering from his asthma and crippling dysentery and disillusioned with his allies, Che left the Congo with the surviving members of his force of Afro-Cubans. Later, when writing of the Congo mission, he states bitterly: “This is the history of a failure.”

Bolivia

After the failure in Africa, Che decided to attempt to open a new revolutionary front in Latin America. He seems to have chosen Bolivia for its strategic position, bordering a number of important countries, including Argentina. He adopted the disguise of a Uruguayan businessman with thick glasses and a shaved head. This was so perfect that when he said his final goodbye to his little daughter she did not recognize him. However, the imperialists were not so easily fooled.

Che clearly made a mistake when he tried to organize a guerrilla war in Bolivia, a country with a powerful working class with great revolutionary traditions. He miscalculated in a number of areas. He expected to be confronted only by the poorly trained and equipped Bolivian army. But, as we have already pointed out, the imperialists had learned the lesson of Cuba and were prepared for him. Only eleven months after beginning the operation the guerrillas were routed and Che Guevara was dead. Only five men managed to escape from the trap that had been prepared for them by the Bolivian army and its US “advisers”.

To read today Che Guevara’s Bolivian Diaries is a moving and tragic experience. The physical and mental sufferings of this small band of men are indescribable. Their final destiny is heartbreaking. He established his base in the jungles of the remote Ñancahuazú region. But building a guerrilla army under such conditions proved extremely difficult, as his Bolivian diary shows. But to start a revolution in the jungles of Bolivia, was a hopeless venture from the start. The total guerrilla force numbered only about fifty. They experienced great difficulty recruiting from the local populace, who did not even speak Spanish. The guerrillas had learned Quechua, but the local language was Tupí-Guaraní.

Despite everything, the guerrillas showed tremendous bravery and determination and scored a number of early successes against Bolivian regular soldiers in the Camiri mountains. However, in September, the Army managed to eliminate two guerrilla groups, killing one of the leaders. From this point on, they were fighting a battle that was lost in advance. Moreover, as the campaign dragged on, Che’s health deteriorated. He suffered from severe and debilitating bouts of asthma.

The Bolivian authorities were finally alerted about Guevara’s presence when photographs taken by the rebels fell into their hands after a clash with the Bolivian army in March 1967. It is said that after seeing them, President René Barrientos exclaimed that he wanted Guevara’s head on a pike in the centre of la Paz. Here we have an authentic expression of the humanitarian pacifism of the bourgeoisie – the same people who criticize revolutionaries for violence.

Despite the attempts to portray him as a bloodthirsty monster (what revolutionary leader has not been so portrayed?) Che was actually a very humanitarian person. In one very moving passage of his Bolivian Diaries he recalls a moment when he could have shot a young Bolivian soldier but found himself unable to pull the trigger.

This is hardly the conduct of a cruel and bloodthirsty man! Che personally gave medical treatment to wounded Bolivian soldiers whom the guerrillas took prisoner, and then let them go free. This humane behaviour contrasts to the brutal treatment he himself received when he fell into the hands of the Bolivian army. It is even said that, when captured, he offered to treat some Bolivian soldiers who had also been wounded in the fighting. The Bolivian officer in charge rejected his offer.

Stalinists betray

Che’s men faced innumerable obstacles – not only from the language and the weather (it was almost always raining) and the terrain. Under the Stalinist pro-Moscow leadership of Mario Monje the Bolivian Communist Party was bitterly hostile to Guevara and resented his presence in Bolivia. The Bolivian Stalinists refused to honour their commitments to the guerrillas. They argued that there were no conditions to launch a revolutionary offensive in Bolivia. Fidel Castro in his Introduction to Che’s Bolivian Diaries answered this very well:

“There will always be a proliferation of excuses, whatever the time and circumstance, not to fight – and that would mean that we could never obtain freedom. Che did not outlive his ideas, but he knew that with the loss of his life they would spread even wider. His pseudo-revolutionary critics, with their political cowardice and eternal failure to act, will certainly outlive the evidence of their own stupidity. It is worth noting, as the diary shows us, that Mario Monje, one of those ‘revolutionary’ specimens who are becoming so frequent in Latin America, took advantage of his title of secretary of the Communist Party of Bolivia to dispute Che’s right to the political and military leadership of the movement. And Monje had also announced his intention of giving up his position within the party. According to him, it was enough to have held the position, and that gave him the right to claim the leadership.

“Mario Monje, needless to say, had no experience in guerrilla warfare, nor had he ever been in combat. But the fact that he considered himself a Communist should have rid him of crude and superficial patriotism, as had the true patriots who had fought for Bolivia’s first independence.

“If this is their idea of the internationalist and anti-imperialist struggle on this continent, such ‘Communist leaders’ have not progressed as far as the aboriginal tribes who were vanquished by the European colonisers at the time of the conquest.

“This was the behaviour of the leader of the Communist Party of a country called Bolivia, whose historical capital is called Sucre, in honour of its first liberators, who were both Venezuelan. Monje had the opportunity to count on the co-operation of the political, organisational and military talent of a true and revolutionary giant, whose cause was not circumscribed to the narrow, artificial and even unjust boundaries of Bolivia. However, Monje did nothing but make claims for the leadership in a shameful, ridiculous and unwarranted manner.” (Ernesto Che Guevara, Bolivian Diary, “A Necessary Introduction” by Fidel Castro, pp. xxxi-xxxii.)

And Castro continues his blistering indictment of Monje and the leaders of the Bolivian C.P.:

“[…] But Monje, unhappy with the outcome, set out to sabotage the movement. While in La Paz, he intercepted the well-trained Communist militants who were about to join the guerrilla force. They were the kind of men who have all the necessary qualities to join the armed struggle, but whose progress is criminally frustrated by their incapable and manipulating leaders.” (Ernesto Che Guevara, Bolivian Diary, “A Necessary Introduction” by Fidel Castro, p. xxxiii.)

At the end of January, Che wrote in his Diary:

“Analysis of the month.

“As I expected, Monje’s attitude was evasive at first and then treacherous.

“The party is now up in arms against us, and I do not know how far they will go. But this will not stop us and maybe in the long run it will be to our advantage (I am almost certain of this). The most honest and militant people will be with us, even if they have to go through a crisis of conscience that may be quite serious.

“Moisés Guevara has so far responded well. We shall see how he and his people behave in the future.

“Tania left, but the Argentines have given no signs of life, and neither has she. Now begins the real guerrilla phase and we will test the troops. Time will tell what they are capable of and what are the prospects for the Bolivian revolution.

“Of all we had envisaged, the hardest task was the recruitment of Bolivian combatants.” (Ernesto Che Guevara, Bolivian Diary, p. 38.)

Those members of the Party who did join or support Che Guevara did so against the Party leadership’s wishes. Che’s Bolivian Diary shows how the problems with the Bolivian Communist Party resulted in the guerrillas having significantly smaller forces than originally anticipated. This dealt a mortal blow to the guerrilla’s chances of success.

Regis Debray

A lamentable role in all this was played by Regis Debray, a man who subsequently made a career out of exploiting his alleged relation with Che Guevara. It is frequently stated that he “fought with Che in Bolivia” and was a “comrade of Che.” This is completely untrue. Debray never did any fighting and in fact caused serious problems for the guerrillas. Che regarded this petty bourgeois intellectual with well-deserved contempt. His Diary contains frequent references to this unwelcome “travelling companion” and none of them is flattering.

Debray and the Argentine painter Ciro Bustos turned up in Che’s camp as revolutionary tourists and caused nothing but trouble. They were supposed to help to develop contacts with the outside world. In the end they got plenty of publicity for themselves at the cost of the guerrillas. The Diary shows that Che was suspicious of Debray from the start:

“The Frenchman emphasised rather too vehemently how useful he could be outside.” (Ernesto Che Guevara, Bolivian Diary, p. 69.)

Che’s suspicions were soon justified. Unable to tolerate the harsh conditions they pestered Che to allow them to leave. They were soon captured by the army and gave information that was invaluable in the pursuit of the rebels. Bustos betrayed the guerrillas and became a vulgar informant. He even drew portraits so that the army could recognize them. The trial of Regis Debray attracted the attention of the world’s media, but distracted attention from the guerrillas who were the ones really putting up a fight. This trial undoubtedly embarrassed the Bolivian government, but it also hardened their attitudes towards the guerrillas. It is possible that one of the reasons Barrientos decided to murder Guevara was to avoid a repetition of the media circus of this trial.

The final chapter

Barrientos ordered the Bolivian Army to hunt Guevara down. But in fact he was merely following the orders of his bosses in Washington, who had long ago put a price on the head of their most hated enemy. As soon as Washington discovered his location, CIA and other special forces were sent to Bolivia, where they took charge of the operation.

Barrientos ordered the Bolivian Army to hunt Guevara down. But in fact he was merely following the orders of his bosses in Washington, who had long ago put a price on the head of their most hated enemy. As soon as Washington discovered his location, CIA and other special forces were sent to Bolivia, where they took charge of the operation.

US advisors arrived on April 29 and instituted a 19-week counter-insurgency training programme for the Bolivian 2nd Ranger Battalion. The intensive course included training in weapons, individual combat, squad and platoon tactics, patrolling, and counter-insurgency. The Bolivian Army was trained and supplied by US advisors and Special Forces. These included a recently established elite battalion of Rangers with special training in jungle operations.

From late September the enemy dogged their footsteps. Bolivian Special Forces were notified of the location of Guevara’s guerrilla encampment by an informant. They encircled it on 8 October and Che was captured after a brief skirmish. As the Bolivian forces approached him, he is supposed to have called out: “Do not shoot! I am Che Guevara and worth more to you alive than dead.” By this means they try to portray him as a coward. This is just another of the calumnies with which the reactionaries attempt to blacken the memory of this man, who always showed great bravery and complete disregard for his personal safety.

Barrientos lost no time in ordering the execution of Che Guevara. He issued the order as soon as he was informed of the capture. He did not waste time in legal niceties. He did this with the full knowledge and consent of the “democrats” in Washington. None of these people could run the risk of a trial where Che Guevara could defend himself and, as he inevitably would, pass over to the counteroffensive, denouncing the social injustices that justified his fight. No! This voice had to be silenced once and for all.

In January 1919 in Berlin, the Junkers who captured Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht also had no intention of allowing them to reach a court of law. They did not consult a law book before battering their brains out either. Che Guevara was taken to a dilapidated schoolhouse in the nearby village of La Higuera where he was held prisoner overnight. What thoughts must have gone through his mind on that last terrible night when he was alone, like a lamb among hungry wolves, alone and isolated from the world, from his family, friends and comrades, facing dawn and inevitable death!

Early the next afternoon Che Guevara was taken out of the schoolhouse. At 1.10pm on 9 October 1967 he was executed by Mario Teran, a sergeant in the Bolivian army. In an attempt to conceal the fact that he had been shot in cold blood, he received multiple shots to the legs, so as to simulate combat wounds. Before this he said to his executioner: “I know you are here to kill me. Shoot, coward, you are only going to kill a man.” This is the voice of the real Che Guevara, not that of a coward pleading for his life.

The dead body was lashed to the landing skids of a helicopter and flown to neighbouring Vallegrande where it was placed in a laundry tub in the local hospital and put on display for the gentlemen of the press who took photographs. In a macabre act of desecration a military doctor surgically amputated his hands, Bolivian army officers transferred Guevara’s cadaver to an undisclosed location.

The man who headed the hunt for Guevara was Felix Rodriguez, a CIA agent, who had infiltrated Cuba to prepare for an anti-Castro uprising to coincide with the Bay of Pigs invasion. It was Rodriguez who informed his masters in Washington and Virginia of Che’s death. Like a common thief he removed Che’s Rolex watch and other personal items that he used to show to reporters while bragging of his exploits. Felix Rodriguez’s name will enter the annals of history branded with infamy. But the memory of the man he cruelly murdered will forever live as a champion of the poor and oppressed, a fighter, a revolutionary hero and a martyr for the cause of world socialism.

The question of guerrilla war

As with any other person, Che had his strong side and his weak side. He undoubtedly made a mistake when he attempted to present the Cuban model of guerrilla war as a tactic with a general application. Marxists have always conceived the peasant war as an auxiliary of the workers in the struggle for power. That position was first developed by Marx during the German revolution of 1848, when he argued that the German revolution could only triumph as a second edition of the Peasants’ War. That is to say, the movement of the workers in the towns would have to draw behind it the peasant masses.

It is not correct to argue that this position is only for developed capitalist countries. Before the Russian revolution the industrial working class represented no more than 10 per cent of the population. Yet Lenin and the Bolsheviks always argued that the working class had to place itself at the head of the nation and lead the peasants and other oppressed layers behind them. The proletariat played the leading role in the Russian revolution, drawing behind itself the multi-millioned mass of poor peasants – the natural ally of the proletariat.

The only class able to lead a successful socialist revolution is the working class. This is not for sentimental reasons but because of the place it occupies in society and the collective character of its role in production. No reference or hint at the possibility that the peasantry can bring about a socialist revolution can be found in the writings of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Trotsky. The reason for that is the extreme heterogeneity of the peasantry as a class. It is divided into many layers, from the landless labourers (who are really rural proletarians) to the rich peasants who employ other peasants as wage labourers. They do not have a common interest and therefore cannot play an independent role in society. Historically they have supported different classes or groups in the cities.

By its very nature, guerrilla warfare is the classical weapon of the peasantry, and not the working class. It is suited for conditions of armed struggle in inaccessible rural areas – mountains, jungle, etc. – where the difficulty of the terrain makes it complicated to deploy regular troops and where the support of the rural masses provides the necessary logistic support and cover for the guerrillas to operate.

In the course of a revolution in a backward country with a sizeable peasant population, guerrilla warfare can act as a useful auxiliary for the revolutionary struggle of the workers in the towns. But it would never have occurred to Lenin to put forward the idea of guerrillaism as a substitute for the conscious movement of the working class. Guerrilla tactics, from a Marxist standpoint, are only permissible as a subordinate and auxiliary part of the socialist revolution.

This was precisely Lenin’s position in 1905. It had nothing in common with the kind of individual terrorist tactics pursued by the Narodnaya Volya and their heirs, the Social Revolutionary Party, still less the insane tactics of the modern terrorists and “urban guerrilla” organisations which are the very antithesis of a genuine Leninist policy. Lenin insisted that armed struggle must be part of the revolutionary mass movement, and specified the conditions in which it was permissible:

“1) the sentiments of the masses be taken into account; 2) the conditions of the working class movement in the given locality be reckoned with, and 3) care be taken that the forces of the proletariat should not be frittered away.” And he also made it clear that, far from being a panacea, guerrilla war was only one possible method of struggle permissible only “at a time when the mass movement has actually reached the point of an uprising”.

The danger of degeneration inherent in such activity becomes an absolute certainty the moment the guerrilla groups are isolated from the mass movement. In the period following 1906, when the workers’ movement was in decline and the revolutionaries were reeling from a series of body blows, the guerrilla organizations increasingly displayed signs that they were ceasing to be useful auxiliary organs of the revolutionary party, and becoming transformed into groups of adventurers, or even worse. Even while defending the possibility of guerrilla tactics as a kind of rearguard action against reaction at a moment when he still expected the revolutionary movement to revive, Lenin warned against “anarchism, Blanquism, the old terrorism, the acts of individuals isolated from the masses, which demoralize the workers, repel wide strata of the population, disorganise the movement and injure the revolution,” and added that “examples in support of this appraisal can easily be found in the events reported every day in the newspapers”.

In the period 1905-06, the revolutionary movement included an element of “guerrilla warfare”, with partisan detachments, armed expropriation, and other forms of armed struggle. But the fighting squads were always closely linked to the workers’ organizations. Thus, the Moscow military committee included not just RSDLP members, but also SRs, trade unionists (printers) and students. As we have seen, partisan groups were used for the purpose of defence against pogromists and the Black Hundred gangs. They also helped to protect meetings against police raids, where the presence of armed workers’ detachments was frequently an important factor in preventing violence.

Other tasks included the capture of arms, the assassination of spies and police agents and also bank raids for funds. The initiative for the setting up of such guerrilla groups was frequently taken by the workers themselves. The Bolsheviks strove to gain the leadership of these groups, to give them an organized and disciplined form and provide them with a clear plan of action. There were, of course, serious risks entailed here. All kinds of adventurist, declassed and shady elements could get mixed up in these groups, which, once isolated from the movement of the masses, tended to degenerate along criminal lines to the point where they would become indistinguishable from mere groups of bandits.

In addition to this, they were also wide open to penetration by provocateurs. As a rule it is far easier for the agents of the state to infiltrate militaristic and terrorist organizations than genuine revolutionary parties, especially where they are composed of educated cadres bound together by strong ideological ties, although even the latter are not immune to penetration. Lenin was well aware of the dangers of degeneration posed by the existence of the armed groups. Strict discipline and firm control by party organizations and experienced revolutionary cadres partially guarded against such tendencies. But the only real control was that of the revolutionary mass movement.

As long as the guerrilla units acted as auxiliaries to the mass movement (that is, in the course of the revolutionary upswing) they played a useful and progressive role. But, wherever the guerrilla groups were separated from the mass revolutionary movement, they inevitably tended to degenerate. For this reason, Lenin considered it completely inadmissible to prolong their existence, once it was clearly established that the revolutionary movement was in irreversible decline. Once this stage was reached, he immediately called for the dissolution of all the guerrilla groups.

Guerrilla warfare

Che wrote a number of articles and books on the theory and practice of guerrilla warfare. The experience of the overthrow of the Arbenz government made a lasting impression on him. He concluded that the ruling class must be overthrown by an armed insurrection, and that assumption was quite correct. All history shows that no ruling class has ever surrendered its power and privileges without a fight. No devil has ever cut off its own claws. Marxists are not pacifists. The masses must be prepared to fight and to use whatever force is necessary to disarm the ruling class. In the words of Marx, force is the midwife of history.