The pressure is piling up on the government as the Autumn Budget approaches. And the financial markets are turning the screw, with the price of government bonds jumping and falling in response to every new announcement by the Chancellor.

But what does all of this mean? What does the bond market have to do with tax rises or public sector cuts?

The complicated economic jargon used by the press to explain the state’s finances feels like it is designed to be as confusing as possible. But the reality is quite simple.

Governments sell bonds – known in Britain as ‘gilts’ – as a means of borrowing money. The higher the interest rates on gilts are, the more that the UK government has to pay its lenders in order to borrow money.

The interest rate (or ‘yield’) on 30-year gilts rose to a peak of 5.74 percent in September this year, from a previous level of around 4.5 percent this time last year. This is the highest rate since 1998. For the government, this is bad news arriving at a bad time.

Debt servicing already costs the Treasury more each year than is spent on housing and the environment (£44 billion) and social services (£51 billion) combined.

This year’s borrowing bill – money going straight from taxpayers’ wallets into the bankers’ pockets – stands at a staggering £126 billion.

Bond market rebellion

So why is the price of long-term government borrowing so high? In short, because of long-term doom and gloom surrounding the state of the public finances.

In the past, lending to the British government was considered a safe investment. Today, by contrast, investors are sceptical.

There is a perfect storm of contradictions combining and contributing to create this conundrum.

Firstly, stubborn inflation. This devalues loans over a long period of time. Lenders therefore want higher interest payments in order to offset the corrosive impact of inflation.

Secondly, the broader economic outlook is dire. The world economy is slowing down, and British capitalism’s position is weaker than ever.

Slow – or negative – growth means less economic activity, less profit, and less tax revenue. This puts into question the government’s ability to pay back its debts or interest further down the line.

Worried by this prospect, investors are selling their bonds for cheaper than they bought them. And when the price of bonds goes down, the corresponding interest rate (the yield) goes up. In order for the government to entice buyers for new bonds, it must offer higher interest rates, to match what is offered on the open market.

The government intended to sell around £300 billion worth of government bonds this year. At the latest rates, this would mean roughly £17 billion of extra interest to repay on just this year’s new debt, rather than £13.5 billion at last year’s rate.

This is on top of the over £100 billion that the Treasury already pays out in interest on previously accumulated borrowing.

These private investors, jettisoning the government bonds they hold, are often referred to as ‘bond vigilantes’. But they are just following the logic of the market.

The ruling class are not currently attempting to oust Starmer’s government, as they have no more reliable alternative to turn to. Rather, the markets are essentially holding the government to ransom – trying to impose austerity policies on them.

As the New Statesman put it: “Governments are now at the mercy of unseen investors.”

Parliamentary rebellion

This is where we see the political side of the bond markets. In return for their lending, the country’s creditors demand cuts and privatisation, and now tax hikes on ordinary workers.

The investors and hedge funds who buy UK bonds are losing confidence in the government’s ability to balance the books and meet their interest payments.

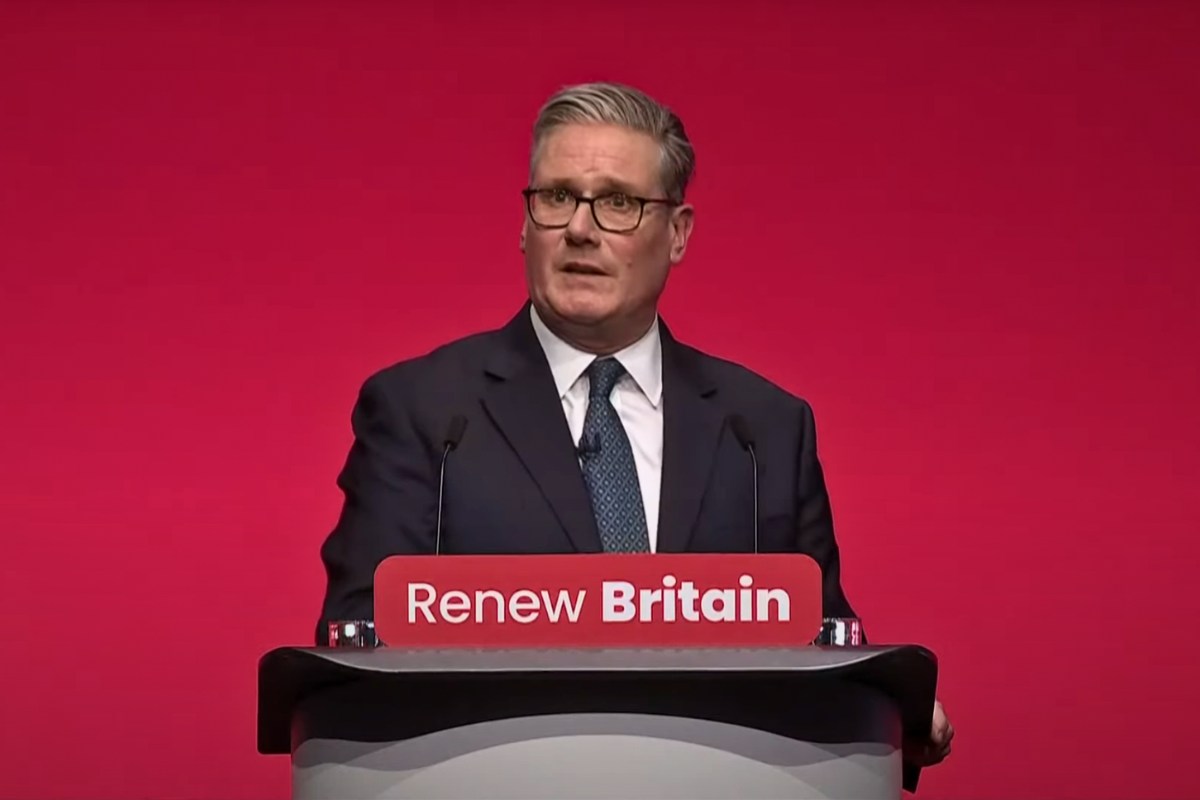

This follows Starmer and Reeves’ failed attempt at the beginning of July to pass a series of welfare cuts through Parliament. This extremely unpopular bill provoked a rebellion of Labour MPs, worried about the anger of their constituents. This produced the recent spike in borrowing costs.

Now, on the eve of the Autumn Budget, there is an estimated £30-40 billion ‘fiscal black hole’ to plug. The borrowing needed to fill this will cost more than ever.

Starmer’s popularity stands lower than any prime minister since records began. And backroom rumours of replacing him have made it onto the newspapers’ frontpages.

The careerist MPs that make up the Parliamentary Labour Party are worried about their jobs come the next election. Another deeply unpopular austerity budget could therefore provoke another backbench mutiny.

Despite having a huge majority in the House of Commons, then, Starmer’s government may struggle to push through the measures demanded by the capitalists.

This also explains Chancellor Rachel Reeves’ wavering and U-turns around potential tax increases that would fall on ordinary families.

All of this uncertainty enormously undermines the ruling class’ confidence that this government can be trusted to take the ‘tough decisions’ they deem necessary. Bond selloffs and increased borrowing costs are the response to all this.

UK government debt now sits at £2.9 trillion – and is growing every day. There has even been chatter of an IMF bailout for the UK in the boardrooms of the City of London. Brutal cuts are ‘required’. But the government may be unable to administer these.

What is government debt?

This is the stark reality facing the ruling class and its representatives. Yet the reformists seem to think that this wouldn’t apply to them; that these pressures are imaginary, and could simply be magicked away.

A recent Guardian editorial maintains the utopian position of Modern Monetary Theory, for example. This posits that the government – along with its central bank and ‘sovereign’, floating currency – has the power to “shape markets, not the other way round”.

“The UK can and should run fiscal deficits to fund a green industrial strategy – investing in domestic manufacturing, energy security, and a strong export base,” the article’s authors propose. “Investing in industrial capacity and public goods strengthens the economy, helps reduce inequalities and reduces vulnerability over time.”

These reformist illusions fly in the face of the real perspectives for British capitalism. The state cannot conjure economic activity and prosperity out of thin air.

Unfortunately, these remain the fantasies that left reformists base themselves on. This includes figures like Jeremy Corbyn and Green Party leader Zack Polanski.

We must be absolutely clear, however: this outlook is completely out of step with reality.

Borrowing may be all well and good when the system is healthy. Lenders are generally happy to lend as long as the interest payments keep flowing in, and the assets on their balance sheet keep growing.

When the system enters into crisis, however, growth stagnates, companies stop expanding, and lenders start calling in their loans. What goes up, must come down, as they say. And this is true for debt.

Debt is not a meaningless accounting trick. Nor is it imaginary or arbitrary. All debt is someone else’s property. The bonds that creditors hold represent their claim to a slice of future surplus value.

The class struggle is ultimately a struggle over the surplus in society. As Marx explained, in relation to government debt:

“[The] accumulation of money-capital and of money wealth in general…has resolved itself into an accumulation of claims of ownership upon labour. The accumulation of the capital of the national debt has been revealed to mean merely an increase in a class of state creditors, who have the privilege of a firm claim upon a certain portion of the tax revenue.” (Capital, Vol III, Chapter 30)

Class contradictions

On the other side, the pressure of the working class forces the ruling class to maintain certain living standards and social services.

Infrastructure, transport, hospitals, schools, care homes, local council services, benefits to the unemployed, pensions, and so on: all these things hold together the fabric of society. And if they are not properly provided, this fabric tears and unravels, leading to growing discontent.

These are the standards that the working class has established through generations of struggle; demands that are expected of the state and the capitalist system.

But these things cost a certain amount of money. And the state has few means for raising revenue via anything other than taxes.

In times of economic slump, in particular, capitalism cannot afford the conditions that the working class demands. Hence the objective pressure for austerity and attacks.

Unwilling and unable to tax the rich, lest they move their money and investment elsewhere, capitalist governments resort to borrowing from them instead. But all this does is delay the day of reckoning.

The ruling class, meanwhile, generally has a different view of how much the state should spend, and on what.

As Roger Bootle – the Chairman of Capital Economics, a financial advice company for investors in the City of London – wrote in the Telegraph back in March: “The idea that we cannot afford to increase defence spending is a sick joke. Take an axe to the welfare bill.”

This provides an insight into the psychology of the bourgeoisie. For them, the wealth produced by the working class should be hoarded as profit and spent in the interests of imperialism, not ‘wasted’ on welfare and public services.

Class war

Finance capital, then, holds the purse strings and dictates the tune to capitalist politicians. But passing the austerity budgets demanded through democratic channels will not be easy, and will have deep social and political implications.

As the Financial Times admitted some time ago, opposing class interests are “putting capitalism and democracy in tension with one another”. Alongside rebellions in Parliament, therefore, the capitalist establishment will face rebellions of workers and youth on the streets.

Via borrowing, the capitalists have been kicking the can down the road. But that road is rapidly running out.

All the while, political opposition is developing on all sides. Reform UK is surging in the polls, with Farage calling out Labour for the broken state of the country’s services and infrastructure. And the Greens are picking up support on the other side.

For the ruling class, however, there is no way to restore profitability and investors’ confidence other than to carry out ruthless attacks on the working class.

Not only the Labour leaders, but British capitalism more generally, are therefore at a dead-end. And any party whose programme rests upon this bankrupt status quo will face the same fate.

If Starmer and Reeves cannot pass the policies of the capitalists, then what use are they for the bosses and bankers? The problem is, there is no other figure or party that they can safely rely on in their place.

The working class faces a similar problem: a crisis of leadership. But the Revolutionary Communist Party is working to change that.

What is needed is a militant battle against the billionaires and the rest of these parasites – to seize their wealth, wipe the debt, and expropriate the banks and monopolies.

Only by breaking with capitalism itself can we free ourselves from this endless cycle of debt, austerity, poverty, and misery.