“The modern theory of the perpetuation of debt”, wrote US founding father Thomas Jefferson, “has drenched the earth with blood, and crushed its inhabitants under burdens ever accumulating”.

The whole world is buried in debt. Deficit financing puts governments in the red by tens of billions per year. UK public debt is now over 100% of GDP. In the USA, Republicans and Democrats have been playing a dangerous game of chicken over the country’s debt ceiling, posing the threat of default in the world’s biggest economy.

And this is not even to mention low-income countries in Africa and elsewhere: trapped by immense debt burdens and spiralling repayments, and at the mercy of international finance capital.

With central banks raising interest rates in an effort to tame inflation, the question of what to do with all this debt is being posed ever-more sharply. The ruling class is even split over this question, as the recent standoff in Congress demonstrates.

But they all agree on one thing. From the bailouts of the banks, to the costs of COVID spending: the working class must be made to foot the bill.

On the left, meanwhile, there are many different ideas floating around: from the idea of a biblical-style ‘debt jubilee’, or mass cancellation; to governments printing their way out of trouble, as advocated by neo-Keynesian proponents of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

How do we make sense of this situation, where world debt stands at over 360% of global GDP? This is no mere con-trick by the capitalist class.

In truth, it is not “the modern theory of debt” that has drenched the world in blood, as Jefferson suggests, but modern capitalism, which is “dripping with blood from every pore”, to use Marx’s expression.

Under capitalism we are all, it appears, free to work wherever we choose: to buy and sell; beg and borrow. It appears purely accidental that as a product of these ‘free’ interactions, the worker is always immiserated while the capitalist is enriched.

But this is the inevitable outcome of capitalism, a system based on exploitation and profit, where the worker is never paid the full value of what they produce.

In other words, the exploitation of the majority by a tiny elite is disguised as freedom. The same is true for debt, with debtors said to be ‘voluntarily’ taking out loans. It is only ‘moral’, then, that they should repay these.

But the dominated nation, or struggling family, does not choose to be indebted, any more than the working class chooses to be exploited.

This is not a question of morals. Just as the poverty and inequality created by the capitalist system is not simply due to greed, poor policy, or free choice, neither are society’s immense debts.

The fact is that capitalism’s contradictions and crises, including the dynamite foundations of debt upon which the world economy now sits, cannot be avoided through regulation and reform. To solve the question of debt, we need a revolution.

What is money?

In some ‘left’ circles, in recent years, it has become fashionable to say that ‘money is not even real’, or to speak of a ‘deficit myth’. But the economic relations of money and debts are an objective reality under capitalism.

Marx explained that the development of money throughout history is tied with the production and exchange of commodities – goods and services produced not for subsistence, but for exchange.

In his economic writings, he showed that money functions, first and foremost, as a yardstick for the measurement of value.

Value is embedded in all commodities because they are products of labour. Commodities can be compared against one another in terms of the amount of socially necessary labour time needed to produce them. And money is the ‘universal equivalent’, against which the value of different commodities can be measured. In this way, it facilitates exchange and trade.

It is because of this unique quality – the ability to substitute itself for any other commodity in the process of exchange; to represent the exchange value of other commodities – that money can also take on other roles, acting as a unit of account, a store of value, a means of exchange, and a means of payment.

These functions are each important in their own right. Marxists, however, do not fall into the reductionist trap of the bourgeois economists, who tend to isolate one or another of these roles of money.

From this, different schools of bourgeois economics then proceed to proclaim that this or that trait is the real ‘meaning of money’, backing up their respective theories about how capitalism works.

We have seen this many times. The monetarists advocate for ‘hard cash’ and tight monetary policies, as if this could control the anarchy of capitalism. The credit theorists and Keynesians, meanwhile, see money as little more than a tool in the hands of the state, to help stimulate the economy.

The most important point emphasised by Marx is that money, and exchange value, is fundamentally a social relationship.

If you divorce money from the role that it plays in the circulation of commodities, in the social and economic interactions in society, then it necessarily gains a mystical power over us. This leads to what Marx termed ‘money fetishism’, as he explains in Capital:

“Whence arose the illusions of the monetary system? To it gold and silver, when serving as money, did not represent a social relation between producers, but were natural objects with strange social properties. And the superstition of modern economy, which looks down with such disdain on the monetary system, comes out as clear as noon-day whenever it speaks of capital!” (Our emphasis.)

Credit and crisis

The very existence of money itself throws open the door to the existence of credit, as it separates out the acts of buying and selling in regards to commodity exchange. So why not allow businesses, households, and governments to buy before they can sell?

Credit is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it helps capitalism to continue running and expanding. On the other hand, its existence also introduces contradictions and instability into the system.

Under capitalism, where a certain amount of capital is necessary for any business to expand, and commodities and money must continuously circulate, the existence of credit is not simply optional – it is essential.

In a period of capitalist upswing, the system has an insatiable appetite for credit. And even today, when the system is in crisis, credit is still required. Acting like oxygen, it allows the whole system to breathe. Similarly, you do not notice how vital it is until you are deprived of it – as in a ‘credit crunch’, when the flow of credit – good and bad – suddenly freezes.

Credit also allows the capitalists to artificially expand the market beyond its limits, by temporarily boosting consumption and demand through loans.

This is an attempt to circumvent a contradiction inherent to capitalism: the fact that workers are never paid the full value of the goods that they produce. This is the source of the capitalists’ profits – the unpaid labour of the working class. Consequently, the working class as a whole can never consume the totality of commodities that it produces.

Unless some way can be found to continue expanding the market, eventually this contradiction bursts forth in a crisis of overproduction.

Importantly, this credit is an artificial expansion. These ‘promises to pay’ are not real values. State support and stimulus, meanwhile, only push back the date of the eventual crash – all whilst piling up further contradictions.

When the crisis finally hits, as we saw in 2008, credit goes from being a source of temporary stability and growth to being a source of chaos.

Further lending dries up, as it becomes clear that goods cannot be sold, that debts cannot be repaid, and that so many claims, notes, and promises circulating around the economy are nothing but worthless pieces of paper. The slump kicks in. And panic ensues.

Senile system

Today, the debts of both individuals and states are greater than ever before. For decades, the working class has faced attacks on all fronts, including cuts to real wages and gruelling austerity. Accompanying this has been a massive expansion of credit – through mortgages, credit cards, and other means – to plug the gap in the market.

Workers are laden with student debt, medical debt, payday loans, and the like. It feels like a cruel joke: the capitalists are trying to wring even more blood from the stone, as real wages fall and rents skyrocket.

Even this is dwarfed by the levels of debt that businesses carry. Since the 2008 crash, millions of ‘zombie’ companies have been kept running only thanks to artificially low interest rates and an abundance of cheap money.

The epidemic of debt and default playing out now is a continuation of the same crisis.

Marx explained in Capital that: “The only part of the so-called national wealth that actually enters into the collective possessions of modern peoples is their national debt.”

When bubbles of private debt burst, as they did in 2008, the state is forced to step in to bail out the banks. The ridiculous proportions of state debt we see today, therefore, reflect the socialisation of private debts, which become public debts – and are thereby transferred onto the shoulders of the whole working class.

This mountain of government debt also reflects the fact that the capitalist state is continually required to save the system on behalf of the capitalist class as whole. During the pandemic, for example, trillions in state support was thrown into the global economy, massively exacerbating the problem.

Importantly, this credit can never be paid back. This is another symptom of the senility of the capitalist system, which no longer has the vigour and dynamism of yesteryear, but can only survive thanks to the iron lung of the state, paving the way for future crises.

Imperialism today

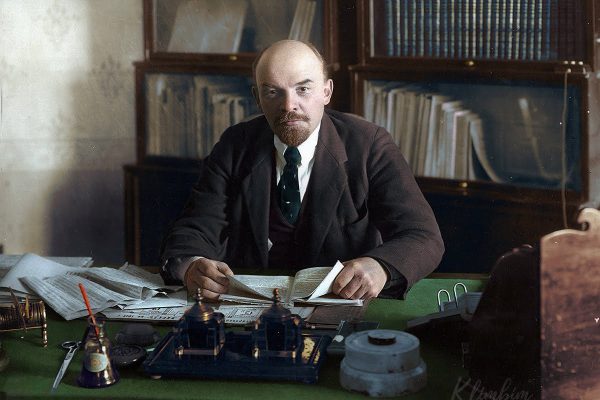

We must add to this the role played by international imperialism. As Lenin explained, finance capital has simultaneously become more and more entangled with the capitalist state, and has spread its tendrils out across the world.

Poorer countries, once directly dominated by European empires, are now indirectly dominated. Multinational companies strip ex-colonial countries of their resources and wealth, all while lending a fraction of that wealth back at tidy interest rates, in order to pay for public services, education, healthcare, infrastructure, and so on.

When a country can’t pay, the IMF comes in with a bailout package, demanding that governments open up their markets to foreign capital; attack workers and the poor; and sell off any state-owned assets. The imperialists get richer, and the masses get poorer.

How has this immense long-con been pulled off?

It is not correct to say that it is a question of force, violence, and plunder alone. “Force only protects exploitation,” explained Engels in his famous polemic Anti-Duhring, “it does not create it”.

The military power of US imperialism, for example, is made possible by the economic prosperity of US capitalism. It protects the interests of American finance capital. And the same is true of every other major imperialist power.

Now world debt is reaching a serious tipping point, causing alarm for the imperialists. Kristalina Georgieva, the managing director of the IMF, noted recently that 15% of low-income countries are already in debt distress, with almost 50% close to falling into it.

This has been exacerbated by inflation and increasing interest rates, as well as the relative strengthening of the dollar, which worsens the burden of dollar-denominated loans.

We have already seen the potential outcomes of this in Sri Lanka. Now many more countries, such as Pakistan, are already teetering on the edge of debt default or have already defaulted. Lebanon, El Salvador, Zambia – the list goes on.

The capitalist class has no answers. “The best way to escape a debt trap is to grow out of it,” says a very revealing article on the World Bank’s blog. This debt, in other words, is simply a speculative bet on the future growth of the economy.

But as the world economy slows down, stagnates, and slumps, it becomes increasingly likely that this entire house of cards will collapse into a debt crisis of epic proportions.

Debt relief and ‘forgiveness’

With living and borrowing costs rising day by day, anger is reaching new heights. In Britain and other advanced capitalist countries, boycott campaigns like ‘Don’t Pay UK’ have mushroomed. Internationally, meanwhile, we see calls for another wave of debt ‘forgiveness’ for the Global South.

In the hands of the capitalists, these measures are a joke. Take the example of the pandemic Debt Servicing Suspension Initiative. Those who participated were forced to borrow their ‘debt relief’ in dollars, and ended up worse off in the end. Zambia, for example, received $700m of debt relief. Yet their debt burden increased by $1.7bn as a result, due to the depreciation of the kwacha, the Zambian currency.

For poor countries, this scheme was a disaster. For the creditors, it was a profit bonanza.

In response to this injustice, some reformists call for much larger-scale ‘debt jubilees’, even going so far as to advocate for the total abolition of debt periodically.

Perhaps they are inspired by the Bible. According to the Book of Leviticus, at the end of every seven-year cycle, slaves would be freed and all debts would be wiped clean. One can see why this idea appeals today.

The campaign for debt jubilees internationally is best summed up by the Debt Justice Campaign. On their website, campaigners call for BlackRock CEO Larry Fink to cancel Zambia’s debt, and for the UK government to write off energy debt for households.

Such a debt relief programme, however, can only ever constitute a temporary lifting of the boot from the neck – unless it is accompanied by a mass struggle to do away with capitalism and imperialism entirely. As the Debt Justice Campaign admits:

“As part of the global Jubilee campaign, we won $130 billion of debt cancellation for lower income countries…Though this was an important victory, the structural causes that keep debt crises happening again and again, remained in place.”

The truly utopian element, however, is the idea that Larry Fink or any other capitalist could ever be persuaded to agree to ‘debt justice’; or find it in their hearts to ‘forgive’.

What underpins this is plain idealism. But the morality of class society flows from the economic needs of the system – and, above all, from the interests of the ruling class. Those who do not pay their debts, who contravene the rules of ownership, must be disciplined.

That is why countries that default on their debts find themselves economically isolated; and why individuals who refuse to pay bills or mortgages are cut off from access to energy, lose their homes, or have their credit ratings ruined. ‘Fairness’ has nothing to do with it.

Debt and revolution

For millennia, the abolition of debts and debt-slavery has been the battle cry of the impoverished masses: from the French revolution in 1789; to the plebs of ancient Rome; to the peasants in India under the British Empire.

Today, a genuinely effective campaign of debt cancellation on a mass scale could never come from the bankers and bosses, or their political representatives. It would have to come from the masses of workers and peasants across the world suffering under unending debt burdens.

Such a programme is needed now more than ever. Debt crises provide a sharp shock to society, and can often be the trigger for revolutionary movements, as was the case in Sri Lanka recently. This was seen also in Weimar Germany in 1923, where the hyperinflation crisis and subsequent revolution was triggered by a default on reparations payments.

Any move in this direction today would face fierce resistance from the ruling class. A programme of debt abolition in the current epoch would clearly be seen as a mass expropriation, and would be met with the full opposition of the bourgeois state, imperialism, and international finance capital.

So why not take it all the way? Why stop at simply cancelling the debts?

We say: These are not our debts! Expropriate the billionaire class! Make the bosses and bankers pay for this crisis!

To genuinely tackle this menace, we need a mass movement that takes aim at the conditions that have allowed such massive debts to be accumulated in the first place: the private ownership of the means of production; the division of society into an exploited and exploiting classes; and the imperialist domination over every poor and oppressed nation.

With common ownership over the means of production, under the democratic control of the working class, the economy could be planned for need, not profit.

Over time, more and more essential goods and services – such as transport, housing, energy, food, and more – would be brought out of the market, and would cease to be commodities.

Eventually, on the basis of superabundance and socialist planning, the need for money itself would wither away. And long before this, the web of debts that feed the idle rich would have been abolished.

Only on this revolutionary basis can we do away with the scourge of debt.