In the second of his four-part series about the horrific crimes committed by the capitalist class throughout history, Fred Weston discusses the monstrous fascist regimes of Hitler’s Germany and Franco’s Spain – and how the “democratic” bourgeois Establishment in Britain preferred these brutal dictatorships to the possibility of a workers’ government.

In the second of his four-part series about the horrific crimes committed by the capitalist class throughout history, Fred Weston discusses the monstrous fascist regimes of Hitler’s Germany and Franco’s Spain – and how the “democratic” bourgeois Establishment in Britain preferred these brutal dictatorships to the possibility of a workers’ government.

The rise of Hitler

For a full account and analysis of the events that unfolded in Germany in this period see Germany: from Revolution to Counter-Revolution by Rob Sewell. Here we will deal with the counter-revolutionary violence used to crush the German working class.

The most powerful and organised working class in Europe in the 1920s was the German. The German workers rose several times in an attempt to carry out revolution. In November 1918 the power was their for the taking and they could easily have moved to set up a workers’ state, but were thwarted by their own leaders. This was to have tragic consequences for the German workers in the rise of the Nazis. A few years later the Spanish workers rose in a valiant attempt to stop the spread of fascism, but were also crushed brutally.

The counter-revolutionary reaction to the 1918 German revolution was ruthless. In response to the famous Spartacist Uprising of January 1919 an offensive was launched, known as the “White Terror”. In Berlin in January, in putting down the Spartacist resistance, according to official figures, 156 workers were killed and hundreds more were wounded. In the process the two outstanding revolutionary leaders of the German working class, Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, were arrested by Freikorps officers. Liebknecht was summarily shot and Rosa Luxemburg’s head was smashed in by an officer’s rifle butt and her body was thrown into a canal.

This was just the beginning. The class struggle in Germany was not over and the working class moved repeatedly, but eventually succumbed to the Nazi counter-revolution. Smashing the power of the organised working class became the key aim of the German ruling class. As in Italy, the German bourgeoisie abandoned any pretence of bourgeois democracy and eventually handed power to the madmen of Hitler.

The consequence of all this are known to all, with the holocaust during which over eleven million people perished (some later studies indicate that the number may have been much higher). The bulk of these were Jews, around six million, but there were also disabled people, homosexuals and lesbians, gypsies and others. However, the fact that the German Communists were among the first to end up in the concentration camps is often skipped over.

In 1933 the Chief of Police of Munich issued a press statement announcing the opening of the first official concentration camp in Dachau which could hold 5,000 people. The statement made it clear that “All Communists and—where necessary—Reichsbanner and Social Democratic functionaries who endanger state security are to be concentrated here…” Most of the early victims were communists and labour movement activists!

When the Nazis occupied other countries, as they advanced, communists, socialists and anarchists were among the first to be arrested and many were summarily executed. This was the case with Spanish Republicans who had escaped to France from Franco’s bloody counter-revolution. When France was occupied by Nazi Germany in 1940, around 7,000 Spaniards who had fought bravely in the Civil War were rounded up and later died in the Nazi concentration camps.

The rise of Hitler, of course, prepared the ground for the Second World War in which over 55 million people lost their lives globally, of which around 25 million in the Soviet Union alone. This last figure highlights the fact that the Nazi regime came to power not just to destroy the German labour movement, with its trade union and political organisations, but also to strike at the Soviet Union and destroy what remained of the Russian Revolution in spite of the monstrous Stalinist degeneration, the state-owned, planned economy.

Such was the crisis of world capitalism, which expressed itself in an acute manner in Germany, that socialist revolution became a concrete possibility, as the history of that period shows. Faced with the threat of being overthrown by the German workers, in the end the ruling class was prepared to unleash the barbarism of the Nazis. The reason for this was that they needed a tool that could smash the millions strong labour movement. That was the essence of Nazism.

Today, all the “democratic” bourgeois politicians, the mainstream media, the education system, the very Establishment itself, express horror at the mere mention of what happened in Germany. And any ordinary person – except for the tiny minority of today’s fascists – is naturally horrified at what happened. But what was the position at the time Hitler came to power?

So long as Hitler did not threaten the vital interests of British imperialism, it is clear that the British ruling class saw the rise of the Nazi regime as preferable to the German working class coming to power. There was sympathy towards the Nazis – at least up to the mid-1930s – among important sections of the British establishment, even within the Royal family itself.

As Frank McDonough, in his book, The Gestapo: The Myth and Reality of Hitler’s Secret Police published in 2015, said in an interview with The Royalist: “The British ‘Establishment’, including key figures in the aristocracy, the press were keen supporters of Hitler up until the invasion of Czechoslovakia. Few were supporters of Nazism, but they admired Hitler and felt he offered the best means of preventing the spread of communism. They tended to turn a blind eye to anti-Semitism and the attacks Hitler made on communists, socialists, and other internal opponents.” [My emphasis]

Viscount Rothermere was an example of Establishment figures who admired Hitler. At that time he owned both the Mail and the Mirror. In January 1934, he had articles published in the two papers. In the Mail the headline of the article was “Hurrah for the Blackshirts”, while in the Mirror it was “Give the Blackshirts a helping hand.” Here he was backing Mosley’s attempt to replicate the Nazi party in Britain, which he later had to drop. Nonetheless, he went far further than many other establishment figures, meeting and corresponding directly with Hitler, even congratulating him when he annexed Czechoslovakia.

When Neville Henderson was made ambassador to Germany in May 1937, he wrote in The Times, “far too many people have an erroneous conception of what the National Socialist regime really stands for. Otherwise they would lay less stress on Nazi dictatorship and much more emphasis on the great social experiment which is being tried out.”

Lord Halifax as a representative of the British government visited Hitler in November 1937 and told him that people in Britain who criticised the Nazis, such as the leaders of the Labour Party, “were not fully informed’ of the “great services” that Hitler had done… “by preventing the entry of communism” into Germany, as this blocked its [communism’s] “passage further west.”

This last quote puts the position of the British capitalist class in a nutshell. It was preferable to unleash the madmen of Hitler on the German working class than to see Communism spreading westwards. Let us not forget that it was precisely the defeat of the German revolution that isolated the Soviet Union, preparing thus the material conditions for the degeneration of the workers’ state and the rise of the monster of Stalinism. Had the revolution spread to Germany, the isolation of the Soviet Union would have been broken and with the aid of the German working class, the Soviet workers could have thrown off the yolk of Stalinism and moved towards a genuine, democratic, workers’ state and the revolution would have spread throughout Europe. The fate of the Spanish revolution would have been very different.

In essence it would have meant the beginning of worldwide revolution and the downfall of capitalism globally. That is why the British elite looked with sympathy on Hitler and the Nazis in the early days of the regime. The only true anti-fascists in Britain were to be found on the left, in the trade unions, in the Independent Labour Party, Labour Party and other left forces. (This was confirmed later when many of them volunteered to go to Spain and help in the fighting against Franco.)

Those same bourgeois who looked with pleasure on the “great social experiment” of the Nazis, i.e. the butchering of hundreds of thousands, would dedicate volumes to expressing their “horror” at the violence of the Bolsheviks. Their horror was not at the violence, but at the expropriation of the capitalists and landlords!

Spanish Civil War

For a succinct analysis of the tumultuous events that unfolded in Spain in the 1930s read Ted Grant’sThe Spanish Revolution 1931-37 and for a lengthier analysis read Trotsky’sCollected Writings on The Spanish Revolution.

For a succinct analysis of the tumultuous events that unfolded in Spain in the 1930s read Ted Grant’sThe Spanish Revolution 1931-37 and for a lengthier analysis read Trotsky’sCollected Writings on The Spanish Revolution.

In the revolutions that erupted between 1917 and the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, the Spanish Revolution stands out as the last stand of the European working class in its attempt to roll back the wave of counter-revolution that had begun with the defeat of the Italian working class in 1922.

In the Spanish Revolution we saw once again the nefarious role of both the reformism of social democracy and Stalinism, which in the name of its two-stage theory and Popular Frontism contributed to the derailing of the revolution. For a few years, however, the Spanish proletariat put up a heroic fight as it desperately tried to find the road to successful revolution.

While the Spanish workers and peasants were being fed the line of the need to form an alliance with the so-called “progressive bourgeoisie”, Leon Trotsky had warned right from the beginning of the consequences of such a policy and in 1939 he commented:

“One of the most tragic chapters of modern history is now drawing to its conclusion in Spain. On Franco’s side there is neither a staunch army nor popular support. There is only the greed of proprietors ready to drown in blood three-fourths of the population if only to maintain their rule over the remaining one-fourth. However, this cannibalistic ferocity is not enough to win a victory over the heroic Spanish proletariat. Franco needed help from the opposite side of the battlefront. And he obtained this aid. His chief assistant was and still is Stalin, the gravedigger of the Bolshevik Party and the proletarian revolution. The fall of the great proletarian capital, Barcelona, comes as direct retribution for the massacre of the uprising of the Barcelona proletariat in May 1937.

“Insignificant as Franco himself is, however miserable his clique of adventurists, without honour, without conscience, and without military talents, Franco’s great superiority lies in this, that he has a clear and definite programme: to safeguard and stabilize capitalist property, the rule of the exploiters, and the domination of the church; and to restore the monarchy.

“The possessing classes of all capitalist countries – whether fascist or democratic – proved, in the nature of things, to be on Franco’s side. The Spanish bourgeoisie has gone completely over to Franco’s camp.” (Leon Trotsky, The Tragedy of Spain, January 1939)

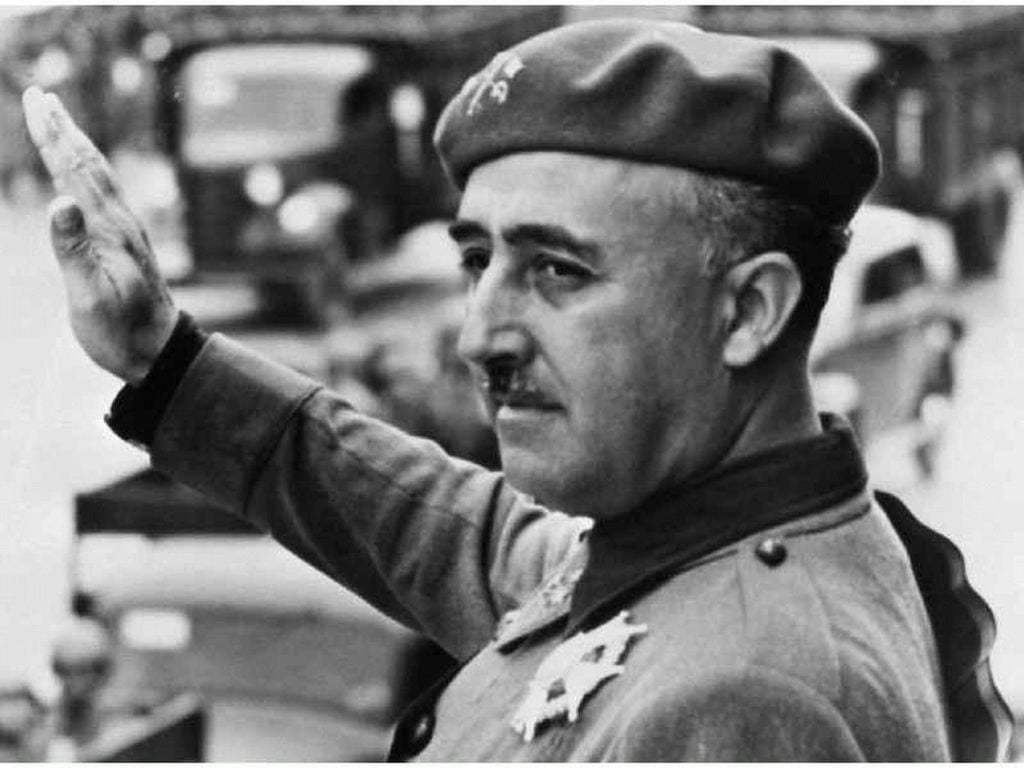

The final act of the Spanish Civil War took place at the end of March to early April 1939. On 28 March the Nationalists took Madrid and the Civil War finally came to an end on 1 April, with Franco victorious. Up to half a million people are estimated to have died. After Franco’s victory something between 250,000 and 500,000 Republican refugees fled the country and went into exile abroad. Martial law was declared and remained in effect until 1948. Hundreds of thousands of Republicans were imprisoned. And in the years 1939-43 nearly 200,000 were summarily executed or killed.

In his Time to exorcise the ghost of Franco, Jorge Martin outlines the extent of the repression:

“The exact figures are disputed, but it is calculated that between 80 and 100,000 people were killed by the fascists during the war in a campaign of systematic repression town by town, city by city, and a further 50,000 were executed by firing squads in the immediate aftermath. Up to half a million were detained in concentration camps after the end of the war in 1939. Tens of thousands of them were used as forced labour both in public works projects as well as in private companies and in the estates of landowners.

“The most glaring example is the huge fascist monument of the Valle de los Caidos (Valley of the Fallen), in El Escorial, marking those fallen in Franco’s “Glorious Crusade”, presided over by an enormous 150 metre tall cross. This was built mostly by forced labour, with many dying in the process. The monument still stands today, without the slightest modification of its meaning and symbology. Both Francisco Franco and founder of the Spanish Falange fascist party Primo de Rivera are buried here.

“Hundreds of thousands left the country as exiles and refugees during and after the war, probably up to half a million. Many of them were confined in camps in the South of France with about 12,000 being later sent to Nazi concentration camps.

“About 30,000 children were taken into custody by the Franco regime, some from Republican mothers who were jailed and others whose parents had died in the war or been executed afterwards. Many were given in adoption to Franco supporting families.”

The slaughter of the 4000 at Badajoz

An example of the brutality of Franco’s forces is provided by the Chicago Tribune in an article that appeared in the August 30, 1936 edition. The original is available here and a more easily accessible text version is available here: “Slaughter of 4,000 at Badajoz, ‘City of Horrors,’ Is Told by Tribune Man”. In introducing his article, the author writes:

“I have come from Badajoz, several miles away in Spain. I have been up on the roof to look back. There was a fire. They are burning bodies. Four thousand men and women have died at Badajoz since Gen. Francisco Franco’s rebel Foreign Legionnaires and Moors climbed over the bodies of their own dead through its many times blood drenched walls. (…) I tried to sleep. But you can’t sleep on a soiled and lumpy bed in a room at the temperature of a Turkish bath, with mosquitoes and bedbugs tormenting you, and with memories of what you have seen tormenting you, with the smell of blood in your very hair, and with a woman sobbing in the room next door.”

He explains that, “thousands of republican, socialist, and communist militiamen were butchered after the fall of Badajoz for the crime of defending their republic against the onslaught of the generals and the landowners.”

This took place in the Badajoz Bullring, and the author continues:

“They were young, mostly peasants in blue blouses, mechanics in jumpers, ‘The Reds.’ They are still being rounded up. At 4 o’clock in the morning they were out into the ring through the gate by which the initial parade of the bullfight enters. There machine guns awaited them.

“After the first night the blood was supposed to be palm deep on the far side of the ring. I don’t doubt it. Eighteen hundred men – there were women, too – were mowed down there in some 12 hours. There is more blood than you would think in 1,800 bodies.”

The numbers killed could be anything between 2000 and 4000. The exact number is not known as bodies were hurriedly taken in trucks to the local cemetery and burned, but something like 10% of the town’s population was killed!

The Málaga-Almería Massacre

What happened in Malaga in February 1937 is yet another example of the ruthless butchery carried out by the forces of Franco, this time involving some of the troops sent by Mussolini to aid in crushing the revolution, and German and Italian warplanes. There are many accounts of this event, but I will provide one here, which I quote fully, “The Crime on the Road Malaga-Almeira”, written by a Canadian doctor, Norman Bethune, who, with a team of medical staff, came to the aid of the fleeing refugees in an ambulance. Excuse the length of the quote, but it would not do justice to the text to take only one fragment.

This is what doctor Bethune wrote in 1937:

“The evacuation en masse of the civilian population of Malaga started on Sunday Feb. 7. Twenty-five thousand German, Italian and Moorish troops entered the town on Monday morning the eighth. Tanks, submarines, warships, airplanes combined to smash the defenses of the city held by a small heroic band of Spanish troops without tanks, airplanes or support. The so-called Nationalists entered, as they have entered every captured village and city in Spain, what was practically a deserted town.

“Now imagine one hundred and fifty thousand men women and children setting out for safety to the town situated over a hundred miles away. There is only one road they can take. There is no other way of escape. This road, bordered on one side by the high Sierra Nevada mountains and on the other by the sea, is cut into the side of the cliffs and climbs up and down from sea-level to over 500 feet. The city they must reach is Almeria, and it is over two hundred kilometers away. A strong, healthy young man can walk on foot forty or fifty kilometers a day. The journey these women children and old people must face will take five days and five nights at least. There will be no food to be found in the villages, no trains, no buses to transport them. They must walk and as they walked they staggered and stumbled with cut, bruised feet along that flint, white road the fascists bombed them from the air and fired at them from their ships at sea.

“Now, what I want to tell you is what I saw myself of this forced march — the largest, most terrible evacuation of a city in modern times. We had arrived in Almeria at five o’clock on Wednesday the tenth with a refrigeration truckload of preserved blood from Barcelona. Our intention was to proceed to Malaga to give blood transfusions to wounded. In Almeria we heard for the first time that the town had fallen and were warned to go no farther as no one knew where the frontline now was but everyone was sure that the town of Motril had also fallen. We thought it important to proceed and discover how the evacuation of the wounded was proceeding. We set out at six o’clock in the evening along the Malaga road and a few miles on we met the head of the piteous procession. Here were the strong with all their goods on donkeys, mules and horses. We passed them, and the farther we went the more pitiful the sights became. Thousands of children, we counted five thousand under ten years of age, and at least one thousand of them barefoot and many of them clad only in a single garment. They were slung over their mother’s shoulders or clung to her hands. Here a father staggered along with two children of one and two years of age on his back in addition to carrying pots and pans or some treasured possession. The incessant stream of people became so dense we could barely force the car through them. At eighty eight kilometers from Almeria they beseeched us to go no farther, that the fascists were just behind. By this time we had passed so many distressed women and children that we thought it best to turn back and start transporting the worst cases to safety. It was difficult to choose which to take. Our car was besieged by a mob of frantic mothers and fathers who with tired outstretched arms held up to us their children, their eyes and faces swollen and congested by four days of sun and dust.

“’Take this one.’ ‘See this child.’ ‘This one is wounded.’ Children with bloodstained rags wrapped around their arms and legs, children without shoes, their feet swollen to twice their size crying helplessly from pain, hunger and fatigue. Two hundred kilometers of misery. Imagine four days and four nights, hiding by day in the hills as the fascist barbarians pursued them by plane, walking by night packed in a solid stream men, women, children, mules, donkeys, goats, crying out the names of their separated relatives, lost in the mob. How could we chose between taking a child dying of dysentery or a mother silently watching us with great sunken eyes carrying against her open breast her child born on the road two days ago. She had stopped walking for ten hours only. Here was a woman of sixty unable to stagger another step, her gigantic swollen legs with their open varicose ulcers bleeding into her cut linen sandals. Many old people simply gave up the struggle, lay down by the side of the road and waited for death.

“We first decided to take only children and mothers. Then the separation between father and child, husband and wife became too cruel to bear. We finished by transporting families with the largest number of young children and the solitary children of which there were hundreds without parents. We carried thirty to forty people a trip for the next three days and nights back to Almeria to the hospital of the Socorro Rojo Internacional where they received medical attention, food and clothing. The tireless devotion of Hazen Sise and Thomas Worsley, drivers of the truck, saved many lives. In turn they drove back and forth day and night sleeping out on the open road between shifts with no food except dry bread and oranges.

“And now comes the final barbarism. Not content with bombing and shelling this procession of unarmed peasants on this long road, but on the evening of the 12th when the little seaport of Almeria was completely filled with refugees, its population swollen to double its size, when forty thousand exhausted people had reached a haven of what they thought was safety, we were heavily bombed by German and Italian fascist airplanes. The siren alarm sounded thirty seconds before the first bomb fell. These planes made no effort to hit the government battleship in the harbor or bomb the barracks. They deliberately dropped ten great bombs in the very center of the town where on the main street were sleeping huddled together on the pavement so closely that a car could pass only with difficulty, the exhausted refugees. After the planes had passed I picked up in my arms three dead children from the pavement in front of the Provincial Committee for the Evacuation of Refugees where they had been standing in a great queue waiting for a cupful of preserved milk and a handful of dry bread, the only food some of them had for days. The street was a shambles of the dead and dying, lit only by the orange glare of burning buildings. In the darkness the moans of the wounded children, shrieks of agonized mothers, the curses of the men rose in a massed cry higher and higher to a pitch of intolerable intensity. One’s body felt as heavy as the dead themselves, but empty and hollow, and in one’s brain burned a bright flame of hate. That night were murdered fifty civilians and an additional fifty were wounded. There were two soldiers killed.

“Now, what was the crime that these unarmed civilians had committed to be murdered in this bloody manner? Their only crime was that they had voted to elect a government of the people, committed to the most moderate alleviation of the crushing burden of centuries of the greed of capitalism. The question has been raised: why did they not stay in Malaga and await the entrance of the fascists? They knew what would happen to them. They knew what would happen to their men and women as had happened so many times before in other captured towns. Every male between the age of 15 and 60 who could not prove that he had not by force been made to assist the government would immediately be shot. And it is this knowledge that has concentrated two-thirds of the entire population of Spain in one half the country and that still, held by the republic.” (The crime on the road Malaga-Almeria)

[For anyone who wants to read further on this event, eyewitness accounts of the same events are available in Spanish at La voz de la desbandá: los supervivientes de la Carretera Málaga-Almería. Another account, with photos and videos, in Spanish, is available at 80 aniversario: La carretera Málaga-Almería, la masacre silenciada de la Guerra Civil. In English, Dialogue with Death – The Journal of a Prisoner of the Fascists in the Spanish Civil War available from The University of Chicago Press, also gives an insight into the situation in malaga after it was taken by Franco’s’ troops.]

According to Professors at the University of Malaga “over 5,000 people died on the road, based on oral histories collected, plus burial records in Salamanca, and Málaga archives.”

Catholic Church on the side of the butchers

In the face of such mass scale butchery, what was the position of the Catholic Church? To begin with, as early as August 1938 the Vatican officially recognised the Franco’s regime, even before the Republic had been totally crushed. Throughout the Civil War the Catholic hierarchy had de facto backed Franco.

For example, the Bishop of Pamplona declared the war a “religious crusade” on 15 August 1936, identifying Franco’s forces as “crusaders”. The following month, in September 1936, the Archbishop Enrique Pla y Deniel, declared the war to be a crusade “for the defence of Christian civilisation”. A couple of months later, Cardinal Isidro Gomá, again declared the war to be a religious crusade in defence of Catholicism.

“Even before the war ended the repressive nature of Franco’s regime was becoming apparent; and yet the bishops, through their silence, legitimized the brutal retaliations carried out against the enemies of the Crusade. There was no protest at the mass executions of supporters of the Republic, or of the degrading treatment meted out to their female relatives.

“Cardinal Gomá, in a report to the Vatican Secretary of State as early as August 1936, acknowledged that perhaps some reproach should be made to the Falange for the severity of the reprisals, but no such reproach was ever made. (…)

“On 29 May 1939, Franco presented his sword to Cardinal Gomá in the Church of Santa Bárbara, Madrid; a symbolic representation of the victory shared by State and Church.” [My emphasis] [Source]

The “Non-Intervention Committee”

It is significant that while Mussolini and Hitler helped Franco by sending soldiers and weapons, the support of the “bourgeois democracies” for the Republic was far less concrete. They in fact promoted a so-called “Non-Intervention Committee”, signed by 27 countries including Britain, France, the Soviet Union, Germany, and Italy, whose sole purpose was to stop aid reaching the Republic – while the Nazis and Fascists ignored the agreement and went ahead with military intervention.

It is significant that while Mussolini and Hitler helped Franco by sending soldiers and weapons, the support of the “bourgeois democracies” for the Republic was far less concrete. They in fact promoted a so-called “Non-Intervention Committee”, signed by 27 countries including Britain, France, the Soviet Union, Germany, and Italy, whose sole purpose was to stop aid reaching the Republic – while the Nazis and Fascists ignored the agreement and went ahead with military intervention.

Mussolini, during the first three months of the Non-Intervention Agreement sent 90 Italian aircraft to help Franco. To this was added 2,500 tons of bombs, 500 cannons, 700 mortars, 12,000 machine-guns, 50 whippet tanks and 3,800 motor vehicles, and around 50,000 regular troops and 30,000 fascist militiamen.

Hitler provided the infamous Condor Legion, placed under the direct command of Franco himself, with up to 12,000 men, backed by bomber planes that were used during the Civil War. The famous painting by Pablo Picasso, “Guernica”, in response to the bombing by German and Italian warplanes of Guernica, a village in the Basque Country, is a reminder of what really happened.

Writing on the outbreak of civil war in Spain in the Evening Standard on 10 August 1936, Churchill stated the following: “It is of the utmost consequence that France and Britain should act together in observing the strictest neutrality themselves and endeavouring to induce it in others. Even if Russian money is thrown in on the one side, or Italian and German encouragement is given to the other, the safety of France and England requires absolute neutrality and non-intervention by them.”

The League of Nations – the precursor to today’s United Nations and equally impotent – condemned the intervention of Germany and Italy, but continued to put forward non-intervention and “mediation”. The reason for this is clear: all the main bourgeois powers saw in the possible victory of the Republic the rise of the revolutionary working class of Spain. Objectively speaking, they all had an interest in the crushing of the Spanish Revolution.

In the face of the butchery carried out by Franco, the “democracies”, i.e. the ruling classes of Europe, together with the Church, did not lift a finger, for to do so would mean facilitating the task of the Spanish working class, which was the overthrow of capitalism. Thus, for the ladies and gentlemen sitting in comfort and luxury in Paris, London and other capitals of Europe, the regime of terror unleashed by Franco was preferable to any government under which the workers could have taken power, for had this happened, the wave of revolution that had been blocked by the rise of Hitler in 1933, could once again have swept across Europe.

With the Spanish Revolution clearly defeated, on 27th February 1939, the British government had no problem in recognising Franco as the new ruler of Spain. The defeat of the Spanish Revolution, however, was not a defeat for the Spanish workers alone. It was a defeat for the workers of the world, as once the last bastion of workers’ struggles had been snuffed out, the national ruling classes of Europe could turn to more pressing business, a war to decide who dominated the world markets, the Second World War.

The Second World War ended with the collapse of the Nazi regime, but Franco did not forget the friends that had helped in his hour of need. Under Franco, Spain was to provide asylum for thousands of Nazis fleeing arrest and trial.

Compare this behaviour to what the capitalist powers did after the Russian Revolution. There was no “Non-Intervention Committee” then! On the contrary, armies attacked the Soviet Union from all directions. Here we see the priorities of the capitalist class. In the Soviet Union they intervened because their vital material interests were at risk, whereas in Spain their vital interests were better served by not intervening and allowing Franco to come to power, even if this meant hundreds of thousands butchered.