Resisting pressure from the leaders of various Commonwealth countries, first Starmer and then King Charles have doubled down on Britain’s role in the transatlantic slave trade.

They have categorically refused to offer any reparations for the exploitation of its former colonies – of which some estimates value as high as 18 trillion pounds. They have even refused to offer a symbolic apology to any of the countries involved.

Instead, Starmer has offered the usual platitudes about “looking forward, not backwards”, and pleas for us to stop living “in the shadow of the past”.

The furthest he has been willing to budge on the issue is considering “non-cash” options… like ‘helping’ ex-colonial countries fight climate change!

‘Sir’ Keir is simply following the long and rich tradition of British politicians who gloss over British imperialism’s bloody history, and who repeat the common myth that ‘British moral superiority’ is what ended the slave trade.

Saying the quiet part out loud, former Tory MP Jacob Rees-Mogg said that former colonies “should pay us” for ending slavery, attributing the abolition of slavery to “Christian charity”.

They ought to pay us for ending slavery, it is not something any other country had done and we were motivated by Christian charity. https://t.co/cdJzJq0r7C

— Jacob Rees-Mogg (@Jacob_Rees_Mogg) October 15, 2024

As the following article (see below) will explain, this is total fiction, crafted to obscure the bloody history of the capitalist system that Starmer, King Charles, Rees-Mogg, and the rest of them protect.

This article is a part of a brand new booklet, The Crimes of British Imperialism, which uncovers the bloodstained history of the world’s oldest capitalist power.

The booklet has been produced as part of the Revolutionary Communist Party’s ‘Books not Bombs’ campaign. The first step towards fighting imperialism and militarism – in Britain and across the globe – is to understand it from a scientific, Marxist perspective.

Our aim with this collection of articles is to educate communists in how to fight imperialism today.

We aren’t interested in empty apologies from imperialism’s present-day defenders – least of all those like David Lammy, who cynically use the language of anti-colonialism to cloak their western imperialist agenda.

We – the working class – can only bring justice to the innumerable victims of imperialism by fighting to uproot the entire system that caused these crimes in the first place.

Pre-order The Crimes of British Imperialism today.

[Note: For the sake of clarity, ‘Britain’ is used throughout the article, even for times before the 1707 Act of Union]

Anybody that has gone through the British education system will have been taught about Britain’s role in the transatlantic slave trade, the brutal kidnapping of tens of millions of West Africans to work in squalid conditions as slaves in the West Indies.

You will likely have been taught that the British weren’t as ruthless as the French, or not quite as prolific as the Portuguese. And of course, who can forget that it was the British who came to their senses and abolished the entire institution before any other power had even thought of it, all thanks to the moral superiority of the British character.

For example, a 2024 article from The Spectator writes:

“The largely successful British effort to eradicate the transatlantic slave trade did not grow out of any kind of self-interest. It was driven by moral imperative and at considerable cost to Britain and the Empire.”

This is complete fiction.

Britain was one of the key architects and the dominant power in the slave trade throughout the 18th Century and the beginning of the 19th. It was on the backs of millions of slaves that British capitalism came to dominate the globe, lay the foundations for world trade, and that its empire was able to rule the waves.

Triangular trade

Britain had a presence in the West Indies since the mid 16th Century, mainly as outposts for raiding Spanish ships. This was followed by permanent settlements in the early 17th Century, consisting of Puritans looking to escape the repression of the Stuart monarchy, as well as small numbers of slaves to work the land.

In the middle of the century the monarchy was smashed in the English Revolution, and the bourgeois had seized power. After Cromwell’s brutal subjugation of Ireland, the British deported over 50,000 Irish prisoners to the Caribbean, who worked as indentured servants and as slaves.

They were sent across the Atlantic to Britain’s newly conquered Caribbean territories. They had seized Jamaica in 1655 and this was swiftly followed by a number of other islands in the Caribbean.

New territories, as well as growing demand for raw materials from British industry, created new demand for slaves to work the plantations. Rather than continually warring with the Irish, they instead looked to the West Coast of Africa for slaves – an area they had already been using to mine gold.

It was this that led to the development of ‘triangular trade’, the main process by which the transatlantic slave trade took place.

British ships sailed to West Africa and set up fortresses on the coast, trading manufactured goods with local elites, merchants, and rulers who brought captive locals to sell into slavery. This often wasn’t sufficient to meet the demand for slaves that the plantations needed, and so:

“[When they] found that peaceful commercial relations alone did not generate enough enslaved Africans to fill the growing demands of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, they formed military alliances with certain African groups against their enemies. This encouraged more extensive warfare to produce captives for trading.”

Initially, this was all carried out by the Royal African Company, in which infamous Bristol slaver Edward Colston was a major shareholder. This was established in 1660 as a royal monopoly to oversee this increasingly lucrative venture. At this stage, around 5,000 slaves a year were transported to work in the colonies.

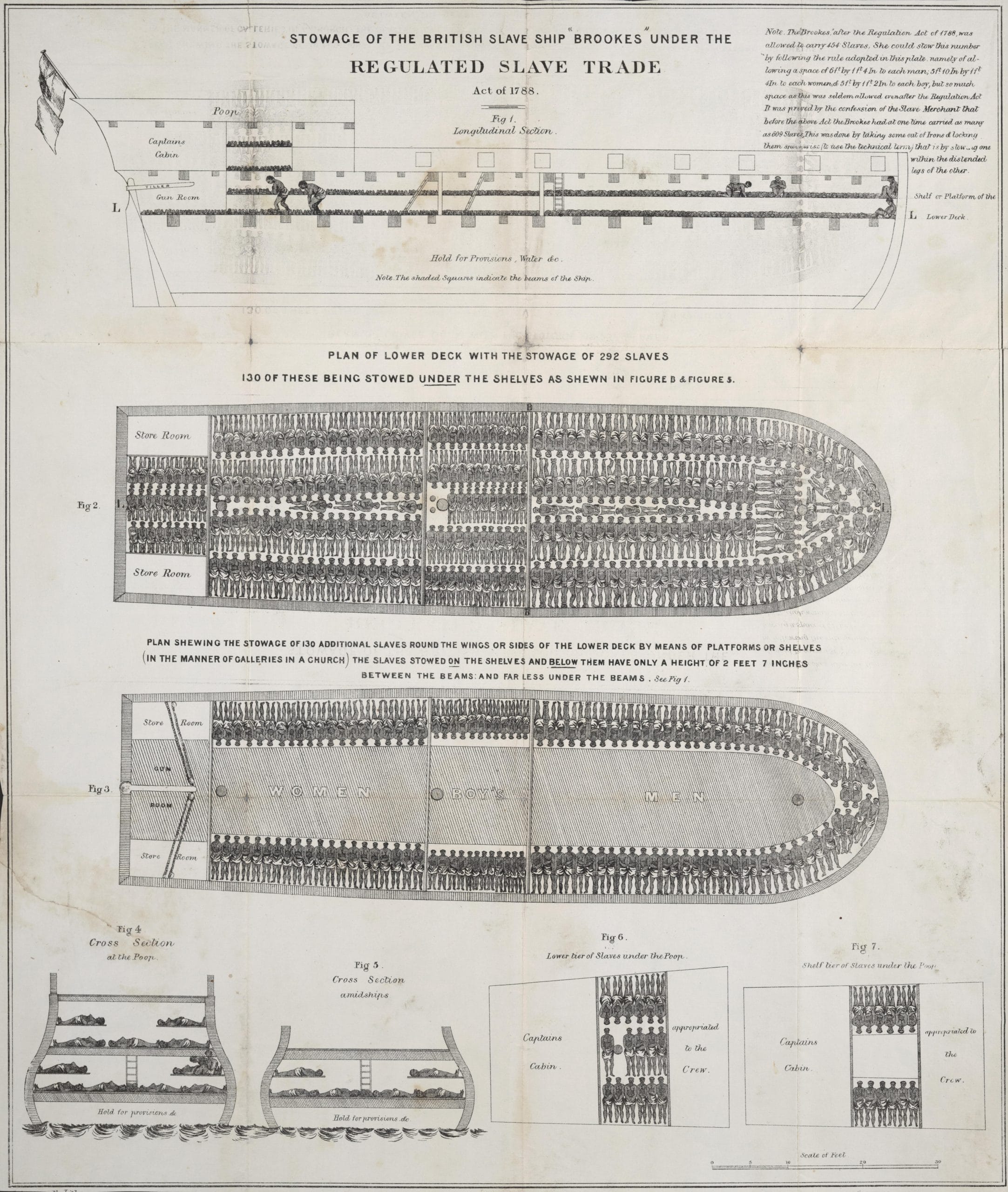

Once purchased, they were loaded into ships and sailed across the Atlantic to the West Indies. During the ‘middle passage’, Africans were chained together and trapped in the hold, often way over capacity. Over 2,000,000 died of disease, malnutrition, or were murdered by the crew before they even made it to the Caribbean.

In 1781, the Zong – a British slave ship – embarked on the middle passage with over 400 slaves on board, over twice the capacity. Faced with dwindling water supplies, the slavers threw over 100 captives overboard, half of whom were women and children.

In defiance of this, many committed suicide, whilst others begged to be starved rather than face the sharks that followed the ships. This was typical of a slave ship in this period.

Surviving the journey meant being sold to plantations where the slaves were subject to backbreaking labour growing crops such as cotton, tobacco, coffee, and cacao. Whilst working they were whipped and beaten, to ensure obedience.

It was common for the British in this period to describe the slaves as “two legged cattle”. They were seen as commodities or natural resources made to be exploited, not as human beings. The life expectancy of a slave was under a decade.

As Marx explained in Capital:

“It is accordingly a maxim of slave management, in slave-importing countries, that the most effective economy is that which takes out of the human chattel in the shortest space of time the utmost amount of exertion it is capable of putting forth. It is in tropical culture, where annual profits often equal the whole capital of plantations, that negro life is most recklessly sacrificed. It is the agriculture of the West Indies, which has been for centuries prolific of fabulous wealth, that has engulfed millions of the African race. It is in Cuba, at this day, whose revenues are reckoned by millions, and whose planters are princes, that we see in the servile class, the coarsest fare, the most exhausting and unremitting toil, and even the absolute destruction of a portion of its numbers every year.”

The masses of raw materials produced were then shipped back to Britain and used to meet the growing demands of industry. Protectionist measures tied the whole process together, protecting nascent British industry. The Navigation Acts gave British ships sole rights to handle British goods, and sugar sources outside of the British West Indies were burdened with tariffs.

Conquest

The first controversy surrounding Britain’s involvement in the slave trade related to the Royal African Company itself. It had nothing to do with any moral scruples about slavery however, but that its status as a royal monopoly prevented other merchants from getting involved.

Parliament, representing the interests of the bourgeoisie, fought for the RAC to be abolished and for free trade, to sweep away this last vestige of feudal particularism and let them get rich from the slave trade.

The first struggle relating to slavery therefore was not to abolish it but to expand it! They won in 1697.

Having removed this obstacle, the scope of the slave trade ballooned, and Britain was at the very heart of it. Bristol alone shipped 161,000 slaves in the first nine years.

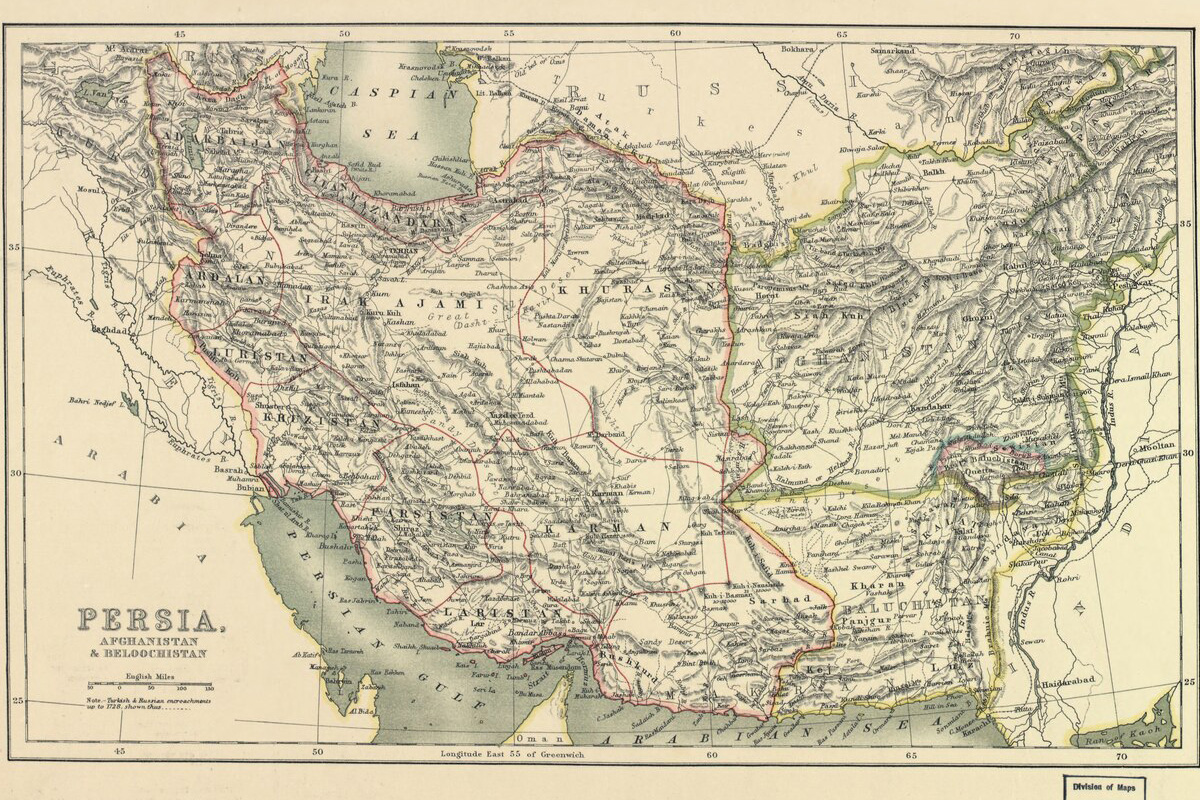

Wars with rival powers such as Spain allowed Britain to increase its dominance and become the number one power in the Atlantic. After concluding war with Spain in 1713, Britain seized Gibraltar, Minorca, and the Asiento de Negros, which gave them 30 years of monopoly rights to selling slaves to the Spanish colonies.

This right was granted to the South Sea Company, the shareholders of which included 460 Members of Parliament, 100 Lords, and the entire royal family. The tradition of the British bourgeoisie so far is therefore one of fighting tooth and nail for their ‘God given’ right to put man into bondage and work him to death for their own profit.

By the end of the 17th Century, the transatlantic slave trade was in full swing, and Britain was its chief architect. This, however, was only the beginning. So far, only 16% of slaves that would be transported over the course of the trade had been. The bulk occurred in the 18th Century, where Britain rose to the position of the dominant slave power of the world, overtaking the Portuguese and maintaining its spot for over 80 years.

Britain’s brutal role

In all, the conservative estimate is that a total of 12,500,000 Africans were enslaved and sailed across the Atlantic. Of this figure, Britain and Portugal together took 9,000,000 of them, 3,500,000 of which were taken by the British.

Not included in this figure are the 4,000,000 Africans who died between being captured and marched to the ports on the West Coast of Africa. Forced marching, disease, brutal slave raids, and conflicts manufactured by slavers were responsible for upward estimates of 40,000,000 deaths before they had even made it to the ships.

To justify their brutalities, all sorts of racist ideas were concocted and codified into law. The Barbados slave code, the first of its kind, was used as a model across Britain’s colonies. It stated:

“If any Negro or slave whatsoever shall offer any violence to any Christian by striking or any other form of violence, such Negro or slave shall for his or her first offence be severely whipped by the Constable.

For his second offence of that nature he shall be severely whipped, his nose slit, and be burned in some part of his face with a hot iron. […] And being brutish slaves, [they] deserve not, for the baseness of their condition, to be tried by the legal trial of twelve men of their peers, as the subjects of England are.

And it is further enacted and ordained that if any Negro or other slave under punishment by his master unfortunately shall suffer in life or member, which seldom happens, no person whatsoever shall be liable to any fine therefore.”

A highly profitable venture

Cheap raw materials to feed the fires of industry, alongside new markets to sell its commodities to, created a huge amount of profit. This was ploughed into industry, leading to a rapid development of British capitalism.

Bristol, already an important city, became the centre of the entire slave trade, accounting for about 40% of Britain’s slave voyages at one point.

It would later be supplanted by Liverpool, which was a fairly insignificant port until its easy access to the Atlantic made it a new hub, bringing in tens of millions of pounds every year.

Manchester, through its proximity to Liverpool, was also raised from nothing into the beating heart of the cotton industry. From 1785-1830 its population increased seven times, and the value of cotton-manufactures exported from Britain increased from £1,000,000 to £31,000,000.

In the same period, the quantity of cotton that Britain imported to feed its factories increased from 11,000,000lb a year to 283,000,000lb a year.

Workshop of the world

This was a part of British capitalism’s period of primitive accumulation, where through the most violent acts imaginable it brought together the conditions necessary for ‘free’ capitalist development.

Britain’s status as the workshop of the world was made possible by the immense levels of profit generated by the slave trade. It was the blood, sweat, and tears of millions of slaves that would provide a large amount of the resources needed for the industrial revolution.

The steam engine, the symbol of British power, was initially partially financed by the William Deacon Bank, which emerged directly out of the need to finance increasingly costly voyages across the Atlantic.

As the scale of production increased, as well as the cost of increasingly large slave voyages, so did the amount of investment needed. Many British banks – or their component parts before mergers – originated in this period, rising out of the growing demands of commodity production.

The most notable example is Barclays. Much of the Barclay family made their millions through slavery. The William Deacon Bank today is incorporated in the RBS/Natwest group.

At this stage there was very little abolitionist sentiment, other than amongst certain radicals on the fringes. Simply put, slavery was far too profitable for anybody to even consider abolishing it.

Reaching its limits

It was only towards the end of the 18th Century that the cause for abolitionism began to strengthen. Whilst there were many honest fighters for this cause, the movement grew in strength because the colonies in the West Indies were becoming less profitable.

Stripped of nutrients from a century of intensive farming, the British West Indies were struggling to compete with the vast and fertile soil of Cuba, Brazil, and the French colony of Saint Domingue, now Haiti.

So desperate were the British ruling class to get their hands on Saint Domingue they attempted to invade it during the Haitian Revolution of 1791, an adventure that failed spectacularly.

Britain’s colonial possessions in the East Indies (i.e. the Indian subcontinent) were also rising in importance. Between 1791-1833, sugar imports from the British East Indies increased twenty three times. In the West Indies sugar was king, 72% of Barbados and the Leeward Islands was occupied with sugar.

Unable to compete with the cheap sugar produced in India, the West Indies had to rely on their protectionist privileges to stay competitive, as the East Indies imports were burdened with tariffs.

There was also the American Revolution in 1775, the ending of which in 1783 kicked the British out and weakened their dominance in the Caribbean sea.

The battleground had been prepared for a struggle between the landed interests of the West Indies planters – who wished to maintain protectionism to stay alive – and the advocates of free trade – who saw the West Indies plantations as an archaic hindrance to further growth.

Economists such as Adam Smith and David Ricardo became the voices for this movement; they carried out a full on ideological assault against monopolies and protectionism.

Economics of slavery

All of these different events expressed the same undeniable truth: that slavery was running into its limits, and was unable to keep up with the galloping pace of British industrial development.

Slaves on the plantations were using the same tools in 1831 as they were in 1631. There is very little scope or incentive to invest in new technologies and technique, as slaves have very little incentive to increase their productivity.

Tools would often be sabotaged and destroyed in protest against their enslavement, and regardless of how much sugar cane they pick in a day, a slave remains a slave at the end of it.

Birth rates amongst slaves were very low, and infant mortality was over 50%, so a constant source of new slaves from West Africa was required to keep the plantations functional. This got increasingly expensive the longer it went on, as the price of slaves increased.

The combination of West Indies sugar being more expensive than sugar produced elsewhere, Napoleon’s blockade of Britain’s access to European markets, and the saturation of markets back in Britain caused the plantations to enter into a period of crisis. Around 65 plantations in Jamaica alone were abandoned in this period, and the slaves killed.

Slave rebellions

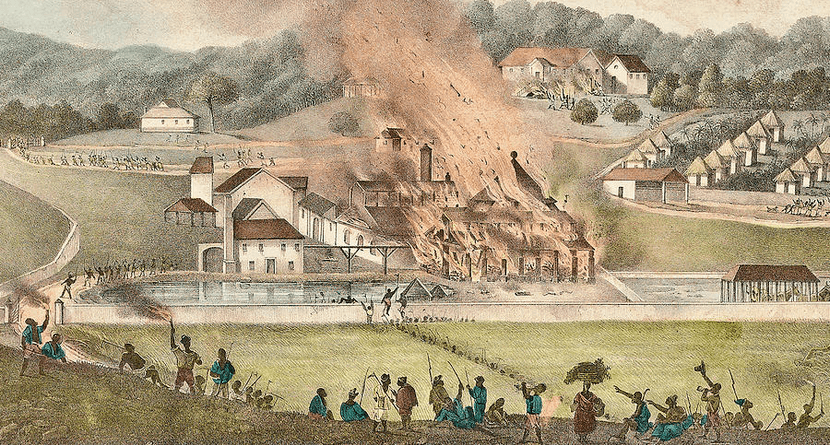

The intolerable, inhuman conditions naturally led to a string of slave rebellions. These were heroic uprisings of slaves who could not bear another moment of being chattel. The stakes were clear from the beginning: success and freedom or failure and death.

In Jamaica, the colony that “no Country excels in a barbarous treatment of slaves, or in the cruel methods they put them to death”, hundreds of slaves rose up in 1760 in ‘Tacky’s Revolt’.

Despite no military training, they managed to fight back the British for a year through intense guerilla warfare before being defeated and brutalised in 1761.

In 1816, Barbados saw its largest slave rebellion, led by Bussa. Over 5,000 slaves rose up, with 500 or so organised into a militia. The British greeted the crudely armed militias with cannons, and executed over half the rebels after defeating the uprising.

This was closely followed by the Demerara rebellion in 1823, the largely peaceful nature of which did not prevent the British from killing 500 men, women, and children and slinging up the bodies of the leaders in public for all to see.

Finally there is the Baptists War, also known as the Great Slave Rebellion in Jamaica. 60,000 slaves (out of 300,000 total on the island) rose up and called for a general strike on the island.

Before being crushed by British forces, they managed to inflict multiple defeats on local militias, and many escaped into the countryside before being killed.

Whilst none of these heroic rebellions succeeded in their final goals, they did drive up the cost of maintaining the slave system for the British ruling class.

Abolition

By the turn of the 19th Century, the capitalists of Britain were singing the song of abolition. In 1807, parliament passed the Slave Trade Act, which banned the slave trade but didn’t emancipate those already enslaved. This was partly a compromise between the industrialists in Britain and the West Indian landed interests, who still had a strong presence in parliament.

Not for one moment was there a whiff of moral sentiment in banning the trade. Simply put, abolitionism gained traction when slavery ceased to be profitable.

The twenty five years between the banning of the trade and full emancipation was one of palliative care for the West Indies plantations. Some sources say that by 1828 the West Indies amounted to a yearly loss of £1,500,000 for the British economy.

In the past the West Indies sugar monopoly, alongside other protectionist measures, played an important role in protecting British industry, which was still young and developing. These had now served their purpose, and had become a hindrance on further development.

For example, far from damaging profits, the independence won by the USA in the late 18th Century actually increased profits for Britain, as they made far more from the US as a partner in trade than they did as a slave colony.

In 1833 parliament passed An Act for the Abolition of Slavery which abolished slavery across the British empire. Everywhere other than Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Saint Helena, and territories administered by the East India Company. In other words, the places where slavery was still turning a profit.

£20,000,000 in compensation was paid out to the slave owners for their trouble. To pay for this, a loan was taken out that equated to 40% of GDP which was only paid off in 2015.

Freed slaves were then subject to a six year ‘apprenticeship’ where they worked for free for their former masters in order to learn “how to live as free men”. ‘Freed’ slaves would be forgiven for not noticing the difference between the apprenticeship and their former bondage.

Britain’s fight for freedom

Britain’s involvement with slavery and the slave trade did not cease after abolishing it in 1833.

Manchester and Liverpool provided cotton-manufactures and shackles to slave hunters on the West African Coast, as well as to plantations in Cuba and Brazil. Hundreds of thousands of guns manufactured in Birmingham were exported to slave colonies to help round them up and put down their rebellions.

Around 70% of the shackles, chains, and other tools that Brazil used for their own slave plantations were produced in Britain.

And of course there is sugar, which was a major British export across the world. The attitude of the British ruling class was that “gold doesn’t stink”, as summarised in this speech given to the Commons by the pro-slavery Lord Macaulay:

“We import the accursed thing; we bond it; we employ our skill and machinery to render it more alluring to the eye and to the palate; we export it to the Leghorn and Hamburg; we send it to all the coffee houses of Italy and Germany; we pocket a profit on all this; and then we put on a Pharisaical air; and thank God that we are not like those sinful Italians and Germans who have no scruple about swallowing slave-grown sugar.”

On the pretext of enforcing abolition, the Royal Navy was mobilised to patrol the West African coast. This had a marginal impact (if any) on stopping slave ships, but it was used as a means of establishing the full British colonies of The Gambia, Sierra Leone, Gold Coast, and Nigeria.

The same justification was used to justify Britain’s Eastward expansion across the continent, and was one of the arguments used by the other major powers to justify the scramble for Africa. Here Britain would commit some of its greatest atrocities.

The final nail in the coffin of the British ruling class’ story about their moral crusade is the American Civil War of 1861-65.

Britain came very close to officially recognising the Confederacy and entering the war on the side of the slave-owning South. The vast majority of the cotton that fuelled British factories was bought from the slave plantations in the South and so they weren’t keen on pushing for abolition when it hurt their wallets.

Lessons on slavery often focus on the horrors of chattel slavery in the South of the US however, these plantation owners learnt all they knew about slavery from their old British masters.

A major reason why Britain didn’t enter the war was that there was mass opposition to it in the ranks of the working class. Despite unemployment caused by the drying up of cotton imports, British workers stood in full solidarity with the North, and refused to handle Southern cotton.

Abraham Lincoln personally thanked the international solidarity of the workers of Manchester in a letter, saying that “I cannot but regard your decisive utterances on the question as an instance of sublime Christian heroism which has not been surpassed in any age or in any country.”

Rotten traditions

The abolition of the slave trade in 1807 is often taught to be the end of any atrocities that the British Empire committeed.

Again, this is total fiction.

Abolition marked a turning point for the British Empire, it was in this period that Britain grew to dominate not just the Atlantic but the entire world. Far from being done with brutality and slaughter, the bloody history of British capitalism was just getting into full swing.

As Marx said in Capital:

“The discovery of gold and silver in America, the extirpation, enslavement and entombment in mines of the aboriginal population, the beginning of the conquest and looting of the East Indies, the turning of Africa into a warren for the commercial hunting of black-skins, signalised the rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production. These idyllic proceedings are the chief momenta of primitive accumulation.

The veiled slavery of the wage workers in Europe needed, for its pedestal, slavery pure and simple in the new world.”