The chaotic process of Brexit reflects the long-term decline and decay of British capitalism. But this turbulence, in turn, is not confined to the UK. The whole of European capitalism is equally crisis-ridden. As Josh Holroyd discusses, the future for both the UK and EU under capitalism is one of stagnation, slump, and austerity.

In the language of the markets, a “correction” is when overvalued stocks suffer a sudden drop in price, reflecting their real value. In effect, Brexit represents a very similar process but on a much greater scale: that of British capitalism as a whole.

Over the best part of a century, the UK has been in an interminable state of decline economically, diplomatically and militarily. The key to this is a long-term crisis in productivity caused by a chronic lack in investment. A 2015 report from the Office of National Statistics showed the extent of the rot: a worker in France now produces more in four days than a British workers would in five, despite working shorter hours.

Such a huge competitive disadvantage was bound to make itself felt, first in the wave of deindustrialisation which swept the country from the 1970s onwards, and eventually in the growing insignificance of British power on a world stage. For a period, the UK was able to maintain a certain status through its so-called “special relationship” with the USA, its parasitical position as a centre for world finance, and crucially, its membership of the European Single Market. Brexit has now called all of these into question.

The collapse of sterling since the vote last year (in June it was still at 13.7% below its pre-referendum value) is an eloquent appraisal of the real strength of the British economy, and as Brexit negotiations continue, the UK will finally be forced to accept a position which in reality it has occupied for a long time.

This fact is keenly felt by the British Establishment, including its representatives in the Labour movement, the Blairites. Chuka Umunna recently attempted to commit the government to retaining Single Market membership during the Queen’s speech debate in June, while Blair himself has called on the British public to “rise up” and change their minds over Brexit.

But there can be no stopping this process. Even if the referendum result were reversed and Britain sought to remain in the EU, it would still be impossible to simply turn the clock back to the pre-referendum state of affairs. As Wolfgang Munchau points out in the Financial Times, “once you take into account the politics of the other EU member states, an exit from Brexit is no longer an option”.

No return

There is a tendency in Britain to view the two sides in these negotiations as enlightened Europeans versus backward Brexiteers, but while there may certainly be more than a kernel of truth in this, in reality it is nothing more than a confrontation between two sets of gangsters: a “thieves’ kitchen” to use Lenin’s expression.

In or out, the UK must be made to pay. If it is able to obtain anything approaching a favourable deal then it will not be long before the likes of Italy and Spain start making their own demands. If in the process Paris or Frankfurt can snatch a slice of Britain’s vulnerable financial services sector then so much the better.

The British ruling class is therefore faced with two equally unappealing alternatives: either a “hard” Brexit takes place and the UK leaves the Single Market, with the very real risk of tariffs on British exports and the possible loss of its financial centre (in other words an economic beheading); or the UK will be forced to crawl back and negotiate an agreement in which the powers of Europe will inevitably be able to impose their own humiliating terms. Already Britain has backed down on the timetable for negotiations and the EU negotiators will force it to accept a divorce payment in due course. In the end, all roads will lead to ruin.

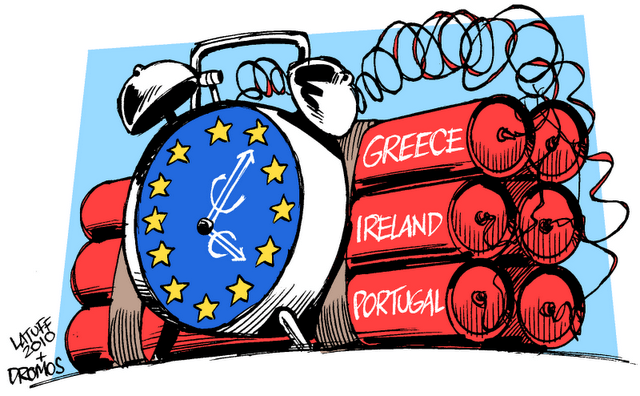

But while the British crisis may be claiming the lion’s share of the headlines at the moment, it is really only a part of the general crisis of European capitalism which grinds on to this day, despite claims of a recovery. Not one of the problems thrown up during the Euro crisis in 2009 have been solved, and despite the appearance of relative calm, the stage is being set for a fresh crisis of even greater proportions.

Zombie Europe

Despite growing at twice the speed of the UK in the last three months, the Eurozone economy is effectively sprinting to stand still. Since March 2015, the European Central Bank (ECB) has been buying “assets” from commercial banks at a rate of €60-80 billion per month, effectively providing them with free cash, in order to “support economic growth across the euro area and help us return to inflation levels below, but close to, 2%”. More than two years and €2.2 trillion later, Eurozone inflation stands at 1.4%, and it would fall back rapidly if the ECB were to turn off the tap.

Despite growing at twice the speed of the UK in the last three months, the Eurozone economy is effectively sprinting to stand still. Since March 2015, the European Central Bank (ECB) has been buying “assets” from commercial banks at a rate of €60-80 billion per month, effectively providing them with free cash, in order to “support economic growth across the euro area and help us return to inflation levels below, but close to, 2%”. More than two years and €2.2 trillion later, Eurozone inflation stands at 1.4%, and it would fall back rapidly if the ECB were to turn off the tap.

The most important reason for the failure of Quantitative Easing (QE) can be seen in Europe’s recent banking crisis. When the Italian bank, Monte dei Paschi di Siena (MPS), collapsed last year it was estimated that the “bad loans”, i.e. loans which are unlikely to be repaid, held by Italian banks amounted to €360 billion (20% of GDP). This is by no means a uniquely Italian problem either; European banks currently hold almost €1 trillion of these bad or “non-performing” loans.

This problem goes straight to the root of the European crisis. The mountain of bad loans held by European banks is a product of the underlying crisis of overproduction which continues to grip the economy. For every “bad loan” there is a small to medium-sized business barely scraping along, neither healthy enough to meet all its debt obligations nor broke enough to go into liquidation; neither alive nor dead.

According to Barnaby Martin, head of European Credit Strategy at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, the number of zombie firms in Europe is now “higher than it was pre-Lehman (Brothers)” and even “higher than it was in mid to late-2013 after the Greek saga”. Hardly a picture of a robust recovery.

Rather than addressing the problem, however, the low cost of credit maintained by ECB helps these zombie firms stagger on, while the banks use the free money provided by QE not to invest in production (why bother when you can’t expect a decent return?) but rather to speculate on the stock market, which does nothing to address the underlying crisis in the economy.

Unable to find any other solution, the Italian state has been forced to throw more than €20 billion into bailing out several failing banks, in breach of EU legislation which introduced in order to prevent another sovereign debt crisis after 2009. The response of the EU has been to endorse this “pragmatic” measure. The European Banking Authority has even proposed the setting up of a €1 trillion “bad bank”, funded by the taxpayer, to buy up the private lenders’ toxic assets.

The pattern is familiar: bad loans cause holes to appear in the banks’ balance sheets, which are then filled by states which must then implement savage cuts to sustain their already high levels of debt. The poison is simply moved around the system until it is eventually fed to workers who had nothing to do with the crisis in the first place. This isn’t just unfair; it’s completely unsustainable.

Shocks

All it took to trigger the Italian banking crisis was the stock market wobble which followed the result of the UK’s EU referendum. An even greater shock to the system could bring down the Euro and such shocks are rendered inevitable by the nature of the EU itself.

All it took to trigger the Italian banking crisis was the stock market wobble which followed the result of the UK’s EU referendum. An even greater shock to the system could bring down the Euro and such shocks are rendered inevitable by the nature of the EU itself.

Ultimately it is impossible to bind together national economies which are moving in different directions. Under capitalism, nation states are engaged in constant competition with one another. By binding them together, you simply elevate the stronger by exhausting the weaker, which in turn undermines the entire bloc.

The problem is compounded under a single currency. Prior to the creation of the Euro, weaker European economies could give themselves a slight competitive advantage against the likes of Germany by devaluing their currency. The Euro has obviously made this impossible, meaning the only way for weaker European economies to compete is by “internal devaluation”, designed to lower the price of their goods by relentless attacks on the cost of labour, i.e. permanent austerity.

There is an even deeper contradiction here. Internal devaluation naturally depresses demand and further weakens the affected economies, making it impossible for them to grow fast enough to pay their ever-increasing debts, as the soaring state debts of the likes of Greece and Italy attest. But as demand sinks in their intended markets, the exports of the dominant economies (Germany in particular) are also eventually hit. The end result is that the European whole becomes less than the sum of its parts, locked in an infernal cycle of crisis and austerity.

Ultimately this crisis is a graphic illustration of the painful limitations of the capitalist nation state, which is incapable of containing the productive forces created by its own system. The suffering and anger caused by the crisis of European capitalism is already expressing itself in increasing anti-EU sentiment in a number of countries, not least Italy, where all the failings of the European project are being brought to boiling point, including the ongoing horror of the mediterranean refugee crisis. Seen in this context, Brexit is no anomaly – it is a picture of Europe’s future.