Ukrainian Diary is the first major UK retrospective exhibition of the work of photographer Boris Mikhailov.

Traditionally trained as an engineer, Mikhailov first used a camera to document the Kharkhiv factory where he worked in the 1960s. When he was caught developing these personal photos, he was denounced, fired, and hounded by the authorities.

Mikhailov’s work centered on everyday life – but under Stalinism, anything short of glossy images of fat, happy children waving red flags was discouraged. Mikhailov was trailed, had his cameras smashed, and his film destroyed.

Undeterred, he began a lengthy photography career aimed at subverting the oppressive Stalinist norms of Soviet Ukraine. He scraped a living selling photos on the black market and became a key figure in a developing group of non-conformist photographers.

Complex reality

The exhibition focuses on over 20 of Mikhailov’s series spanning 60 years.

The series Red 1968-1978 is a standout, bringing together 70 images taken in Kharkiv, all exploding in colour.

From garish May Day rallies to vibrant every day scenes, this series smashes the notion that life in the Soviet Union was a drab, concrete Gulag. Mikhailov wanted to emphasise how deeply this colour of red – associated with blood, revolution, and communism – was steeped into every corner of life.

The contrasting series Unfinished Dissertation contains poorly printed black and white photos pasted to the back of a stranger’s tattered university thesis Mikhailov found in a rubbish bin.

These colourless, muted images – combined with the abandoned thesis document – reflect a different side of life in Soviet Ukraine: the wasted human potential and the deep loss of hope that permeated the deformed workers’ states.

Between these, a picture of the complex reality of Soviet life begins to form.

After the collapse

The exhibition is split across two floors – works made during the lifetime of the Soviet Union, and those in the years following its collapse.

After the USSR fell in 1991, Mikhailov traveled abroad, exhibiting his works across Europe. When he returned a few years later, Kharkhiv was completely transformed.

A new ruling elite of millionaires had emerged, and the population had been plunged into poverty as the old state apparatus was systematically looted. “In the streets, I noticed shadows passing: a large number of homeless people. I was shocked,” he said at the time.

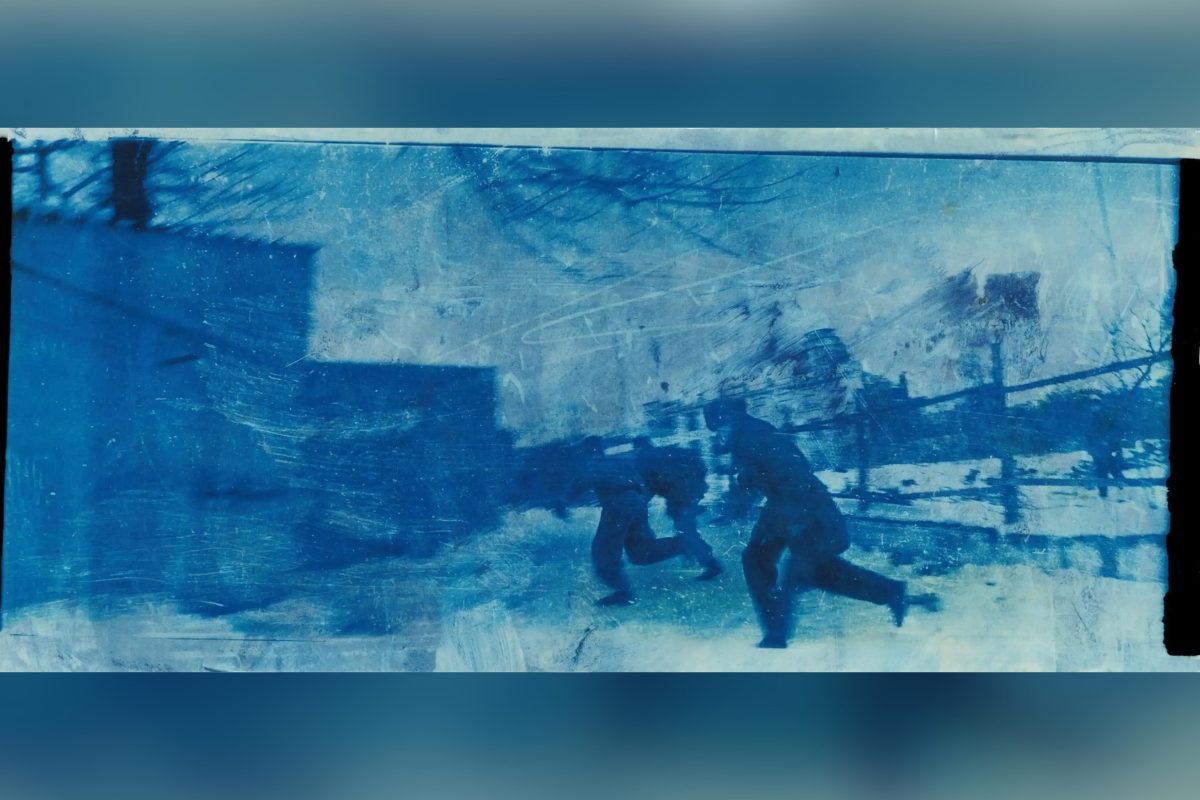

At Dusk offers wide, blue-tinted shots of Kharkiv’s streets during this time, showing people queuing for food and lying aimlessly on the street. This world resembles one destroyed by a war – a reality not unfamiliar to Boris Mikhailov. His father was enlisted in the Red Army. When the Nazis invaded, his Jewish mother got the family out on the last train out of Kharkhiv.

Discussing the unconventional use of blue as a way to convey violence, Mikhailov explained this choice in reference to this time in his life: “The colour blue to me is the colour of blockade, hunger and war. I can still remember the bombing, the wall of the sirens and the searchlights in the light blue sky.”

In the 1990s, Mikhailov was in fact witnessing the biggest collapse in living standards outside of wartime in history.

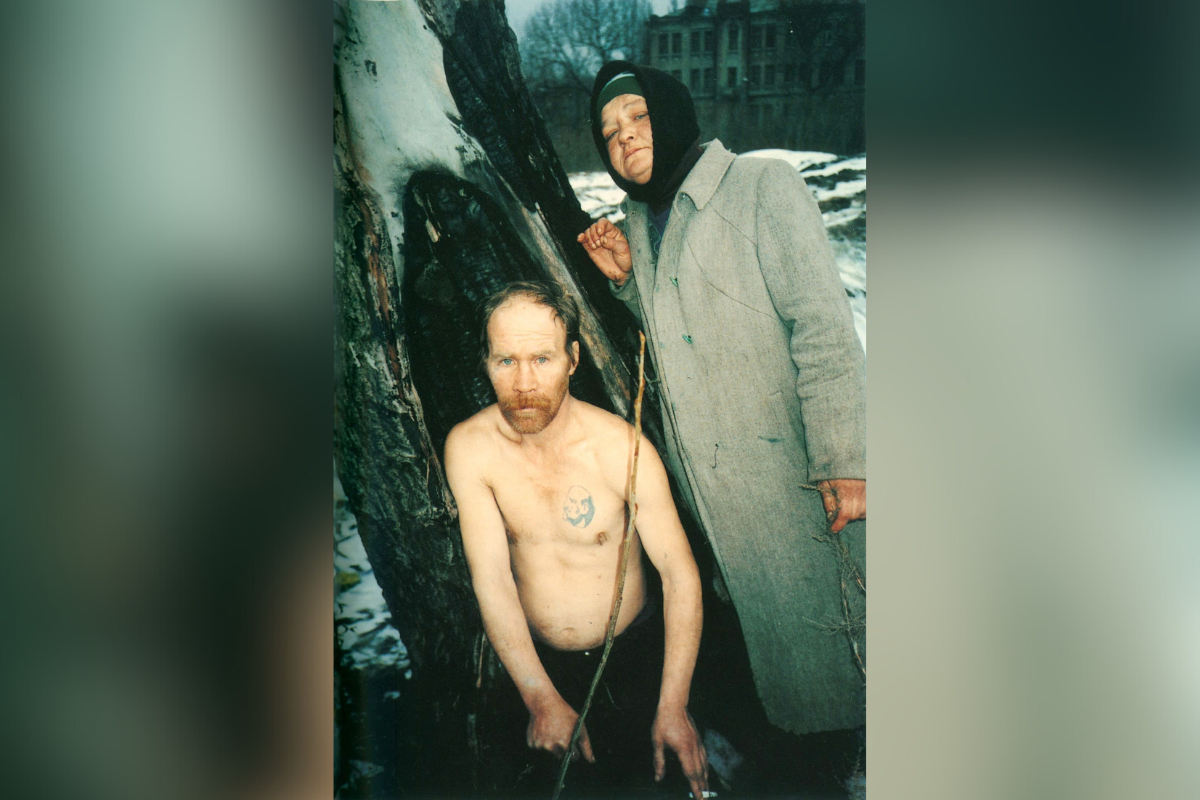

This led him to make Case History, a series of 400 unnerving portraits seeking to truthfully depict the restoration of capitalism in Ukraine. An enlarged shot from this series dominates one gallery wall: a man and woman stood outside, in the cold – the man, shirtless, displays a Lenin tattoo on his bare chest.

From Euromaidan to today

The latest series of Mikhailov’s included covers the so-called Euromaidan of 2013. Photos of the encampments prominently show fascist symbols, providing yet another indictment of what the collapse of Soviet Ukraine led to.

It’s unsurprising how little is said about this series in the gallery, besides a brief mention of this being “a prelude to the Russia-Ukraine war.”

Anti-Soviet elements latch onto the artistic repression in the Soviet Union to justify the restoration of capitalism.

It’s true you cannot point to a single well-known street photographer who reached prominence during Soviet times. The family of Masha Ivashintsova, for example, found 300,000 hidden photographs in her home when she died. These would have won her awards anywhere in the west.

But photographers like Boris Mikhailov wanted to freely take photos and exhibit them to their friends – not see the country be looted and a new billionaire class emerge.

And capitalism really offers no better for art and creativity; the hardship in the lives of ordinary people reflected in Mikhailov’s post-Soviet work are testament to this.

Today, there are doubtless millions of Boris Mikhailovs and Masha Ivashintsovas stuck wasting their lives away in factories and warehouses – or dying in wars to secure the capitalists’ profits.

We can only begin to imagine the artistic potential waiting to emerge in a world freed from the shackles of profit, private property, and war.

‘Boris Mikhailov: Ukrainian Diary’ is showing at The Photographers’ Gallery London until 22 February 2026.