I just finished a four year stint in art school, where I exclusively developed an explicitly political practice.

Yet I’d never encountered the work of Peter Kennard – ‘artist, activist, and the UK’s first (and only) Professor of Political Art’ – before strolling through the glass doors of Whitechapel Gallery on a rainy Tuesday evening to see his current exhibition, Archive of Dissent.

I am greeted by an italicised disclaimer reading: “artworks in this exhibition make reference to and feature images of war (past and current), violence and political protest“.

The slanted voice of the institution stands in contrast to the work on display. Do they really believe that we are not already bombarded by horrific images and reports of war, violence and genocide on a daily basis?

Perhaps they are knowingly speaking to the privileged audience of the blue-chip art world who can turn a blind eye to the horrors of the world – who, I am convinced, would not appreciate Archive of Dissent.

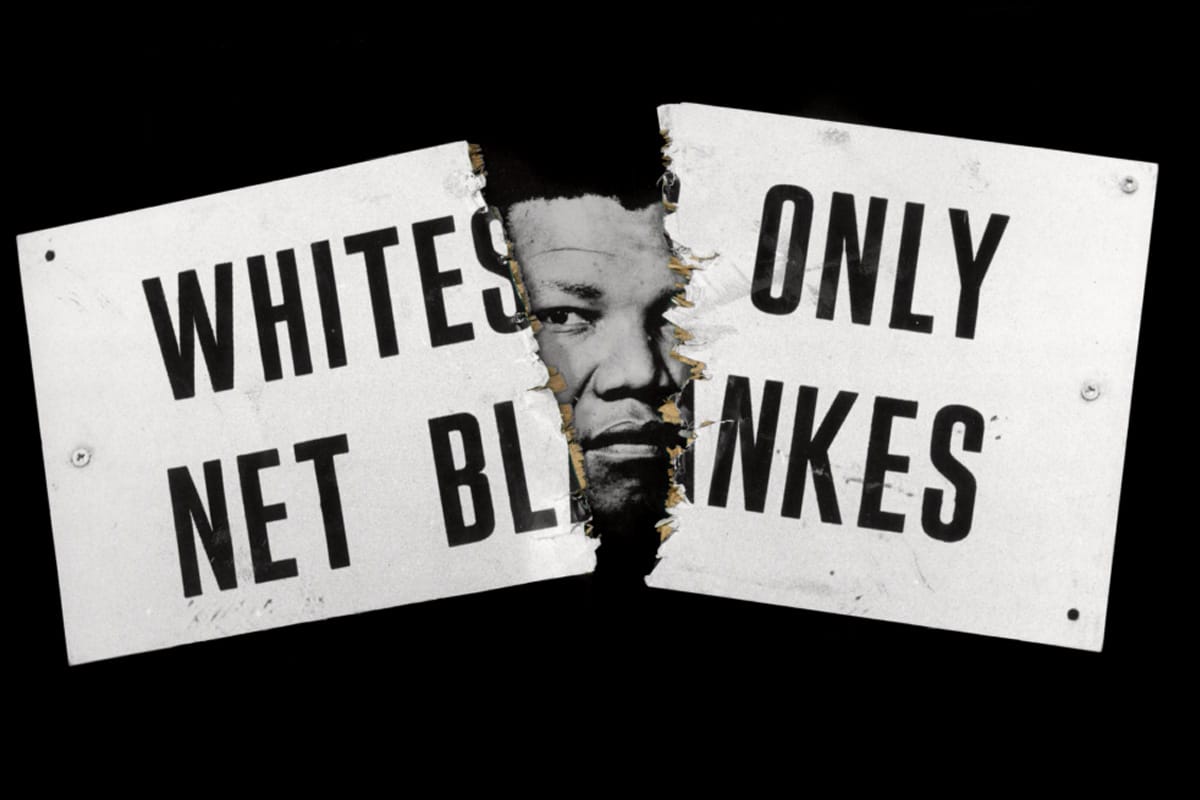

This is an exhibition which, in Kennard’s own words, unapologetically “unmasks the connection” between the profit-drive of capitalism and “poverty, racism, war, climate catastrophe”.

Voir cette publication sur Instagram

Archive

The exhibition is made up of three rooms, the first of which consists of a library space and collection of political posters. I make a beeline for the books first, all of which have been published by Kennard.

I immediately appreciate the true-to-title staging of the exhibition as an archive: it feels as though effectively all of Kennard’s major projects (books, posters, installations – even his desk!) are included for your consideration, creating a full picture of the extent and range of his work.

For an exhibition, this makes some of the imagery a little repetitive as you sift through decades of posters for rallies and meetings and demonstrations. Almost all feature the same imposing skull collage; a key image for the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

When you look at the exhibition as an archive, however, this documenting of anything and everything (especially posters which were intended to be ephemeral) adds a lot of richness and depth.

For me, the highlight of this first room was Kennard’s book About Turn: Alternative Use of Defence Workers Skills, which includes Kennard’s photomontages alongside details of the Lucas Plan.

Thumbing through a dog-eared copy, I learn that in 1974, when Lucas Aerospace announced cuts to jobs, the workers spent two years developing a plan through which weapon plants were transformed into factories for socially-useful goods.

Though the plans were never implemented, the Lucas Plan included cutting-edge green technologies, revealing the full potential of society if only the means of production were democratically planned.

People’s University

The second room features Kennard’s desk, charcoal drawings on newspapers, and a new, site-specific work, titled People’s University of the East End.

Consisting of a number of placards behind blue and white police tape, this new work is an ode to the radical history of the Whitechapel area and the building’s past as a library from 1892-2005.

The exhibition text explains how this library acted as a “sanctuary” for poverty-stricken Eastenders, as well as “a place to develop radical and dissident ideas about art, literature and politics.”

Voir cette publication sur Instagram

I take note of one placard, right near the front, which features a Palestinian flag where the red is bleeding into the white of the flag.

It is the first time I have seen anything that explicitly deals with Palestine in an art gallery.

Usually, I am reading about how Arts Council England continues to censor political art, or how the likes of the Royal Academy have omitted Gaza-inspired works from their public exhibition.

I feel as though Kennard has managed to sneak the anger so many of us feel through the gaps of the art world’s telling silence – bringing into the gallery a sense of those instances of solidarity that take place most-often outside of it, on the streets.

Transience

Finally, I make my way into the last room. I am greeted by walls of newspapers, flashing lights, and photomontages.

I am intrigued by an installation of Financial Times newspapers, which are sporadically illuminated by warm yellow lights to reveal Kennard’s photomontages of wars, poverty, and climate destruction.

My eyes follow the beat of a Raspberry Pi computer, working hard behind the scenes, which turns on multiple bulbs to illuminate various drawings, before switching to another configuration.

I can’t spend too long scrutinising any one drawing before another is lit up. It evokes both the transient forms much of Kennard’s work takes, and the speed at which these issues are spotlighted and then forgotten again by the media cycle.

I spend some time, too, with the photomontages, for which Kennard is known best.

My favourites are two Thatcher-era works: one that depict Ms Thatcher as a skull – or Dr Death, in my mind – and a second that juxtaposes hospital signage with a ‘CLOSED’ sign, as a dilapidated person is hunched over, small and weak, in a bed.

These images do not spark joy, of course, but they speak the truth.

As Kennard intends, they unmask the connection between parliamentary politicians and the system they serve at the expense of the rest of us. If I wasn’t already organised, such images would stand as a call to action.

Dissent

Overall, Archive of Dissent is an impressive collection of the work Kennard has produced across a fifty year career. His approach to photomontage is indubitably skilled, and I can’t help but question why Kennard’s practice was so easily omitted from my own arts education.

Nevertheless, it is no coincidence that Kennard is getting his flowers afresh now. As conflict continues to ravage our world, the anti-war and anti-capitalist sentiment captured within Archive of Dissent is contagious.

We need more art like Kennard’s: art that tells the truth, that deals with the biggest and ugliest questions in life, and that can be appreciated – in exhibitions, or on the streets – by the many, not just the few.

‘Archive of Dissent’ is on show for free at the Whitechapel Gallery until January 2025.