This month marks the 200th anniversary of the official abolition of slavery and the passing of the Slave Trade Act, which made the capture, and transport of slaves by British subjects unlawful.

While slavery itself remained legal in the Empire until 1834, the Act marked the effective winding down of a 250-year old trade in human life, not just in Britain but amongst all countries. Slavery is remembered for its almost unimaginable brutality, of the forced transport of people from West Africa to the Americas, and after surviving that ordeal, the terrible conditions of slave labour on the plantations. Unknown numbers of people – according to some estimates at least 4 million – died in slave wars and forced marches. More perished on the voyages across the Atlantic.

The slave trade inflicted tremendous suffering on millions of people – this much is clear, and should not be forgotten. Viewed from a world historical perspective, its importance in shaping the modern world goes far beyond a sorry story of human misery and suffering. For the rising bourgeoisie, especially in Britain, the slave trade played a pivotal role in the expansion of the global market and the creation of the modern world capitalism. In the words of Marx, capitalism was born "dripping with blood from every pore."

British involvement in the trade began around the middle of the sixteenth century, where rich merchants and pirates rushed to capitalise on the trade. In its formative years, Africans were captured and made into slaves by raiding parties from the ships that were to transport them across the Atlantic. Later, this became the first side of the "triangular trade"- manufactured goods from Europe being traded for slaves already held in Africa. Hundreds of thousands of firearms were imported to Africa, and the rivalries of Europe were translated into wars between the kingdoms and chiefdoms of African tribes. Such imperialist meddling greatly increased the supply of slaves, which, of course, cheapened the cost of these human commodities. As Marx explained, capitalism is first and foremost the production of commodities, and slaves became regarded as commodities in much the same way as shoes.

Dilemma

Confronted by the power of the European capitalist nations, those Africans who collaborated in the slave trade were faced with the dilemma: either provide slaves or become slaves themselves. Having transported their human cargo to the Americas, the slavers would return home with the products of slave-labour such as sugar, tobacco and cotton. Liverpool became a key port for the slave trade in Britain.

Slaves were considered the property of their owners. They had no rights or liberties as human beings. They were simply treated as work horses by their owners. As property of their owner, they had to be "maintained" – kept alive and in a suitable condition to work. But slave labour, although profitable, had its limits – a factor which would come in to play as time wore on. Slaves who simply received their subsistence, the lowest reward for their labour power, were also the least productive and had the shortest life span. As things stood the average life expectancy of a plantation slave was only 7 to 10 years. But work on the giant plantations of the Americas was suited to such labour. The indigenous labour force had been largely exterminated by disease and the bloodlust of the imperialist invaders so there was a ready demand for humans who could do the terrible work required of them by the new plantocracy. Of course, escape had to be deterred – slaves could not be put to work too near their homelands. So crossing the Atlantic was a long but necessary journey for the slave traders. Although, the costs of their transport were high, with many losing their lives on the arduous journey, their sweated labour was sufficient to make handsome profits for their new owners. Nevertheless resistance and revolt on the part of the slaves would be common throughout the whole history of slavery – an heroic struggle largely airbrushed out of official histories which would concentrate instead merely on the do-gooders campaign back in England as the main factor in the abolition of the slave trade and later slavery itself. These revolts would always be suppressed with a brutality and sadism beyond anything you would think possible from so-called civilised people. That slaves would continue to rebel is a testimony to their courage and bravery in the face of insurmountable odds. The great Haitian revolution of 1791 in the French colony of St. Domingue, led by Toussaint L'Ouverture (and brilliantly described in C.L.R. James' classic work 'The Black Jacobins) remains the most famous of such uprisings.

The bare statistics of slavery are appalling but sometimes it is more telling to concentrate on a single story. William Wells Brown was born in Kentucky in 1814 and worked on a series of plantations before he escaped. He relates a glimpse of the humiliating life of a slave and his family. "A woman was also kept at the quarters to do the cooking for the field hands, who were summoned to their unrequited toil every morning, at four o'clock, by the ringing of a bell, hung on a post near the house of the overseer. They were allowed half an hour to eat their breakfast, and get to the field. At half past four a horn was blown by the overseer, which was the signal to commence work; and every one that was not on the spot at the time, had to receive ten lashes from the negro-whip, with which the overseer always went armed. The handle was about three feet long, with the butt-end filled with lead, and the lash, six or seven feet in length, made of cow-hide, with platted wire on the end of it. This whip was put in requisition very frequently and freely, and a small offence on the part of a slave furnished an occasion for its use.

Mr. Cook

"During the time that Mr. Cook was overseer, I was a house servant — a situation preferable to that of a field hand, as I was better fed, better clothed, and not obliged to rise at the ringing of the bell, but about half an hour after. I have often laid and heard the crack of the whip, and the screams of the slave. My mother was a field hand, and one morning was ten or fifteen minutes behind the others in getting into the field. As soon as she reached the spot where they were at work, the overseer commenced whipping her. She cried, "Oh! pray – Oh! pray – Oh! pray" – these are generally the words of slaves, when imploring mercy at the hands of their oppressors. I heard her voice, and knew it, and jumped out of my bunk, and went to the door. Though the field was some distance from the house, I could hear every crack of the whip, and every groan and cry of my poor mother. I remained at the door, not daring to venture any further. The cold chills ran over me, and I wept aloud. After giving her ten lashes, the sound of the whip ceased, and I returned to my bed, and found no consolation but in my tears. Experience has taught me that nothing can be more heart-rending than for one to see a dear and beloved mother or sister tortured, and to hear their cries, and not be able to render them assistance. But such is the position which an American slave occupies."

The development of British capitalism was partly financed by the profits from the slave trade where it would long enjoy a monopoly. Britain was one of the first to enter the road of capitalist development and established herself as a world power as a result. The British Empire was a tremendous source of raw materials, including slaves, and a ready made market for British goods. The British ruling class was nevertheless very concerned about Africans obtaining too much knowledge for fear that they may become competitors. In 1751 the British Board of Trade advised the Governor of Cape Castle (a trading settlement and fort where slaves would be held prior to transit):

"The introduction of culture and industry among the Negroes is contrary to the known established policy of this country, there is no saying where they might stop, and that it might extend to tobacco, sugar and every other commodity which we now take from out colonies; and thereby the Africans, who now support themselves by wars, would become planters and their slaves be employed in the culture of these articles from Africa, which they are employed in America."

New market

The slave-trade gave a huge new market to a trade that already existed. There were massive fortunes to be made. John Hawkins, one of the first British slave traders returned home an extremely rich man. Later slaver traders provided returns of 50-100% or more on investments. The nature of the cargo being transported, human beings, and the uncertainties of supply, meant that profitability sometimes fluctuated, but was still higher than domestic returns. Much of the British ruling class were at least indirectly involved in the slave trade. Through the holding and dealing of shares in slave trading companies, ports such as Liverpool, Bristol, Portsmouth and Lancaster, built their regional influence and economic importance on the existence of the trade. Those companies that participated in the slave trade were an important part of the industrial revolution that took place in Britain – the gains made on the trade were ploughed back into other industrial enterprises. Marx wrote that:

"It is slavery which has given value to the colonies, it is the colonies which have created world trade, and world trade is the necessary condition for large-scale machine industry. Consequently, prior to the slave trade, the colonies sent very few products to the Old World, and did not noticeably change the face of the world."

Although the slave trade was abolished 200 years ago, slavery still continued in many parts of the world, including the United States, where it would remain in the southern states up to the Civil War. It played its part in the "primitive accumulation" of capitalist development. The tendency has always been to present the abolition of the slave trade as yet more evidence of the 'basic decency and morality' of the British character and, by extension, the British Empire.

Abolitionist movement

We should not forget, of course, the huge pressure that was brought to bear on the British state by the abolitionist movement, both at home and in the colonies – a movement which included many radicals. But we should also be clear that abolition was largely a commercial decision made by a class which invariably considered the 'lower orders' as a workshy bunch worthy only of pity at best, contempt at worse. They had become tired and frightened of the constant threat of slave revolution in their colonies but also saw the new opportunities available to them. As A.L.Morton notes in his classic work 'A People's History of England' (available online from Wellred Books): 'Profitable as the slave trade proved during the 18th century, its suppression in the 19th century was even more profitable.' Few tears were shed by the ruling class for the loss of the slave market in the West Indies since slavery there was becoming uneconomic anyway as the plantation owners turned instead to the almost equally brutal but cheaper (and for them safer) practice of wage slavery in which workers were paid a pittance for their sweated labour. The great slave revolt of 1831 in Jamaica (following on from those in Barbados in 1816 and Demerara in 1823) was the last straw for an already heavily outnumbered and beleaguered white settler population. Where forced labour was still required the 'exporting' of prisoners remained an option for Britain, France and others. The military forces of the British empire now set to work on the 'moral task' of hunting down slave traders and in doing so, of course, also set about invading and conquering the interior of Africa redrawing the maps in their interest. The ruthless and bloody exploitation of that continent had begun. As Perfidious Albion tightened its grip also on India, Arabia and the Far East, so begun the great century of intrigue, divide and rule, brutality and occupation which would obsess all the great European powers including France, Belgium but most of all Britain. The effects of this are still being felt today. No wonder the great Chartist writer Ernest Jones would be moved to write in 1851 about the British Empire: ' On its colonies the sun never sets, but the blood never dries.'

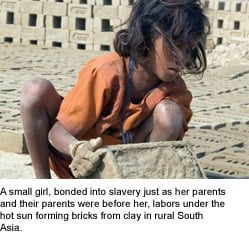

Slavery still exists

Today, slavery takes many forms. The traditional form of slavery still exists of course in many parts of the world, hidden from view but there nevertheless. Forced labour (including that of children) remains common in countries such as Pakistan, despite the supposed protection of the law and a raft of useless international declarations. The scourge of human trafficking and forced prostitution have become an extremely profitable enterprise, especially with the re-introduction of capitalism in Russia and Eastern Europe. Marx explained that while chattel slavery was officially abolished, wage slavery become the dominant form of exploitation under capitalism. Workers no longer own the means of production and are forced to sell their labour power from week to week. Few are able to escape from this relationship. While the slave trade has been partly abolished, the task now before us is to abolish wage slavery by the overthrow of capitalism and the construction of a socialist society. Only then will humankind become really free.

Today, slavery takes many forms. The traditional form of slavery still exists of course in many parts of the world, hidden from view but there nevertheless. Forced labour (including that of children) remains common in countries such as Pakistan, despite the supposed protection of the law and a raft of useless international declarations. The scourge of human trafficking and forced prostitution have become an extremely profitable enterprise, especially with the re-introduction of capitalism in Russia and Eastern Europe. Marx explained that while chattel slavery was officially abolished, wage slavery become the dominant form of exploitation under capitalism. Workers no longer own the means of production and are forced to sell their labour power from week to week. Few are able to escape from this relationship. While the slave trade has been partly abolished, the task now before us is to abolish wage slavery by the overthrow of capitalism and the construction of a socialist society. Only then will humankind become really free.