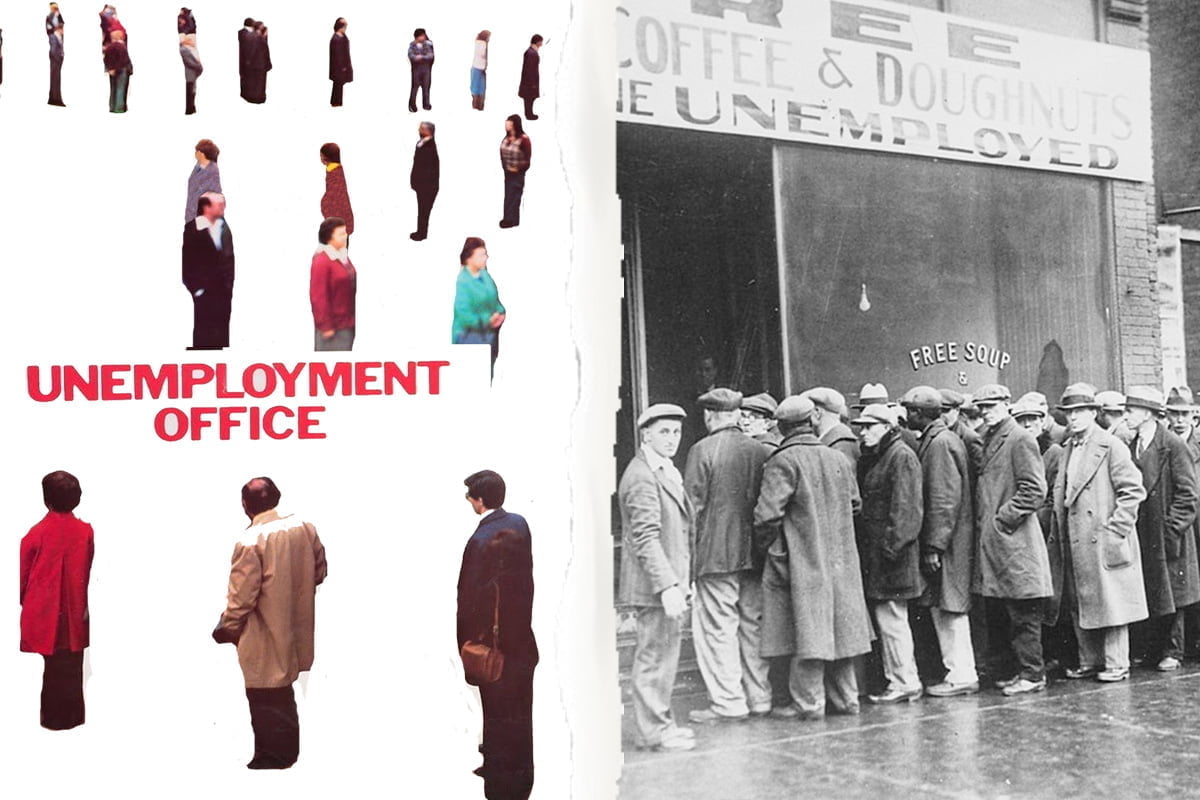

The coronavirus pandemic has exposed the underlying contradictions of capitalism, triggering a deep crisis on the scale of the 1930s. There will be no rebound after the lockdown ends, but a prolonged economic depression.

The world has been turned upside down and inside out by the coronavirus pandemic. We have truly gone through the looking glass.

The market system is in meltdown. The laws of capitalism have broken. With production paralysed, supply has collapsed. But with people locked indoors, so has demand. The ‘invisible hand’ doesn’t know which way to point.

For the first time in history, oil prices have turned negative. Interest rates – already at rock-bottom levels – are now also below zero in many economies, in real terms. And the boundary between monetary policy and fiscal policy has dissolved, as central banks and governments unite to prop up the imploding edifice of capitalism.

Those who previously preached about the ‘efficiency’ of the free market are now demanding the most extreme measures and state intervention to save capitalism. The covid-19 crisis is even “turning Tories into socialists”, according to Conservative journal The Spectator.

The ruling class is pumping trillions into the global economy. Bankrupt big businesses are demanding bailouts. And ideas such as a ‘helicopter drop’ of money, once scoffed and scorned, are now being openly considered by the serious strategists of capital.

But even this is not enough. The economy is in freefall, dropping faster and deeper than even the 2008 crash. Unemployment is skyrocketing, with over 30 million (officially, so far) thrown out of work in the USA alone. Comparisons with the Great Depression are no exaggeration. If anything, they are an understatement.

After all, the world’s population – and working class – are far larger now than in the 1930s. And, importantly, the world economy is more integrated than ever before. In short, what we are facing today, unlike any slump previously, is a genuinely global crisis of capitalism.

Hope springs eternal

Yet hope springs eternal in the capitalist breast. ‘Surely this is all just a temporary blip?’, Mr Moneybags and his banker chums suggest. Hence the optimistic projections of a ‘V-shaped’ recovery: a sharp fall in economic activity during the lockdown, followed by a vigorous rebound afterwards.

Yet hope springs eternal in the capitalist breast. ‘Surely this is all just a temporary blip?’, Mr Moneybags and his banker chums suggest. Hence the optimistic projections of a ‘V-shaped’ recovery: a sharp fall in economic activity during the lockdown, followed by a vigorous rebound afterwards.

There is no doubt over the first part of this prediction. US GDP is already predicted to contract by around one-third in the second quarter of this year, at an annualised rate; and by over 5% for 2020 as a whole. Similar estimates have been made for the UK economy and for Europe also.

The second half of this equation is not so certain, however. After all, there are many other letters in the alphabet when it comes to describing capitalism’s curves.

Some have talked of a ‘U-shape’, with a long downturn and an eventual upswing. Others have thrown in the letter W, representing a ‘double-dip’ recession – a distinct possibility if there is a second-wave outbreak of the virus. An ‘L’, representing a new depression, has also been ominously mentioned. Some have even warned of an ‘I’: a straight plummet without end!

So which of these, if any, are the most likely scenario? And what is the rosy ‘V-shaped’ picture of the capitalists based on?

This forecast of rapid recovery is based on the same idealistic assumption that has always motivated the apologists of capitalism: the omnipotence of the market, and their unbridled faith in it. Added to this, is a belief that the current social distancing measures are merely a transient phase.

Yes, we may be plunging right now, the more sanguine capitalists say. But the disease will soon be under control, and ‘normality’ will return. Then the economy will reopen, like an animal emerging from hibernation, full of zeal, and the merry money-making can begin again.

Indeed, the most libertarian voices have even welcomed the covid-19 crisis for providing a burst of Schumpetarian ‘creative destruction’.

This is clearly the position being pushed by President Trump in the USA, who has asserted that “the cure cannot be worse than the disease”. And the same callous line is being peddled by a wing of the Tory Party in Britain, representing the interests of big business, who have no qualms about putting profits before lives.

Economic contagion

The reality, however, is that the world economy will not bounce back. The pandemic will leave a permanent scar. When capitalism collapses, it does not simply hit the pause button. Rather, industries being mothballed and workers being furloughed today – ‘temporarily’ – may never again see the light of day.

The reality, however, is that the world economy will not bounce back. The pandemic will leave a permanent scar. When capitalism collapses, it does not simply hit the pause button. Rather, industries being mothballed and workers being furloughed today – ‘temporarily’ – may never again see the light of day.

Like the coronavirus itself, “economic distress is contagious, too”, writes economist Tim Harford in the Financial Times. And “the economic cost of lockdowns also grows exponentially”.

“One day’s lockdown is little more than a public holiday,” Harford continues. “Two weeks’ lockdown threatens those who are already in a precarious position. Three months’ lockdown can do widespread damage that lasts for years.”

There is little evidence to suggest that pent-up demand will burst to the surface once the lockdown is lifted. Tourism, retail, and entertainment may all never be the same again. Around 60-70% of people, for example, have said they are unlikely to book a holiday in 2021, due to both economic and health concerns. Only 20% believe that they will hit the shops immediately once (if) they open again.

Elsewhere, with airlines practically falling out of the sky, turning to governments for bailouts, the future of the entire aviation industry is being brought into question. Ditto with the oil sector – particularly in America, where investors have poured billions into shale oil production over the last decade. Now, with demand and prices crashing, US oil companies face an existential threat.

The same is true for the world’s giant car manufacturers, many of whom were already struggling prior to the coronavirus outbreak. Firms like Fiat Chrysler are set to go bust after just three months of shutdown. Others, like Ford and Renault, are only a few months behind. And one must not forget that all of these industries not only employ millions directly, but also provide business for a vast network of suppliers.

At the same time, an army of ‘zombie’ businesses has been kept half-alive by a lifeline of permanent cheap credit in recent years. This new slump could finally bury them. Banks are already bracing themselves for the ensuing contagion of debt defaults that would spread through the financial system. And bubbles are bursting everywhere, as investors retreat from riskier ventures, seeking a safe-haven in hard cash.

Organic crisis

Capitalism is not a yo-yo. The economy cannot simply go down and then up. There are times when such recessions do occur, representing the rhythmic breathing of the capitalist ‘business cycle’. But this crisis – coming on the back of the deep 2008 slump – is clearly not such a time.

Capitalism is not a yo-yo. The economy cannot simply go down and then up. There are times when such recessions do occur, representing the rhythmic breathing of the capitalist ‘business cycle’. But this crisis – coming on the back of the deep 2008 slump – is clearly not such a time.

Rather, we are in an epoch of capitalist decay, facing an organic crisis of capitalism: one in which the system is caught in a vicious downward spiral; where falling employment leads to falling demand – which in turn leads to falling investment, and thus a further fall in employment, and so on and so forth.

Furthermore, unlike the 2008-09 crash, the crisis today is a truly global one. Back then, as Martin Wolf succinctly explains in the FT, China was able to register record growth levels on the basis of carrying out an enormous programme of Keynesian spending. This, in turn, pulled up the economies of major commodity exporters – such as Brazil and South Africa – and of oil producers too.

But now, as a result, China is drowning in debt. Like their counterparts everywhere, the leaders in Beijing have run out of ammo to fight this crisis. And even with the quarantine over (for now), the Chinese economy still faces a rocky road ahead. After all, with the rest of the world still in a state of suspension, who is going to buy any Chinese exports?

The same problem faces every other country in reverse. Even if business were to resume, how can America or Germany hope to recover unless they have a market elsewhere for their goods?

Under capitalism, we see, the fate of each country is linked to every other. As the American Founding Father Benjamin Franklin correctly stated: we must all hang together, or, most assuredly, we shall all hang separately.

The current slump, then, is no mere ephemeral episode. Rather, it represents a fundamental turning point in world history; in the development – and decline – of capitalism. This hard truth, if it hasn’t already, will soon burn itself onto the brains of even the most thick-skulled of the capitalist class. And it is a revolutionary reality that we, the Marxists, must fully recognise also.

Inflation, deflation, or chaos?

In their efforts to save the system, the capitalist class are throwing out decades – nay, centuries – of free market orthodoxy. State intervention is the order of the day.

In their efforts to save the system, the capitalist class are throwing out decades – nay, centuries – of free market orthodoxy. State intervention is the order of the day.

Across the world, governments are becoming the ‘lenders, borrowers, and spenders of last resort’, protecting banks and big businesses, and propping up the whole economy. Once again, it seems that “we are all Keynesians now”.

Government debt is ballooning, as policy makers throw the proverbial kitchen sink at the problem. The IMF predicts that total public debts will increase by $6 trillion this year in the advanced capitalist countries – a rise from 105% of GDP to 122%.

But desperate times call for desperate measures. And others are proposing ideas that only months ago would have been considered anathema. Amongst these is the suggestion that government debt could be financed directly by central banks.

Normally, national debt is sold on the market in the form of bonds; and governments need to find willing creditors. But in such times of need, they are willing to skip out the middlemen, and get the Fed, the Bank of England, etc. to hoover up government bonds themselves.

How is this to be financed, one might rightly ask? In plain speak: by printing money.

This has understandably raised question marks over the threat of inflation. After all, the bourgeoisie themselves never miss an opportunity to point the finger at the bogeyman of Venezuela, where attempts to finance public spending through the creation of new money has led to rampant hyperinflation.

True, all other things being equal, a mass injection of cash into the economy should cause inflation. As Marx explained, money is ultimately a representation of value – the value of commodities in circulation. If there is more money chasing the same amount of goods (or fewer), then there will be a generalised rise in prices, i.e. inflation.

But right now, as emphasised above, clearly all other things are not equal. Countervailing forces are at play – most notably, the huge slump in demand that has occured due to the global lockdown. Supply may be restricted, but demand is falling even faster. This acts as a massive downward pressure on prices.

Negative oil prices are the most acute expression of this. But with the exception of some vital goods (such as food), prices are falling in general, as the market shrinks and competition intensifies.

Industries across the board are set to collapse. Mass unemployment will hasten the race to bottom in terms of wages and conditions. A depressive downward spiral is already setting in. Many of the more far-sighted representatives of the capitalist class, therefore, are far more fearful of deflation in the long term than of inflation.

It is also important to remember that in this day-and-age, the money supply is not predominantly determined by central banks. They are only in charge of setting the ‘base’ supply. The vast bulk of money in the economy in fact comes in the form of credit, created by private banks in response to demands from businesses and households for loans and mortgages.

But with ‘effective demand’ – in the form of investment and consumption – falling, the demand for credit is rapidly diminishing too. In other words, the money publically created by central banks is a futile attempt to overcome the collapse in money privately created by the banking system.

Overproduction

Quantitative Easing (QE) involves a similar process to the newly proposed bond purchasing by central banks. But instead of central banks buying up government bonds directly, under QE they create money to buy such assets from the banks, thus freeing up capital that could be used to lend to businesses in the real economy.

Quantitative Easing (QE) involves a similar process to the newly proposed bond purchasing by central banks. But instead of central banks buying up government bonds directly, under QE they create money to buy such assets from the banks, thus freeing up capital that could be used to lend to businesses in the real economy.

Or so the theory goes. In reality, this additional QE cash has never made its way into the real economy – hence, generally, the lack of inflation across the world over the last decade.

Instead, the banks just sat on the extra money, using it to boost profits. And with no profitable avenues for investment anywhere, asset bubbles were inflated and stock markets frothed, with speculation and share buy-backs rife.

This failed experiment only goes to show, as the old saying states: you can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink. Governments (via central banks) can print all the money in the world – but they can’t force the capitalists to invest it.

Capitalism is a system of production for profit. The capitalists will only invest if it is profitable to do so. And for over a decade now, the world economy has been chiefly characterised by a glut of commodities, of idle corporate cash reserves, and of ‘excess capacity’.

In other words, business investment is at historically low levels, not because of a lack of money (‘liquidity’), but due to the capitalist system’s crisis of overproduction. And far from subduing this, the pandemic is set to exacerbate all these existing tensions.

As the lockdown subsides, however, the danger of inflation in certain areas could raise its head. Right now, with shops shut and industry suspended, the money being thrown into the economy has nowhere to go. Much will be saved for the future, when businesses reopen. This could lead to a surge in spending further down the line.

But with production restarting in a sporadic and uneven way, global supply chains shattered, and the likely emergence of protectionism, this increased demand could hit up against a wall of restricted supply. Inflation in some sectors could well ensue.

Similarly, if governments everywhere pursue deficit financing and expansionist policies indefinitely, then this too will eventually lead to inflation – and even hyperinflation – as artificially enlarged demand clashes with the limits of capitalism’s productive forces.

It is impossible to say exactly how things will pan out in practice. Marxist economic theory is no crystal ball, but a dialectical and materialist analysis of the dynamic, complex, and contradictory system that is capitalism.

What we can say for certain is that any vestiges of stability will quickly evaporate. Volatility and turbulence are the ‘new normal’ when it comes to the world economy. Bouts of inflation will be layered on top of a general picture of depression and deflation. The overriding feature will be one of capitalist chaos.

No free lunch

Whilst they are all happy to throw money at the crisis in the immediate term, the more serious capitalists also know that there is no such thing as a free lunch. Government debts accumulated now will have to be paid back in the not-so-distant future – and with interest. Someone will have to pay for this crisis.

Whilst they are all happy to throw money at the crisis in the immediate term, the more serious capitalists also know that there is no such thing as a free lunch. Government debts accumulated now will have to be paid back in the not-so-distant future – and with interest. Someone will have to pay for this crisis.

In a recent editorial, The Economist outlines the options facing highly leveraged governments across the world. In summary, the liberal journal concludes, debts will have to be tackled in one of three ways: through taxes; through inflation; or through default.

The example of the Second World War is cited, when Britain emerged with a national debt equivalent to over 270% of GDP. Back then, a combination of inflationary policies and increased taxes were utilised to decrease debts to below 50% of GDP. Unprecedented growth also helped, by reducing the burden of the debt relative to the size of the overall economy.

The article proposes deploying a similar economic arsenal today. But as liberals always do, the magazine’s authors avoid the political question at the heart of this choice: Who pays?

None of three suggested prongs of attack is ‘neutral’. At the end of the day, there is a class question to answer. Taxes, for example, are not abstract numbers. They must fall either on the capitalist class or the working class. But the former deters business investment; the latter bites into consumption.

Similarly with defaults. After all, who owns the debt that is to be defaulted on? Again, either it is the capitalists, who hold government debt as part of a basket of investments. Or it is workers, in the form of pension pots and other lifetime savings.

The same with inflation, which by the Economist’s own admission, “would bring arbitrary redistributions of wealth to the disadvantage of the poor”.

At the same time, we must stress that the economic outlook for after the pandemic is not one of growth. There will be no repeat of the postwar boom, which arose out of an unprecedented concatenation of factors that will not be repeated today.

Indeed, debts – public and private – were already at eye-watering levels before the covid-19 crisis. As households, businesses, and governments repay these accumulated debts of the past, it saps into demand going forward.

In turn, as discussed above, depressed demand weighs down on prices, leading to potential deflation. And diminished consumer demand also means anaemic growth – if any. And all of this acts to increase the real value – and burden – of debt.

Class struggle

This looming maelstrom will come on top of a tsunami of attacks on the working class. Automation is likely to increase in the wake of the pandemic, for example, as businesses look to reduce their reliance on workers, creating anxieties about a ‘race against the machine’.

And international competition between workers will intensify, as the global labour market expands on the back of an increase in remote working, videoconferencing, and other new workplace communication technologies.

Without an equivalent pay rise, meanwhile, workers would see a real decline in their wages as a result of any inflation. This would lead to a wave of industrial strikes and struggles, as workers looked to claw back what they had lost.

This – the intensification of the class struggle – is the perspective that is missing from the vague assessments of the liberal commentators. Although even the Economist’s out-of-touch journalists are reluctantly forced to conclude that: “One way or another, the bills will eventually come due. When they do, there may not be a painless way of settling them.”

In the final analysis, society is divided fundamentally into classes. Either the capitalist class or the working class will have to pay for this crisis. And the ultimate outcome will not be determined by economic equations or think-tank blueprints, but by a battle of living forces.

We call on you to join us in the battle, on the side of workers and youth, to fight for a socialist future.