The Bristol Bus Boycott, which lasted from 29 April to 27 August in 1963, came to a close 60 years ago. Inspired by the example of Rosa Parks in the United States in 1955, this community-led struggle marked a milestone in the fight against racial discrimination in British workplaces.

The boycott was a significant stepping stone in the British Civil Rights movement, challenging the Bristol Omnibus Company’s adoption of the notorious ‘colour bar’ in its employment practices.

This saw black and Asian workers refused work point-blank – a ‘red line’ that many bosses across the country would not cross for their own cynical ends.

This policy was defended by Ian Patey, general manager of the Bristol Omnibus Company, who argued that his staff would not mix with “coloured labour”.

Patey’s brazen racism, covered in the Bristol Evening Post for all to see, lit the fuse of anger amongst the local Caribbean community, demonstrating clearly that they had been brought to the ‘mother country’ on false pretences.

This prepared the grounds for a social explosion against the despicable discrimination in housing, education, and employment that was widespread in Britain at the time – and which is still prevalent today, decades later, despite all the hard-fought gains that have been won since.

Divide and rule

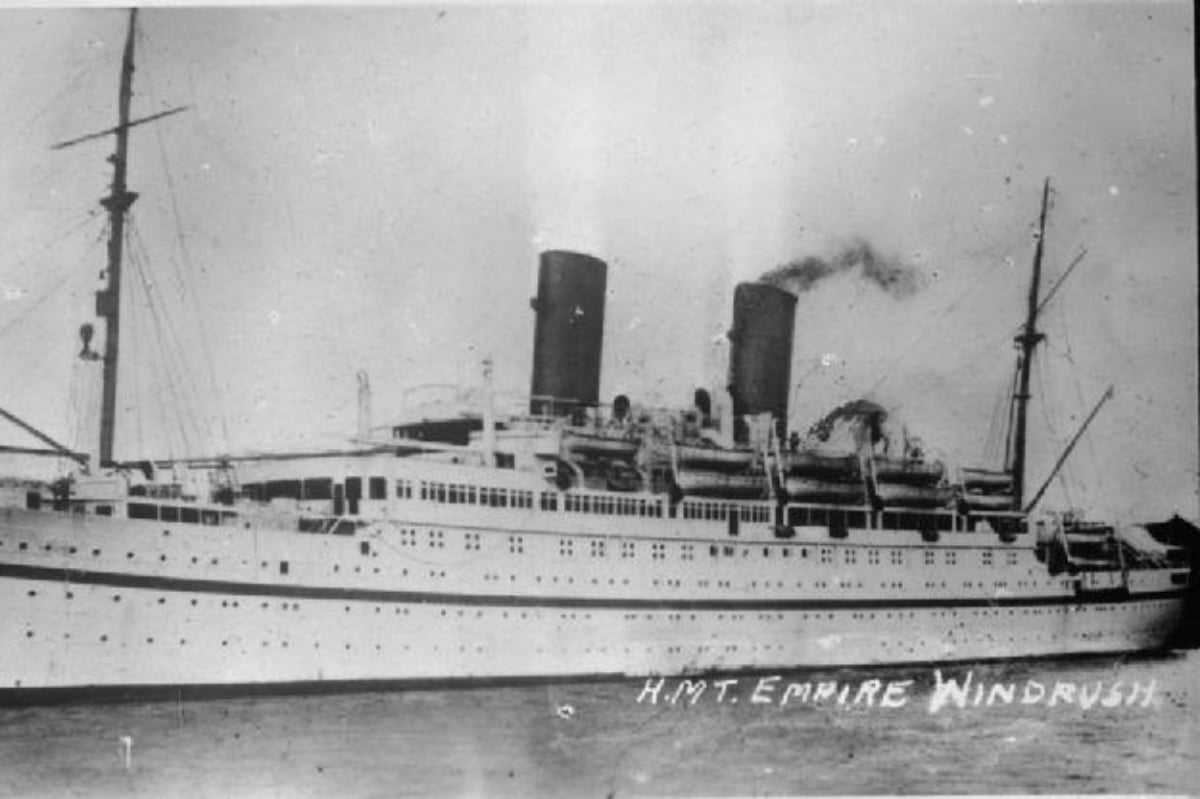

After the Second World War ended, there was a desperate scramble to rebuild the devastated UK economy. With the country suffering from a shortage of labour, the government relaxed immigration controls as part of the British Nationality Act of 1948, enticing peoples from across the Commonwealth to a better life in the metropole.

The capitalists wasted no time in seizing upon this situation, using it to their advantage.

On the one hand, this influx provided the bosses with a steady supply of super-exploitable labour. On the other hand, as is the case today, migrants were regularly scapegoated by the ruling class as being to blame for all of society’s ills.

This served a dual purpose. By fomenting racial divisions, the ruling class attempted to convince white workers that they stood to benefit from discrimination against their black counterparts. This, in turn, helped to create a race to the bottom in terms of wages and conditions across the whole of the working class, boosting the bosses’ profits.

Ridiculously, the colour bar was being enforced in Bristol at a time when the bus company faced labour shortages. But so strong was the vitriol against the Caribbean community in the local and national press that some bosses asserted that it was ‘unsuitable’ for blacks and whites to be expected to work together.

Racist caricatures were used in a campaign of fear and bigotry by the bosses – an echo of the xenophobic tropes used to justify the brutality of the British Empire.

Bristol was no exception to this, with a local Caribbean population of thousands subject to the sharp end of repression and harassment

Unable to feel safe on the streets for fear of Teddy Boy gangs; unable to rent in nicer parts of town; unable to access basic services; and denied the right to work by many employers: life was insufferable, and the prospects for the youth were dire.

Grassroots campaign

But these attacks were not to be taken lying down. To combat this, four young West Indian men – Roy Hackett, Owen Henry, Audley Evans, and Prince Brown – formed an action group called the West Indian Development Council (WIDC). They would soon meet Paul Stephenson, who became the spokesperson of the group.

To prove that the Bristol Omnibus Company was enacting the colour bar, the WIDC set up a job interview for a young black man, Guy Bailey, which was predictably cancelled as soon as the bosses found out that he was of West Indian descent.

This injustice was used as a launchpad for a grassroots boycott campaign, which was officially announced at a press conference on 29 April 1963.

Support spread far and wide in the community, with university students joining a protest on 1 May, International Workers’ Day, which marched to the bus depot and the local TGWU (Transport and General Workers’ Union) office.

Campaigners also linked up with the labour movement to fight their cause. Local MP Tony Benn put pressure on the national Labour Party to oppose the colour bar, and the Bristol Trades Council publicly offered its support.

The bus company became a lightning rod for criticism and anger against racism in Britain. On one side, the boycott struck a chord with thousands of workers subject to the same discriminatory practices across the country. On the other, it increasingly struck fear into the hearts of unscrupulous employers.

Under pressure, on 28 August 1963, Patey climbed down and agreed to change the bus company’s policy. Within weeks, black and Asian workers were being employed on Bristol’s buses.

Trade unions

This victory was no thanks to the TGWU. The trade union tops, reflecting the racism of the ruling class, shamefully spewed out the same divisive lies as the bosses.

Union officials stated, for example, that the employment of ‘coloured’ crews would undermine wages for existing staff, and would lead to white bus workers resigning en masse.

Scandalously, whilst speaking out against apartheid in South Africa in public, the leaders of the TGWU worked hand-in-glove with the bosses to enforce these racist measures back home.

The official position of the union’s Passenger Group was to oppose the employment of non-white workers as conductors or drivers. And the local TGWU branch were accused of colluding with bus company management to implement the colour bar.

TGWU bureaucrats even went as far as finding a local black union member and coaxing him into signing a statement against the WIDC. Hypocritically, this statement argued that the boycott had caused “harm” to the city’s black and Asian population.

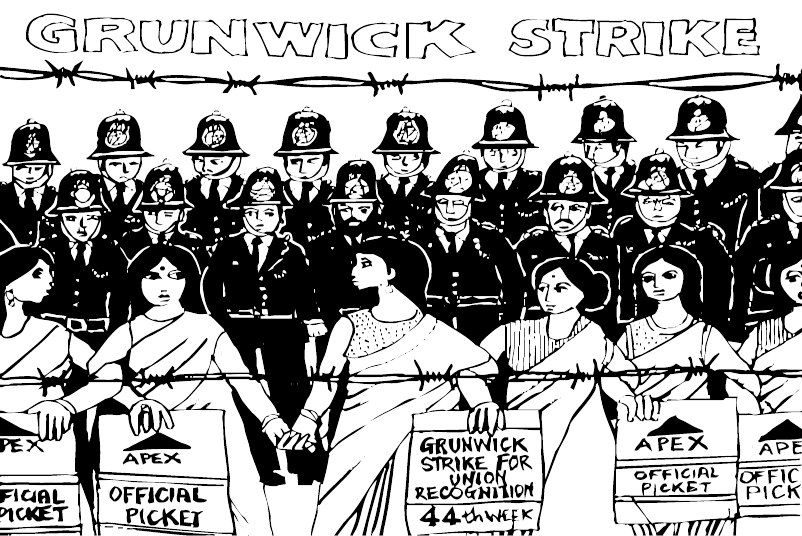

But rather than discouraging activists, this strengthened their resolve. Similarly to the Grunwick strike years later, hampered by union officials, working-class campaigners resorted to their own initiative to push the struggle forward.

Racism today

By winning over the rest of the labour movement, and turning the working-class community against the bosses’ divide and rule tactics, the WIDC showed the way forward in the fight against oppression.

The campaign’s success paved the way for later anti-discrimination laws, such as the Race Relations Acts of 1965 and 1968, introduced by Harold Wilson’s Labour government.

But legislation alone could never end racism in the workplace, which continues to this day.

According to a TUC report released last year, for example, 21% of BAME workers have been bullied or harassed at work. And more than 120,000 workers from such backgrounds have quit their jobs because of racism.

Black and Asian workers may have equality on paper, meanwhile, but they are still more likely to be employed in casualised jobs and outsourced sectors, having to fight for secure contracts.

Similarly, though the Race Relations Acts made it illegal to discriminate in housing and employment, these protections remain mere formalities.

Young people in BAME communities continue to be criminalised from childhood and harassed by the heavy hand of the state. And urban tower blocks serve as holding pens for the poor, disproportionately filled with ethnic minorities.

At the same time, migrant workers routinely face the threat of deportation. And as the Windrush scandal showed, even those who have lived in Britain for generations are effectively relegated to being second-class citizens by the Tories and their ‘hostile environment’.

Fight for revolution

60 years on from the Bristol Bus Boycott and the gains that it won, it is clear that it is not enough to settle for these formal rights.

In order to end discrimination once and for all, and bring about real, lasting change, we must challenge the divide-and-rule agenda of the bosses, pointing out that it is only them that benefit from divisions in the working class.

By organising militant action across the working-class community, the WIDC was able to overcome the prejudices fomented by the capitalists, which unfortunately filtered down into the TGWU through its right-wing leaders.

This highlights what is needed to fight bigotry and oppression today. To combat racism in the workplace, we need organisation and militancy against the bosses.

Unity is our strength. United class struggle is the best way to cast aside the racism of the ruling class.

Above all, workers from all backgrounds need to stand shoulder to shoulder to smash the system that breeds xenophobia and racism: capitalism.

As Malcolm X put it, you cannot have capitalism without racism. So join us in the fight for revolution – for a future free from all forms of oppression and exploitation.