Today, 4 September, marks 50 years since Salvador Allende’s Popular Unity government assumed power in Chile. This year the celebrations will take place in a country shaken by the largest insurrectionary revolts since the return to democracy, which began last October. The main demand behind these massive protests was to wipe out the whole legacy of Pinochet’s regime.

Radical reforms

Allende’s election was a historic milestone. For the first time ever, a socialist President came to power through the ballot box. Allende was elected at the head of a Popular Unity coalition that included the Communist and the Socialist parties. Included in the Popular Unity government’s manifesto were a series of radical reforms in favour of the oppressed masses.

The programme contained, among other measures: “the transformation of the state so workers could exercise power”; national planning at the centre of a mixed economic model; nationalisation of the copper mines and other important natural resources – which were in the hands of foreign capital and big monopolies; nationalisation of the financial system, monopolies, and strategic industries; and a monopoly on foreign trade.

Crucially, the manifesto planned to accelerate and deepen agrarian reform, with expropriated lands to be cooperatively organised. It also proposed wide-ranging reforms such as the extension of social security and medical care; and education reform.

Internationally the Popular Unity government proposed to stand in solidarity with the Cuban Revolution, and for the construction of socialism in the Latin American continent.

Imperialism and capitalism

Some of these reforms were conquered in the first three years of government. In particular, the mines were nationalised; state control of foreign trade was implemented; agrarian reform was intensified; and there were material improvements in the living conditions of working people. Above all, the working masses were raised to their feet.

Some of these reforms were conquered in the first three years of government. In particular, the mines were nationalised; state control of foreign trade was implemented; agrarian reform was intensified; and there were material improvements in the living conditions of working people. Above all, the working masses were raised to their feet.

This programme, although reformist, was too far-reaching to be compatible with the interests of US imperialism and the local capitalists. As Lenin explained, the old ruling class never relinquishes power without a struggle.

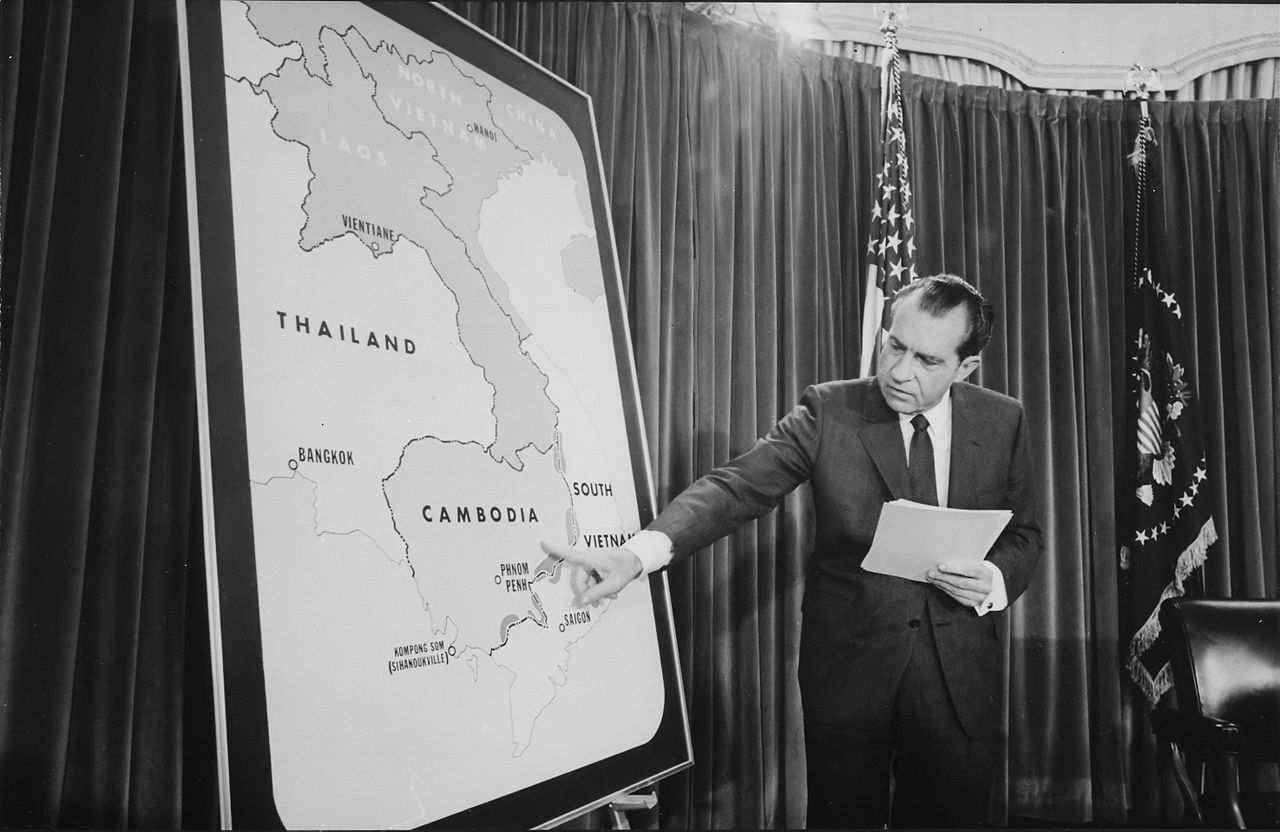

With the Vietnam War raging and an anti-war mood in the United States, however, there were limited possibilities for direct US military intervention. As such, the Nixon administration, in alliance with the national oligarchs, did everything in their power to internally destabilise the country in preparation for a coup.

Systematic sabotage

Taking advantage of a relative parliamentary majority, the right-wing parties imposed a legislative blockade. The Popular Unity government mistakenly attempted to compromise with the Christian Democrats, tying their hands when it came to taking measures to give power to the workers and undermine the capitalist state apparatus. Meanwhile, the CIA funded a campaign of shameless, reactionary propaganda.

Taking advantage of a relative parliamentary majority, the right-wing parties imposed a legislative blockade. The Popular Unity government mistakenly attempted to compromise with the Christian Democrats, tying their hands when it came to taking measures to give power to the workers and undermine the capitalist state apparatus. Meanwhile, the CIA funded a campaign of shameless, reactionary propaganda.

In the economic field, while US mining companies imposed embargoes on Chilean assets abroad, national monopolies carried out sabotage through a boycott on production, capital flight, and withdrawal of consumer goods. This resulted in severe shortages.

All these vile plots were systematically defeated by the masses. In some areas, elements of dual power appeared, mostly on the initiative of workers. Supply and price control councils were established, alongside housewives’ committees, peasants’ committees, and committees in defence of industrial production. These coalesced into ‘Regional Industrial Belts’.

These popular organisations desperately appealed for state support: for legal recognition; for arms to defend the revolution; for a referendum to dissolve parliament; and for the expropriation of the saboteurs. Tragically, they only received kind words from the government.

State and revolution

Despite all the attempts to turn the population against the government, the parliamentary elections in March 1973 saw an increase in the Popular Unity vote.

Despite all the attempts to turn the population against the government, the parliamentary elections in March 1973 saw an increase in the Popular Unity vote.

If the government had rested on the tremendous strength of the working masses, they could have crushed Chilean capitalism and smashed the old state. In its place, they could have formed a new workers’ state, based on arming the workers and generalising the elements of workers’ power that had emerged.

Fatally Allende tried right up until the end to negotiate with the parliamentary representatives of the Chilean ruling class, the Christian Democrats. But whilst negotiations with the representatives of capital went on inside parliament, the capitalists themselves were preparing a coup.

Having failed to frustrate the revolution through parliamentary means, or exhaust it by economic strangulation, the imperialists and the bourgeoisie turned to the reactionary generals.

Coup d’etat

On the morning of 11 September 1973, the coup was launched. British-manufactured jets bombed the presidential palace to ashes, taking Allende’s life, and inaugurating one of the darkest periods in Latin American history.

On the morning of 11 September 1973, the coup was launched. British-manufactured jets bombed the presidential palace to ashes, taking Allende’s life, and inaugurating one of the darkest periods in Latin American history.

The revolutionary workers – unarmed – were unable to put up resistance. For the next 17 years, the military junta headed by Pinochet unleashed savage terror against its opponents, and implemented the most extreme neoliberal counter-reforms.

The lives of thousands of workers and young activists were the price of the failure of the Popular Unity to smash the capitalist state and to carry through the socialist revolution.

As the workers of Chile and the world face a new epoch of revolution, it is important we learn the dearly bought lessons of the earlier Chilean Revolution of 1970-73.