The British establishment normally grabs every chance to mark the anniversary of just about every military event involving British forces known to have taken place in the last hundred years, if not longer. Parades are staged; services of remembrance or thanksgiving held; plaques unveiled and so on – all attended by the great and the good. All with the dismal aim of showing how great Great Britain is.

One such anniversary, however, will yet again pass largely unnoticed – that of the invasion of Suez, the so-called “forgotten war”.

Sixty years ago, on 5th November 1956, British and French troops landed in Egypt in support of Israeli forces in an action which would be deemed by observers as a military success but a political disaster. The Suez Crisis, as it became known, would become a symbol of the death of the British Empire and the end of “Perfidious Albion” as a world-class power. From this point on, certainly in the Arab world, the serious players – the ones who really mattered – would be the competing giants of the USSR and the USA.

Spheres of influence

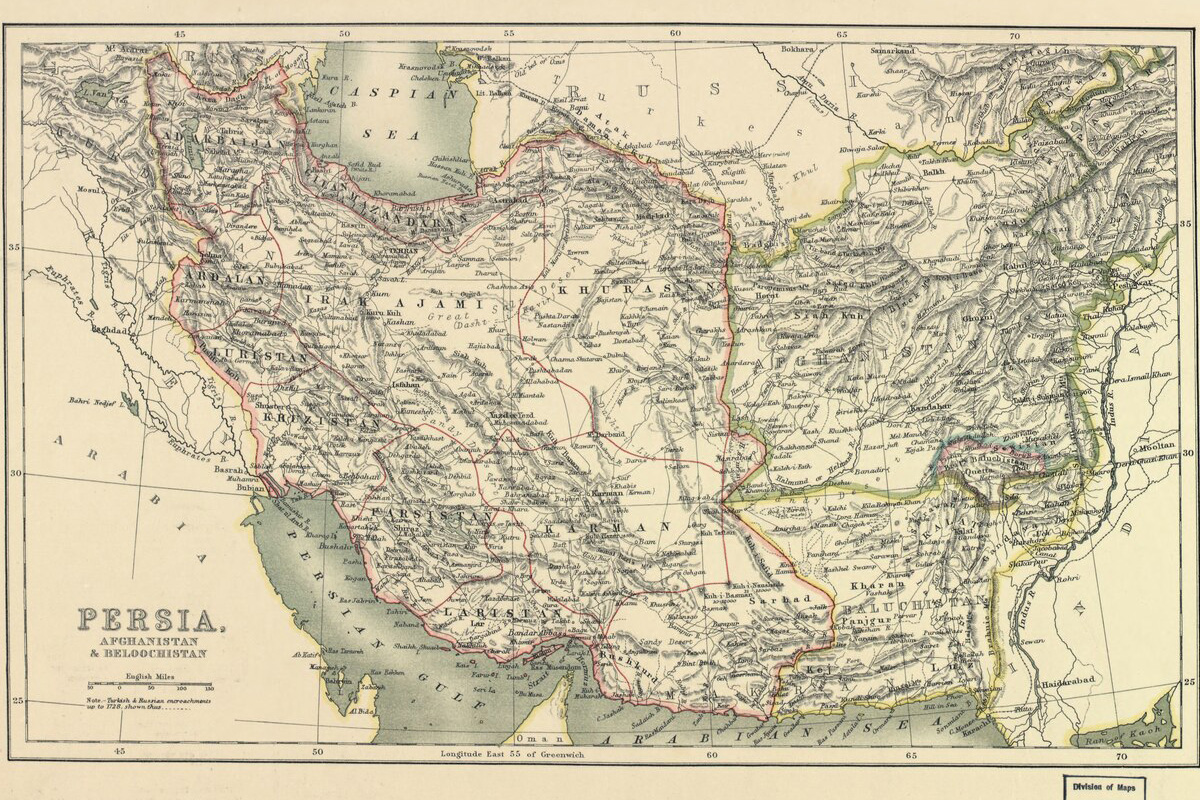

The Suez crisis arose from the fallout from the nationalisation of the Suez Canal by the Egyptian government. The canal had opened back in 1869 as a man-made link between the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean. The building of it had been financed by the two main imperialist interests in the region: the British and French governments. They correctly saw the canal as a strategic weapon in maintaining their dominant positions – on the one hand, by controlling trade; and on the other by providing speedy access to their military forces, both to the region itself and the Indian sub-continent which lay beyond.

The Egyptians had a stake in the ownership of the canal but soon got into debt, a problem conveniently solved by the British government buying up the Egyptian shares in the operating company. After the British invasion of 1888, the running of the canal was firmly under British control, although French investors maintained a majority shareholding. The Treaty of Constantinople confirmed British “protection” and that the canal would be open to all shipping.

Of course, such an agreement only applied if it was in the interests of the British and their allies. During the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-05, the Russians suddenly found their access being denied. A decade later, all those governments who were on the opposite side to Britain during World War One were to be denied use of the canal. When the German and Ottoman Empire forces attempted to take the canal in 1915, over 100,000 British troops were sent to occupy Egypt for the rest of the war and beyond.

Britannia in decline

Although Britain seemed to be in the driving seat during the inter-war years, two factors were starting to undermine its lofty position.

Firstly, the growing importance of oil was starting to attract new players to the game of Arab politics, including far away America. Secondly, the Arab masses who had been under the yoke of various imperialists for many decades – trapped under the rule of an assortment of rotten local kings, princes and governors – had begun to express left-nationalist sentiments. The idea of Pan-Arabism took hold.

The First Great Arab Revolt in the 1930s had been put down by the British occupation forces with great brutality. The British had also started to use the growing demands for a Jewish state in Palestine as a balancing device in the region, playing one against another. The Second World War cut across all this.

In the post-war period, however, where the struggle against colonialism in general – and British and French colonialism in particular – would start to assume a new and greater importance, the question of British and French interests in the Arab world was always going to come to a head. For the masses, the situation was clear: colonial rule had given them nothing and indeed their situation was, if anything, only getting worse.

Nasser and the Free Officers

In 1951, the formerly tame government of Egypt cancelled the 1936 agreement by which Britain was allowed to have a huge military base at Suez. Britain simply ignored – as all imperialists do – the wishes of the country they were in reality occupying and maintained their position by rule of force. Anti-British protests grew in cities like Cairo and the British responded with the might of the gun.

For a layer of the Egyptian establishment this was a step too far. The Egyptian monarchy had proved themselves incapable of standing up to the British in any meaningful way. On 23 July 1952, the crony regime of King Farouk was removed in a coup by members of a left-nationalist “Free Officers Movement”. One of the movement’s leaders was Gamal Abdul Nasser, who would become president of a new Egyptian republic.

At first, Britain believed they could negotiate with Nasser and maintain their position in the region. In 1953, Britain agreed to quit the Sudan and carry out a “phased withdrawal” of forces from Suez. In return the Egyptians would let the colonial powers keep the Nile Valley region. The Suez Canal would remain under British and French ownership until at least 1968. Meanwhile, to avoid having all their eggs in one basket, the British begun building closer links with Iraq and Jordan, both seen as potential opponents of Egypt in the struggle to become the de facto leadership of the Arab world. The Baghdad pact of 1955 seemed to confirm this in the eyes of Nasser – a pact involving Iran, Iraq, Turkey, Pakistan and, of course, Great Britain.

Meanwhile the Americans were starting to sniff around, noting that over half of all traffic going through the canal was carrying oil. Wary of the likely growing presence of the USSR in the region, the USA had attempted already to establish a Middle East Defense Organisation, aimed at combating Russian encroachment. Washington saw Egypt as being key to this and believed that Nasser would be a useful ally. Indeed it was widely believed that the CIA might have played some role in supporting the coup against King Farouk, who was seen as Britain’s man. Indeed, this period would mark a straining of the “special relationship” between America and Britain, which would only be repaired once Britain had accepted that it was now very much the junior partner in any such arrangement.

The Cold War

To describe even briefly all the intrigues, deals and double deals, plots and so on, which took place during the period after 1952 on the part of the great powers and their potential allies (and enemies) would fill a space far beyond that allowed for this article. Suffice to say that the illusions being held in London and Washington about who they could trust would prove to have far less basis in fact than they had hoped.

Nasser begun to see the advantage of playing America off against Russia – and against the old colonial masters of Britain and France – as a means of strengthening his position in the Arab world. Nasser had made clear that he wanted to buy arms from the Americans, but when they were not forthcoming, mainly due to concerns over Egypt’s anti-Israel stance, an arms deal was struck in 1955 with Czechoslovakia, a Warsaw Pact country, with the support of Russia, who now saw a way of getting its foot further in the door. Cold war politics had arrived.

If Britain was nervous about all this, so was France. The rise of opposition to French colonial rule in Algeria was shaking the Paris establishment and they needed someone to blame. Nasser fitted the bill, and soon demands were being made to “do something about him”. The French tactic was therefore to increase arms supplies and support to the fledgling state of Israel.

In 1956, Nasser moved to ally himself closer with Jordan and pressure was put to get King Hussein to remove Sir John Bagot Glubb (better known as Glubb Pasha) from his position as British commander of the Arab Legion. Britain took this dismissal as a clear message. The British Prime Minister, Anthony Eden, was furious and would become obsessed with getting rid of Nasser. A political and media campaign begun to paint Nasser as a dictator like Hitler and Mussolini. Interestingly, the Labour leadership under Hugh Gaitskell would initially join in this “bi-partisan foreign policy” approach, echoing a tendency we had seen before – and would see again up to the present day with Blairite support for the bombing of Syria.

Imperialist intervention

The Americans could see where the build-up of arms for both Egypt and Israel was leading and decided to intervene. However, all talks of a settlement proved barren as spring turned to summer in 1956. Nasser was being offered nothing of substance and in July decided to act. On July 26th, without warning, Egypt nationalised the Suez Canal, removing the British overlords. The canal was immediately closed to Israeli ships along the straits of Iran. Egypt also blockaded the Gulf of Agaba.

Eden and the British government were furious – how dare these foreigners act without telling us in advance! A special session of parliament condemned the nationalisation, with Labour again backing the Tories, as did the British press. Plans were immediately put in place to act.

The French moved first, agreeing on July 29th to take military action with Israel. It was confirmed to them on August 7th that Israel would indeed be ready to invade – they saw Egypt as being increasingly hostile to them given the treatment of the Palestinians. A London conference was called in August, with representatives of Britain, France and the US in attendance, to discuss the crisis but with no clear solution. A further conference was again held in London later that month with representatives invited from all countries who used the canal. Egypt did not attend but were backed at the event by India and Russia. The conference demanded, by majority vote, international (i.e. imperialist) control of the canal.

Negotiations with Egypt over this proposal got nowhere, needless to say. The Americans then proposed an “association” of canal users that would draw up guidelines of operation. The US hoped that this plan would enable them to be seen as separate from Britain and France who were widely seen as the main imperialist aggressors by the Arab world. In fact, both countries went along with the US plan, but largely to buy time before taking military action. Indeed, Britain begun to assume that Washington would not object should any such action take place.

On September 1st, France and Israel began organising the details of an invasion of Egypt. France would use Israeli airstrips to launch bombing raids should British ones, based in Cyprus, not be available. In October, Britain was let in on the plan and at a secret conference outside Paris, all three countries – Britain, France and Israel – agreed on the tactic they would play. Israel would invade first, targeting Sinai, with France and Britain following on in as “peace-keepers” to “separate” the Israeli and Egyptian forces and in doing so re-occupy the canal and remove Nasser from power. Britain would maintain its hold in the Middle East and both France and Britain could use the invasion to keep pressure on their African colonies. A huge military operation was started to prepare for the invasion, set for late October. Meanwhile the Americans were monitoring all this through the CIA. So too were the Russians.

Invasion

On October 29th, the Israeli invasion begun, with the French giving logistical support to Israeli forces. Both French and Israeli airplanes engaged in bombing sorties. On October 30th, France and Britain carried out the first part of their deal by sending ultimatums to both Egypt and Israel. Nasser responded by sinking ships in the canal, thereby blocking it to all traffic.

On November 5th, British troops landed at the El Gamil airfield. The invasion had begun. The next day British forces landed at Port Said. From a military point of view, the conduct of the British invasion was fairly successful with considerable advances for relatively little loss of British lives (the same could not be said of Egyptian casualties), but this would not prove to be the problem for Eden and the British government.

At home, huge opposition to the invasion was growing. The Labour leadership was coming under huge pressure to break with Eden, and this they reluctantly did. A House of Commons debate nearly erupted into fistfights it was said. Opinion polls were showing growing opposition to the invasion and a massive anti-war protest was held in London on 4th November, the day before British troops landed in Egypt. Many saw comparisons with the Soviet invasion of Hungary a few weeks earlier. Even some Tories started to express concerns, forgetting their nationalist bravado of July and August. Eden wanted to take direct control of the BBC to direct propaganda in support of the invasion but was resisted on this. Again, this was a problem that would be taken very seriously in later military actions, from the Falklands through to Kuwait, Iraq, Serbia and Afghanistan.

The Americans too were worried. Russia was starting to use the imperialist adventure to curry support in the Arab world, at America’s expense. Something had to be done, and quickly. The UN had met on November 2nd to pass a US motion calling for peace. Britain, France, Israel and a number of other countries allied to them either voted against or abstained. The US continued to put pressure on France and Britain to call off the invasion and withdraw, noting that Russia had made threats to use nuclear bombs to back Nasser. More worryingly was the fact that Israel was considering the invasion to be a great victory and was now looking to build on this at the Arab world’s expense. A complete redrawing of the political map was being considered by them.

America could wait no longer. Financial pressure was put on Britain to stop this adventure. Oil sanctions by the US seemed likely. An oil embargo was indeed started by Saudi Arabia under direction from America. Other countries were set to join in. Neither France nor Britain had the financial resources, still depleted from the Second World War, to withstand this.

Second-rate powers

Britain had no choice. A ceasefire was announced on 6th November by Britain without even telling the French. All advances were halted. British and French troops were told to withdraw by December 22nd to be replaced by UN representative forces. Some Tories were furious, seeing the military advances and demanding that the job be finished. Israel refused to have any dealings with the UN, but finally left the Sinai in March 1957, having destroyed all they could. The question of the ownership of the Suez Canal was now made clear by the US and UN – it was Egyptian, not British or French. As the Daily Herald put it at the time, “Britain and France have been cut down to size, and reduced to their status of second-rate Powers.”

America had chosen to back Nasser, not Eden. In coming years, the so-called “Eisenhower doctrine” of the US would be put in place: backing Arab nationalism and promising financial aid, but also military force should Russia cross the line. Israel was out in the cold, a situation that would continue until it had become very clear that the doctrine was not working and Russia had come out ahead in the struggle for influence in the Arab world. Nasser’s position was also strengthened, with Nasserism – as it was called – becoming a dominant concept in Egypt and beyond.

One clear loser was Eden himself. With the invasion having been wound up in shame, clear opposition at home, and evidence that he had misled parliament, he had no choice but to resign as PM on January 9th 1957. Macmillan took over and begun the job of winding up the rest of the British Empire, preferring to concentrate on economic advance at home – “you’ve never had it so good”. Within a few short months the truth had become clear: in the post-war world, France and Britain were out, America and Russia in.

Cutting the knot of imperialism

Writing at the time, Ted Grant said:

“Nothing has been solved. The Middle East remains a powder-keg of discontent and antagonisms. The attempt to squeeze out Russian and American influence has failed. The Russian influence in the area is increased. Throughout the world the Anglo-French Imperialists have incurred the odium of being “aggressors”…The relations between British capitalism and her dominant partner America will have to be sorted out, with Britain accepting the role of very secondary partner.

“In the Middle East the ferment of the Arab masses will be further increased by these events. The yearning for unity of all the Arab States will receive a powerful impetus. The rottenness of the feudal-capitalist rulers has been revealed. The way is being prepared for a new Nationalist upsurge, which will further complicate the problem for the Imperialist Powers.”

“For the British workers, the problems of Suez and the Middle East can only be solved in the interests of the Arab and British peoples by a struggle for power on a Socialist programme, which would include mutual aid and assistance to the Colonial Peoples. Reliance on the Dis-United Nations can merely bind the masses hand and foot with the knots of the discords of the Great Powers. The only way to solve the problem of this modern Gordian knot is to cut through the tangle, with an uncompromising class anti-Imperialist policy. For the working class there can be no other solution.” (Suez—the Crisis of Western Imperialism. 1956)

Ted Grant’s analysis has been more than borne out. The bluster of the colonial relics who had ruled the world had been exposed for all to see. The direct imperialist control of countries like Britain would be replaced with rule by proxy. America would seek to impose itself into the vacuum which now existed using its economic might alongside a large amount of behind-the-scenes dabbling. For the masses, the following years would present little change in their economic circumstances. The only way forward remains the struggle for the overthrow of these rotten and despotic regimes and the establishment of a socialist federation of the Arab world and the Middle East.