A century ago, on 15 October 1923, the Left Opposition was established by a statement by 46 prominent members of the Bolshevik Party.

Led by Leon Trotsky, this opposition strove to defend the genuine traditions of Bolshevism against the Stalinist bureaucracy. Fighting against the stream due to the depressed mood of the masses, the Opposition was eventually defeated within the USSR.

Trotsky went on to found the International Left Opposition, from which the International Marxist Tendency traces its heritage.

At the time, and even up to this day, the legacy of the Left Opposition has been dragged through the mud by Stalinism. But it is time to set the record straight.

What did the Left Opposition really stand for – and against?

New issue of IDOM magazine coming out very soon! In this issue – insight into Soviet Economy and how it was organised, a piece on Soviet theatre and the figure of Konstantin Stanislavsky, and an in-depth analysis of catastrophe of German Revolution in 1923. Pre-order now! pic.twitter.com/TpgRKkuDYF

— Wellred Books Britain (@WellredBritain) October 4, 2023

Rise of the bureaucracy

The Russian Revolution of October 1917, under the leadership of the Bolsheviks, was the greatest event in history. For the first time, apart from the episodic Paris Commune, the working class drove out the capitalists and landlords and took power into its own hands.

Inspired by October, the hopes of millions internationally became directly linked to the revolution, which was followed by a series of revolutionary events from 1917 to 1921. Revolution put power into the hands of the German workers in November 1918, but the Social Democratic leaders handed it back to the capitalists.

The defeat of the German Revolution and the further isolation of the Russian Revolution had a dramatic effect. The dire backwardness and isolation of the revolution increased the power of the old bureaucracy, which began to creep back into positions within the state and even the Bolshevik Party.

The atrocious conditions of famine and scarcity had weakened the tiny working class and caused the organs of workers’ democracy – the soviets – to fall into disuse.

“Scratch the workers’ state at any point and beneath the fine veneer of socialism is the same old Tsarist state machine,” explained Lenin.

As the former Tsarist bureaucrats climbed back into the driving seat, a shift was taking place in the masses and a ‘regroupment’ was taking place in the state and party. This was the material basis for the rise of Stalinism.

Both Marx and Lenin understood that the only way to combat bureaucracy was the participation of the masses in the running of government, industry, and society generally. But the backwardness and objective difficulties facing the working class – who were working 10, 11 and 12 hours a day and more – rendered this impossible.

Alarmed by this rise of the bureaucracy, Lenin launched his last struggle to fight against this bureaucratic menace. This struggle took place at the end of 1922 and in the first two months of 1923, and was marked by Lenin’s personal break with Stalin.

Lenin had suffered a stroke that left him partially paralysed. On the next day, he began to dictate his testament. Lenin was shocked when he found out about the treatment of the leading Georgian Bolsheviks by Stalin.

As a consequence, Lenin prepared a ‘bombshell’ – declaring that Stalin must be removed as general secretary of the party. But before this could be carried out, Lenin was laid low by another stroke.

To prevent Trotsky from assuming the leadership of the party, Stalin, with Zinoviev and Kamenev, the ‘old Bolsheviks’, created a triumvirate. They dug up all the old disagreements, especially between Lenin and Trotsky, and threw them into the face of the members. This was done for entirely cynical reasons, and was nothing to do with defending Leninism.

Founding of the Left Opposition

The first serious clash between Trotsky and this triumvirate came in October 1923. The economic situation had deteriorated and widespread strikes had broken out in many areas.

This heightened discontent in the country also reflected itself inside the Bolshevik Party. But the response of the central committee (CC) under the control of the triumvirate was to stamp down hard on opposition currents, outside and inside the party.

Confronted with this serious situation, Trotsky wrote to the central committee on 8 October, protesting at the emergence of an “unhealthy regime within the party”. He lambasted the wide-scale system of appointments and the undermining of party democracy at all levels.

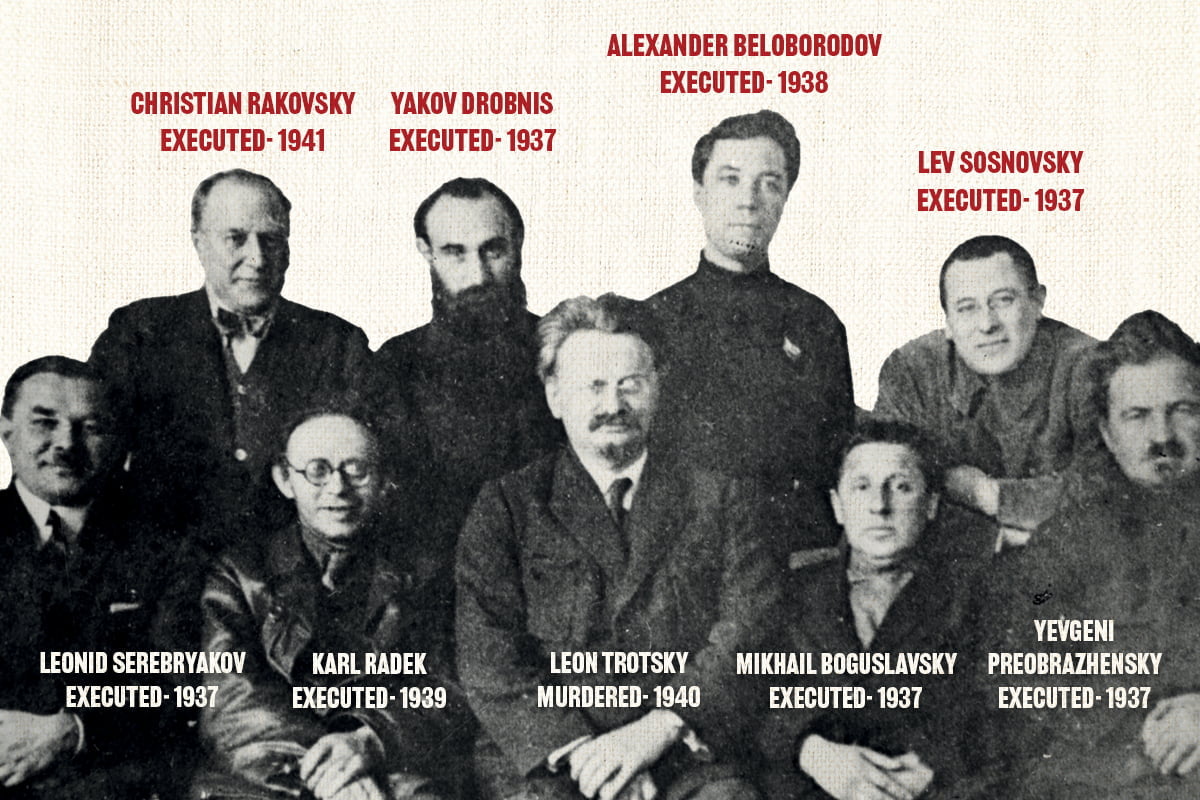

On 15 October 1923, 46 prominent party members, many of them the most high-ranking Bolsheviks during the Civil War, issued a statement to the Politburo known as ‘The Platform of the 46’ in support of Trotsky’s criticisms.

The Opposition demanded the restoration of workers’ democracy in order to fight against the bureaucratic degeneration of the party and the state apparatus.

The ‘Platform’ also called for the legalisation of factions within the party, which had been temporarily banned by the Tenth Congress. This ban was never intended to be used to repress genuinely democratic discussion within the party. Lenin had acted as a check on this while he was healthy.

The Platform’s immediate demand was for a special conference of the central committee and leaders of the Opposition to settle their differences. But the reply of the Politburo accused Trotsky of “instigating a struggle against the central committee”.

While none of Trotsky’s arguments were answered, they accused him of wanting to become “dictator of economic and military affairs”.

Neither Trotsky’s letters nor the ‘Platform of the 46’ were published or shown to the party. Instead, the Politburo opened up a one-sided campaign against the Left Opposition. Trotsky replied with a series of articles, which were published as a pamphlet entitled ‘The New Course’.

In ‘The New Course’, Trotsky warns of the dangers of degeneration of the ‘Old Guard’.

“In its prolonged development,” he wrote, “bureaucratisation threatens to detach the leaders from the masses, to bring them to concentrate their attention solely upon questions of administration, of appointments and transfers, of narrowing their horizon, of weakening their revolutionary spirit…Such processes develop slowly and almost imperceptibly, but reveal themselves abruptly.”

Despite all the attacks and slanders by the triumvirate, the views of the Opposition gained support. Significantly, there was a majority in the units of the Red Army, as well as in the Young Communist League, who voted in favour of the Opposition. In Moscow, a majority also came out for the Opposition. But the apparatus, under the control of Stalin, ensured that the votes at the Thirteenth conference would be rigged.

Socialism in one country?

Lenin’s death on 21 January 1924 served to free all restraints from the triumvirate. Stalin attacked Trotsky personally at the Thirteenth Party conference in May. Lenin’s Testament was suppressed and regarded by the Politburo as a subversive document. Stalin increasingly became the open mouthpiece of the bureaucratic reaction.

The bureaucrats wanted peace and quiet to get on with running their affairs, not world revolution. Lenin’s death constituted a turning point for them. It was no accident that at this time, Stalin came forward with the notorious theory of ‘socialism in one country’.

The internationalists under Trotsky’s leadership fought back against this anti-Marxist theory. The whole history of Bolshevism had opposed the idea of a ‘national socialism’, especially in backward Russia. Lenin explained many times that without world revolution, an isolated revolution would be doomed to fail.

This theory of ‘socialism in one country’ represented the outlook of the bureaucrats and careerists who wanted to put a brake on the revolution. Its adoption changed the Communist International from an instrument of international revolution into a border-guard for the defence of the Moscow apparatchiks.

Trotsky predicted that the adoption of the pernicious theory would inevitably lead to the nationalist and reformist degeneration of the Communist International. This prediction proved astonishingly correct, and the International was formally disbanded by Stalin in 1943 as a gesture to the Allies.

1924 witnessed another turning point in the struggle of the Opposition. It was at this time that Trotsky published ‘Lessons of October’ – a brief but brilliant analysis of the Russian Revolution and its lessons.

Trotsky pointed to two internal crises in the party in 1917: one in April, when Lenin fought against the Old Bolsheviks to rearm the Party for the coming revolution; and again in October, when Zinoviev and Kamenev wavered and came out against the insurrection.

At each crucial stage, Lenin had met the opposition of the ‘Old Bolsheviks’. Trotsky highlighted the importance of farsighted leadership, and explained that its lack was one of the key factors which had led to the failure of the German revolution in 1923.

Of course, the triumvirate was aghast. They immediately went on the offensive with a series of articles attacking Trotsky. Isolated quotes, ripped out of context, were splashed across the newspapers to distort Trotsky’s past and present.

The Russian Central Committee, despite two votes against, condemned Trotsky for his attempts to ‘revise Leninism with Trotskyism’. They resolved to remove him from the Chairman of the Revolutionary Military Council, and the government, and resolved to explain to “all the ranks of the party the anti-Bolshevik character of Trotskyism – from 1903 to ‘Lessons of October’”.

Splits in the triumvirate

But by 1925, serious splits were emerging once more, even within the triumvirate. The New Economic Policy (NEP), which had initially been instituted as a temporary measure to stimulate the agricultural economy, was having grave consequences. The grip of the kulaks and Nepmen speculators had grown to alarming proportions.

These pressures were increasingly being reflected in the party leadership, where Bukharin and Stalin favoured the continuation of the policy of further concessions to the market. Bukharin famously advocated: “To the peasants, we say – ‘enrich yourselves!’”

This sharp shift to the right provoked swift reaction from the proletariat of Leningrad. This in turn introduced splits at the top, pushing Zinoviev, whose base was in Leningrad, into opposition. Kamenev, Zinoviev’s ally, joined him.

Stalin, of course, acted quickly to eliminate the opposition in Moscow and Leningrad, and again rigged the congress, this time against Zinoviev and Kamenev.

The shift to the right was also reflected in the International, which took an opportunist turn. Explosive events were maturing in the East, with the beginning of the Chinese Revolution. By 1925, the Communists were the biggest working-class party in China, and victory lay within reach of the Chinese workers and peasants.

But there was one problem: Stalin and Bukharin both argued that the Chinese Revolution was not socialist, but bourgeois anti-imperialist in nature. The Communists were ordered by Moscow to dissolve themselves into the Guomindang, a nationalist party led by Chiang Kai-Shek.

The Left Opposition described this position as a Menshevik one, similar to the popular front in Russia in 1917. Trotsky called for the Chinese Communists to wage a struggle against imperialism, linked to a revolution led by the working class, as in Russia, with the support of the peasants. Stalin and Bukharin, of course, attacked this ‘Trotskyist’ position, and even gave Chiang an honorary position in the Comintern!

Stalin’s policy led to a complete disaster. In March 1926, Chiang Kai-shek staged a counter-revolutionary coup in Guangzhou. The news of this was suppressed by Stalin, for fear it would be used against him by the Opposition. Within 12 months, Chiang had drowned the revolution in blood, carrying out a brutal massacre of thousands of communists and workers in April 1927.

Stalin and Bukharin’s Menshevik policies had guaranteed the bloody defeat of the Chinese Revolution. While the predictions of the Opposition gained it support, it also further demoralised the working class. Trotsky explained:

“Our comrades expressed optimism because our analysis was so clear that everyone would see it and we would be sure to win the party. I answered that the strangulation of the Chinese revolution is a thousand times more important for the masses than our predictions…

“The military victory of Chiang Kai-shek will inevitably provoke a depression and this is not conducive to the growth of a revolutionary faction.” (Our emphasis)

The United Opposition

These events produced a political realignment. The triumvirate split and Zinoviev and Kamenev were forced into an alliance with Trotsky, creating a new United Opposition. Clearly, there was distrust between the Oppositionists. But a greater enemy forced them together.

The United Opposition formally came into being in April 1926, and was very impressive in the leading personnel that it attracted to its ranks. Such was the talent attracted to the Opposition that Kamenev told Trotsky: “It will be enough for you and Zinoviev to appear on the same platform for the party to recognise its real central committee.”

But this was over-optimistic. The Opposition was swimming against the stream, given the defeats and setbacks over the past period. It would take truly great events to bring the masses again to their feet.

The Opposition had to organise in a clandestine manner in order to establish the network of a national organisation. The initial membership was between 4,000 and 8,000, based upon recruits from the older generation and the youth.

But their faction was soon uncovered by an agent provocateur. In revenge, Zinoviev was removed from the Politburo, and Lashevich, the deputy commissar for war, was expelled from the CC.

The CC made preparations to ban the Opposition. Every attempt to get a hearing was blocked by the apparatus, with hooligan gangs organised to prevent Oppositionists from speaking.

Though Zinoviev and Kamenev took fright at the growing repression, Trotsky was determined to fight for his ideas and the restoration of party democracy, no matter what the consequences.

The Opposition decided to use the opportunity of the forthcoming Fifteenth Congress to put forward its platform. But Stalin simply postponed the party congress until the end of 1927, which gave him sufficient time to ruthlessly purge the party.

Trotsky sober-mindedly wrote about this period just before his death:

“The Left Opposition could not take power…A struggle for power, led by the Left Opposition, by a revolutionary Marxist organisation, can be conceived only in the conditions of a revolutionary uprising…The conditions of the Soviet reaction were infinitely more difficult for the Bolsheviks than Tsarist conditions had been.”

Platform of the Opposition

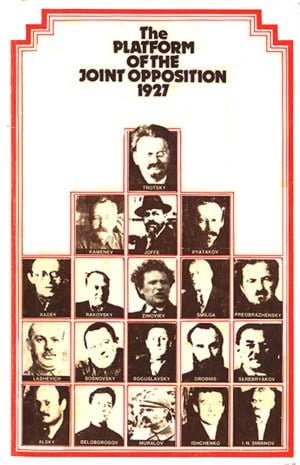

In September 1927, the United Opposition issued a programmatic document entitled ‘The Platform of the Opposition: The Party Crisis and How to Overcome It’.

The Platform exposed the opportunist line of the leadership. It demanded a change of course, away from concessions to the kulaks and for a planned industrialisation of the country. It demanded a timely increase in living standards, the restoration of workers’ democracy, and the readmission of all those expelled for opposition views from the International.

The Platform was submitted to the Politburo by thirteen members of the central committee for the Fifteenth Congress. However, the CC forbade the distribution of the Opposition document. The Opposition had no alternative but to circulate it secretly.

An old communist and printer, Fishelev, managed to print several thousand copies of the document. As a result, he was arrested and sent to a labour camp near the Arctic Circle for ‘misappropriating paper and equipment’. Others who circulated the Platform were threatened with expulsion, imprisonment, and exile.

At the CC meeting on 23 October, Stalin again raised the demand for the expulsion of Zinoviev and Trotsky. When Trotsky spoke, he was interrupted by continuous frenzied heckling, where books and glasses were thrown at him.

If they had any chance of being heard, the Opposition had to go deeper into the ranks. They went from factory to factory, wherever they had supporters to hold meetings.

The Opposition decided to take part in the demonstration celebrating the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution under their own slogans. Their comrades carried banners with slogans such as: ‘Strike against the kulak, the Nepmen, and the bureaucrat!’ and “Against opportunism, against a split – For the unity of Lenin’s party!’ But though there was sympathy among the masses, there was no mood for a fight.

Within a week, a special meeting of the CC took place to expel Trotsky and Zinoviev for “inciting counter-revolutionary demonstrations”. Rakovsky, Kamenev, Audeev, Smilga, Yevdokimov were also expelled, while six other Oppositionists were expelled from the control commission.

Hundreds more were then purged, all of which prevented the Opposition speaking at the Congress.

Towards an International Left Opposition

The Fifteenth Congress formally made membership of the Opposition incompatible with party membership. This broke the will of Zinoviev and Kamenev, who collapsed and begged for readmission to the party.

In January 1928, Trotsky was charged with counter-revolutionary activities and forcibly taken into exile in Kazakhstan. Stalin thought that by deporting Trotsky he could isolate him from his supporters in the USSR.

But Stalin had made a big mistake. The capitulation of Zinoviev and Kamenev freed Trotsky’s hands. It allowed him to clearly differentiate himself from them.

Of course, the Left Opposition was hit hard by a wave of capitulations from the leaders of the old 1923 Opposition: Pyatakov, Antonov-Ovseenko, and Krestinsky. Others followed suit, such as Preobrazhensky and Radek. But despite all the persecutions and repressions, the basic cadre of Trotsky’s Left Opposition remained intact. This was a colossal achievement.

Trotsky was soon banished to Turkey, where he immediately began work on establishing an international opposition. Given his history, despite all the difficulties and persecution, he alone was suited in leading this enormous task.

Within a few years, in 1930, the first international conference of Bolshevik-Leninists took place. This was to officially give birth to the International Left Opposition.

As Trotsky explained in 1931:

“Only a frightful earthquake can bring such devastation in the field of material culture as the administrative conduct of the epigones [Stalinists] has brought about in the field of the principles, ideas, and methods of Marxism.

“It is the task of the Opposition to re-establish the thread of historical continuity in Marxist theory and policies.”

This red thread of genuine Marxism continues today with the International Marxist Tendency. We alone are defending the revolutionary heritage and legacy of Lenin, Trotsky, and the Left Opposition.

We call on communist workers and youth to join us and continue their struggle – the struggle for world socialist revolution.