“I got to the theatre at about five, and had difficulty in getting in, though I had a special ticket as a correspondent. There were queues outside all the doors. The Moscow Soviet was there, the executive committee, representatives of the trade unions and factory committees, etc.

“The huge theatre and platform were crammed, people standing in the aisles and even packed close together in the wings of the stage. Kamenev opened the meeting by a solemn announcement of the founding of the Third International in the Kremlin. There was a roar of applause from the audience, which rose and sang the ‘Internationale’ in a way that I have never heard sung since the all-Russian assembly when the news came of the strikes in Germany during the Brest negotiations.”

These are the words written by a British eyewitness, the journalist Arthur Ransome, to the celebration of the founding of the Communist (Third) International, held at the Bolshoi Theatre in March 1919.

Moscow was still in the last grip of winter. “Moscow lacks fuel,” wrote Jacques Sadoul, a French consultative delegate. “The congress delegates shiver. Moscow has been on meager rations the last two years. International comrades do not always eat their fill…”

51 delegates from more than two dozen countries – many of who were smuggled across the imperialist blockade and barbed wire – attended the founding congress of the new international in Moscow. That this small number made it was remarkable in itself, as the gathering was deemed “illegal” by the blockaders. As a result, some delegates were arrested and did not make it.

First and Second Internationals

The Third International was born out of the great betrayal of the First World War and the electrifying events of the Russian Revolution of October 1917.

The Third International was born out of the great betrayal of the First World War and the electrifying events of the Russian Revolution of October 1917.

As is clear from the name, there were two earlier internationals, a first and second, in whose history we can trace the evolution and continuity of Marxism.

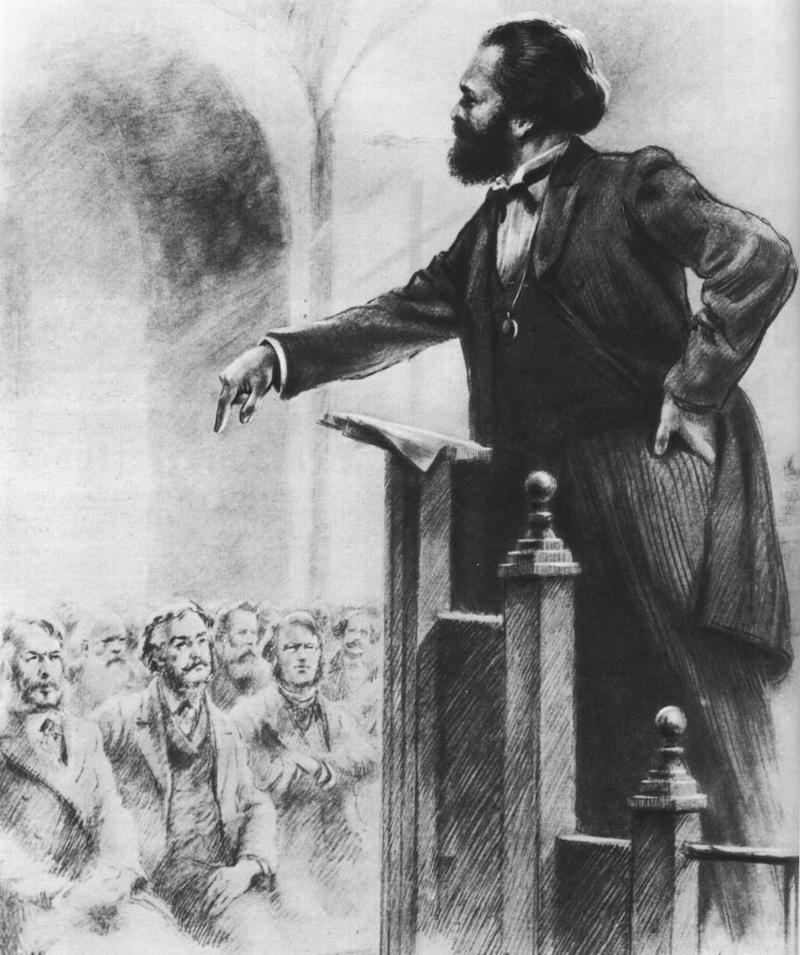

The First International (known as the International Workingmen’s Association) was established with the direct participation of Marx and Engels in 1864. This body, while relatively small, laid the foundations of the working class struggle for international socialism. However, it was a victim of the reaction that spread across Europe after the defeat of the Paris Commune in 1871. It was eventually dissolved in 1876.

Just over a decade later, Engels participated in the founding of the Second International in 1889. Unlike its precursor, this was composed of mass workers’ parties comprising of millions. Nevertheless, the International was constructed during a general advance of capitalism, in a period where there were no revolutionary battles.

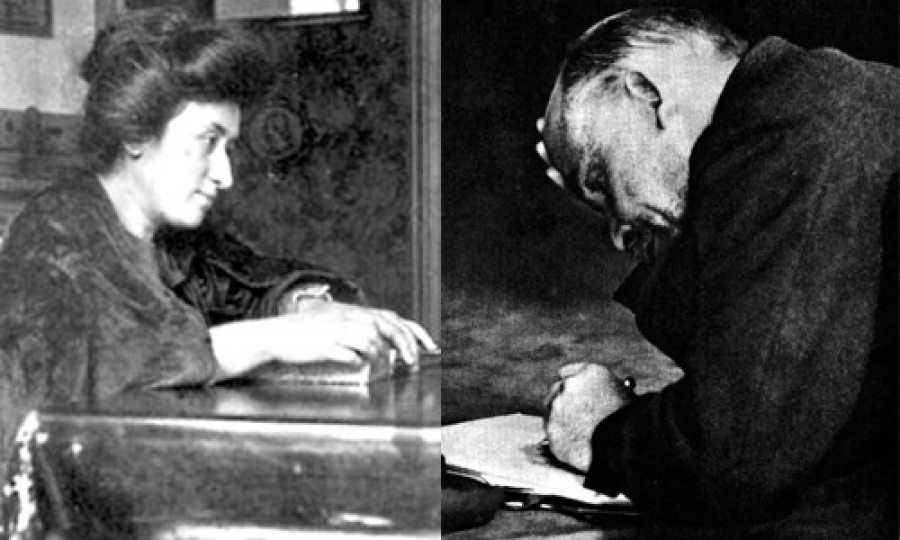

This led to an opportunist degeneration within its leadupership. Over time, the revolutionary struggle was pushed into the background in favour of the struggle for reforms. But as Rosa Luxemburg argued, the question of reform and revolution should have been intrinsically linked together and not divided into separate struggles.

Eventually, despite the fine speeches, this opportunism led to the betrayal of August 1914, when the socialist leaders abandoned internationalism and sided with their own ruling classes in the ensuing world war.

Zimmerwald

Arising from this debacle, the internationalists, who remained firm to the ideas of world revolution, were reduced to a tiny handful. Amongst those loyal to the cause of international socialism were Lenin and Trotsky in Russia, Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht in Germany, John MacLean in Scotland, James Connolly in Ireland, James Larkin and Eugene Debbs in America, and others.

Arising from this debacle, the internationalists, who remained firm to the ideas of world revolution, were reduced to a tiny handful. Amongst those loyal to the cause of international socialism were Lenin and Trotsky in Russia, Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht in Germany, John MacLean in Scotland, James Connolly in Ireland, James Larkin and Eugene Debbs in America, and others.

When their first gathering took place in 1915 at Zimmerwald, Lenin joked that the internationalists of the world could fit into two stage coaches. This summed up their terrible isolation.

The tiny group at Zimmerwald adopted a manifesto denouncing the imperialist war, rejecting “national defence” in such a conflict, and called on the workers to unite in a struggle for peace, emancipation and socialism.

This was followed by a further meeting at Kienthal in 1916. Lenin and the Bolsheviks were on the extreme left wing at both Zimmerwald and Kienthal. They called for the abandonment of the old Second International (as opposed to its reform) and the establishment of a Third International. It was this left current that was to form the nucleus of the new international in March 1919.

October Revolution

The decisive turning point and the real impetus for the new international was the victory of the Russian Revolution in October 1917. Here, for the first time in history (apart from the brief episode of the Paris Commune), the working class took power.

The decisive turning point and the real impetus for the new international was the victory of the Russian Revolution in October 1917. Here, for the first time in history (apart from the brief episode of the Paris Commune), the working class took power.

The Bolshevik Revolution was never regarded as a purely Russian event. Such an idea was unthinkable, especially in such a backward country. Isolated, the revolution would be doomed. The Bolsheviks understood that the socialist revolution could only succeed on a world scale.

Following the victory of the Russian Revolution, the bourgeoisie internationally immediately conspired to crush the young workers’ state through the methods of blockade and armed force. However, the revolutionary events in Russia helped to provoke revolutionary upheavals throughout Europe. Most notably of these was the German Revolution in November 1918, which put an end to the First World War.

Soviet Republics were declared in Bavaria and Hungary in early 1919. Out of this revolutionary period, new revolutionary parties – Communist Parties – began to form in Germany, Austria, Hungary, Netherlands and Poland. In many other countries, pro-Bolshevik tendencies began to crystallise in the old mass organisations.

By the end of 1918, the Bolsheviks in Russia had concluded that the time had come to launch a new revolutionary international, free from the opportunism and betrayals of the Second International. Revolutionary, reformist, and centrist tendencies took shape throughout the international labour movement. Millions of workers worldwide began to look to the Bolshevik Revolution as a way out of the carnage of the First World War and the crisis of capitalism.

To take advantage of the situation, Lenin proposed to organise an international conference and invite only those:

“1) who resolutely stand up for a break with the social-patriots (i.e., the people who, directly or indirectly, supported the bourgeois governments during the imperialist war of 1914-1918);

“2) who are for a socialist revolution now and for the dictatorship of the proletariat;

“3) who are in principle for ‘Soviet power’” as a type of government “higher and closer to socialism.”

Lenin suggested that the conference might be convened on 1st February 1919 “in Berlin (openly) or in Holland (secretly)”, but this was being optimistic. As it turned out it took place a month later in Moscow.

Leadership

The Communist Party of Germany had been formed at the very end of December and was the strongest and most authoritative of the communist groups outside of Russia. It had recently been made illegal, arising out of the “Spartacist Week”. Its two main leaders, Luxemburg and Leibknecht, had been murdered.

The Communist Party of Germany had been formed at the very end of December and was the strongest and most authoritative of the communist groups outside of Russia. It had recently been made illegal, arising out of the “Spartacist Week”. Its two main leaders, Luxemburg and Leibknecht, had been murdered.

Its formation was decisive for the launching of the Third International, even though the party’s leadership had grave reservations concerning the timing of the new international’s foundation. These were overcome through discussion, and the decision was taken without a single delegate being opposed.

The task of the founding congress of the Third International was to cut across all the confusion and redefine the principles of international socialism, which had been betrayed by the old leaders. It had been these leaders who had saved capitalism.

In Germany, Noske, Ebert and Scheidemann conspired with the elements of the monarchist regime to destroy the revolution and eliminate the workers’ and soldiers’ councils that in effect held power. They then embarked, hand in glove with the Junkers, on the road of counter-revolution. This betrayal was to lead eventually to the bloody dictatorship of Hitler.

The Third International was created in response to this betrayal. The revolutionary wave that was sweeping Europe cried out for a real revolutionary leadership.

Foundations

The congress immediately got down to business. Its main discussions concentrated on the present stage of capitalism, the character of reformism, and the forms that the proletarian revolution would take.

The congress immediately got down to business. Its main discussions concentrated on the present stage of capitalism, the character of reformism, and the forms that the proletarian revolution would take.

There was a certain mood present that a spontaneous movement of the working class would be sufficient in itself to bring down capitalism. As Trotsky explained:

“The First Congress convened after the war at a time when communism was just being born as a European movement and when there was a certain justification for reckoning and hoping that the semi-spontaneous onset of the working class might overthrow the bourgeoisie before the latter succeeded in finding a new orientation and new postwar points of support. Such moods and expectations were by and large justified by the objective situation at the time…

“In any case it is unquestionable that in the era of the First Congress (1919) many of us reckoned – some more, others less – that the spontaneous onset of the workers and in part of the peasant masses would overthrow the bourgeoisie in the near future.” (First Five Years of the Communist International, vol.2)

The Third International did not see itself as a competitor to the Second International, which still maintained an existence, but as a successor. It was built on the theoretical foundations and work of the First and Second Internationals.

“The epoch-making significance of the Third, Communist International lies in its having begun to give effect to Marx’s cardinal slogan, the slogan which sums up the centuries-old development of socialism and the working class movement, the slogan which is expressed in the concept of the dictatorship of the proletariat,” explained Lenin.

“This pre-vision and this theory – the pre-vision and theory of a genius – are becoming a reality… A new era in world history has begun.”

Lenin and Trotsky

An International is first and foremost a programme, ideas and traditions, and only secondly an organisation to carry these into practice. It was these that needed to be clarified and defended.

An International is first and foremost a programme, ideas and traditions, and only secondly an organisation to carry these into practice. It was these that needed to be clarified and defended.

The International adopted the title of “Communist” to differentiate itself from the social democrats, who had betrayed socialism. It was a reversion to the Communist traditions of Marx and Engels and the Communist Manifesto – a clean banner.

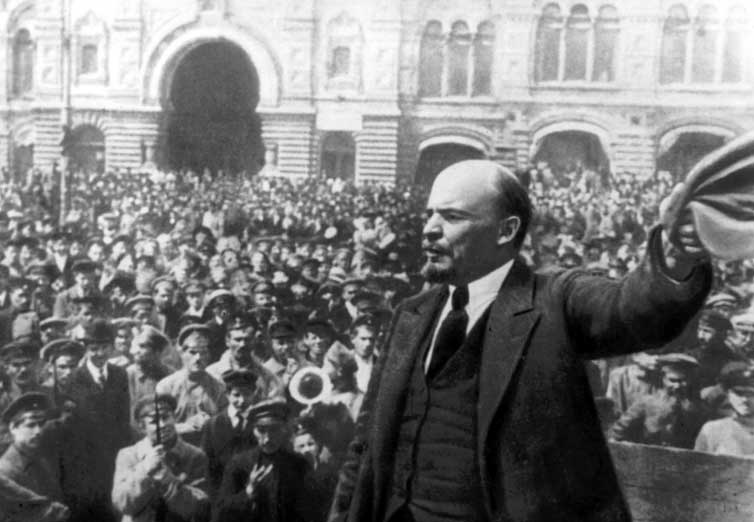

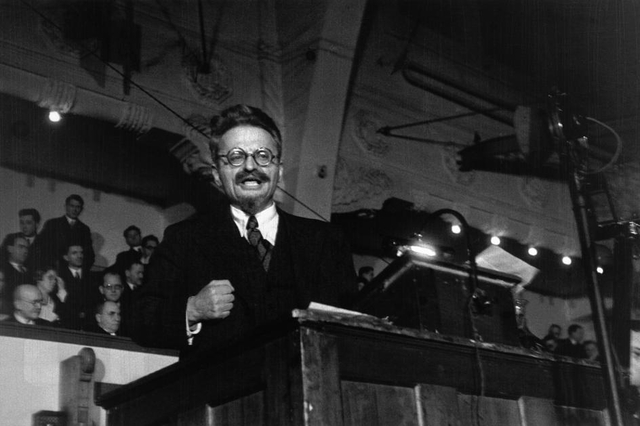

As you would expect, given the prestige of the October Russian Revolution, the influence of the Russian leaders was immense. Lenin and Trotsky gave the main political reports, which dealt with the fundamental questions.

The report on the Theses on the Bourgeois Democracy and the Dictatorship of the Proletariat was made by Lenin. Trotsky both authored and introduced the Manifesto of the Communist International to the Proletariat of the Entire World.

Lenin explained that concepts of “democracy” was meaningless without explaining its class content. Even the most democratic state is only a cover for the suppression of the working class by a handful of capitalists. The task of socialists was to replace the capitalist state with a state that served the interests of the workers. This, explained Lenin, should be modelled on the principles of the Paris Commune, where the workers held power briefly.

The Commune was not a parliamentary institution but a self-governing, mass workers’ organisation where there was no division between legislative and executive power.

“The capitalists have always used the term ‘freedom’ to mean freedom for the rich to get richer and for the workers to starve to death,” explained Lenin. “In capitalist usage, freedom of the press means freedom of the rich to bribe the press, freedom to use their wealth to shape and fabricate so-called public opinion.”

He went on to explain we want real freedom. “The Paris Commune took the first epoch-making step along this path. The Soviet system has taken the second.”

Soviet power

The Soviets were not an invention of the Bolsheviks but the self-organisation of the working class. Soviet is simply the Russian word for a workers’ council. It was the basis of workers’ self-rule.

The Soviets were not an invention of the Bolsheviks but the self-organisation of the working class. Soviet is simply the Russian word for a workers’ council. It was the basis of workers’ self-rule.

“Destruction of state power is the aim set by all socialists, including Marx above all,” Lenin stated. “Genuine democracy, i.e., liberty and equality, is unrealisable unless this aim is achieved. But its practical achievement is possible only through Soviet, or proletarian, democracy, for by enlisting the mass organisations of the working people in constant and unfailing participation in the administration of the state, it immediately begins to prepare the complete withering away of the state.”

In contrast to the dictatorship of capital, the Bolsheviks put forward Marx’s phrase of the dictatorship of the proletariat. This ‘dictatorship’ was the democratic rule of the working people – nothing more, nothing less.

Of course the term ‘dictatorship’ today has a totally different meaning than when used by Marx or Lenin. With the rise of the totalitarian dictatorships of Stalin and Hitler, the meaning changed. Today, rather than use the term ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’, we would use the term ‘workers’ democracy’.

So it was that the Bolshevik Party inscribed on its programme in 1919 the famous four conditions for Soviet power:

- Free and democratic elections with the right of recall of all officials.

- No official to receive a higher salary than that of a skilled worker.

- No standing army but an armed people.

- Gradually, all the tasks of running the state should be performed by everyone in turn. “When everyone is a bureaucrat, no-one can be a bureaucrat.”

World revolution

Trotsky addressed the congress by outlining a Manifesto of World Revolution. “Our task is to generalise the revolutionary experience of the working class,” he said, “to purge the movement of the corroding admixture of opportunism and social-patriotism, to unify the efforts of all genuine revolutionary parties of the world proletariat and thereby facilitate and hasten the victory of the Communist revolution throughout the world.”

Trotsky addressed the congress by outlining a Manifesto of World Revolution. “Our task is to generalise the revolutionary experience of the working class,” he said, “to purge the movement of the corroding admixture of opportunism and social-patriotism, to unify the efforts of all genuine revolutionary parties of the world proletariat and thereby facilitate and hasten the victory of the Communist revolution throughout the world.”

In a passage that is extremely relevant today, Trotsky said:

“Statisticians and pedants of the theory that contradictions were being blunted, had for decades fished out from all corners of the globe real or mythical facts testifying to the rising well-being of various groups and categories of the working class. The theory of mass impoverishment was regarded as buried, amid contemptuous jeers from the eunuchs of bourgeois professordom and mandarins of socialist opportunism. At the present time this impoverishment, no longer only of a social but also of a physiological and biological kind, rises before us in all its shocking reality.”

Lenin summed up the confidence of the First Congress of the Third International in his closing remarks:

“No matter how the bourgeoisie of the whole world rage…all this will no longer help. It will only serve to enlighten the masses, help rid them of the old bourgeois-democratic prejudices and steel them in struggle. The victory of the proletarian revolution on a world scale is assured. The founding of an international Soviet republic is on the way.”

A world to win

The First Congress was followed each year by a World Congress which led to the building up of a theoretical arsenal of revolutionary Marxism: against ultra-leftism; the need for a united front, the need for mass Communist parties; and a whole host of other important questions.

The First Congress was followed each year by a World Congress which led to the building up of a theoretical arsenal of revolutionary Marxism: against ultra-leftism; the need for a united front, the need for mass Communist parties; and a whole host of other important questions.

The Third International was a vast school or parliament where ideas were thrashed out and a common position agreed.

The first four congresses were a milestone. After that, with the defeat of the German Revolution in 1923 and the death of Lenin in 1924, the Russian Revolution was left isolated. In conditions of economic backwardness, this led to the rise of Stalinism.

The adoption of the theory of ‘Socialism in One Country’ resulted in a reformist and nationalist degeneration of the Third International. From being the vanguard of the world revolution, the International was, under Stalin and his cronies, purged of its best elements and turned into a tool of Stalinist foreign policy.

This led to one disaster after another: in China, Germany, Spain, and elsewhere. Eventually in 1943, in a gesture to the Allies, Stalin formally dissolved the Communist International.

Today, the crisis of capitalism is deepening and revolutionary events are on the order of the day. The great days of the Third International of 1919-1923 will live again.

A new generation needs to learn the lessons from this valuable experience. We need to prepare ourselves for the events ahead. As with the Third International, we enshrine on our banner: workers of the world, unite!