With recent figures indicating a small growth in the economy, a number of commentators are once again talking about the “green shoots of recovery”. But for the majority of people, this does not feel like a recovery. Unemployment is still high, and those jobs that are being created are low-waged and insecure. Matthew Wood discusses the state of the UK economy and its real effects on living standards.

A recent article in The Guardian by Paul Mason, BBC Newsnight’s outgoing economics editor asks what the Left should do in the face of economic recovery.

“What recovery?” we might ask. Well, on August 23rd, the Office for National Statistics revised GDP figures up for the second quarter of 2013. Growth was at 0.7% in quarter two, following on from a 0.3% rise in quarter one. August has also seen news of another fall in unemployment. “Only” two and a half million British people – 7.8% of the workforce – are now officially unemployed. Perhaps then capitalism’s crisis is over, the ‘green shoots’ of recovery are sprouting through and the works of Karl Marx can be placed back on the shelf.

Such a view though is very superficial; if we probe even a little deeper we quickly find the real nature of capitalist recovery. As Marxists we understand that history does not move in a straight line, and under capitalism an economic crash can give way to a temporary recovery in some form. Historically, capitalism has crashed and recovered many times over its lifetime. However, whereas in earlier periods capitalism would bounce back from crisis quickly and with only a short hangover, now recovery is slow and unspectacular.

A huge expansion in investment in capital goods – e.g. plant and machinery – or an expansion into new territories and markets through colonialism – i.e. imperialism – also meant that when capitalism was in its expansionary phase, economic recovery meant the return of employment. The long postwar upswing from 1945 until the 1970s was the last great example of this, and it was in this period that the working class, particularly in advanced capitalist countries, won political victories and concessions from the capitalist state on welfare, wages, housing, health, education and pensions.

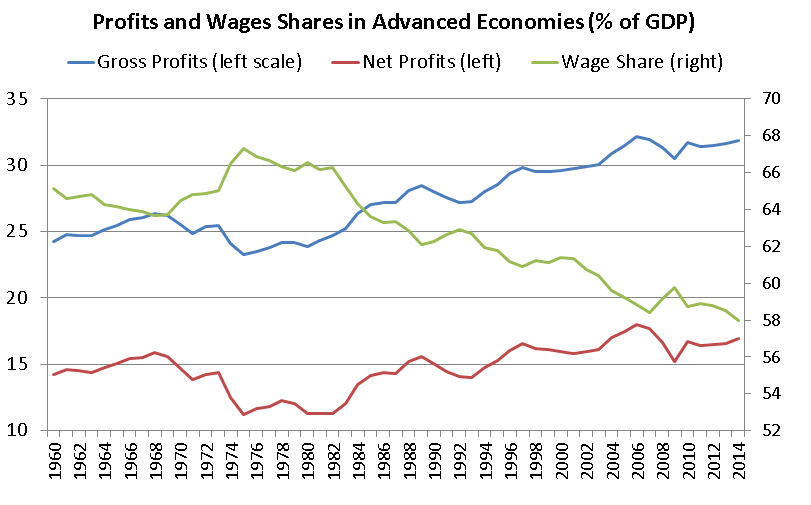

A recent article in a Financial Times blog published some interesting data, including the graph below, which shows the long-term decline in the share of GDP (economic output) going to labour – in the form of wages – for the advanced capitalist countries that came after this upswing.

This decline in relative wages – i.e. the value of annual wages compared to the total value produced in the advanced capitalist countries – was a necessary part of the recovery that followed the slump of the 1970s. Attacks on the working class were essential to the capitalist recovery of the 1980s, demonstrated most starkly by the policies of Thatcher and Reagan.

The “recovery” of 2013 is taking on a similar form. A recent article in The Economist reported on falling living standards for British workers; the sub-heading put it concisely: “Growth is back. But for many Britons it does not feel like it”.

This article points out the rapid post-recession decline in wages, and also mentions that the majority of new jobs are precarious and low waged. This is the new “hourglass economy”, with a small capitalist class, and its hangers on of salaried managers, at the top, and a working class at the bottom, with a large proportion on zero-hour or otherwise short-term contracts, with low wages, working in unskilled jobs. The Economist states that, “research by the Trades Union Congress shows that four in five net jobs created up to December 2012 were in low-wage sectors”.

Even if the current upswing is to be sustained over a prolonged period, it is not, as many commentators are pointing out, going to feel like an upswing. Mason is aware of the ‘patchy’ nature of the upswing and notes that, “it is true that GDP per head is stagnating. It is also true that if you measure GDP against the retail price index, instead of the government-preferred CPI, it is flat. It’s also true that growth is patchy regionally – not just between regions but even within small towns…”

After reporting on the recovery, the second point of Mason’s article is to encourage the Left – in particular the Labour Party – to “acknowledge the recovery” and reframe the debate on the question of what to do now austerity has, apparently, been proven to have worked. We might have expected this tactic from the Labour leadership, who have shamefully acquiesced to the need for government cuts, but it is not the honest or correct path for the Party to take, especially if it wants to win the next election. A Labour Party that fails to energise its working class base and offer a socialist alternative to the austerity programme of the Tories and the Lib-Dems runs the risk of a repeat of the 2010 general election, with working class voters abstaining in the face of any real choice.

A recovery that does nothing to improve the lot of ordinary people is a recovery only in abstract terms. To think that a recovery on this small scale could then be used by the Labour Party to win concessions for workers, youth, pensioners, etc. misunderstands the nature of capitalism.

As has already been pointed out many times, productive capacity utilisation (which is only running at between 50-75%) and cash reserves of big business (which stand at around $700bn) show that the problem is not there is no wealth in society, but rather that opportunities for profitable investment and production – which is what a capitalist economy operates for – are few and far between. The capitalist class will remain cautious for a long time yet, and without any prospects for a massive expansion into new markets, or of new innovation-led growth, the ruling class will resist any substantial proposals for redressing the imbalance between profits and wages.

If the Labour Party proceeds down the route of pleading with the Tories for “capitalism with a human face” and capitulates to a big business government’s arguments about the necessity of austerity, they can – and are – swiftly be discredited in the capitalist press as irresponsibly toying with a fragile recovery.

If, on the other hand, the Labour Party boldly rejects austerity and develops a mass campaign for the socialist transformation of society, it will not only be portrayed as the enemy of capitalism, but will also re-establish its tradition as the political representative of the working class, who, under this “recovery”, sees no prospect of a meaningful job, a home or a retirement.

Under capitalism, this is the long term perspective. In an article on wages failing to keep up with inflation for 40 straight months now, James Plunkett from the Resolution Foundation, which has just authored a report on living standards in Britain, says “we know that this trend is almost certain to continue through 2014 and into 2015 before there’s a realistic prospect of wages beginning to recover. Even then it is likely to be several years before wages return to levels seen before the recession.”

This is a recovery in name only and will be of little benefit to the average worker. In fact, it may set the scene for even more aggressive anti-worker policies of the Con-Dem government. For the Labour Party to be a proper opposition it must not only be against austerity, but also for the socialist transformation of society.