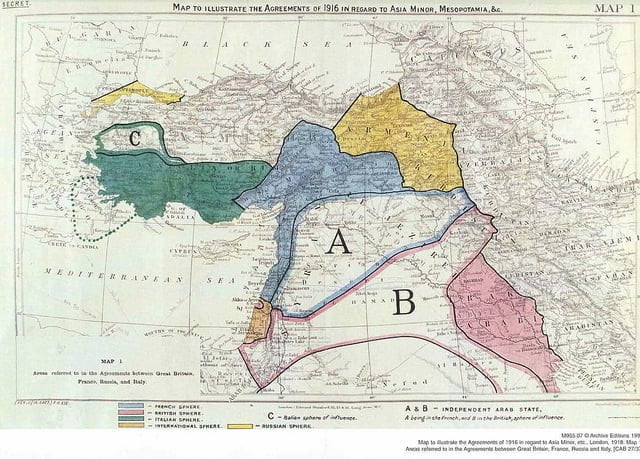

The frontiers of the Arab world today are the product of a secret plan drawn in pencil on a map of the Levant in May 1916 in a deal struck between British and French imperialism at the height of the First World War. Worked out one hundred years ago, the Sykes-Picot agreement is now synonymous with imperial deceit, cynicism and treachery.

The frontiers of the Arab world today are the product of a secret plan drawn in pencil on a map of the Levant in May 1916 in a deal struck between British and French imperialism at the height of the First World War. Worked out one hundred years ago, the Sykes-Picot agreement is now synonymous with imperial deceit, cynicism and treachery.

The authors of this notorious document were Sir Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot, appointed by the British and French governments respectively to decide how carve up the Ottoman Empire after the War. Hovering in the background was the Russian foreign minister Sergei Sazonov, anxious to ensure that Constantinople would be handed over to Russia as part of the deal.

During the War Britain made different offers to different countries. The French, the Arabs and the Jews were all promised things that the British imperialists had no intention of giving them. Arab historian George Antonius called this document the product of “greed allied to suspicion and so leading to stupidity”. It was a messy solution that prepared the way for future disaster.

The Turks had miscalculated badly when they entered the War on the side of Germany and the Central Powers. Now their lands were up for grabs. The only question was: who would grab what? Like rival gangs the bandits of the Entente were already arguing how to split up the goods of the man they planned to murder. But there was a slight problem. Their intended victim was not yet dead.

At the time the war was not going well for the Allies. The Gallipoli adventure launched on the initiative of Winston Churchill ended in disaster. In January 1916, while a ferocious battle was being fought in Verdun, the British had been forced into an ignominious withdrawal. A few months later the British were about to suffer a humiliating defeat in Mesopotamia.

Oil

Even at this early stage the presence of oil was a decisive factor in the calculations of imperialism. What was the right of self-determination when compared to this black gold? before 1914 Britain already controlled large parts of what is today called Iraq, bribing the local sheikhs to obtain influence such as in the case of the Sultan of Kuwait. The importance of this was to secure the Shatt-Al-Arab, the name given to the point where the waters of the Euphrates and Tigris are joined. This was a key port for British Indian trade.

The construction of the Anglo-Persian oil pipeline that ran along the banks of the river made it even more important for Britain to secure the region. Anglo-Persian Oil Company was the company that kept the Royal Navy supplied with oil, a fundamental strategic consideration. Just before the outbreak of war the British government had secured a controlling interest in the company. The vast profits thus obtained rivalled those of the Suez Canal Company. There was money in oil. And there was blood also.

All this was ultimately related to the British control of India. In theory British interests in Mesopotamia were protected by the British forces in India. But in reality the latter were not sufficient. The attention of the Foreign Office in London was drawn to the possibility of provoking an Arab uprising against the Turks.

The Arabs suffered oppression under Turkish rule and many were restive. The politicians in London thought they saw in this an opportunity. They imagined that if the Turks could be driven out of Basra, the Arabs would be inclined to rise against them and support the British in their war against the Ottoman oppressors. But in practice this turned out to be a mirage.

In the words of one British military historian, “British policy was not free from an unpleasing Machiavellianism for while the Arabs were urged to throw off Turkish allegiance, so pledge was given against their ultimate return to the vengeance of their ferocious masters.” (A History of the Great War, p. 339-40) The author adds, as if to excuse himself: “Doubtless, however, our action was regarded as aa fair counter to Turko-German intrigues in India, for which Mesopotamia was regarded as a useful base.”

“March on to Baghdad!”

A British force composed partly of Indian troops was sent into Mesopotamia. The Political Officer of this expedition, Sir Percy Cox, was considered to be a great expert on the region. He argued enthusiastically in favour of marching on Baghdad. There would be little or no opposition, he thought. But he thought wrong.

The military planners had left out of account several factors, one of the most important being the climate: one of the most unforgiving and extreme in the world. The British and Indian forces suffered the torments of heat and thirst, plagued by flies and struck down by diseases. Later they suffered from the cold. The field hospitals were, to say the least, inadequate and an increasing number of soldiers were beginning to fall. Wounded men were spending up to two weeks on boats before reaching any kind of hospital. This was a warning of the horrors yet to come.

Sir John Nixon, the head of the army of Mesopotamia, was unmoved by any of these little local difficulties. It is hard to say whether his conduct was the product of naivety or megalomania. Cromwell once said: “No man goes so far as he who knows not wither he is going.” Overcome by his irrepressible optimism, Nixon only seemed to know one word of command, and that word was “Advance!”

Appetite comes with eating, and the British were getting greedy. At first things appeared to do well. By late September 1915 Nixon’s forward divisional commander, Sir Charles Vere Ferrers Townshend, had already occupied the Mesopotamian province of Basra, including the town of Kut al-Amara. From there, they attempted to move up the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers toward Baghdad.

General Townshend seems to have been a very vain and arrogant man, his ego having been inflated by some military successes against tribal guerrillas in northern India. Like Nixon he was absurdly self-confident. That self-confidence cost many lives. He was reckless, taking absurd risks while neglecting the most elementary precautions. The end result was catastrophe.

The easy victory in Basra filled the British with a fatal sense of complacency. But all too often in war the ability of advancing leaves out of account the desirability of so doing. In the end the Arab population did not turn out to be as friendly to the British as the men in London had hoped. Often the Turkish forces were backed by hordes of Arabs, who also began sabotaging the oil pipelines. For these actions the local population were subjected to a “severe chastisement” by their British saviours.

From a military point of view the occupation of Baghdad did not make any sense. In order to carry out such an operation successfully would have required a very large number of troops and huge amounts of supplies, river transport, field hospitals and artillery. Instead of this, the British force consisted of only 12,000 men who were sent marching through desert country with no roads and inadequate supplies. But Sir John pressed on regardless.

The 6th (Poona) Division advanced upriver, leaving a very thinly stretched supply line of hundreds of miles behind them. Nixon deceived himself and deceived the British government with his bragging tone. He told Chamberlain: “I am confident that I can beat Nur-ud-Din and occupy Baghdad without any addition to my present force.” In London the Cabinet hummed and hawed, wrote memos and then wrote other memos, and finally, swayed by the confident assurances of “the men on the ground”, they decided to send reinforcements to the invading force (Kitchener voted against).

The vast majority of the British Empire forces in this campaign were recruited from India. But the British authorities in India were becoming increasingly alarmed by the deteriorating situation on the turbulent north-western frontier with Afghanistan. They were also beginning to be concerned at the success of the very efficient and tenacious German agents who were increasingly active in Teheran. It was feared that Persia might enter the War on Germany’s side at any moment. The Government of India reluctantly decided to try to scrape together some reinforcements. But it was a case of too little and too late.

What they did not know in London or New Delhi was that this tiny force of 12,000 veterans were about to walk into a trap. In late November at Ctesiphon (or Selman Pak), sixteen miles outside Baghdad, they collided with an army of 20,000 Turks.

The catastrophe of Kut

The battle was fought with great ferocity and casualties were high on both sides. Being outnumbered by the Turks two-to-one, Townshend’s troops were rebuffed with the loss of 4,500 men. The Turks lost about twice that number, but Townshend was in far worse shape than them, having lost 40 percent of his infantry and half his British officers. A ragged and dispirited army began the retreat back to Kut-al-Amara. On the fifth of December Turkish and German troops began to lay siege to that city.

In the beginning the seriousness of their position had not yet penetrated the thick skull of Sir Charles Townshend. In the officers’ mess they dined almost as well as in the exclusive clubs for gentlemen in London. They drank toasts to King and Country in champagne and consumed quantities of excellent whiskey. Nobody saw the terrible end that was staring them in the face.

Convinced that they would soon be relieved, they saw no reason to worry. But heavy winter rains had swollen the Tigris River, making it difficult to manoeuvre troops along its banks. Consequently the anticipated relief force did not appear. Townshend sent whinging, at times hysterical demands for help,

Four times the British attempted four times during the winter to break the Turkish siege, only to be driven back. Townshend made no effort to support the relief efforts by organising a sortie from the besieged city but merely remained passive. The number of casualties suffered by the relieving forces was around 23,000 – almost twice the strength of the entire remaining forces inside Kut.

As the siege dragged on, food became scarce. Sickness began to strike down on the men who were weakened by exhaustion and hunger. The situation was even worse for Indian soldiers who were forbidden by their religion to eat horse meat. Morale sank along with dwindling supplies.

Now desperate, Townshend pleaded with the British government negotiate a grubby deal with the Ottomans. They attempted to buy off the enemy with a huge bribe. A team of officers (including the notorious “Lawrence of Arabia”) was sent secretly offered two million pounds (the equivalent of £122,300,000 in 2016), promising they would not fight the Ottomans again, in exchange for Townshend’s troops. The Turkish leader Enver Pasha contemptuously turned this offer down.

Although reinforcements were not so far from the city, instead of waiting, Townshend suddenly surrendered on 29 April 1916. The general and his 13,000 men were taken prisoner. This was the single largest surrender of troops in British history and it dealt a shattering blow to British prestige. British historian James Morris has described the loss of Kut as “the most abject capitulation in Britain’s military history.”

Townshend and most of the other British commanders involved in the failure to relieve Kut were removed from their command. But they got off lightly compared to the grisly fate of the men under them. C.R.M.F Cruttwell writes

“Townshend [went] into an honourable and almost luxurious interment, the officers into endurable prison camps. The men were herded like animals across the desert, flogged, kicked, raped, tortured and murdered. Though the Germans gave them tokens of humanity and kindness almost wherever they met them, more than two thirds of the British rank and file were dead before the war ended. Halil the Turkish commander had cynically promised that they would be ‘the honoured guests of his government.’ The relieving force had suffered 23,000 casualties. Mainly composed of young barely trained troops, it had nobly endured every kind of avoidable and unavoidable hardship and suffering.” (A History of the Great War, pp. 348-9)

The class divisions in society persist even in prisoner of war camps.

Betrayal of the Arabs

When Turkey entered the War on the side of the Central Powers, London immediately declared Egypt a British “protectorate.” The people of Egypt merely exchanged one imperial master for another. Naturally, their opinion on the matter was never consulted.

During the war, British agents worked tirelessly to whip up an Arab revolt against the Turks. The exploits of one of these T.E. Laurence were made famous in the film Lawrence of Arabia, which presents these activities in a most flattering light. In fact, this was part of a cynical plan to use the Arabs against the Turks, winning over the tribal chiefs and sheikhs by a mixture of vague promises of territorial expansion for the future and very tangible monetary bribes for the present.

The men in London believed they had scored a great success in persuading Emir and Sharif of Mecca Hussein bin Ali to proclaim a rebellion against the Ottoman rule. In fact, this action, which he took with great reluctance, was not the result of British diplomacy, but the fact that he had discovered a German plot to get rid of him. Without this bit of encouragement, his preference would have been to continue the easier and highly profitable policy of accepting generous bribes from both sides.

The revolt in the Hejaz was declared in June 1916. Displaying his usual good business sense, Hussein had already pocketed 50,000 pounds from the Turks to finance a campaign against the British and a further substantial down payment from the British to finance a campaign against the Turks. His commitment to Arab nationalism was in fact only a fig leaf to cover his own territorial ambitions – a fact that was not lost on the British. David Hogarth, the head of the Arab Bureau in the Foreign Office commented acidly: “It is obvious that the king regards Arab Unity as synonymous with his own kingship.”

The revolt of the Hejaz, despite its glorification in the film Lawrence of Arabia, was of a mainly fictitious character. The British spent about eleven million pounds to subsidize it. That would be hundreds of billions in modern money. But they did not get much of a return on their investment. Hogan was forced to admit: “That the Hejaz Bedouins were simply guerrillas, and not of good quality at that had been amply demonstrated even in the early stages; and it was never in doubt that they would not attack nor withstand Turkish regulars.” (Quoted in David Fromkin: A Peace to end all peace, p. 223)

If London did not get a good return on their investment, Hussein got even less for his. The right of self-determination of small nations is merely the small change of imperialist diplomacy. Subsequent events showed that Britain regarded Arab Unity as synonymous with rule from London. The Arabs had been led to expect a great Hashemite kingdom ruled from Damascus. Instead they were handed a few puny little kingdoms, mainly consisting of deserts.

The Hashemites were unceremoniously evicted from Syria by the French. They also lost their ancestral fief of the Hejaz, with the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. This was handed over to the British stooge Abdel Aziz bin Saud, a chieftain from the Nejd, who founded Saudi Arabia in cahoots with his Wahhabi religious zealots, the authentic fathers of today’s ISIS.

One branch of the Hashemites went on to rule Iraq, but the king, Faisal II, was overthrown in 1958. Another branch still survives in the Hashemite Kingdom Jordan (which was then called Transjordan) sliced off from Palestine by the British.

The Sykes-Picot deal

Secret diplomacy is not the exception but the rule in dealings between imperialist powers. This is entirely logical, since the purpose of diplomacy is to deceive both the enemy and public opinion about one’s real intentions and disguise the most sordid interests with honeyed phrases about humanitarian missions, preserving peace, defending democracy and upholding the rights of small nations. Diplomacy is both politics and war by other means. It is cynicism raised to the level of a work of art.

The military setbacks in Gallipoli and Mesopotamia did not for one moment interrupt the normal workings of civilized diplomacy. Hidden from the public view, the Allied robbers busied themselves with the noble and lucrative task of dividing up the spoils. Even before the First World War Egypt, North Africa and stretches of the Arabian Gulf had already been divided up as colonies or protectorates of the European imperialist powers. Now the latter could finish the job.

In late 1915 and early 1916a young British politician, Sir Mark Sykes, chief adviser to the Asquith government on the Near East and a French lawyer-turned-diplomat, Francois Georges-Picot were haggling the terms of a secret deal to carve up the Arab lands of the Ottoman Empire like two men haggling over the price of herrings in a market place. Haggling is a complicated business. It consists essentially in a conflict of wits that has for its aim to deceive, mislead and cheat the other party into accepting a deal that is essentially contrary to his or her interests. It is like a game of chess or, more correctly, poker. Only the stakes tend to be far higher, and the danger to the loser comparably higher.

Sykes actually had a high regard for the cultured Turkish rulers of the Ottoman Empire. By contrast, he held the Arabs whom the British were attempting to rouse against the Turkish yoke in complete contempt. He described the town Arabs as “cowardly”, “vicious yet despicable”, while the Bedouin Arabs were “rapacious…greedy animals.” Here we can hear the authentic voice of imperialism, in which contempt for the lower classes becomes mingled with overt racism.

By contrast, Sykes’ admiration for the Turks is the expression of a kind of upper class solidarity. The representative of British imperialism has no problem identifying with the Turkish overlords who have enslaved millions of Arabs, just as the British ruling class has enslaved millions of Indians and Africans. Slaves deserve to be slaves and rulers are destined to be rulers. Naturally, Sykes’ good opinion of the men in Constantinople does not prevent him from preparing to rob of all their land and assets. Solidarity between robbers can only be stretched so far…

Between the French- and British-ruled blocs, large, mostly desert areas were apportioned to the two powers’ respective spheres of influence. Later, in 1917, Italian claims were added, but they arrived too late at the table of the victors, after the main course had been served and got only the left-overs.

A poisonous legacy

The only aim of the negotiations was the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire. At one point there was the possibility of reaching a deal with the Turks that satisfied both the British and Russians. But the French put a stop to that. They demanded not only control of Syria but of Turkey itself.

In the end it was agreed that Russia would get Constantinople, the territories adjacent to the Bosporus strait (thus giving Russia the sea passages from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean) and four provinces near the Russian borders in east Anatolia (including Armenia). The British would get Basra and southern Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) and the French would get a slice in the middle, including Lebanon, Syria and Cilicia (in modern-day Turkey). Palestine would be an “international territory” – whatever that might mean.

Italy was given control of Turkey’s southwest and Greece was allocated control of Turkey’s western coasts. But as always, the final result would be decided not by a scrap of paper but by the unpredictable fortunes of war. The defeat of the Ottoman armies finally came in in 1918. But then the Turks gave the Allies a disagreeable surprise. The Greek army, with the tacit support of the Entente, invaded Turkey, believing that there would be little or no resistance. But the Turkish forces regrouped and under Kemal Pasha Ataturk, driving the invaders out of Anatolia in great disorder.

The result was the barbaric expulsion of the Greek population of Asia Minor, which generated feelings of mutual hatred and fear between Greeks and Turks that has poisoned relations between the peoples for generations. In the same way the bloody conflict between Arabs and Jews can be traced back to these dirty deals of the First World War.

During the war, Britain had promised Palestine to both the Arabs and the Jews. In the end neither got what they wanted. Even while Britain was negotiating with Sharif of Mecca Hussein bin Ali, the foreign secretary, Arthur Balfour wrote a letter to Baron Walter Rothschild, a close friend of Zionist movement leader Chaim Weizmann, promising to establish “a national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine (November 2, 1917).

The standpoint of imperialism was clearly expressed by the British Prime Minister Lloyd George in a secret session of the House of Commons on 10 May 1917, when he shocked the House by his bluntness:

“The Prime Minister intended to deny France the position that Sir Mark Sykes had promised her in the post-war Middle East, and took the view that the Sykes-Picot agreement was unimportant; that physical possession was all that mattered. Regarding Palestine, he told the British ambassador to France in April 1917 that the French would be obliged to accept a fait accompli. ‘We shall be there by conquest and shall remain.’” (David Fromkin, op. cit. p. 267, my emphasis, AW)

One could not wish for a clearer exposure of the brutal reality of imperialist politics and diplomacy: might is right; what we have we hold. It was expressed far more eloquently long ago by Heraclitus when he said: “War is father of all and king of all; and some he manifested as gods, some as men; some he made slaves, some free”

As Lloyd George had predicted, Palestine was pocketed by Britain, along with a huge slice of the former Arab territories of the Ottoman Empire. France got most of what was left. Mosul was at first apportioned to France, but finally was handed over to Britain, which joined it to the future Iraq. The Jews got a slice of Palestine, but not the Jewish homeland that the British had promised them. As for the unfortunate Kurds, who aspired to a state for themselves, their claims were completely ignored and they were split up between four countries (Syria, Iraq, Turkey and Iran).

To keep the French quiet, Syria was handed over to them. They also had effective control Greater Lebanon, although it was nominally in the hands of the Maronite Christians. Given the complex mixture of faiths and ethnic groups in that small country, that was a recipe for future instability and chaos.

After the October Revolution, the Bolsheviks found a copy of the Sykes-Picot agreement in the government archives. Leon Trotsky published a copy of the agreement in Izvestia on November 24, 1917, exposing the real plans of the great powers to carve up the Ottoman Empire. Lenin called it “the agreement of colonial thieves.” There is not a lot one could add to that accurate and succinct definition.

The consequences of all this are still with us today. By dividing this most volatile region into artificial states cutting across through ethnic and religious boundaries, the Sykes-Picot agreement guaranteed a future plagued by wars and conflicts. The crimes of imperialism have left a poisonous legacy, which has reduced the most promising parts of the Middle East to a pile of smoking ruins. In the words of the Roman writer Tacitus:

“They have created a wilderness and they call it peace.”

To be continued…