The tensions between the major European Powers, which were ultimately rooted in the struggle for markets, colonies and spheres of interest, were increasing steadily in the decades before 1914. They found their expression in a series of “incidents”, each of which contained the potential for the outbreak of war. If they did not reach this logical conclusion that was because the objective conditions were not yet sufficiently mature. In August 1914 came the “tipping point” and the Great Slaughter began.

Some thirty years ago the Danish physicist Per Bak wondered how the exquisite order seen in nature arises out of the disordered mix of particles. He found the answer in what we now know as phase transitions, the process by which a material transforms from one phase of matter to another, such as the transition from water to steam or from steam to plasma. The precise moment of transition — when the system is halfway between one phase and the other — is called the critical point, or, more colloquially, the “tipping point.”

In studying avalanches, Per Bak used the analogy of sand running from the top of an hourglass to the bottom. The sand accumulates grain by grain until the growing pile reaches a point where it is so unstable that the addition of a single grain may cause it to collapse in an avalanche, which may be big or small. When a major avalanche occurs, the base widens, and the sand starts to pile up again, until the next critical point is reached. But there is no way to tell whether the next grain to drop will cause an avalanche or just how big an avalanche will be.

In point of fact, this idea was discovered long ago and found its most comprehensive exposition in Hegel’s Logic. Modern science has proved beyond doubt that the law of the transformation of quantity into quality has a ubiquitous character and is present in a vast number of cases throughout the universe. There are tipping points not only in avalanches and nuclear reactions but also in heart attacks, forest fires, the rise and fall of animal populations, the movement of traffic in cities and many other spheres.

Despite all the stubborn attempts of the subjectivists to exclude human society from this general law, history furnishes a vast number of instances that prove that quantity turns into quality repeatedly. The same dialectical law can be observed in such phenomena as stock exchange crises, revolutions and wars. What happened in 1914 is a very good example of this.

The tensions between the major European Powers, which were ultimately rooted in the struggle for markets, colonies and spheres of interest, were increasing steadily in the decades before 1914. They found their expression in a series of “incidents”, each of which contained the potential for the outbreak of war. If they did not reach this logical conclusion that was because the objective conditions were not yet sufficiently mature. These incidents are similar to the small landslides that precede a major avalanche in the above example.

The First World War could have broken out on several occasions before 1914. In 1905-6 an international crisis erupted when Germany clashed with France over the latter’s attempts to get control over Morocco. In 1904 France had concluded a secret treaty with Spain for the partitioning of Morocco, having also agreed not to oppose Britain’s moves to grab Egypt. This deal between two robbers, however, enraged another would-be robber, Germany. Under the hypocritical guise of supporting an “open-door” policy in the area (which meant leaving the door open for the German robbers). Berlin was preparing to establish its own control in the region.

In a typically theatrical display of imperial power, Kaiser Wilhelm II visited Tangier. From the comfort of the imperial yacht on March 31, 1905, he declared his support for the independence and integrity of Morocco. This was the cause of the First Moroccan Crisis. It provoked an international panic, which was resolved the following year by the Algeciras Conference. A gentleman’s agreement was reached between the different robbers whereby Germany’s economic rights were recognized, while the French and Spanish robbers were allowed to “police” Morocco. Naturally nobody ever asked the people of Morocco whether they either needed or desired such policemen on their streets, but they got them anyway.

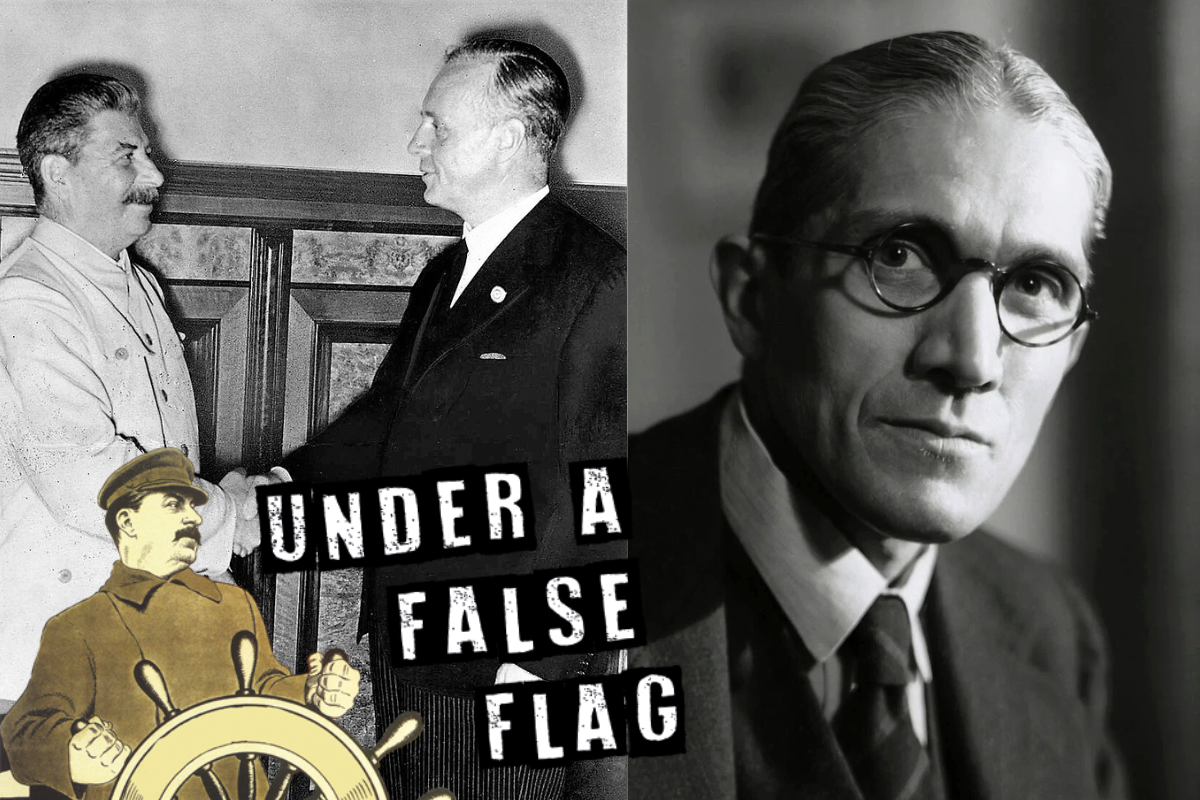

The view from London

Sir Edward Grey was appointed British Foreign Secretary in the middle of the First Moroccan Crisis and remained in office until the outbreak of war. The Entente Cordiale between Britain and France was still recent and it was clear that by stepping on the toes of French imperialism in North Africa, Germany was trying to test the new partnership or even destroy it. Berlin’s aim was to isolate France, expose Russia’s weakness, and British perfidy. Britain would have to decide whether or not to stand by the French. In the end it was compelled to do so.

The most important thing for British imperialism was to ensure its rule in Egypt. As part of the deal London would support France in Morocco. If Britain had remained neutral in this conflict, the Entente Cordiale would have been as dead as a dodo and France and Russia might even move closer to Germany against Britain. Grey warned that ‘the French will never forgive us… Russia would not think it worthwhile to make a friendly arrangement with us about Asia… we should be left without a friend and without the power of making a friend and Germany would take some pleasure… in exploiting the whole situation to our disadvantage’. (Beryl Williams, Great Britain and Russia, 1905-1907, in Hinsley,British Foreign Policy Under Sir Edward Grey, pp.133-4)

Nevertheless, Britain was still reluctant to get involved in any war on the European Continent and Grey did everything in his power to avoid any diplomatic commitment that could lead to such an entanglement. London entered into an agreement with Russia, while assuring Germany that there was no intention to encircle it. Although that was indeed the intention, he was anxious not to arouse German suspicion – which might provoke Germany into a war to destroy a hostile and threatening encirclement.

There were new tensions in the Balkans in 1907 when Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia and Bulgaria declared its independence, which led to a diplomatic clash between Austria and Russia. But still reeling from a humiliating defeat in the war with Japan and the 1905-6 Revolution, Russia backed down.

The Agadir Incident

On February 8, 1908, a new deal was signed between the French and German robbers, in which they solemnly ratified Morocco’s independence, while at the same time recognizing France’s “special political interests” and Germany’s “economic interests” in North Africa. But robbers are never satisfied and are always casting envious glances at the loot in the other man’s bag. Not long afterwards the Second Moroccan Crisis (the Agadir Incident) exploded. This time, instead of the Kaiser’s yacht, the Germans dispatched the gunboat Panther.

In April 1911, contravening the Algeciras Act, France despatched troops to Fez to suppress an uprising by the “natives”, who were apparently somewhat dissatisfied with the services of their foreign policemen. In response, the Germans sent the Panther to Agadir on July 1. It was not that Berlin objected to the French killing Arabs. On the contrary, they backed it. But this action, taken allegedly to protect German interests, was in reality intended to intimidate the French. The robbers in Berlin demanded compensation from the bandits in Paris for keeping their nose out of Morocco.

Once again the international scene was racked by tension. The threat of war was in the air. The British even started to make preparations for war. But conditions for an all-out war had not yet ripened sufficiently and once again a diplomatic solution was found. The robbers argued over a division of the colonial spoils. Behind the scenes its real aim was to split the Entente.

The gentlemen in London were annoyed that France had disturbed the status quo. This was decidedly “not cricket”. The British were inclined to the view that Germany was entitled to compensation – as long as someone else paid the bill. On the other hand, British interests demanded that the Entente be preserved and French toes be not trodden upon. A tricky situation, yes, indeed!

Germany wanted to humiliate France by demanding the whole of the French Congo in return for German non-intervention in Morocco. Such a demand, as Eyre Crowe remarked, was “not such as a country having an independent foreign policy can possibly accept”. Since Britain held the balance in Europe, it was able to twist arms in Berlin, as well as in Paris, to get what it wanted: the preservation of the European equilibrium and the avoidance of war, which was a distinct possibility at that time. In the end, France was given the right not just to police the ungrateful Moroccans but to exercise a protectorate over them. In return, the Germans were thrown a few scraps of territory from the French Congo.

Morocco’s old colonial masters in Spain naturally complained at this grossly unfair decision; but a disapproving growl from the British lion was enough to silence them. The French were very happy, the Germans much less so, the Spanish less still. But the British were satisfied and war had been averted. As for the Moroccans and Congolese, nobody thought their views on the subject worth recording.

The Naval Question

The Agadir Incident had carried Europe to the brink of war. But of far more fundamental importance to the interests of British imperialism was the alarming growth of German naval power. A basic principle of London’s foreign policy was that Britain must have naval superiority. But attempts to get Germany to limit its programme of naval expansion only aroused resentment and hostility in Berlin, which offered only to slow the pace of naval expansion, and then only on condition that Britain would remain neutral in a European war. The British refused to give any such undertaking, which would have alienated France and Russia and left her powerless and isolated.

The attempts of British diplomacy (the Haldane Mission) to placate Germany only created an impression of weakness, and weakness invited aggression. Admiral von Tirpitz replied angrily that he would not accept the suggestion of a reduction of his fleet by even a single ship. To persist in negotiations when there was nothing to discuss was an act of stupidity that merely served to convince the generals and politicians in Berlin that Britain would not fight in a European war, an idea that persisted right up to the summer of 1914 and played a fatal role in Germany’s calculations.

They went on to haggle over colonial and territorial exchanges like merchants in the market place. Germany agreed to give Britain a controlling interest in the southern section of the Baghdad Railway in return for Zanzibar and Pemba and a slice of Angola. But these were minor matters of entirely secondary importance. By accepting the German offer of a reduction in the tempo of naval construction instead of reducing the size of the German navy, Haldane gave von Tirpitz and the Kaiser what they wanted and got almost nothing in return.

Emboldened by their success, the Germans again demanded British neutrality in a European war. Sir Edward Grey prevaricated. Instead of rejecting this insolent demand out of hand, he suggested an ambiguous formula to the effect that: “England shall neither make nor join in any unprovoked attack upon Germany”.

Here we have a truly classical example of the meaningless language of the diplomatic Pharisees. What is the meaning of the word unprovoked? The very notion of a promise not to make an unprovoked attack is absurd, since every country will decide to go to war whenever it suits their interests to do so, and provocations are the easiest things in the world to manufacture.

In underlining that word “unprovoked”, Grey was resorting to diplomatic trickery, angling to cast British imperialism as arbiter in a future conflict between France and Germany and not a combatant. But once again this showed weakness and confirmed the belief in Berlin that in the event of war, Britain would not want to fight. Far from saving Britain from war, it brought war a lot closer.

Britain and Germany

By 1914, Germany was the strongest continental power, economically, industrially, demographically and militarily. The most industrialized country in Europe, with a powerful army and navy, Germany was a young, vigorous and rising nation, ambitious to acquire the status of a world power. But its actual status vis-à-vis the old established European powers was not at all commensurate with its economic and military weight.

In a 1907 New Year’s Day memorandum, Sir Eyre Crowe the foremost expert on Germany at the British Foreign Office formulated the question approximately thus: The world belongs to the strong. A vigorous nation cannot allow its growth to be hampered by blind adherence to the status quo. It was therefore foolish to suppose that Germany would not to want to expand. The ruling circles in London were therefore under no illusions that war with Germany would be inevitable.

While German capitalism was on the rise, Britain was entering into a phase of relative decline. Glutted by the plunder of Empire, Britain was extraordinarily wealthy, but its industries were increasingly outclassed by Germany and other competitors. Its vast global Empire was difficult to defend, its huge navy overstretched. Its share of world trade was in decline, although the value of her exports was boosted by her dominance in the “invisible” trades and huge overseas investment. More than any other nation, Britain was dependent on international trade.

In principle, the British bourgeoisie was interested in preserving peace – which is only another way of saying preserve the status quo. However, it was in the interest of British imperialism to prevent any particular power from gaining hegemony. For centuries, Britain had fought to maintain the balance of power in Europe, to ensure that no state achieved domination in the European mainland. The Kaiser’s Germany was becoming a threat to that scheme.

If France had been defeated, Britain would have been faced with the nightmare of a continent dominated by a single, aggressive state. In the given conditions, therefore, Britain would have to back France against Germany to prevent the latter achieving dominance. This was the cornerstone of the policy of Sir Edward Grey, the British Foreign Secretary.

To cover these cynical calculations the British government naturally put forward “democratic” war aims, offering the idea of some sort of self-determination for the nationalities within the Austro-Hungarian and Turkish Empires, attempting to appeal to the German people over the heads of the Imperial government. But this was just a smokescreen. The real attitude towards self-determination was shown by the comments of the Manchester Guardian, which wrote that if only it were possible, the best thing to do with Serbia would be to tow it out to sea and sink it.

It is interesting to compare the character of Wilhelm to that of the British foreign minister Sir Edward Grey. The contrast between the unflappable, phlegmatic, almost somniferous Grey and the pushy, arrogant, impulsive Kaiser is striking. Grey has been criticized by many historians for his apparent apathy and lack of initiative. Throughout all this atmosphere of diplomatic frenzy and hysteria, the British government and its foreign minister appear curiously aloof. When, after the assassination in Sarajevo, the foreign minister showed no outward signs of alarm and only slight interest: yet another muddle in the Balkans that need not concern us, and that will soon blow over, and so on.

In the weeks leading up to the declaration of war, Grey manoeuvred constantly between France, Germany, Russia and Austria, putting forward various schemes for mediation in the conflict between Austro-Hungary and Serbia and fobbing off the insistent demands of the French with evasive answers. Almost until the eleventh hour the British Foreign Secretary appeared to show little concern about the urgency of the situation, adopting a wait-and-see attitude, apparently more interested in what was for dinner in his club than the spicy dishes that were being brewed in the Balkans.

This seemingly organic indecision, which infuriated allies, enemies and colleagues alike, may or may not have been an integral part of his personality (there are some people for whom vacillation is second nature), but it was a faithful reflection of the interests of British imperialism. In fact, the temperamental differences between Wilhelm and Grey reflected the differences between Britain, an old established Empire, and Germany, the upstart with a mighty industrial base and a powerful army and navy, which was blocked and frustrated on all sides by its rivals.

What was involved was a fight between two robbers for a more equitable share-out of the loot. One robber was already in possession of half the world and had no wish to be disturbed in the enjoyment of its plunder. The other robber was gnawed by envy at his neighbour’s wealth and thirsted to lay his hands on it. It was not in the interests of British imperialism to be dragged into a land war in Europe but rather to let others do the fighting. For Germany, on the contrary, a war with Russia and its French ally was not only desirable but absolutely necessary. If it were possible to keep Britain out of it, that would be obviously desirable. But if it meant war with Britain, so be it.

Behind the facade of indifference, British imperialism was engaged in a complicated manoeuvre, as Trotsky points out:

“English diplomacy did not lift its visor of secrecy up to the very outbreak of war. The government of the City obviously feared to reveal its intention of entering the war on the side of the Entente lest the Berlin government take fright and be compelled to eschew war. In London they wanted war. That is why they conducted themselves in such a way as to raise hopes in Berlin and Vienna that England would remain neutral, while Paris and Petrograd firmly counted on England’s intervention.“Prepared by the entire course of development over a number of decades, the war was unleashed through the direct and conscious provocation of Great Britain. The British government thereby calculated on extending just enough aid to Russia and France, while they became exhausted, to exhaust England’s mortal enemy, Germany. But the might of German militarism proved far too formidable and demanded of England not token but actual intervention in the war. The role of a gleeful third partner to which Great Britain, following her ancient tradition aspired, fell to the lot of the United States.” (Trotsky, The First Four Years of the Communist International, vol.1 p.60)

The final outcome was decided by the underlying irreconcilable contradictions. The Austrian ultimatum to Serbia in July 1914 put an end to this diplomatic game. Grey’s manoeuvres had reached their limits. On 3 August, Grey told the House of Commons that although Britain was not legally bound by the Entente Cordiale, it had a “moral obligation” to stand by France. Britain could not stay out of a war that it knew was inevitable.

The tipping point

Events now reached the tipping point at which there can be no turning back. When news of the Russian mobilization reached Berlin at midday July 31 Germany had the excuse it needed to proclaim a state of “threatening danger of war”. The “Cossack menace” gave the Kaiser and his generals the green light to justify before the German people and world opinion to move against Russia and her ally France. Here again the question of who fires the first shot is of no importance. German imperialism was acting in accordance with war plans that had been drawn up a long time before.

In response, France ordered military preparations for the protection of her frontier with Germany, though no troops were to move closer than about six miles to the German border. All this time the French president was straining every muscle and nerve to get Britain to declare her intention to support France in the face of the threat from Germany. But the British, to the furious indignation of the French, remained stubbornly non-committal, at least in public, intending to keep their hands free until the last minute and avoid any firm commitment.

In a desperate attempt to secure such a commitment, the French government assured London that “France, like Russia, will not fire the first shot”. But “who fired the first shot” can never determine who was really responsible for a war, or even who the aggressor was and who the victim. It is always possible to manufacture an incident, to provoke someone into firing the first shot and thus to convince public opinion that the aggressor is really the victim and the victim is really the aggressor.

From the standpoint of British imperialism the most crucial question was Belgium. The insistence on Belgian neutrality was, however, not dictated by sentimentality or any attachment to the sacred principle of self-determination. Britain was concerned about Belgium only to the extent that if the Belgian ports fell into the hands of an enemy power, that would present a serious threat to British naval supremacy and hence the security of Britain itself. That is the real reason why the British ruling class, had no real option but to enter the War.

The British issued a memorandum to France and Germany requesting assurances that Belgian neutrality would be respected. France gave an immediate unqualified assurance. Germany ignored the request. Threatened to the East by the Russian mobilization, the German General Staff had already decided to deliver a crushing blow to the West, defeat France and knock her out of the war before the mighty Russian army had a chance to cross Germany’s eastern frontier.

Since the French had taken the precaution of strengthening their frontier defences against a German attack, the only logical road to take was through neutral Belgium. In London yet another tense conversation took place between Grey and the French ambassador, Paul Cambon, in which the latter asked whether England would help France if she were attacked by Germany. Even at this late hour Grey’s reply was evasive: “…as far as things had gone at present… we could not undertake any definite engagement.” France and Germany were kept guessing as regards Britain’s intentions.

Now it was Germany’s turn to ask France to declare its intentions, and to do so within 18 hours. France replied cryptically that she would “act in accordance with her interests”. In practice there is nothing the French could have done to avert the danger of war. It was later revealed that if France had opted for neutrality, Germany would have demanded the turning over to Germany of her vital frontier fortresses of Toul and Verdun, to be held as a pledge of French neutrality until the end of the war with Russia. It was the tale of the wolf and the lamb all over again, except that in this case it was the tale of two rival wolves snapping and snarling at each other, one older and fatter, the other leaner and hungrier.

Already on July 26 a document had been drafted in Berlin containing a demand for “benevolent Belgian neutrality”, that is to say, Belgium must give German troops free access to its territory. On August 3 Belgium refused the German demands and Germany declared war on France. The following day, August 4, German troops crossed the Belgian frontier and blasted the Belgian defensive fortifications with heavy artillery. The British reaction was immediate. London issued an ultimatum to Germany. Its rejection meant war with Germany. Two days later Austria declared war on Russia.

The German army advanced, scoring relatively easy victories that gave Germany control over most of Belgium and some parts of northern France with its rich agriculture and important industries. Everywhere the German army looted, burned and pillaged, earning the hatred of the population. In Belgium they shot anyone suspected of being a sniper or of opposing the German army in any way. They took hostages and inflicted brutal massacres of the civilian population.

The German atrocities in Belgium provided the British with a rich supply of gruesome stories about the “Hun brutality”, some true, some invented, all suitably embellished by expert propagandists. These stories were used in much the same way as the media coverage of the Ukrainian civil war: to demonize the enemy, who are presented as inhuman monsters, and thus aid recruitment. But the propaganda about “poor little Belgium” was entirely hypocritical. The British imperialists went to war because they saw German domination of Europe as a threat to Britain’s position in the world and German ambitions as a threat to the British Empire.

In his memoirs Sir Edward Grey mentioned the remark he made on 3 August 1914. It sounded like an obituary for the old world: “A friend came to see me on one of the evenings of the last week — he thinks it was on Monday, August 3rd. We were standing at a window of my room in the Foreign Office. It was getting dusk, and the lamps were being lit in the space below on which we were looking. My friend recalls that I remarked on this with the words: ‘The lamps are going out all over Europe. We shall not see them lit again in our life-time’.”

It was the start of the Great Slaughter.