In the final part in his series on World War One, Alan Woods looks at how the war was brought to an end by revolutionary upheavals across Europe, beginning with Russia in 1917 – a fact that has been buried under a mountain of myths, pacifist sentimentality, and lying patriotic propaganda.

For the soldiers, the war was a seemly unending nightmare; for the civilians on the home front, especially the women, hardly less so. In the end large tracts of Europe lay wasted, millions were dead or wounded. The great majority of casualties were from the working class. Survivors lived on with severe mental trauma. The streets of every European city were full of limbless veterans. Nations were bankrupt—not just the losers, but also the victors.

This bloody conflict was brought to an end by revolution—a fact that has been buried under a mountain of myths, pacifist sentimentality, and lying patriotic propaganda. By 1917, in all the belligerent states, the discontent of the masses was growing. In particular the people of Germany were beginning to suffer food shortages that sparked off riots and mass strikes across the country. There were mutinies in the armies and navies of Italy, Austria, France, and Britain. In August 1917 sailors at Wilhelmshaven were the first to mutiny. In Hamburg and Brandenburg, martial law was required to restore order.

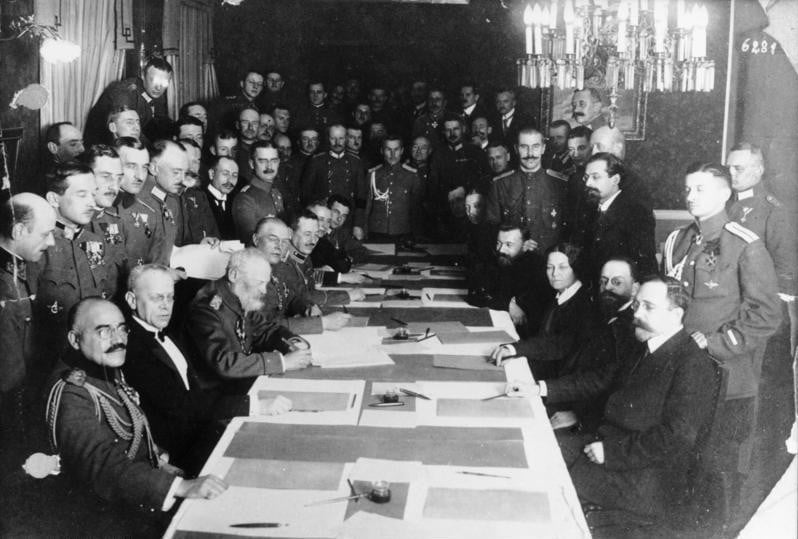

Brest-Litovsk

Internationally, the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 had a profound effect. In the factories and trenches it sounded a clarion call. An urgent priority for the Bolsheviks was to get out of the war. The Russian army was disintegrating. On the Eastern Front there was mass fraternisation between Russian and German soldiers. They met together in no-man’s land and exchanged caps and helmets, shared vodka and schnapps, embraced and danced together. Even some officers joined the festivities.

But the party was not allowed to last. The German general staff realised the danger of this fraternisation and ordered a new advance. The Russian army was in no position to resist. The war-weary peasants in uniform threw away their rifles and deserted en masse to return to their villages. The Russian army was rapidly collapsing. The Germans pushed deep into Russian territory. A truce was hastily called, followed by a peace conference that ended Russia’s participation in the war.

The conference opened in December at Brest-Litovsk (now in Belarus), where the German army had its headquarters. As leader of the Bolshevik delegation, Leon Trotsky skilfully used the negotiations as a platform to launch revolutionary propaganda directed at the soldiers and workers of the belligerent powers. Trotsky strove to stretch the discussions out in the hope of a revolution in Germany and Austria which would come to Russia’s aid. His speeches, which were translated into German and other languages and widely distributed, did have a considerable effect.

The revolutionary events in Russia transformed public opinion in Austria-Hungary. The rebellious mood was reflected in a wave of factory strikes, which forced the government to attend to the workers’ grievances, improving working conditions and easing wartime controls. The January 1918 strikes were the first step on the road to revolution. They had a tremendous effect on the ranks of the army and especially the navy. But the development of the revolution in Austria-Hungary and Germany needed time, and for the Russian Revolution time was running out.

At one point, as a sign of impatience with Trotsky’s delaying tactic, General Hoffmann placed his jackboots on the table. In his memoirs Trotsky later commented that Hoffmann’s jackboots were the only thing that was real in that room. The Bolsheviks had no army to defend the Soviet power. The old tsarist army had practically ceased to exist and the Red Army had not yet been created. Threatened by enemies on all sides, the Bolshevik Revolution was in danger of being throttled at birth.

The German army advanced and seized control of Poland, the Baltic States, and the Ukraine. The Allied powers also intervened: the French in Odessa, the British in Murmansk, and the Japanese in the Russian Far East. Under these circumstances the Bolsheviks were compelled to accept the harsh conditions imposed by German imperialism at Brest-Litovsk. This was a blow, but it gave the Bolsheviks a breathing space, to allow time for the revolution to develop in Europe. They did not have long to wait.

Austria-Hungary

The sailors, being mainly drawn from the proletariat, were particularly active as a revolutionary force, not only in Russia but also in Austria-Hungary and Germany. The warships were like floating factories, and close contact with the officers bred a class hatred that was all the more intense for that. In Austria-Hungary, the first naval revolts began in July 1917 over a disruption of food supplies. An Austrian submarine defected to Italy in October 1917, provoking fear that Austro-Hungarian forces might succumb to the revolutionary moods that affected the Russians.

By January 1918 hundreds of thousands of workers were on strike in Vienna. Revolutionary sailors actively supported the striking workers at the Pola arsenal. The Slovene, Serbian, Czech, and Hungarian troops in the armed forces mutinied. In February a naval mutiny broke out at Cattaro in which the captain of the cruiser Sankt Georg was shot in the head. Mutineers demanded better food and a “just peace” based on President Wilson’s Fourteen Points.

The arrival of three light battleships forced the mutineers to surrender, but the uprising was a warning signal to the government. More than 400 sailors were imprisoned for their role in the mutiny, four of whom were executed. On 27 October 1918, in the final days of the war, unrest again broke out after the Austro-Hungarian army collapsed in the face of an Italian offensive. Naval vessels were soon operating under the control of their crews.

The crumbling edifice of the Hapsburg Empire tottered and fell under the hammer blows of revolution. Between 28 and 31 October 1918, the monarchy collapsed. Its armies were scattered and broken, and new national governments were springing up in the regions. The old Austro-Hungarian state had ceased to exist. Power was lying in the street, waiting for somebody to pick it up. Had there been a Bolshevik Party to take advantage of the situation, the Austro-Hungarian Empire would have gone the same way as its Russian cousin. But the so-called Austrian Marxists were no different than the Russian Mensheviks, and had not the slightest idea of assuming power.

Collapse of Ludendorff’s offensive

Despite the dire state of German morale both at home and in the army, General Ludendorff launched a series of offensives in the spring of 1918 in what was to be a last desperate attempt to break the stalemate on the Western Front. Between 21 March and 4 April 1918, in the first round of these suicidal adventures, German forces suffered over 240,000 casualties. It was a futile waste of life.

By mid-June 1918, it was clear that this last gamble had failed. The Germans paid dearly for this adventure, with final losses of almost a million soldiers. It is true that the losses sustained by the Allies were almost as great, but their numbers were boosted by the arrival of American troops. More than 200,000 fresh soldiers were arriving every month from May to October 1918. By late July 1918, more than one million men were part of the American Expeditionary Force on the Western Front. Germany’s position was now hopeless.

The final Allied push towards the German border began on October 17, 1918. As the British, French, and American armies advanced, the alliance between the Central Powers, already under unbearable strain, began to fall apart. Turkey signed an armistice at the end of October, Austria-Hungary followed on November 3. Germany was left alone in the face of the renewed Allied onslaught.

By the autumn of 1918 the situation in Germany was critical. The German emperor and his military chief, Erich Ludendorff, realised that there was no alternative. Germany must beg for peace. But the situation was already spiralling out of control. Power was slipping out of their hands. After years of suffering, a war-weary and hungry country became rebellious. Discontent and hunger were rife in Germany. The whole country was a powder keg waiting for a spark to set off an explosion.

Faced with the threat of immediate revolution, Prince Max attempted to carry out reforms that would transform Germany into a constitutional monarchy. But things had already gone too far. A rumour that an order had been issued to attack the English fleet in the North Sea sparked off a revolt of the sailors in Wilhelmshaven and Kiel on October 30. Everybody knew that the war was lost. The morale of the sailors was already low rock bottom. Such a suicidal attack, while armistice negotiations were underway, would have been yet another senseless loss of life.

The men passed a resolution stating their refusal to take the offensive. The officers replied by arresting some of the sailors, which led to a mass demonstration of the sailors on November 3. These demonstrations were fired upon, resulting in 8 deaths and 29 wounded. The incident had an electrifying effect on both workers and sailors.

The Kiel workers joined the movement on November 4, creating the first soldiers’ and workers’ council in Germany. From Kiel the mutiny spread quickly to other provinces and cities, such as Lübeck and Hamburg. In Cologne the councils were established within days. There was little resistance. The revolutionary councils demanded an end to the war, the abdication of the Kaiser, and the declaration of a republic.

The Council demanded the release of political prisoners, freedom of speech and press, abolition of censorship, better conditions for the men, and that no orders be given for the fleet to take the offensive. On November 5 one northern newspaper wrote, “The revolution is on the march: What happened in Kiel will spread throughout Germany. What the workers and soldiers want is not chaos, but a new order; not anarchy, but the social republic.” The German Revolution had begun.

The German Revolution

Within only a few days the revolt spread throughout the empire with little or no resistance from the old order. Everywhere the workers joined forces with the troops in an unstoppable mass movement against the hated monarchical regime. Throughout the empire, Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils were formed and moved to take power into their hands. But which party was prepared to take power?

Within only a few days the revolt spread throughout the empire with little or no resistance from the old order. Everywhere the workers joined forces with the troops in an unstoppable mass movement against the hated monarchical regime. Throughout the empire, Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils were formed and moved to take power into their hands. But which party was prepared to take power?

The Social Democratic Party had the support of most workers. They now put themselves at the head of the revolution. But in 1917 it had split into the Majority Social Democratic Party of Germany (MSPD) and the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD). On October 5, 1918, the Independent Socialists issued a call for a socialist republic. In Berlin a committee of revolutionary shop stewards was formed and began to collect arms.

In Bavaria on the 7th November 1918 a mass demonstration of thousands of workers demanded peace, bread, the eight-hour day, and the overthrow of the monarchy. The next day the Independents organized a Constituent Soldiers’, Workers’, and Peasants’ Council, and this body proclaimed the establishment of a Bavarian Democratic and Social Republic, headed by Kurt Eisner.

Under the pressure of the masses, the socialist ministers resigned en masse from the cabinet of Prince Max. The Greater Berlin Trade Union Council threatened a general strike if the emperor did not abdicate. The general strike and mass demonstrations were called on the morning of November 9. A Workers’ and Soldiers’ Council was formed, and the regiments and troops stationed in Berlin were won over to the side of the revolution.

In spite of these facts and the reports from his military advisors indicating that his support, even in his entourage, was rapidly evaporating, Wilhelm continued to equivocate over abdication. Even if he was forced to give up the imperial throne, this deluded man believed he could remain as King of Prussia. Such pathetic delusions are always the last refuge of a regime facing the prospect of imminent overthrow.

A deputation of Majority Socialists, including Ebert and Scheidemann, went to see Prince Max. They informed him that the troops had joined the revolution and that a new democratic government had to be formed. Ebert was asked whether he wanted to take power on the basis of the constitution or the Soldiers’ and Workers’ Council. Prince Max had no choice but to announce the abdication of the kaiser, although no word had been received from that quarter. Prince Max then handed over his office to Ebert, and the latter declared himself Reich chancellor.

The Social Democrats in power

In a state of panic, the German ruling class hastily handed power to the only people who they thought could control the working class. They transferred parliamentary leadership to the right-wing Social Democrats under Friedrich Ebert, who was working in cahoots with the army. Ebert believed that the simple transfer of power from Prince Max to himself represented the final victory of the revolution. For these gentlemen, the whole purpose of the revolution was merely to bring about a ministerial reshuffle at the top. Ebert would even have been satisfied with a constitutional monarchy as long as the new state was given a baptismal blessing by a constituent assembly.

That was the mentality of those who sat in comfortable ministerial seats. But the mood in the streets was very different. Was it for this that the workers and soldiers had fought and died? The working men and women soon delivered a resounding answer. The carefully planned scenario in the corridors of power was immediately rendered obsolete by the movement of the masses. A mass demonstration of Berlin workers surrounded the Reichstag building, forcing the Socialist leaders to react. At 2:00 p.m. on November 9, the Social Democrat Philipp Scheidemann mounted the balcony and proclaimed to the crowd:

“These enemies of the people are finished forever. The Kaiser has abdicated. He and his friends have disappeared; the people have won over all of them, in every field. Prince Max von Baden has handed over the office of Reich chancellor to representative Ebert. Our friend will form a new government consisting of workers of all socialist parties. This new government may not be interrupted in their work, to preserve peace and to care for work and bread. Workers and soldiers, be aware of the historic importance of this day: exorbitant things have happened. Great and incalculable tasks are waiting for us. Everything for the people. Everything by the people. Nothing may happen to the dishonour of the Labour Movement. Be united, faithful, and conscientious. The old and rotten, the monarchy has collapsed. The new may live. Long live the German Republic!”

When Scheidemann came in from the balcony, he was met by a furious Ebert. “You have no right to proclaim the republic!” Ebert shouted. “What becomes of Germany—whether she becomes a republic or something else—a constituent assembly must decide.” But the masses had compelled the Majority Socialists to proclaim a republic before the Constituent Assembly had even met. In his memoirs Scheidemann says that he made this speech in order to frustrate Liebknecht’s proclamation of a soviet republic and Ebert’s secret plan to restore the monarchy.

Still living in the clouds, as doomed monarchs tend to do, Wilhelm asked Defence Minister Wilhelm Groener and military chief Paul von Hindenburg what he should do. To his astonishment, they informed the Kaiser that the military could no longer support him. The very next day, November 10th, he boarded a train and fled to the Netherlands, where he would remain until his death in 1941. Allied demands for his extradition and trial were ignored by the Dutch monarch.

The end of the war

The First World War was thus ended by the German Revolution. At this point it was a bloodless revolution. Only 15 people lost their lives in Berlin on November 9. We must compare this with the huge numbers who were slaughtered like cattle on the killing fields of Ypres, Passchendaele, and the Somme. The new German government accepted the inevitable. There was no way Germany could continue the war.

The First World War was thus ended by the German Revolution. At this point it was a bloodless revolution. Only 15 people lost their lives in Berlin on November 9. We must compare this with the huge numbers who were slaughtered like cattle on the killing fields of Ypres, Passchendaele, and the Somme. The new German government accepted the inevitable. There was no way Germany could continue the war.

The Social Democratic leaders had the illusion that they would be treated honourably by the victors. They were sadly mistaken. Had Ebert and Scheidemann paid more attention to Roman history, they would have remembered the chilling words spoken by the chieftain of the Gauls who sacked Rome: Vae victis!—Woe unto the defeated! The French and British treated the German delegation with complete contempt. They were not prepared to listen to even the most modest proposals for compromise.

Not conciliation, but revenge was on the order of the day. The French imperialists were particularly vindictive. The signing of the Armistice took place not in Paris, but in the Forest of Compiègne, about 37 miles (60 km) north of the French capital. The venue, chosen by Ferdinand Foch, a French military commander, was not the marble halls of Versailles but his own railway carriage. This nice little touch was calculated to deepen even further the humiliation of the Germans.

On 11 November an armistice was signed that formally ended hostilities. With Foch’s jackboot on their necks, the German delegation swallowed hard and signed the terms dictated by the French Marshall. The following communique was issued:

Official Radio from Paris—6:01 a.m., Nov. 11, 1918. Marshal Foch to the Commander-in-Chief.

1. Hostilities will be stopped on the entire front beginning at 11 o’clock, November 11th (French hour).

2. The Allied troops will not go beyond the line reached at that hour on that date until further orders[signed]

MARSHAL FOCH

5:45 a.m.

This was essentially a German surrender. The terms of the Armistice were severe. Germany was ordered to give up 2,500 heavy guns, 2,500 field guns, 25,000 machine guns, 1,700 aeroplanes, and all the submarines they possessed (as a matter of fact, they were asked to give up more submarines than they possessed). They were also asked to surrender several warships and disarm all of the ones that they were allowed to keep. Germany was to be rendered defenceless. If Germany broke any of the terms of the Armistice, such as not evacuating areas they were ordered to evacuate, or not handing over weapons or prisoners of war in the timescales given, fighting would recommence within 48 hours.

The Armistice was followed by the predatory Treaty of Versailles. Germany was forced to accept the blame for the First World War and agree to pay reparations, estimated at around £22 billion ($35 billion, €27 billion) in current money. It was only in 2010 that Germany paid off its war debt, with a final payment of £59 million ($95 million, €71 million). The systematic plundering of the German people plunged the defeated nation into a deep economic, social, and political crisis that finally ended with the victory of Hitler and a new and even more terrible world war.

Little did the victors of World War I imagine that just over two decades later, in 1940, another armistice would be signed in the very same railway carriage in the Forest of Compiègne. But this time it was Germany forcing France to sign an agreement to end the fighting on their terms. Adolf Hitler sat in the same seat that Marshall Foch had occupied in in 1918. The carriage was taken and exhibited in Germany as a war trophy. It was finally destroyed in 1945.

The Social Democrats betray

As the deafening roar of artillery was silenced and the thick smoke of gunfire lifted, the workers and soldiers of the former belligerent nations looked up and saw their former enemies in a new light. The Russian Revolution shone like a beacon of light amidst the darkness. Had the German Revolution of 1918 followed the example of the Russian Revolution, the whole history of the world would have been transformed.

But because of the policies of the labour leaders, it was not carried out to the end, and was finally defeated. Liebknecht and Luxemburg established the new German Communist Party on 30 December 1918. But they were still a minority, as Lenin and the Bolsheviks had been in the first months of the Russian Revolution. By an irony of history, it was right-wing German Social Democrats, the same men who had betrayed the working class by voting for the war credits in 1914, who were thrown up by the first impulsive movement of the German Revolution and stood at its head.

For Ebert and Scheidemann, like the Mensheviks in Russia, the achievement of a bourgeois republic was the end of the matter. They wanted to avoid any threat of a Bolshevik-style revolution. The kaiser was gone, but the essential infrastructure of the old imperial state remained intact: the bureaucracy, the power of the military, the church, and the old elite remained firmly in place.

But others thought differently. The Spartacists under Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, nominally part of the Independent Social Democrats, proclaimed a Soviet Socialist republic the same day. The workers’ and soldiers’ councils existed side by side with a bourgeois National Constitutional Assembly in January 1919. But whereas in Russia the Soviets dissolved the Constituent Assembly, in Germany it was the other way around. Behind the façade of an elected assembly, all the old political and economic institutions remained intact.

Hiding behind the shirttails of the Social Democracy, the reactionary forces began to build a force capable of crushing the revolutionary workers. They recruited demobilized soldiers to form the paramilitary Freikorps, armed gangs dedicated to restoring the status quo and re-establishing “Order”. In January 1919 there was an uprising in Berlin, the Spartacist Revolt, which was brutally crushed. The Bavarian Soviet Republic was drowned in blood.

The defeat of the German Revolution was a turning point in world history. The newborn Hungarian Soviet Republic was crushed by Romanian troops in collusion with the French and British imperialists. Béla Kun’s confused policies contributed to this defeat, and Soviet Russia was too weak and beleaguered to come to the assistance of the Hungarian Soviet Republic. Power passed to the counterrevolutionaries under Miklos Horthy, former Admiral of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, who crushed the workers and peasants under the heel of a White Terror.

Revolution and counterrevolution in Italy

A somewhat similar scenario unfolded in Italy, although it took rather longer and, as in Germany, the work of the counterrevolution was accomplished by internal forces, not a foreign invasion as in Hungary. The social and political divisions engendered by the war effort fractured even further in the revolutionary crisis of 1919–20.

The Italian imperialist bourgeoisie had been persuaded to join the war on the Allied side by tempting offers of new territories that were promised by the Treaty of London in 1915. The treaty encouraged the illusions of the Italian imperialists, their vanity puffed up with dreams of recovering the grandeur of the Roman Empire. But these illusions were soon dashed. The British and French bandits took the lion’s share of the loot and left the Italians with a few crumbs.

There was a wave of mass strikes and factory occupations in Italy. In 1919, one million workers were on strike, followed by another 200,000 in early 1920. In those factories that were still operating, workers elected councils (soviets). By September 1920, 500,000 workers were on strike. Italy teetered on the brink of revolution.

The bourgeoisie, terrified by the threat of revolution, resorted to duplicity, offering to negotiate wage concessions if only the workers would abandon the factories. The ruse worked. The colossal revolutionary energy displayed by the working class dissipated for the lack of a determined revolutionary leadership. The workers ended their strikes, giving time for the ruling class to mobilise the forces of counterrevolution.

The proletariat had thrown down the gauntlet to the bourgeoisie, which was unable to solve the deep contradictions of Italian society. These could only be solved by forces outside the narrow limits of bourgeois democracy: either by the victory of the proletarian revolution, or of fascism. Italian bourgeois democracy had very weak roots. During the war, parliament rarely met. Real power was concentrated in the hands of a tiny clique of politicians, industrialists, and generals.

Fascism was a movement based on the petty bourgeoisie and the lumpenproletariat: embittered army veterans, former army officers and NCOs, the sons of the rich, and assorted declassed elements. With its peculiar mix of chauvinism, imperialism, and social demagogy, it gave a banner under which all the disparate discontented elements could unite and acquire the appearance of unity, discipline, and purposefulness.

The son of a blacksmith, Mussolini started his political life as a member of the Socialist Party. He was initially opposed to Italy’s entry into World War I, but later became a rabid chauvinist. Mussolini attacked the Italian government for weakness over the Treaty of Versailles. He united several right-wing groups into a single force and, in March 1919, formed the Fascist Party. Mussolini’s plebeian origins, his earlier credentials as a socialist, and his talent as a demagogue and mob orator made him the perfect leader for such a movement.

Under the pretext of fighting against the establishment, the main target of fascist violence was the revolutionary workers and peasants. The enraged petty-bourgeois nationalists provided a fertile recruiting ground for the reactionaries. Mussolini had used the fascist gangs as a battering ram to smash the labour movement and save the bourgeoisie from the threat of revolution. But in return for his services, he compelled the bourgeoisie to allow him to place his jackboot on their necks. This he achieved in the theatrical coup d’état known to history as the March on Rome.

Mussolini declared that only he could restore order. The terrified bourgeoisie handed him the power he demanded. He then proceeded to dismantle the institutions of bourgeois democracy, taking the title “Il Duce” (“The Leader”). The failure of the workers’ leaders to take advantage of the revolutionary situation to take power led directly to the victory of fascism in Italy. In Germany, the betrayal of the Social Democratic leaders prepared the way for the rise of Hitler and another, far bloodier and destructive world war.

Can there be another world war?

The question inevitably arises: Can there be another world war? Today the contradictions of capitalism have re-emerged in an explosive manner on a world scale. A long period of capitalist expansion—which bears some striking similarities to the period that preceded the First World War—came to a dramatic end in 2008. We are now in the throes of the most serious economic crisis in the entire 200-year history of capitalism.

Contrary to the theories of the bourgeois economists, globalisation did not abolish the fundamental contradictions of capitalism. It only reproduced them on a far vaster scale than ever before: globalisation now manifests itself as a global crisis of capitalism. The root cause of the crisis is the revolt of the productive forces against the two fundamental obstacles that are preventing human progress: private ownership of the means of production and the nation-state.

On two occasions the imperialists tried to solve their contradictions by war: in 1914 and 1939. Why can this not happen again? The contradictions between the imperialists are now so sharp that in the past they would already have led to war. The question that must be asked is: why is the world not at war once more? The answer is in the changed balance of forces on a world scale.

The tensions that now exist between the United States, China, and Europe in another period would have already led to war. But with the existence of nuclear weapons, and also the horrific array of other barbarous means of destruction—chemical and bacteriological arms—all-out war between the major powers would signify mutual annihilation, or at least a price so terrible as to make war an unattractive proposition, except to ignorant and unbalanced generals who, as long as they remain under the control of the bourgeoisie as a whole, are kept on a very short leash. In the longer term, if the working class suffers a series of severe defeats, that can change. But that is not the immediate perspective in the USA or any other major imperialist country.

The historical period in which we live is a peculiar one. Earlier there were always three or four or more imperialist powers, but after the fall of the USSR, there is only one real giant, the United States. The power of imperial Rome was nothing compared to the United States today. Thirty-eight percent of military spending in the world comes from the US, including the most terrifying weapons of mass destruction. US imperialism is truly the biggest counterrevolutionary power on earth in history.

From a military point of view, no country can stand against the colossal military might of the USA. But that power also has limits. There are glaring contradictions between the USA, China, and Japan in the Pacific. In the past that would have led to war. But China is no longer a weak, backward, semi-colonial nation that could be easily invaded and reduced to colonial servitude. It is a growing economic and military power, which is flexing its muscles and asserting its interests. There is no question of the USA invading and enslaving China! How could it even consider a war with a country like China, when it cannot even respond to the continuous and blatant provocations from North Korea? The question is a very concrete one.

Some analysts are drawing parallels between the situation in Syria and that which existed in the Balkans in 1914. But such comparisons are superficial in the extreme. There are important differences between the position today and that which existed in Lenin’s time. The USA only invaded Iraq after its army had already been severely weakened by a long period of sanctions followed by a US bombing campaign. The Americans marched into Iraq with very little effective resistance.

However, in reality US imperialism burned its fingers badly in Iraq, and also in Afghanistan. The reaction of American public opinion to this meant that it was unable to intervene in Syria. Washington’s weakness was already exposed by its inability to fight with Russia over Ukraine. Subsequently, Russia’s intervention decisively changed the military situation in Syria. In Syria it is now Moscow that decides, and the Americans have been compelled to grit their teeth and accept it. The predictions that these contradictions would end in a new world war between Russia and America have been shown to be baseless.

What about Europe? The drive of German imperialism to establish itself as the dominant power in Europe was the principal cause of the First World War. But today Germany does not need to resort to such methods, because it has conquered what it wants by economic means. There would be no point in Germany invading Belgium or seizing Alsace-Lorraine, for the simple reason that Germany already controls the whole of Europe through her economic might. All the important decisions are taken by Merkel and the Bundesbank, without a single shot having been fired. Maybe France can start a war of national independence from Germany? It is sufficient to pose the question to see immediately its absurdity.

The fact of the matter is that the old pygmy states of Europe long ago ceased to play any independent role in the world. That is why the European bourgeoisie was forced to form the European Union, in an effort to compete with the USA, Russia, and later with China on a world scale. But a war between Europe and any of the above-mentioned states is entirely ruled out. Apart from anything else, Europe lacks an army, navy, and air force. Such armies that exist are kept jealously under the control of the different ruling classes, who, behind the façade of European “unity”, are fighting like cats in a sack to defend their “national interests”.

Under present-day conditions, not war between the European states, but class war in every country of Europe is the prospect that now opens up. The introduction of the Euro, far from leading to greater European integration, served to sharpen the national contradictions. In the past, when the countries of Southern Europe had financial problems, they could devalue their currency. Today they don’t have this option. Instead they are compelled to resort to an “internal devaluation”; that means an attack on living standards. This is happening not only in Greece, but across Europe and throughout the world.

This brings us to the other major factor in the equation: the international class balance of forces. The Second World War was the result of a series of serious defeats of the European working class. Hitler came to power only after a series of defeats of the German revolution (1918, 1919, 1921, and 1923). The Italian workers were under the heel of fascism. Finally, the defeat of the magnificent Spanish working class in 1939 removed the last obstacle to a new war in Europe.

The situation on a world scale is now completely different. The working class has not suffered a serious defeat in any of the major countries. The forces of the labour movement are intact. The peasantry, which provided a massive reserve of reaction, Bonapartism, and fascism in the past, has been reduced to a negligible force in Europe and the USA. The students, who were also a reserve of reaction and fascism, have swung sharply to the left. The white collar workers (civil servants, teachers, doctors, nurses, bank employees, etc.) have joined unions and staged militant strikes, which was unthinkable in the past.

US imperialism was compelled to withdraw from Afghanistan because of the war-weariness of the American masses, and when Obama proposed the bombing of Syria, he was forced to back down for the same reason. There is no appetite in the USA for new military interventions and wars anywhere. This is a serious obstacle in the path to war. This does not mean that wars will not occur—of course, they will. But the political fallout will be considerable.

In the case of Vietnam, the mass movement against the war took some years to develop. With the present undercurrent of discontent in US society, antiwar protests can take off very quickly and acquire a revolutionary content. The general perspective therefore is not world war, but increased class polarisation and conflict within the USA and other countries.

For all these reasons a world war, on the lines of 1914–18 or 1939–45, is ruled out for the foreseeable future. However, that does not mean that the world will be a more peaceful and harmonious place, On the contrary, there will be one war after another, but they will be “small” wars, like the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. That is a sufficiently terrible prospect for the human race.

Revolutionary optimism

About 17 million soldiers and civilians were killed during the First World War. One of those who survived was my grandfather. As I write these lines, I have before me the big old family bible I remember from my childhood. Inside there is an entire page headed with the title Roll of Honour. It is decorated in colour with the flags of our gallant allies: the French, Americans, Belgians, Serbs —and the double headed eagle of tsarist Russia. And here we can read the same infamous slogan that is inscribed on every war memorial in the land: Dulce et decorum est por patria mori (It is sweet and seemly to die for the fatherland).

George Woods entered the war on the first of September 1914, a young enthusiastic volunteer. He is listed as private number 13793 of the Welsh Regiment, and served nine spells of action in France in a period of five years. He was demobilised on 24 March 1919. He left the army a changed man. Inspired by the example of the Russian Revolution, he joined the Communist Party and remained a committed Communist until he died. I learned about the ideas of Marx and Lenin, about the class struggle and the Russian Revolution from him, and I am eternally grateful to him for that and so many other things.

My grandfather, a Welsh tinplate worker, was not alone. The South Wales Miners’ Federation voted to affiliate to the Communist International. In Scotland the Clydeside shop stewards did the same. Out of the bloodsoaked ruins of the Great Slaughter, a new spirit of revolt was born. In all the belligerent countries—in Paris and Berlin, in Vienna and Budapest, in Sofia and Prague—millions of workers were on their feet fighting for change, for a better world, for bread and justice: for socialism.

It is easy to draw pessimistic conclusions from human history in general, and wars in particular. There are always those who draw pessimistic conclusions from the objective situation. Scepticism and cynicism are merely hypocritical expressions of moral and intellectual cowardice. Such people blame the working class for their own impotence and apostasy. Lenin never showed the slightest sign of pessimism when the nightmare of war and reaction seemed never ending. He showed utter contempt for the pacifists who moaned about the evils of war but avoided drawing revolutionary conclusions.

During the dark days of the First World War the situation of the revolutionary forces must have seemed hopeless. Lenin once more found himself isolated in Swiss exile. He was only able to maintain contact with a very small group. But he was not afraid to fight against the stream, convinced that the tide would turn. He dedicated all his strength to educate and train the cadres on the basis of the genuine ideas of Marxism. His masterpiece Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism is an immortal monument to his work in the vital field of theory.

Answering a pacifist who said that war is terrible, Lenin said, “Yes, terribly profitable.” And in the end he was proved right. Contradicting all the pessimistic predictions of the sceptical Cassandras, the imperialist war ended in revolution. The Russian Revolution offered humanity a way out of the nightmare of wars, poverty, and suffering. But the absence of a revolutionary leadership on an international scale meant that this possibility was aborted in one country after another. The result was a new crisis and a new and even more terrible imperialist war.

The great wheel of human history turns continuously. It knows great sorrows and great joys. It is a never ending story of victories and defeats. And it teaches us that any situation, however hopeless it may seem, will sooner or later turn into its opposite, and we must prepare for this. This was expressed most strikingly by Shakespeare when he wrote:

There is a tide in the affairs of men,

Which taken at the flood, leads on to fortune.

Omitted, all the voyage of their life is bound in shallows and in miseries.

On such a full sea are we now afloat.

And we must take the current when it serves,

Or lose our ventures.

Lenin said that capitalism is horror without end. The bloody convulsions that are spreading throughout the world right now show that he was right. All these horrors are the expression of a socio-economic system that has exhausted itself and is ripe for overthrow. Middle-class moralists weep and wail about these horrors, but they have no idea what the causes are, still less the solution. Pacifists and moralists point to the symptoms but not the underlying cause, which lies in a diseased social system that has outlived its historical role.

Now, as then, the conditions are being prepared for an explosive upsurge of the class struggle on a world scale. In the convulsive period that lies ahead, the working class will have many opportunities to transform society. The power of the working class has never been greater than now. But this power must be organised, mobilised, and provided with adequate leadership. This is the main task on the order of the day.

We stand firmly on the basis of Lenin’s ideas, which have withstood the test of time. Together with the ideas of Marx, Engels, and Trotsky, they alone provide the guarantee of future victory. Not world war, but an unprecedented upsurge in the class war is the perspective for the period into which we have entered. The horrors we see before us are only the outward symptoms of the death agony of capitalism. But they are also the birth pangs of a new society that is fighting to be born. It is our task to cut short these birth pangs and hasten the birth of a new and genuinely human society.