“Not a wheel turns, not a lightbulb shines, and not a telephone rings without the kind permission of the working class.”

Ted Grant, founder of the IMT, often repeated these words. What it gets to the heart of is that the whole world keeps going thanks to the working class.

The construction of houses; lorries driving from point A to point B; the delivery of post: the working class keeps society running. Yet it does not run society.

All of this is done as part of an overall system – capitalism – in which the means of production (warehouses, factories, oil and gas rigs, supermarkets, etc.) are the private property of the capitalist class. They own this plant, equipment, and infrastructure. And that means they get to decide what’s done with it.

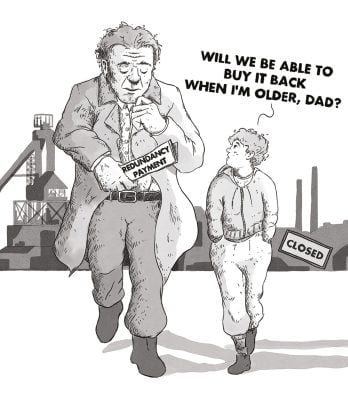

The ongoing dispute at Port Talbot reveals this starkly. Several thousand steelworkers are being thrown on the scrapheap, despite the crucial role they play in production. Their livelihoods, and the whole town’s fate, has been decided by the cruel logic of the market.

None of this production is planned according to the needs of society. Instead, the economy operates chaotically, dependent on whatever maximises profit for the capitalists. That’s why we face redundancies, or are made to work longer, for less, while their profits get bigger year on year.

Nationalisation

In relation to Port Talbot, the demand for nationalisation has been raised by some workers, and in the pages of The Communist. Our comrades are calling for this on the streets and in the labour movement.

We have put forward this demand in conjunction with a call for workers to occupy the steelworks, in order to save it.

Such an occupation would prevent the bosses from rapidly closing the steel plant and asset stripping it. And it would also pose the question starkly: who owns production? And who should control it?

These are important questions for the labour movement to answer. After all, the demand for nationalisation, while necessary, is not enough on its own.

Nationalised industries – past and present – do not automatically provide workers with decent wages and conditions; nor do they necessarily give workers a say in how the workplace is run, or over what is produced.

This was the case with old industries such as coal mining, for example. After all, the miners’ strike of 1984-85 was against both the National Coal Board and the Tory government!

Even today, in the National Health Service, it is clear that state management, under a capitalist state, does not directly result in an improved system, either for patients or staff – as junior doctors, in particular, can attest to.

Quite a few times throughout history, however, workers have started to run their own workplaces under democratic control.

In Britain in the 1970s, there were several cases of this, including the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders in 1971, or the Fakenham shoes factory in 1972. There are many more examples from around the world too.

Business secrets

A first step towards workers’ control begins with workers demanding the opening up and examination of the company’s books. In doing so, workers find out in practice how the capitalists are completely unnecessary – that, in reality, they’re like parasites.

This step is important for revealing what money is spent, and where; exactly how the workforce is being exploited; and how much wealth is being syphoned off to shareholders.

‘Opening up the books’ doesn’t simply apply on a company-by-company basis, but must be carried out across the whole economy. As Trotsky explains in The Transitional Programme:

“The working out of even the most elementary economic plan – from the point of view of the exploited, not the exploiters – is impossible without workers’ control; that is, without the penetration of the workers’ eye into all open and concealed springs of capitalist economy.

“Committees representing individual business enterprises should meet at conference to choose corresponding committees of trusts, whole branches of industry, economic regions and finally, of national industry as a whole.”

Workers’ participation and cooperatives

Sometimes when the demand for workers’ control is raised, people view it as interchangeable with workers’ participation or workers’ cooperatives. But this confuses the matter.

Workers’ participation is common in places like Germany, for example. This is where workers are allowed to put forward representatives to sit alongside the capitalists on a business’ board of directors.

In practice, this binds these workers to the class that exploits them, essentially giving them a limited say in exactly how they should be exploited in the interests of the company ‘as a whole’.

The case of workers’ cooperatives is slightly different. This is when workers may own and manage a company collectively, without any capitalist bosses. Ultimately, however, such enterprises exist within a market economy. And so their fate is still determined by capitalist laws.

This can result in cooperatives having to make redundancies in order to stay afloat, or lowering workers’ wages – even though they own the business!

Ultimately, just as nationalisation must go hand-in-hand with workers’ control, workers’ control must go hand-in-hand with nationalisation.

And nor can these steps be confined to just one or two industries. Instead, such measures must be applied to all the major monopolies and banks: “the commanding heights of the economy”.

Planned economy

Linked together, this could form the foundations for a socialist planned economy. The entire economy would be democratically managed by the working class, for the working class; geared towards providing the maximum benefit for humanity, and actually meeting society’s needs.

On this basis, workers’ in obsolete, socially-unnecessary industries – such as fossil fuels or arms manufacturing – could be ensured a just transition to decent jobs in other sectors of the economy, instead of being forced into the dole queue.

Workers’ control therefore acts as a stepping stone towards such a planned economy: raising workers’ understanding of their power and essential role in production, and providing the working class with the experience of directly managing the economy in their own interests.

Again, as Trotsky explains: “Workers’ control becomes a school for the planned economy.”

In such an economy, super-profits – currently being spent on luxury yachts, being used to buy football clubs, or simply being left to sit idly in the vault – would instead belong to us, and could be put to good use.

This could mean building decent quality housing, improving public transport and making it free to use, and properly funding healthcare and education.

This is the programme that the communists fight for.

To do all of this, we need to fundamentally transform the way society is organised and run. We need a revolution.

But thankfully we – the working class – are immensely powerful. After all, without our kind permission, telephones don’t ring, lightbulbs don’t shine, and wheels grind to a halt.