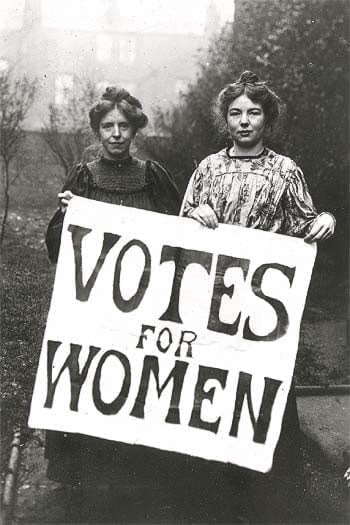

December 14th 2008 marks the 90th anniversary of a landmark election in Britain. Following the end of World War I it was the first election in which women were entitled to vote. The Representation of the People Act which became law in February 1918 had granted the right to vote on a restricted basis to women. Only women over 30 would be entitled to vote. Voting rights for all women aged over 21 did not come until ten years later, in 1928.

December 14th 2008 marks the 90th anniversary of a landmark election in Britain. Following the end of World War I it was the first election in which women were entitled to vote. The Representation of the People Act which became law in February 1918 had granted the right to vote on a restricted basis to women. Only women over 30 would be entitled to vote. Voting rights for all women aged over 21 did not come until ten years later, in 1928.

This anniversary serves to remind us that the right to vote was not granted automatically either for men or women and was the result of over 100 years of campaigning and often militant struggle. In 1832 the vote was extended but only to middle class voters. The working class still remained disenfranchised.

Means to an end

For the working class the right to vote was not an abstract right but the means to an end – to end the poverty and brutal exploitation that existed in 19th century Britain. We have just seen an historic election in the USA when for the first time millions of Afro-American voters registered to vote for the first time and queued for long hours to vote in the belief that a vote for Barrack Obama would bring about change. In the past these people would not have bothered – candidates from the Democratic and Republican Parties were seen as the same. There were scenes reminiscent of South Africa when Nelson Mandela and the African National. Congress were elected in the first apartheid-free election.

The first independent movement of the working class in Britain, the Chartists – mobilised around the Six Points of the Charter which included manhood suffrage, payment of MPs and annual parliaments. But the right to vote was seen as a means to a just reward for the working man – "bread, beef and beer". Chartism became a revolutionary movement and a National Convention was seen as the alternative to the House of Commons. Chartists joined armed demonstrations and called general strikes to support their cause, as well as collecting signatures for a mammoth petition. The ruling class were frightened of what would happen if universal suffrage was achieved. They believed that it would be the end for them – socialist revolution.

Bread, Beef and Beer

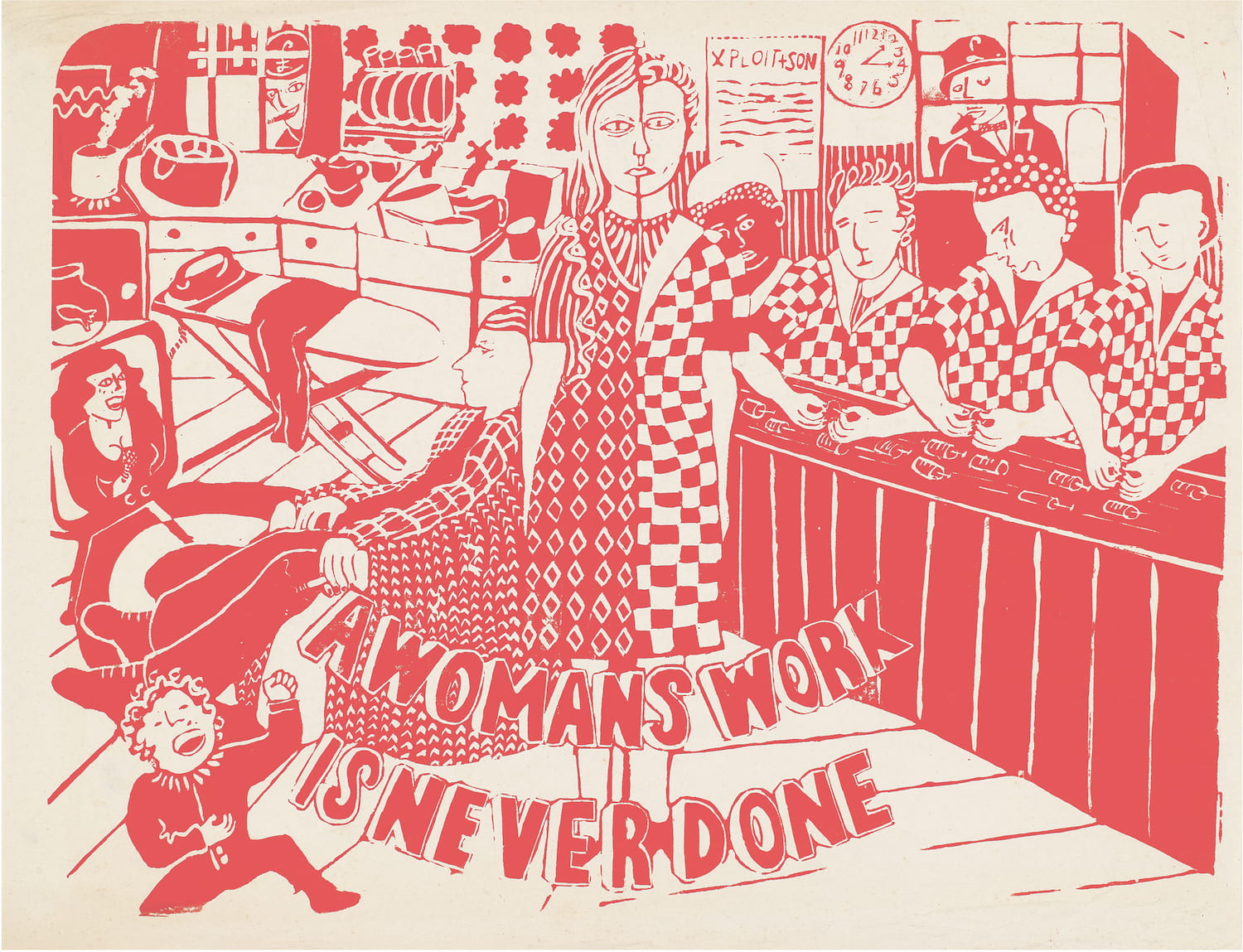

Women were involved in the political reform movement in large numbers. Within the Chartist movement they formed Female Political Unions and, although the Charter did not include the right to vote for women, they believed that if their men folk gained the vote this would improve living conditions for the working class as a whole. Female political activists were lambasted by the establishment as being a disgrace to their sex -" political harridans" they were called.

The class interests, which lay behind the right to vote were to be echoed by Selina Cooper, a supporter of the suffrages who worked in a Lancashire textile factory. She said

"Every woman in England is longing for her political freedom to make the lot of the worker pleasanter and to bring about reforms which are wanted. We do not want it as a mere plaything".

The Women’s Social and Political Union, otherwise known as the suffragettes, was founded in 1903 by Emmeline Pankhurst and her two daughters – Christobel and Sylvia.

Suffragettes

Emmeline had been a member of the Independent Labour Party but when she founded the WSPU she was having doubts about the commitment of the labour movement to votes for women. The problem was that most working class men did not have the vote either. Legislation had granted the vote to some working class men, but before the First World War only a minority of working class men had the vote. There were worries that voting qualifications for propertied women would worsen the position of the working class. Not all the trades unions were committed to women’s suffrage, especially those representing the skilled aristocracy of labour. However the TUC had backed votes for women from 1894, by 1912 the Labour Party had come out in favour and the Independent Labour Party called a demonstration in support of women’s suffrage in 1914.

With tenuous links with the labour movement the WSPU took an increasingly classless and violent approach. Many of its activists were heroines – prepared to go to prison for their cause, to go on hunger strike and endure forcible feeding. One of them – Emily Davidson – died after throwing herself under the king’s horse at a racing event. But their tactics of arson and violence shocked and in many cases alienated many people. Some suffragettes were coming around to the view that limited female suffrage would be acceptable. This alarmed the trade unions, who dubbed such proposed legislation "the ladies’ bill".

Patriotism?

When the First World War broke out, many suffragettes gave up their campaigning for the vote in the interests of "patriotism", but Sylvia Pankhurst did not. She founded the East London Federation, which continued to fight for the interests of women workers. The War brought about many changes for women. As men were sent to the front, they were employed in munitions factories and public transport, often for lower wages than had been paid to men. This became an issue for the trades union movement, and women’s membership of unions increased by 160% amongst women workers during these years. Women were also mobilised on the issues of rents and food prices at this time.

Why did

women get the vote in 1918? It has been suggested that the participation of

women in the war effort had won them the vote. Sylvia Pankhurst argued that

years of campaigning had finally won the day. The end of the War saw a

revolutionary wave across Europe, with revolutions in Russia, Germany and

Central Europe. There was to be major upheaval in the rest of Europe including

Britain.

The Representation of the People Act of 1918 enfranchised all working

class men for the first time. This prospect alarmed some of the Conservatives

who believed that giving limited franchise to women over 30 could offset the political

implications of an enfranchised working class. The extension of the franchise

in 1918 was a factor in the Labour Party becoming the second main political

party in the UK, replacing the Liberals and going on to form a minority

government in 1924, the first time that the Tory-Liberal two party system had

been challenged.

The Labour

Party continued to campaign for the right to vote to be extended to all women,

and each time they introduced a bill it would be opposed by the Tories. The

vote was finally extended to all women over 21 in 1928. It had taken over a

century to establish universal suffrage in Britain.

Revolutionary governments

in Europe introduced women’s suffrage immediately. But those who fought for the

right to vote had seen it as a means to an end, as a way of changing society. The

sense that all parties are the same and do not represent the working class has

led to apathy on a large scale. Disillusionment with New Labour has seen voter

participation fall to the lowest levels since 1918. As New Labour has embraced

the policies of the free market it has deserted its working class roots. To

make the vote effective we must ensure that the labour movement reclaims the

Party and that we have a real alternative to vote for.

See also:

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

Eleanor

Eleanor

The

The