100 years ago, in November 1918, women in the UK were allowed to stand for parliament for the first time. In December of the same year, women over thirty voted for the first time in a British general election.

These were important steps forward. However, these rights only applied to those women who met certain property qualifications. Millions of working-class women remained excluded from the vote.

It took a further ten years for the franchise to be further widened to include all women over the age of twenty-one, the same as for men.

Pressure from below

This change of voting rights for women did not materialise out of any lessening of reactionary attitudes within the British establishment. It was not granted by the sudden kindness of the government of the day. It arose from a prolonged battle lasting decades for the right to vote, which was only finally brought about due to a long campaign by militant women within the suffrage movement.

In addition, the government was being forced to extend the vote by the added pressure of international events, especially the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Great events do not take place in a vacuum – and votes for women was no exception.

The first petition demanding votes for women, signed by 1,500 women, was presented to parliament in the same year that the 1867 Representation of the People Act extended the franchise to further sections of the male working class.

This change in the franchise affected the thinking of a number of women, who began to organise with the support of the Liberal MP John Stuart Mill. He argued the case for the women’s right to vote and presented their petition to parliament.

Mill, however, approached the issue from a purely upper-class viewpoint:

“Can it be pretended that women who manage an estate or conduct a business — who pay rates and taxes, often to a large amount, and frequently from their own earnings […] are not capable of a function of which every male householder is capable?”

Mill’s argument therefore centred on so-called propertied women – members of the privileged class. They were the same as propertied men, he insisted.

This appeal ignored the vast majority of ordinary women in Britain. And it suited certain Conservative MPs of the time, who were beginning to see the potential for building up their electoral base through having propertied women voting for a party – the Conservative Party – that best protected their monied interests.

Anti-suffrage

Not all female voices in the late 19th and early 20th century, however, were in favour of a woman’s right to vote. In opposition stood anti-suffrage movements, such as that led by novelist Mary Augusta Arnold. Arnold wrote under her married name of Mrs Humphry Ward, and was president of the Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League.

These movements rested on conservative attitudes that somehow women were “too hysterical, emotional, and unintelligent” to vote. Furthermore, the anti-suffragists believed that women’s views were properly represented by their husbands and fathers, and therefore women had no need of the vote.

In addition, many working-class women simply saw no benefit in bothering to fight for the vote, especially for a parliament that had delivered nothing but pain and misery for the masses. They could see that just widening the franchise to only women with property would have little-to-no impact on their material conditions.

It should also be remembered that most of these bourgeois women would have employed working-class women as servants, cleaners, etc., and exploited them just as much as any man.

In fact, the German Marxist Clara Zetkin, writing on the movement for the vote in 1906, explained that many suffragists, such as those in Britain,

“Are not in favour of women’s rights, but of the rights of ladies; they do not fight for the political emancipation of the female sex, but for the advancement of the interests of the middle class.”

These words correctly summed up the early suffrage movement: a well meaning movement led by middle-class women fighting for the rights of other middle-class women.

Peaceful vs militant

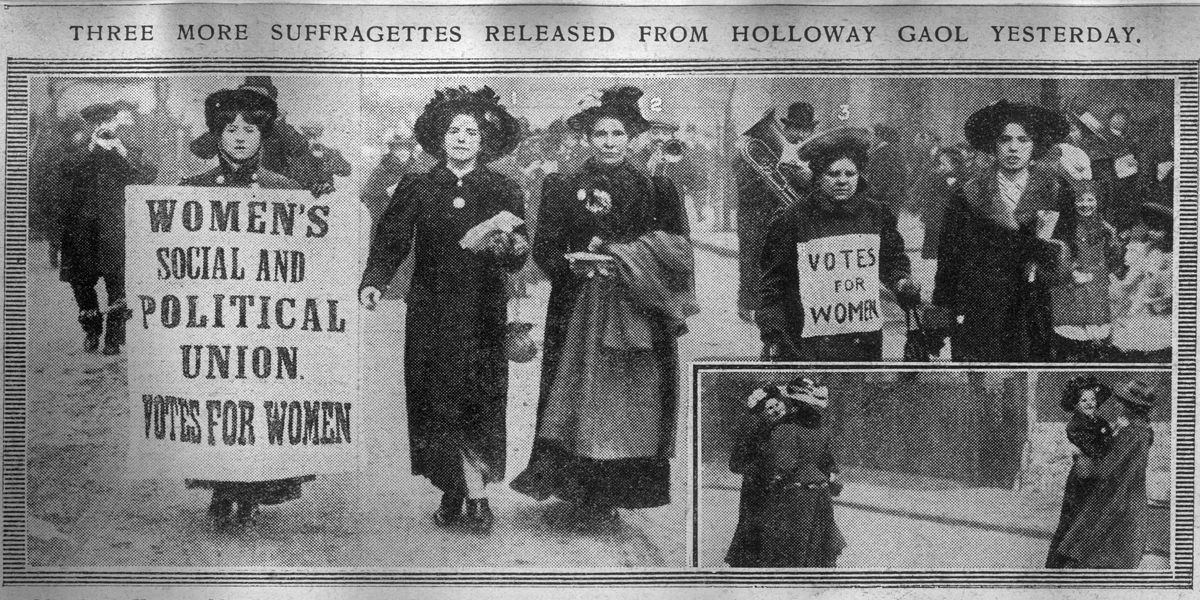

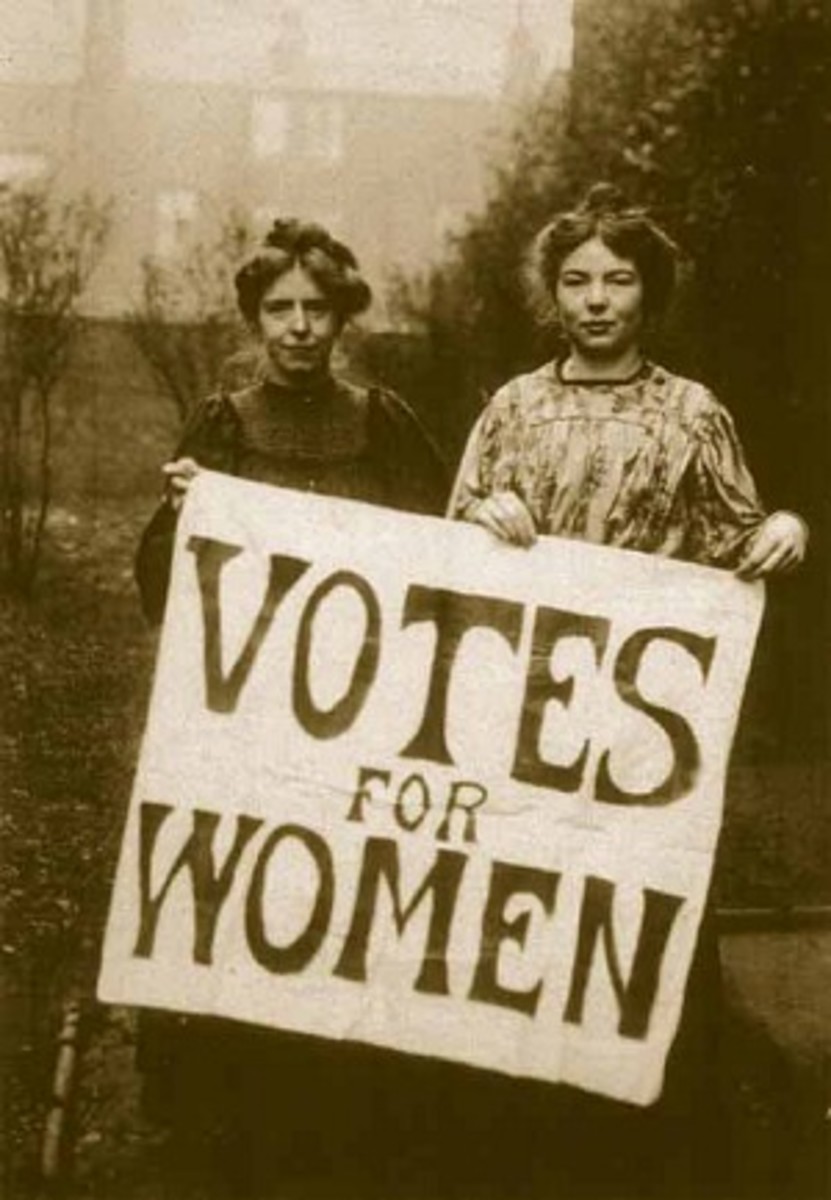

It was not until the formation of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) and later the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) – better known as the Suffragettes – that we began to see working women involved in the fight.

Before this, working-class women were either unorganised or organised in trade unions, concentrating all their energies on mainy fighting for improved working conditions – a battle that directly affected them.

The NUWSS was formed in 1897 as a federation of over 17 suffrage societies. It was led by Millicent Garrett Fawcett, who favoured peaceful methods as a way to convince the ruling class that women were not the hysterical caricatures that they believed them to be.

The suffragists hoped that through peaceful action they would convince the government that they were deserving of the vote. Fawcett famously stated that the suffragists were “like a glacier – slow moving but unstoppable”, a reference to their tactics of protesting, petitions, marches and ‘measured’ rational debate. The limits of this tactic would become obvious.

Similarly, the Suffragettes also favoured peaceful and lawful action – to begin with. Founded in 1903 by Emmeline Pankhurst, the women-only WSPU began with the intention of improving all women’s lives.

Emmeline was deeply affected by her time working in Manchester with poor and destitute women, single mothers, widows, working-class families, all struggling under the burden of poverty. Emmeline hoped to alleviate some of these problems and believed that women having the ability to vote would change things.

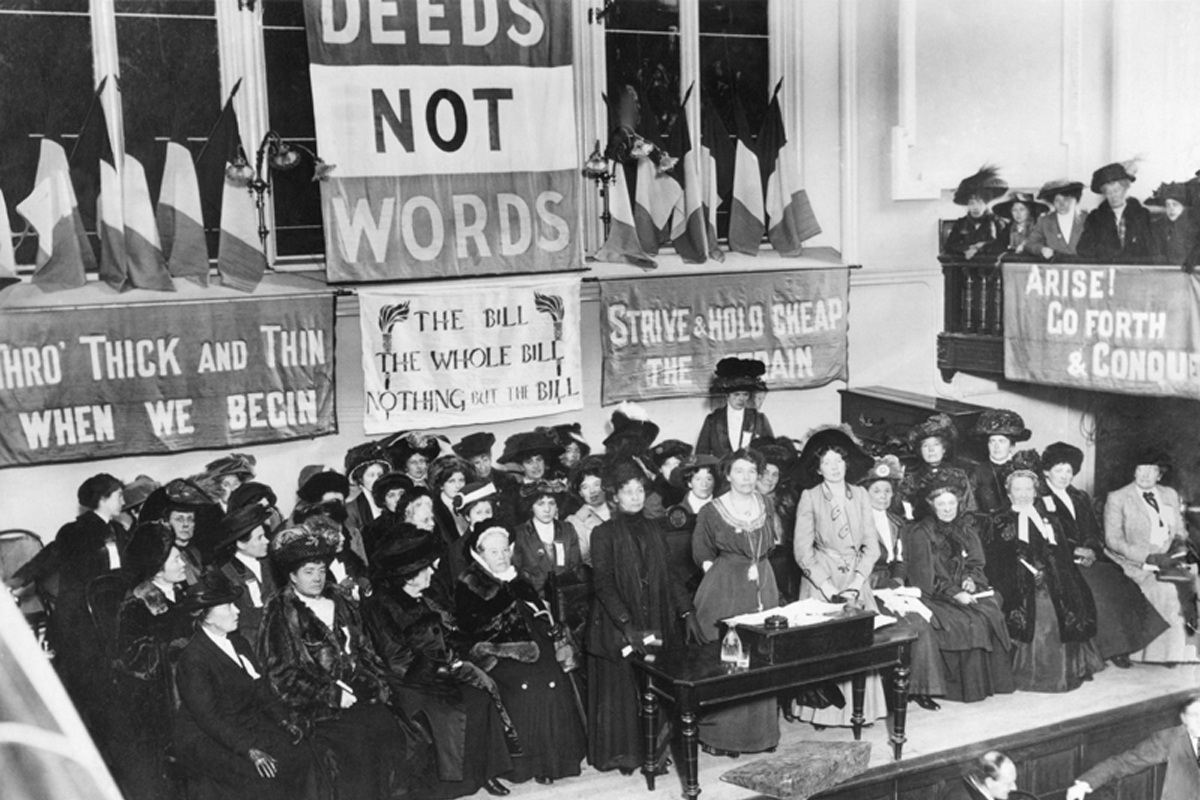

Despite beginning with similar tactics to the suffragists of Millicent Garrett Fawcett, it was not long before the Suffragettes turned towards the motto “deeds not words”: heckling MPs in meetings; dropping huge banners with the words “Votes for Women” emblazoned on them; and organising various protests – the more visible the better.

False promises

The Suffragettes, however, were far from being a democratic organisation. In fact, at the point of splitting away from Fawcett’s NUWSS, Emmeline stated,

The Suffragettes, however, were far from being a democratic organisation. In fact, at the point of splitting away from Fawcett’s NUWSS, Emmeline stated,

“The WSPU is not hampered by a complexity of rules. We have no constitution or bylaws; nothing to be amended or tinkered with or quarrelled over at a general meeting. In fact, we have no annual meeting, no business sessions, no elections of officers. The WSPU is simply a suffrage army in the field.”

The lack of internal democracy certainly impacted on their effectiveness, driving away working-class people rather than bringing them together.

Indeed this lack of democracy, together with a failure to support votes for all women, propertied or not, would lead as early as 1907 to a further split, triggered by the Labour Party’s support for universal suffrage, with the Women’s Freedom League (WFL) being formed.

The WFL was not only more militant and political than the WSPU, but it also raised issues of sexual equality and later opposed the war, unlike the WSPU leaders. They re-launched the “no taxation without representation” campaign.

The Liberal government of the time, led by Asquith, had made a series of false promises to the suffrage movement, whilst continually putting off the promise of actual women’s suffrage until “the next parliament” when, he assured women, the franchise would be widened out.

At the same time, under the charge of “obstructing the police”, in their attempts to petition Parliament, women in their hundreds were being thrown into prison, subjected to appalling conditions and refused the right to be treated as political prisoners.

But far from detering women from protesting, as the government may have hoped, women were radicalised by their time in prison. In January and February 1907 alone, over 130 women were arrested and sent to prison for the crime of “obstructing the police”.

Protests and hunger strikes

The Suffragettes held several demonstrations in Hyde Park in 1908, 1910 and 1911, aiming to attract 250,000. In reality, the demonstrations were much larger, showing increasing support for women’s suffrage. Fourteen packed meetings were held at the Royal Albert Hall. Keir Hardie, the leader of the Labour Party, was a staunch supporter.

Yet, the demonstrations and the mass meetings and rallies failed to achieve the votes for women. The government did not feel especially threatened by these protests and therefore resisted the right to vote for women.

And why did the government not feel threatened? Such protests alone could not put the government under the kind of pressure that the actions of organised workers could achieve. These protests could not mobilise the working class, nor threaten the profits of the bosses, and so could not achieve their aims. It is the working class that truly holds the power in society.

The upper- and middle-class leaders of the WSPU did not possess such strength. Their demonstrations, whilst increasing the appetite for women’s franchise, did not threaten the government as the working-class Chartist movement had done in its fight for male suffrage in the mid-1800s.

It was following a Hyde Park demonstration – after which Emmeline and others were arrested for inciting action against the government, and subjected to ill-treatment in prison – that the Suffragettes began to use the tactic of the hunger strike.

At first, the government released the weakened women early. But as soon as the scale of the hunger strikes increased, they turned to the brutal measure of force feeding prisoners. They cynically claimed that they must “preserve the dignity of the government” as well as saving lives.

This served to further radicalise women and strengthened their resolve to vigorously pursue their campaign until they had the vote. The government would later pass the so-called “Cat and Mouse” Act, whereby prisoners on hunger strike could be released and then promptly re-arrested again once they had returned to full health.

Direct action

In 1910, the Suffragettes called a halt to their campaign on account of a Conciliation Bill passing through Parliament, in which they were assured an amendment on women’s votes was to be added. However, the bill was defeated, which marked a further turning-point in the tactics of the Suffragettes.

They had attempted to change the law by peaceful means for years, but now felt betrayed by the false hopes of the Conciliation Bill. They also faced increasingly violent oppression, often sexual in nature, from the police. In these conditions, new tactics were required. Emmeline stated:

“There’s something that governments care for far more than human life, and that is the security of property, and so it is though property that we shall strike the enemy.”

Emmeline and her daughter Christabel set the WSPU the task of discrediting the government and attempting to make the situation untenable through violent action.

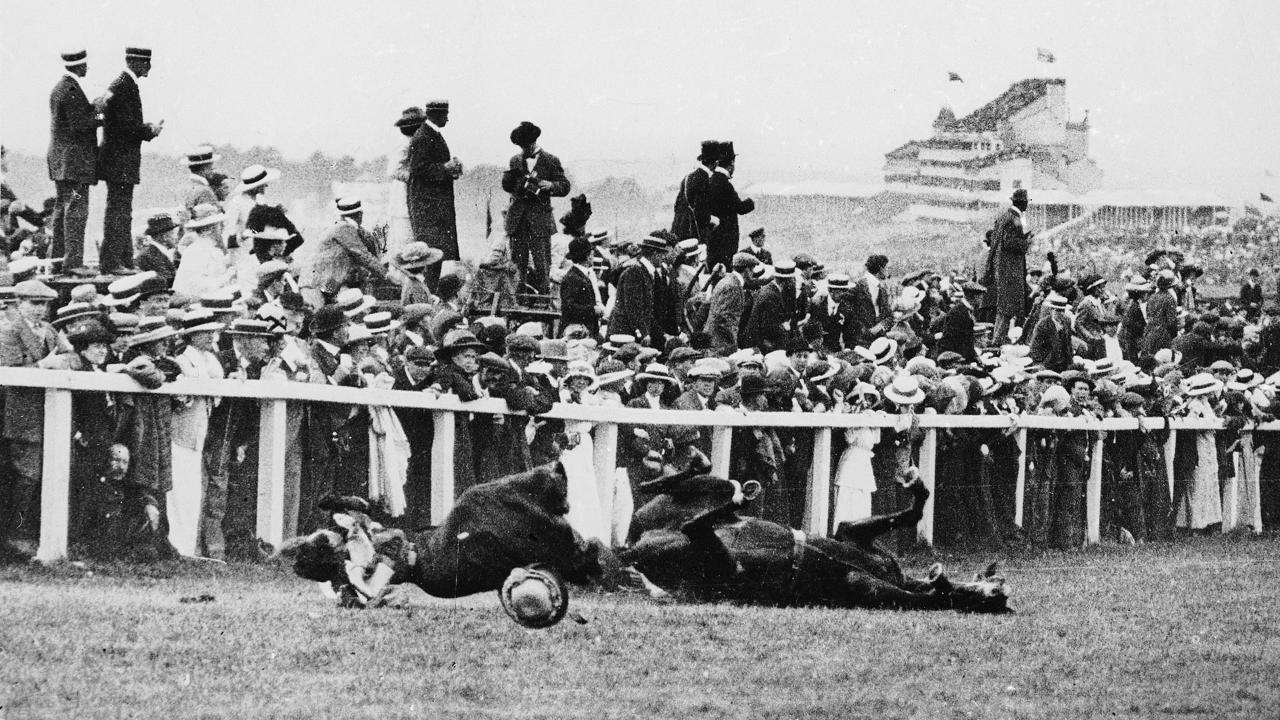

Most famously, these included the bombing of Westminster Abbey and the tragic death of Emily Davison at The Derby in 1913, when she threw herself onto the racecourse, bringing down the King’s horse. A funeral procession of 6,000 accompanied her coffin through the streets of London.

But the Suffragettes’ violent provocations, while being disruptive, affected only individual property. This could be tolerated by the establishment, which simply used these incidents to then attack the movement with impunity. Further arrests and hunger strikes followed.

Although courageous and well-intentioned, the Suffragette “outrages” reflected middle-class radicalism, drawing on the notion of “propaganda of the deed” – of creating a sensation in order to raise awareness – rather than a serious attempt to undermine the government.

Joining the struggles

The class outlook of the leaders of the Suffragettes was clearly revealed in their attitude towards the imperialist war, where they completely stopped all activity and campaigning at the outbreak of war in August 1914. Furthermore, their funds were now diverted towards assisting the war effort.

The class outlook of the leaders of the Suffragettes was clearly revealed in their attitude towards the imperialist war, where they completely stopped all activity and campaigning at the outbreak of war in August 1914. Furthermore, their funds were now diverted towards assisting the war effort.

Christabel’s first public speech was on “the German Peril”. Mrs Pankhurst devoted much of her time to army recruiting platforms. They changed the name of the paper from The Suffragette to Britannia, and shamefully campaigned with the white feather movement to pressure working-class men into fighting for Britain’s “just cause”. They also campaigned for the industrial conscription of women and the internment of all people of enemy race of whatever age.

This action led to many splits from the Suffragettes, most famously in the formation of the East London Federation of Suffragettes, founded by Amy Bull and socialist Sylvia Pankhurst.

Sylvia was another daughter of Emmeline, who strongly disagreed politically with her mother and sister Christabel. “Strongly repudiate and condemn Sylvia’s foolish and unpatriotic conduct”, telegrammed Mrs Pankhurst. “Make this public.”

Throughout the war, Sylvia and her organisation agitated for workers’ rights, linking the struggle for women’s rights to the struggle against capitalism. She encouraged strikes for equal pay and better working conditions. What was needed, she said, was “not more serious militancy by the few, but a stronger appeal to the great masses to join in the struggle”.

The East London Federation therefore concentrated, unlike the previous movements, on the working class. They linked up with socialist politicians and campaigned over issues such as widow’s pensions, nurseries for working-class families, health clinics, etc. In 1917, the Federation welcomed the Russian Revolution, having renamed itself in 1916 as the Workers’ Suffrage Federation.

War and revolution

Some argue that it was the “loyal” action of the WSPU Suffragettes during the war that finally led to the vote being granted on account of them having “proved their worth to the nation”. But this argument fails to take into account the material changes that occurred during this period.

Some argue that it was the “loyal” action of the WSPU Suffragettes during the war that finally led to the vote being granted on account of them having “proved their worth to the nation”. But this argument fails to take into account the material changes that occurred during this period.

Firstly, by 1915, it seemed inevitable that a new Conciliation Bill, with an amendment for women, would pass through parliament. This bill had come about through pressure to grant the right to vote to working-class men fighting on the front line. Consequently, when it finally passed in 1918, the Representation of the People Act enfranchised all men for the first time.

This led to a fear amongst the ruling class, however, that enfranchising so many working-class men would change the balance of forces in British politics in favour of socialism and the emerging Labour Party. They therefore hoped that this could be balanced by granting middle-class women with property over the age of thirty the vote.

Furthermore, the war had brought more women into employment than ever before. As a consequence of organising in their workplaces, trade union membership for women increased by 160%.

This threat of an organised working class was underlined by the success of the Russian Revolution of 1917, which granted women in Russia the vote immediately. This put pressure on the British government, who feared a Bolshevik revolution in Britain. And so, in an attempt to appear “democratic”, a small portion of women were duly enfranchised.

Finally, the threat of further violence after the war was ever-present from the ranks of the Suffragettes, whose leadership needed to be “bought off” by the granting of the vote to some women. It was the middle-class leadership of the Suffragettes who were enfranchised, and so the government cut the head off the movement.

Emmeline Pankhurst later, as an anti-Bolshevik, joined the Conservative Party shortly before her death in 1928. Her daughter Christabel also moved further to the right and became a religious obsessive in later years.

It was these tumultuous conditions, created by all of these material changes, that led to the winning of the vote in 1918. It was certainly not as a “reward” for “good work” during the war.

Emancipation from capitalism

Even after the right to vote was finally given to all women aged 21 and over, it was clear that the real fight had only just begun. The vote was not an end in itself but a means to an end, as Sylvia Pankhurst explained. This meant a fight – as it does today – against the whole system and the class who defend it.

Even after the right to vote was finally given to all women aged 21 and over, it was clear that the real fight had only just begun. The vote was not an end in itself but a means to an end, as Sylvia Pankhurst explained. This meant a fight – as it does today – against the whole system and the class who defend it.

Sylvia Pankhurst was correct in her attempt to fuse the women’s movement with the workers’ movement. The women’s movement is the workers’ movement. Neither men nor women will see change in society unless they unite together.

It is the working class that really holds the power in society, which can be used to overthrow capitalism. As Sylvia said, women cannot survive on “mere platitudes”, but should demand for themselves, “a full share in the benefits of civilisation and progress.”

That means the fight for a socialist society that will bring about the real emancipation of women and men. The battle for the vote was part of this struggle.