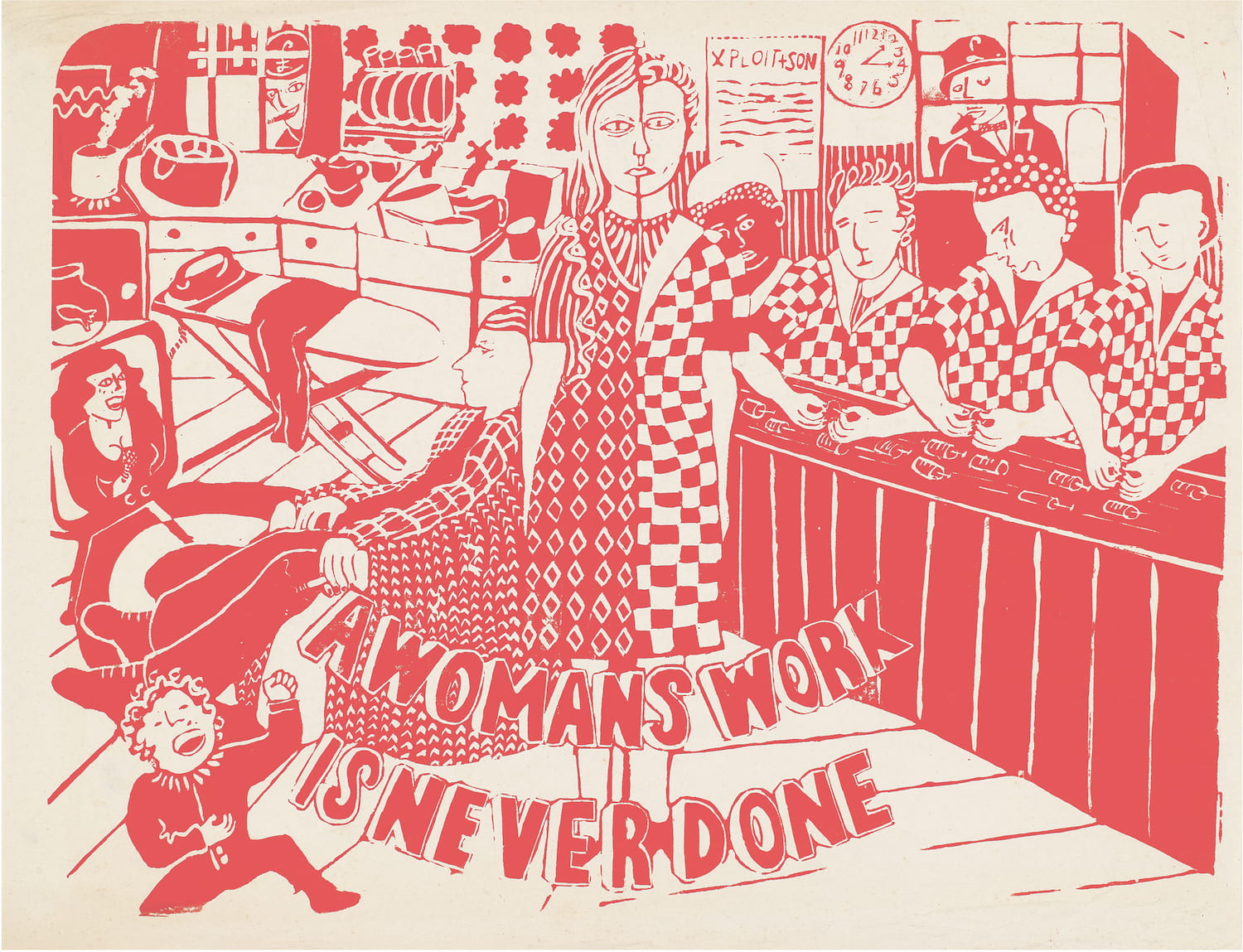

The times leading up to the Paris Commune were difficult for all

workers, but especially for women. It was typical for a woman to work 13

hours a day, six days a week. Even still, the wages she received for

that work were woefully shy of the cost of living at the time, even if

her wages were added to her husband’s. This contradiction drove many

working women to prostitution

“We have come to the supreme moment,

when we must be able to die for our Nation. No more weakness! No more

uncertainty! All women to arms! All women to duty! Versailles must be

wiped out!” These were the words of Nathalie Lemel, participant in the

Paris Commune of 1871, and member of the Union des Femmes pour la Defense de Paris et les Soins aux Blesses (The Union of Women for the Defense of Paris and Aid to the Wounded).

Such a bold statement is quite contrary to the demur and frailty that

is attributed to women of that time period. These were militant women

fighting for the gains of the working class in the Paris Commune. In

honor of International Working Women’s Day, we would like to highlight

the efforts and achievements made by the working women during the

Commune. Women like Louise Michel, Elisabeth Dmitrieff, André Léo, Anne

Jaclard, Paule Mink, and Nathalie Lemel, organized secular schools,

ambulance services, and work cooperatives, as well as taking up arms for

the revolution. The working women of the Commune fought for women’s

rights on a class basis, and defended the revolution with their very

lives.

The times leading up to the Paris Commune were difficult for all

workers, but especially for women. It was typical for a woman to work 13

hours a day, six days a week. Even still, the wages she received for

that work were woefully shy of the cost of living at the time, even if

her wages were added to her husband’s. This contradiction drove many

working women to prostitution. The Franco-Prussian war put further

strain on the French people, particularly during the months-long siege

of Paris, when they were completely blocked off from the outside. This

led to soaring inflation and to long lines to get bread that was scarce,

and often mixed with straw and paper. It was primarily the women who

had to stand in these lines and literally fight for the bread needed to

feed their families. This laid the basis for the militancy that was seen

amongst women during the Commune, who led the charge on many occasions.

After the French armies of Emperor Louis Bonaparte were defeated by

the Prussians, the Parisian workers rose up and declared a republic.

However, power fell into the hands of the right-wing representatives of

the bourgeoisie. On March 18, the reactionary leader of the new

government, Adolphe Thiers, sent troops to take cannons out of Paris in

the middle of the night. His aim was to disarm the workers and to sell

out to the Prussians. The women of the neighborhood of Montmartre awoke

and charged up the hill where they swarmed and fraternized with the

troops, placed themselves on the cannons, and stopped them from being

removed. The troops were so persuaded by the women and the people’s

militia of the National Guardsmen of Paris that they went over to the

people, arresting and firing upon their own commander.

With this, a situation of dual power developed. Thiers lost control

of Paris and had to flee with the bourgeois government to nearby

Versailles. The workers of Paris declared the Commune, the world’s first

workers’ republic. The most advanced elements in the Commune, including

hundreds of women, gathered to march to Versailles in an attempt to

stop the bloodshed and to “tell Versailles that the Assembly [the old

government] is not the law—Paris is!” But the leadership of the Commune

vacillated and the opportunity was lost. By allowing the forces of

reaction to regroup, by not decisively marching on Versailles to crush

the enemies of the revolution, the balance of forces eventually tipped

back in favor of the bourgeois and their representatives, with fatal

consequences for tens of thousands of Communards.

The beginnings of a new society

The Commune formed many clubs, which often commandeered churches to

hold their meetings. These meetings had open, heated discussions, and

used direct democracy. A main topic of discussion in the clubs was

anti-clericalism. The working women denounced the way the churches

controlled wealth, mistreated workers, controlled girls’ schools, and

invaded family privacy. It was also suggested by some that the nuns be

thrown into the Seine River, while others requested that all priests be

arrested until the end of the war.

Many of the workers in France were influenced by the proto-anarchist

Proudhon, who believed that the proper place for women was either as

“housewife or harlot,” and by no means as part of the workforce. He even

put forth a series of “equations” to illustrate that women were

physically, intellectually, and morally inferior, and should therefore

keep to child rearing and nothing else. This, along with the generally

backwards attitudes of many men at that time, including many advanced

workers, led to the French section of the First International presenting

a memorandum against women participating in the workforce. Nonetheless,

there were several women in France who belonged to the International,

and this line of thinking had nothing to do with the ideas of Marx and

Engels, its key leaders, who were doing their best to keep up with

events from London.

Louise Michel and the Montmartre Vigilance Committee

Another important group was the Montmartre Vigilance Committee, which

was divided into a men’s section and a women’s section. Louise Michel,

one of the most inspiring figures of the Commune, belonged to both. The

Vigilance Committee held workshops, recruited ambulance nurses, gave aid

to wives of soldiers, sent speakers to the clubs, and hunted draft

dodgers who refused to serve in the people’s militia. Louise Michel was

elected as its president, and served as a fighter and medical worker in

the 61st Battalion during the Commune.

Before the Commune was elected, Michel offered to go to Versailles to

shoot Thiers herself, but was dissuaded for fear of retribution.

Nevertheless, she went to Versailles just to prove she could come back

unscathed.

During the Commune, Michel sent a letter to the mayor of Montmartre

with a series of demands, including the abolishment of brothels, that

the Bell of Montmartre be melted down to make a cannon to defend the

workers’ neighborhoods, and to requisition abandoned houses and the wine

and coal within them to set up shelters and provide for the old,

infirm, and children of Montmartre. Some men in the Commune did not want

to allow prostitutes to be ambulance workers, saying “the wounded must

be tended by clean hands,” but Michel saw the necessity of involving

these women in the work of the Commune and recruited them to help in

this work. After the fall of the Commune, Thiers’ forces fought their

way through Paris and murdered tens of thousands of Communards over a

period of several weeks. Michel fought on the barricades at the cemetery

of Montmartre during the “Bloody Week,” and was subsequently arrested

and deported to New Caledonia along with Nathalie Lemel.

The Union des Femmes

Elisabeth Dmitrieff was born in Russia and co-founded the Russian

section of the First International. Active in the Narodnik movement,

Dmitrieff was sent to London to work with Marx and study the London

worker’s movement. After the declaration of the Paris Commune, the

London General Council decided to send Dmitrieff as one of two envoys to

the Commune.

After meeting with other working women active in the Commune, she saw

the need to organize the working women of Paris to defend the Commune

at the barricades, ambulance stations, and canteens, as well as to fight

for socialist measures that would emancipate working women from

exploitation. This led to the setting up of the “Women’s Union,” the Union des Femmes.

Nathalie Lemel joined the Union [4.] after its formation and, as a

book binder, had a wealth of experience in the Parisian labor movement,

in addition to being a member of the First International. The influence

of Lemel’s labor and strike experience is instantly recognizable in the

work of the Union.

The first meeting of the Union [6.] took place on April 11, after an

Appeal to the Women Citizens of Paris was put up on the walls of the

city and published in the papers. A provisional Central Committee was

appointed which included Dmitrieff and seven other working women. The Union des Femmes

was made up of working-class women and was part of the First

International. It was organized around citywide associations, with a

central committee and a paid executive committee. All positions were

democratically elected and recallable by the union members.

Each arrondissement (mayoral district of Paris) had Union

committees for recruiting militant working women, for finances, and for

summoning the members to defend the Commune at any given moment. The Union

financed itself with dues as well as money it received from the central

bodies of the Commune. After the executive committee was paid, they

used the remaining money to help support ill and/or impoverished members

of their union, as well as to buy weapons for defense of the Commune.

The Union des Femmes represented the most advanced layer of

the working women of Paris. They consistently showed their militancy and

willingness to fight to defend the gains of the Paris Commune. On May

3, a poster was put up throughout Paris calling for an armistice with

Versailles and signed by an anonymous group of “Citizens.” The Union responded days later with a militant manifesto decrying an armistice with the counterrevolution

and demanding the right of the working women of the Commune to take up

arms alongside the men in defense of the revolution, saying: “Women of

Paris will prove to France and to the world that they too, at the moment

of supreme danger—at the barricades and at the ramparts of Paris, if

the reactionary powers should force her gates—they too know how, like

their brothers, to give their blood and their life for the defense and

triumph of the Commune, that is, the People.” This manifesto flies in

the face of anyone who doubts the courage and ability of women in

revolutionary battle.

Because so many of the business owners had fled Paris, many working women found it difficult to find jobs. The Union

presented the Commission for Labor and Exchange with a request for

immediate work making uniforms for the National Guard militia, and a

long-term request to form a Federation of Women’s Associations. This

document, signed by Dmitrieff, clearly displayed the internationalist,

socialist character of the Union des Femmes while rejecting

bourgeois feminism: “An end to all competition between male and female

workers—their interests are identical and their solidarity is essential

to the final worldwide strike of labor against capital.”

The document also stated that every member was to be a member of the

First International. The Central Committee was to liaison with foreign

organizations for product exchange, and the Arrondissement Committees

would enroll women workers to keep track of occupations, as well as

women who work at home. The federation would be made up of five members

of each Arrondissement [16. italicize] Committee. On May 17, the Union

put out an appeal to working women to meet on the 18th with the

objective of setting up a Federal Chamber of Working Women. The final

drafting of the syndicate and federal chambers took place at the Hôtel

de Ville on May 21.

The Union des Femmes also fought for the working women of

the Paris Commune by demanding equal pay for women, the right to

divorce, education for girls, and much more. To help the worker

cooperatives that sprang up during the Commune compete with independent

businesses, the Union made an organizational plan for cashiers

and accountants of these cooperatives, to help them formulate price and

wage structures during the transition from capitalism to a socialist

future. They also fought to end the distinction between “legitimate” and

“illegitimate” children. A pension was enacted for wives or

“concubines” of dead National Guardsmen, as well as each of her

children—“legitimate” or not. Orphans were to receive an education at

the expense of the Commune. In short, many measures were enacted that

benefited the working women of Paris directly. On the day before

Versailles troops entered Paris to crush the Commune in blood, equal pay

for men and women workers was declared. But this advanced reform was

lost along with the Commune, and still remains unrealized in most of the

world to this day.

Bourgeois feminism

Bourgeois feminism analyzes the issue of women’s exploitation on a

gender basis, from the standpoint of the oppression of women at the

hands of men. They do not recognize that women workers are a

super-exploited layer of the working class. They applaud bourgeois women

for “breaking the glass ceiling,” or running for president, without

understanding or admitting that these women do not at all represent the

interests of working women—who make up the vast majority of women in

society.

The Union des Femmes had a very different approach. They

analyzed working women’s oppression on a socialist, working class basis.

They understood and explained that the only way to emancipate women

from their exploitative conditions was to reorganize their work and give

all workers ownership and control over the means of

production. The only way for working women to fight their exploitation

is on a class basis, inside the labor movement, and to link the

suffering of women to the suffering of the entire working class.

A U.S. labor party armed with a socialist program could fight for

legislation that would help working women and ease the burden of the

“second unpaid shift.” It would fight for universal, socialized health

care, child care, laundry services, cheap and nutritious community

restaurants, enforcement of anti-discrimination laws, equal pay for work

of equal value, and card-check legislation that would allow more

working women (and men) to organize and join labor unions. These reforms

would ease the dependence of working women on their also-exploited

husbands, giving them financial independence and the ability to escape

abusive partnerships. They would allow men and women to relate to each

other on a new basis, as workers, in solidarity, and in the best

interests of society as a whole.

As Marxists, we fight for any reforms that help working women, while

at the same time explaining that the only way to fully emancipate women

is to abolish capitalism. The achievements of the working women of the

Paris Commune cannot be overlooked when discussing women’s issues and

are an important tool in our arsenal.