For Marxists, the root cause of all forms of oppression consists in the division of society into classes. But oppression can take many forms. Alongside class oppression we find the oppression of one nation over another, racial oppression, and the oppression of women.

Marxists must fight against oppression and discrimination in all its forms, while pointing out that only a radical transformation of society and the abolition of class slavery can create the conditions for the abolition of slavery in all its manifestations and the establishment of a truly human society based upon equality, justice and freedom.

The oppression of women did not always exist. In fact, the family as we know it today has not always existed but is a transient form. Marxism explains that it arose together with class society, private property and the state. The oppression of women is only as old as the division of society into classes. Its abolition is therefore dependent on the abolition of classes, that is, on the socialist revolution.

This does not mean that the oppression of women will automatically vanish when the proletariat takes power. The psychological heritage of class barbarism will finally be overcome when the social conditions are created for the establishment of real human relations between men and women. But unless and until the proletariat overthrows capitalism and lays the conditions for the achievement of a classless society, no genuine emancipation of women is possible.

Nor does it mean that women should wait for the socialist revolution to solve their problems and in the meantime submit meekly to discrimination, humiliation and male domination. On the contrary, without the day-to -day struggle for advance under the present society, the social revolution would be unthinkable. It is precisely through the struggle for partial gains and reforms that the working class as a whole learns, develops its consciousness, acquires a sense of its own power, and raises itself to the level demanded by great historical tasks.

Many young women first become aware of the need to change the existing society through the struggle for women’s rights. They are motivated by a burning sense of injustice at the barbaric treatment of women in a society that hypocritically proclaims its adherence to democracy and justice while relegating half of humanity to a position of degrading inequality, discrimination and oppression of all kinds.

The need for revolution

There are many demands we can and must fight for right now: for the outlawing of all forms of discrimination in society and the workplace; for equal pay for work of equal value; for abortion and divorce rights; an end to discrimination against single parents; for the protection of women against male violence; action against sexual harassment, rape and domestic violence; a house and a job for everyone; free high quality child care, and so on.

All this is absolutely necessary. However, the fight for the emancipation of women can never be fully realized on the basis of a society where the immense majority are dominated, controlled and exploited by the bankers and capitalists. In order to put an end to the oppression of women, it is necessary to put an end to class oppression itself. The struggle for the emancipation of women is therefore organically linked to the struggle for socialism.

In order to bring about the socialist revolution, it is necessary to unite the working class and its organizations, cutting across all lines of language, nationality, race, religion and sex. This implies, on the one hand, that the working class must take upon itself the task of fighting against all forms of oppression and exploitation, and place itself at the head of all the oppressed layers of society, and on the other, must decisively reject all attempts to divide it—even when these attempts are made by sections of the oppressed themselves.

There is a fairly exact parallel between the Marxist position on women and the Marxist position on the national question. We have an obligation to fight against all forms of national oppression. But does this mean that we support nationalism? The answer is no. Marxism is internationalism. Our aim is not to erect new frontiers but to dissolve all frontiers in a socialist federation of the world.

The bourgeois and petty bourgeois nationalists play a pernicious role in dividing the working class on nationalist lines, playing on the understandable feelings of resentment caused by long years of discrimination and oppression at the hands of the oppressor nationality. Lenin and the Russian Marxists waged an implacable struggle on the one hand against all forms of national oppression, but also on the other hand against the attempts of bourgeois and petit bourgeois nationalists to make use of the national question for demagogic purposes. They insisted on the need to unite the working class of all nationalities in the struggle against landlordism and capitalism as the only real guarantee for a lasting solution to the national question in a socialist federation.

In other words, the Marxists approach the national question exclusively from a class point of view. It is the same with the attitude of Marxists towards the oppression of women. While fighting against all forms of discrimination and oppression, we must decisively reject any attempt to present the problem as a conflict between men and women, and not as a class question. Any division between different groups of workers: women against men, blacks against whites, Catholics against Protestants, Sunni against Shia, can only harm the cause of the working class and help to perpetuate class slavery.

Women and Revolution

Actually, the whole history of the movement shows that the class question is primary, and that there has always been a sharp struggle between the women of the oppressed classes, who stood for revolutionary change, and the well-to-do women “progressives” who merely used the question of the oppression of women for their own selfish purposes. At every stage, this class difference has manifested itself, and moreover in the sharpest forms. A couple of examples will suffice to illustrate this point.

As early as the 17th century, women began to advance the demand for their social and political emancipation. The English Revolution saw an increasing participation of women in the fight against the monarchy and for democracy and equal rights. In 1649 we had the Women’s Petition of the City of London which states that: “Since we are assured of our creation in the image of God, and of an interest in Christ equal unto men, as also of a proportional share in the freedoms of this Commonwealth, we cannot but wonder and grieve that we should appear so despicable in your eyes, as to be thought unworthy to petition or represent our grievances to this honourable House.

“Have we not an equal interest with the men of this Nation, in those liberties and securities contained in the Petition of Right, and the other good laws of the land?” (From J. O’Faolain and L Martines, Not in God’s Image, pp. 266-7.)

Women were active in radical groups and religious sects on the left of the revolutionary movement which held that women could be preachers and ministers. Mary Cary, for example, was associated with the radical “Fifth Monarchy” movement. In The New Jerusalem’s Glory she wrote:

“And if there be very few men that are thus furnished with the gift of the Spirit; how few are the women! Not but that there are many godly women, many who have indeed received the Spirit: but in how small a measure is it? how weak are they? and how unable to prophesie? for it is that that I am speaking of, which this text says they shall do; which yet we see not fulfilled… But the time is coming when this promise shall be fulfilled, and the Saints shall be abundantly filled with the spirit; and not only men, but women shall prophesie; not only aged men, but young men; not only superiours, but inferiours; not only those that have University learning, but those that have it not; even servants and handmaids.”

Women in the French Revolution

By the time of the French Revolution, the situation was much changed. Class relations had become clearer, sharper and so had consciousness. The Revolution no longer had any need to clothe itself in Biblical garb. Instead, it spoke in the language of Reason and the Rights of Man. But what of the rights of Woman?

The French Revolution can only be understood from a class point of view. The different parties, clubs, tendencies and individuals, which appear in bewildering array, rising and falling like waves on a troubled sea, were merely the expression of different classes struggling for mastery of the situation, and the general law of every revolution that the more radical always tends to displace the more moderate trend, until the revolutionary momentum has exhausted itself and the film of revolution begins to unwind and go into reverse. This is the inevitable destiny of every bourgeois revolution, where the impulse that comes from the masses eventually founders upon the contradiction between their illusions and the real class content of the movement.

The class divisions within the revolutionary movement were manifested from the very beginning. The Girondins represented the bourgeois trend which wanted to halt the revolution half-way and do a deal with the king to establish a Constitutional Monarchy. This would have been fatal to the Revolution, which only acquired the necessary sweep because the masses erupted onto the scene and began to settle accounts with the reaction in revolutionary plebeian style. It was the eruption of the masses—so brilliantly described in Kropotkin’s book on the subject—that guaranteed the victory of the French Revolution and so thoroughly dissolved the old order.

It is not generally realized that women played a leading role in both the French and the Russian Revolutions. But we are not referring here to the educated middle-class feminists, who did emerge in the course of the revolution, but to ordinary working class and plebeian women, who rose in revolt against the oppression of their class. The plebeian and semi-proletarian women of Paris who started the French Revolution in 1789 rose up on the question of bread, not initially on the question of the oppression of the female gender, although naturally this emerged in the course of the Revolution itself.

“Excluded from the vote, and from the majority of popular societies, women could, and did, play a very significant role in insurrections, particularly those of October 1789, 10 August 1792, and, most prominently, the risings of the Spring of 1795 (known as the risings of Germinal and Prairial Year 3 according to the names of the months of the Revolutionary Calendar introduced in 1792). Women, even the most radical of them, rarely demanded the vote, conditioned as they had been by the eighteenth-century gendered distinction which placed men in the ‘public sphere’ and women in the ‘private sphere’. They did set up women’s popular societies, the most famous of which was the Society of Revolutionary-Republican Citizens; but this club would only last from May to October 1793. Nonetheless, as historians like Dominique Godineau and Darlene Levy point out, this does not mean that women did not share the men’s political and economic programme. Women supported, even encouraged, men to action. They sat in the galleries of the popular societies; they created their own political space outside bread-shops, in the market-place, in the streets.” (The French Revolution, 1787-1799. The People and the French Revolution, by Professor Gwynne Lewis.)

A revolution stirs up society to the depths, releasing feelings and aspirations long pent up within the masses and every oppressed layer. The demand for the emancipation of women therefore assumed a burning significance. But this demand was understood differently by different tendencies which ultimately rested on different class interests. It was no accident that the women of the poor Parisian proletariat and semi-proletariat led the way. They were the most oppressed layer of society, those who had to bear the brunt of the suffering of the masses. Also, they had no experience of political struggle and organizations, and came onto the scene unencumbered by prejudices. By contrast, the men were more cautious, more hesitant, more “legalistic”. This contrast has been seen many times since. In numerous strikes, where women have been involved, they have consistently shown far greater militancy, élan and courage than the men. Significantly, it was on the class issues—the question of bread—that these women began to move. The same was true over 100 years later in Petrograd.

At every key turning-point of the French Revolution—at least in the early stages—the women of the lower classes gave a lead. In October 1789, while the gentlemen of the Constituent Assembly talked endlessly about reform and constitutions, the poor women of Paris—the fish-wives, washerwomen, seamstresses, shop girls, servants and workers’ wives, rose up spontaneously. These female sans culottes organised a demonstration and marched to the Paris Town Hall demanding cheaper bread. They shamed the men to march on Versailles and bring back the king and queen (they made no distinction between the two—if anything the “Austrian woman” was more hated than her husband) under virtual house-arrest. The scene is well described by George Rudé:

“By now, the women had begun to take a hand. The bread crisis was peculiarly their own and, from this time on, it was they rather than the men that played the leading role in the movement. On 16 September Hardy recorded that women had stopped five carts laden with grain at Chaillot and brought them to the Hôtel de Ville in Paris. On the 17th, at midday, the Hôtel de Ville was besieged by angry women complaining about the conduct of the bakers; they were received by Bailly and the Municipal Council. ‘Ces femmes [wrote Hardy] disaient hautement que les hommes n’y entendaient rien et qu’elles voulaient se mêler des affaires’ [‘These women loudly proclaimed that the men could understand nothing and that they were going to sort things out themselves.’] The next day the Hôtel de Ville was again besieged, and promises were made. The same evening Hardy saw women hold up a cartload of grain in the Place des Trois Maries and escort it to the local District headquarters. This movement was to continue up to and beyond the political demonstration of 5 October.” (George Rudé, The Crowd in the French Revolution, p. 69.)

And again:

“From these beginnings the women now converged on the Hôtel de Ville. Their first object was bread, the second probably arms and ammunition for their men. A merchant draper, passing by the old market hall at half past eight, saw groups of women stopping strangers in the streets and compelling them to go with them to the Town Hall, ‘où l’on devait aller pour se faire donner du pain’[‘ where one should go to get some bread ’]. The guards were disarmed and their arms handed to the men who followed behind the women and urged them on. Another eyewitness, a cashier in the Hôtel de Ville, described how, about half past nine, large numbers of women, with men amongst them, rushed up the stairs and broke into all the offices of the building. One witness said they bore sticks and pikes, while another insisted they were armed with axes, crowbars, bludgeons, and muskets. A cashier, who had the temerity to remonstrate with the invaders, was told ‘qu’ils étaient les maîtres et les maîtresses de l’Hôtel de Ville’. In their search for arms and powder the demonstrators tore up documents and ledgers, and a wad of a hundred 1,000-livres notes of the Caisse des Comptes disappeared from a cabinet. But their object was neither money nor loot: the City Treasurer later told the police that something over 3.5 million livres in cash and notes were left untouched; and the missing banknotes were returned intact a few weeks later. Having sounded the tocsin from the steeple, the demonstrators retired to the Place de Grève outside at about 11 o’clock.

“It was at this stage that Maillard and his volontaires arrived on the scene. According to his account, the women were threatening the lives of Bailly and Lafayette. Whether it was to avert such a disaster or merely to promote the political aims of the ‘patriots’, Maillard let himself be persuaded to lead them on the twelve-miles march to Versailles to petition the king and the Assembly to provide bread for Paris. As they set out, in the early afternoon, they removed the cannon from the Châtelet and [wrote Hardy] compelled every sort and condition of woman that they met—‘même des femmes à chapeau’—to join them.” (George Rudé, The Crowd in the French Revolution, pp. 74-5)

Here we see perfectly the way in which the working class women of Paris understood the struggle. Frustrated and impatient with the inaction of their menfolk, they launched themselves into the struggle with tremendous élan that swept all before it. But at no time did they see the struggle as one of “women against men”, but a struggle of the whole class of poor and exploited people against the rich oppressors. Beginning with economic demands (“bread”), they marched to the town hall, and in the process – as we have already seen – another demand emerged almost of its own accord: the demand of arms.. The objective was to shame the men into action—and in this the women of Paris succeeded brilliantly and saved the Revolution.

The emergence of the masses on the scene of politics is the first and most fundamental element in every revolution. This is particularly true of the women. In the French Revolution, the women were by no means content to leave politics to the men. In Paris we saw the establishment of the pro-Jacobin Citoyennes Républicaines Révolutionaires (Revolutionary Republican Women Citizens) who wore a uniform of red and white striped pantaloons and red liberty bonnets and carried arms on their demonstrations. They demanded votes for women and the right of women to hold the highest civilian and military posts in the Republic—that is, the right of women to full political equality with men, and the right to fight and die for the cause of the Revolution.

However, the Revolution itself was characterised by a constant struggle of parties and tendencies in which the more radical tendency constantly overtook and replaced the more moderate trends, until the Revolution had finally exhausted its potential and began to unwind in a downward spiral that led to Bonapartism and Waterloo. This party strife at bottom reflected the struggle between different classes. The Girondin faction represented that section of the bourgeoisie which feared the masses and was striving for a deal with the king. These class antagonisms—which assumed a particularly bitter form in the French Revolution—also affected the woman question in a fundamental way.

The Girondin women activists—some of whom held quite advanced positions on the formal question of women’s rights—posed the question in a different way to the sans culottes women—sarcastically baptized as the tricoteuses by hostile historians because of the habit of doing their knitting while aristocratic heads fell into the basket. The women of the poor classes of Paris were undoubtedly motivated by a strong revolutionary spirit, class consciousness and an undying hatred of the rich. The Girondin women, coming from privileged middle class and bourgeois families, did not have the same immediate interests as the women of the poor Paris districts.

The Girondins passed a law on divorce which was undoubtedly an advance for women. But the Girondin women laid heavy stress on women’s property rights. At the time of the French Revolution, such a demand was by no means a burning issue for the majority of women, for the simple reason that neither they nor their husbands possessed any property. The women sans culottes who had played such an outstanding role in the Revolution were opposed to the “sacred right to property” because they understood the revolution from their own class standpoint.

Hostile to the well-to-do bourgeois, even when they wore the red bonnet of revolution, they instinctively strove for a Republic in which all men and women would be truly equal—not just equal before the Law—that is, they strove for a classless society, a world without rich and poor. We now know that this was an impossible aim at the time. The productive forces which are the material basis for socialism had not yet achieved a sufficient level of development to permit this. The class nature of the French Revolution was bourgeois of necessity. But this was by no means clear to the masses who so enthusiastically rallied to the Revolution, and who sealed its victory in their own blood. They were not fighting to hand power to the bourgeois—whether men or women, but to secure justice for their class.

Appeals to unite all women, irrespective of social class, got no echo at all among the mass of working class women who fought alongside their men folk to win a more just society.

Class divisions among the Suffragettes

The early years of the rise of the Labour Movement in Britain were also a period of intense agitation among the working class and also among women. The New Trade Unionism was born at the end of the 19th century in a series of militant strikes, which aroused the unorganized workers, sections never previously involved. Some of them involved working class women, such as the famous match girls’ strike. Marx’s daughter Eleanor played a very active role in this and other strikes at the time.

Among middle-class women, there was a growing agitation for the right to vote. However, the middle-class suffragettes were only interested in obtaining formal equality—and would have been quite contented to get votes for women property owners—that is, for women of their own class. Let us remember that at the time, many men did not have the vote. However, events soon demonstrated the reactionary nature of bourgeois feminism, which demonstrated its hostility to the cause of the working people—whether men or women.

As Jen Pickard correctly points out in her article on Sylvia Pankhurst: “The names of the Pankhurst family are synonymous with the struggle to win the vote for women, but what distinguished Sylvia Pankhurst’s approach from that of her mother Emmeline and her sister Christabel were class issues. It resulted in the 1920s, after nearly twenty years of struggle, with Emmeline standing as Tory Parliamentary candidate and Sylvia becoming a founder member of the British Communist Party.”

The Women’s Social and Political Union was set up in 1903 as a result of the dithering of the Independent Labour Party on the issue of votes for women. The WSPU grew rapidly and by 1907 had 3,000 branches, drawing in teachers, shopgirls, clerks, dressmakers and textile workers. Their newspaper Votes for Women sold 40,000 copies a week. They were able to fill the Albert Hall and organise a demonstration of 250,000 in Hyde Park.

In 1911, at the same time that the Liberal government of Asquith was promising Home Rule for Ireland, it also held out the prospect of votes for (propertied) women. But the Liberals betrayed both promises. When the suffragettes resorted to direct action for their cause, they were met by the most brutal repression: beatings, arrest, and the brutal torture of force-feeding. This campaign was mainly organised by middle-class women. But the tactic of breaking windows, advocated by the bourgeois wing of the suffragettes, led nowhere. The ruling class remained implacably opposed to votes for women.

The real way forward for the movement for women’s rights would have been to forge links with the workers’ movement, which at that time was involved in a bitter struggle with the capitalist class. This was a time of rising class struggle in Britain, with mass strikes of the dockers and transport workers. The “Liberal” Asquith sent the troops to break a miners’ strike in South Wales. One section of the women’s movement attempted to do this with some success. Sylvia Pankhurst chose to adopt the methods of agitation and propaganda among working class women in London’s East End.

In Bermondsey, in South London, striking women from a food factory were joined by 15,000 others from local factories and workshops at a mass meeting in Southwark Park. They demanded an increase in wages—and the vote. This was the way forward: to use the weapon of the class struggle to link the fight for economic demands to political demands, especially the demand for votes for women.

The different class approach resulted in a split in the suffragette movement on class lines—and also a split in the Pankhurst family. In January 1914, a few months before the War, Sylvia was summoned to Paris for a meeting with her mother, Emmeline and sister, Christabel. Sitting in comfortable exile in Paris, Christabel was a picture of health, while Sylvia was worn out by prison and hunger strikes. In stark contrast to the class position advocated by Sylvia Pankhurst, her sister Christabel stressed the independence of the WSPU from all men’s parties Christabel demanded the exclusion of the East London Federation from the WSPU. That is to say, she demanded the expulsion of the working class women from the suffragette movement.

This middle class snob argued that the East London Federation had a democratic constitution and relied too heavily on working class women. It seems that their mother attempted to compromise, but Christabel was adamant, demanding a “clean cut”. Thus, in January 1914, the East London Federation was forced to break away from the WSPU and form a separate organisation—the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELFS). This illustrates perfectly the attitude of middle-class feminism towards the working class. Jen Pickard comments: “This split in the WSPU reflected a general polarization taking place in British society. Between 1911 and 1914 every key section of workers (dockers, transport workers, railway workers, engineers) were involved in strikes. Even amongst the members of the WSPU, who were imprisoned and force-fed, it was working-class women who suffered the worst conditions and treatment.”

Here again, the class question was fundamental. The split in the suffragette movement shows the real attitude of the bourgeois feminists to working class women, socialism and the labour movement. Here we can see where the idea of “men against women” can lead. Just a few months after the split, in 1914, the First World War cut across the development of the class struggle in Britain. The Suffragette “rebels” Emmeline and Christabel were soon transformed into the most rabid social chauvinists. The name of the WSPU paper was changed fromVotes to Women to Britannia. Its new motto was “King, Country, Freedom”.

This was an abject and shameless betrayal of the cause of women. It exposed the real class nature of bourgeois feminism, and the gulf that separates it from the working class and socialism. For all their verbal radicalism and demagogy, in the last analysis, they were prepared to unite with the men of their own class—the ruling class—against the men and women of the proletariat: the ones that had to do all the fighting, dying and suffering while they waved the flag from the comfort and safety of their middle class and bourgeois homes. It is always the same story.

Sylvia Pankhurst, to her credit, opposed the war—although from a confused pacifist standpoint—and waged a campaign in the factories to get equal pay for the women who had been drafted into the arms and engineering industry to replace men at the front. She published a paper called The Workers’Dreadnaught and later joined the Communist Party, where she held an ultra left position. Her understanding of Marxism was very limited, but at least she attempted to adopt a class position. In 1918, British women over thirty got the right to vote. This was not the result of the tactics of the suffragettes, but a by-product of the Russian Revolution and the revolutionary ferment that followed the First World War which shook the British ruling class and compelled them to make concessions. Here again, reform was shown to be only a byproduct of revolution.

Women in the Russian Revolution

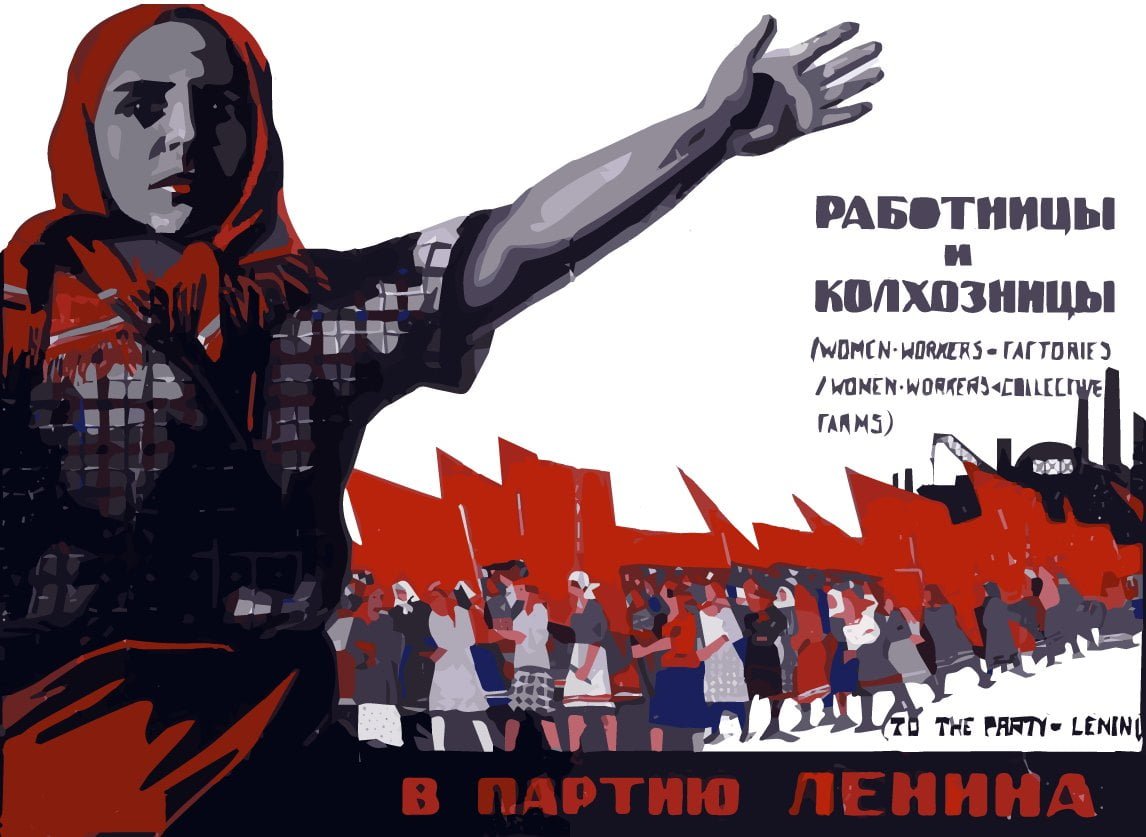

The role of working class women was again shown in Russia in February 1917. The tsar was overthrown by a revolution that began on International Women’s Day, when the women workers of Petrograd decided to strike and demonstrate despite the advice of the local Bolsheviks who feared there would be a massacre. Guided by their proletarian class instincts, they swept aside all objections and began the revolution. Women like Alexandra Kollontai played a leading role in the Bolshevik Revolution.

The October Revolution gave women rights they had never had—far greater rights than in any country in the world.

The Bolsheviks stood for liberation of women and transformation of the family. The age-old patriarchal regime had existed in villages from time immemorial, and servitude and oppression was the only life peasant women knew. Before the Revolution it was legal for a husband to beat his wife. The Bolsheviks gave women an equal legal status with men’s through the Code on Marriage, the Family, and Guardianship ratified in October 1918. Children born outside wedlock were given the same rights as those born in married families.

Divorce was made available on demand and abortion was legalised. The principle “Equal pay for equal work” was enshrined in law. Bolshevik women’s detachments spread the news of the revolution among women, set up political education and literacy classes for working-class and peasant women and fought prostitution.

During the bloody Civil War following the October Revolution, large numbers of women volunteered for the Red Army, although they were not required to do so. An estimated 50,000 to 70,000 women had joined the Red Army by 1920. That alone indicates the degree of support the Bolsheviks had gained among women.

Lenin, who attached great importance to the emancipation of women, stressed the need to relieve women from housework so they could participate more fully in the running of society. However, the Bolsheviks’ ability to solve the material problems of life was severely limited by the extremely low level of development of the productive forces. As Marx predicted: “In any society where want is general all the old crap revives.”

The real emancipation of women is possible only when the world working class as a whole emancipates itself. Socialism will permit the free development of the human personality and the establishment of genuinely human relationships between women and men, free of brutal external pressures, whether social, economic or religious. However, such a society presupposes a level of economic and cultural development that is on a higher level than the most developed capitalist nations.

In Russia in October 1917, such a basis did not exist, given the prevailing backwardness. Therefore, despite the enormous advances made possible by the Revolution, the position of women in Russia was thrown back, first by Stalinism, and even more so by the re-establishment of capitalism. The position of women in Russia and Eastern Europe is now worse than ever. This should surprise no one. On the basis of capitalism, no way forward is possible in Russia or anywhere else.

We shall see many more examples like Russia 1917 in the future. Women will play an essential role in the overthrow of capitalism and the building of socialism. But here again it is above all a question of working class women, fighting for their own emancipation—and that of the whole class. Working class women and men develop class consciousness and confidence through participation in the class struggle. In the process of fighting to transform society, men and women will also transform themselves. We can see how in every strike, the workers raise themselves to new heights, casting aside the old servile mentality and displaying an assertiveness and a creativity they never knew they possessed. How much more true will this be in the case of a revolution!

This is the only way to achieve genuine liberation—not only of women, but of all women and men. Indeed, one thing is not possible without the other. What we are striving for is the liberation, not of this group or that, but of humanity itself. This does not at all signify that women must set aside the struggle for immediate improvements. We must fight for any measure, no matter how small, that serves to improve the position of women and combat discrimination and prejudice of any kind. The labor movement must put itself at the forefront of this struggle.

The emancipation of women and socialism

The bourgeois revolutions of the past proclaimed the “rights of man” yet in practice never achieved the equality of woman. In fact, the advance of women under capitalism has been partly a byproduct of the class struggle and in part a result of the changed role of women in production. Certain political rights have been won in the advanced capitalist countries (a minority of the world), but genuine emancipation has not been achieved and can never be achieved on the basis of capitalism.

As early as 1848, Marx and Engels raised the demand for the abolition of the bourgeois family. However, they understood that the family cannot be abolished at a single stroke. This demand cannot be achieved unless there is a material basis for it. It can only be achieved by the overthrow of capitalism and the establishment of a new society based upon a harmonious and democratic plan of production, with the involvement of the whole of society in the common tasks of administration.

Once the productive forces are freed from the straitjacket of private property and the nation state, it will be possible rapidly to reach an undreamed-of level of economic wellbeing. The old mentality of fear, greed, envy and covetousness will disappear to the degree that the material conditions that give rise to it are removed.

The road will be open for a radical transformation of the conditions of life, and thus a transformation of the relations between men and women, and of their entire way of thinking and acting. Without such a giant leap, all talk of changing people’s character and psychology will be just so much clap-trap and deception. Social being determines consciousness.

The barbarism of class society, with its emphasis on selfishness, egotism and indifference to human suffering, is a remnant of slavery. The working class itself is not immune to the pressures of bourgeois society, its so-called morality, its hypocrisy and general rottenness. Backward attitudes to women can be found in the ranks of the labour movement and this poison must be combated tooth and nail.

We stand for a new society based upon complete equality between men and women, and while it will never be possible to create this new society amidst conditions of capitalist barbarism, we must at least strive for a genuinely proletarian morality and strive to purge the movement of backward attitudes that hinder the unity of men and women workers.

On the one hand, it is necessary to understand that under capitalism, any improvements will possess a partial, distorted and unstable character, and will be constantly threatened by the crisis of the system and the general deterioration of condition and social, moral and cultural decay. On the other hand, it is necessary to link the struggle against the oppression of women firmly with the struggle of the working class against capitalism. That is the only possible road to victory.

The psychological scars of the old society with its selfish calculation, greed and egotism will not disappear overnight, even after the overthrow of capitalism. A period of time must inevitably elapse before all the old filth finally disappears. But from the very beginning, relations between men and women will begin to improve. The terrible economic pressures that blight lives and distort all human relations will be abolished almost immediately with the introduction of decent jobs, housing and education for all.

A democratic socialist plan of production will create the conditions for everyone to participate in the running of society. This will, among other things, abolish the old introverted family, and the atomized individual, and create the conditions for the creation of an entirely different psychology, rooted in the new, free and human relations.

The elimination of class society—and eventually of the slave mentality that flows from the dirt of class society—will lead to the creation of a new man and a new woman: free human beings, capable of living together in harmony, as truly liberated persons, free of the old possessive slave psychology. Having freed men and women from the humiliating pursuit of material things, which distorts and degrades human life, it will be possible for the first time for people to relate to each other as humans. Freed from any external coercion, egotistical calculation or humiliating dependence, the relationship between men and women will be free to develop and flourish on the basis of genuine equality.