A new exhibition has opened at the Tate Britain in London, showcasing the paintings and prints of William Blake. Aside from being an artistic genius, Blake was a political radical whose art was directly inspired by the horrors of burgeoning English capitalism, and the revolutionary events sweeping Europe in the 18th Century.

The Great French Revolution of 1789 had a tremendous impact throughout the world, and its influence was not limited to politics. Artists and intellectuals across Europe were inspired by this heroic struggle against the stultifying dictatorship of crown and church.

One of England’s finest artists, William Blake, was just 32 when the revolution broke out. Along with his contemporaries, William Wordsworth and William Godwin, he was overjoyed when he heard the news and proudly strode around the streets of London wearing the bonne rouge (red cap) of Liberty in solidarity with the revolution.

In his epic poem, The French Revolution (1791), Blake celebrated the storming of the Bastille and heaped scorn on the decrepit feudal order, portraying the sickness of the Bourbon dynasty from the perspective of an ill and aged king, who laments: “From my window I see the old mountains of France, like aged men, fading away.”

Blake already had a reputation as a staunch republican and political radical before 1789. His home was used as a meeting place for such dissidents as Joseph Priestley, Richard Price, John Henry Fuseli, Mary Wollstonecraft and Thomas Paine.

The horrors of capitalism

As a young man, Blake bore witness to the horrors of English capitalism as it roared onto the scene, “dripping blood and dirt from every pore”. The scourges of poverty, disease and child labour were rampant. Blake was repulsed by these deprivations, in addition to the endless, bloody military adventures waged by the ruling class. Blake’s sense of indignance is captured in the marvellous, agitational poem, ‘London’:

“I wander thro’ each charter’d street Near where the charter’d Thames does flow, And mark in every face I meet Marks of weakness, marks of woe. In every cry of every Man, In every Infant’s cry of fear, In every voice, in every ban, The mind-forg’d manacles I hear: How the Chimney-sweeper’s cry Every black’ning Church appalls, And the hapless Soldier’s sigh Runs in blood down Palace walls.”

Though deeply religious, Blake despised the hypocritical religious establishment, and his revolutionary philosophy drew on the most radical elements of the English Revolution: the Diggers and the Levellers. Blake’s highly original style imbued religious and mythological symbolism with political meaning, counterposing the squalor and injustice inflicted by the Industrial Revolution with an idealised Country of God, which he believed could only be accomplished through the revolutionary transformation of society.

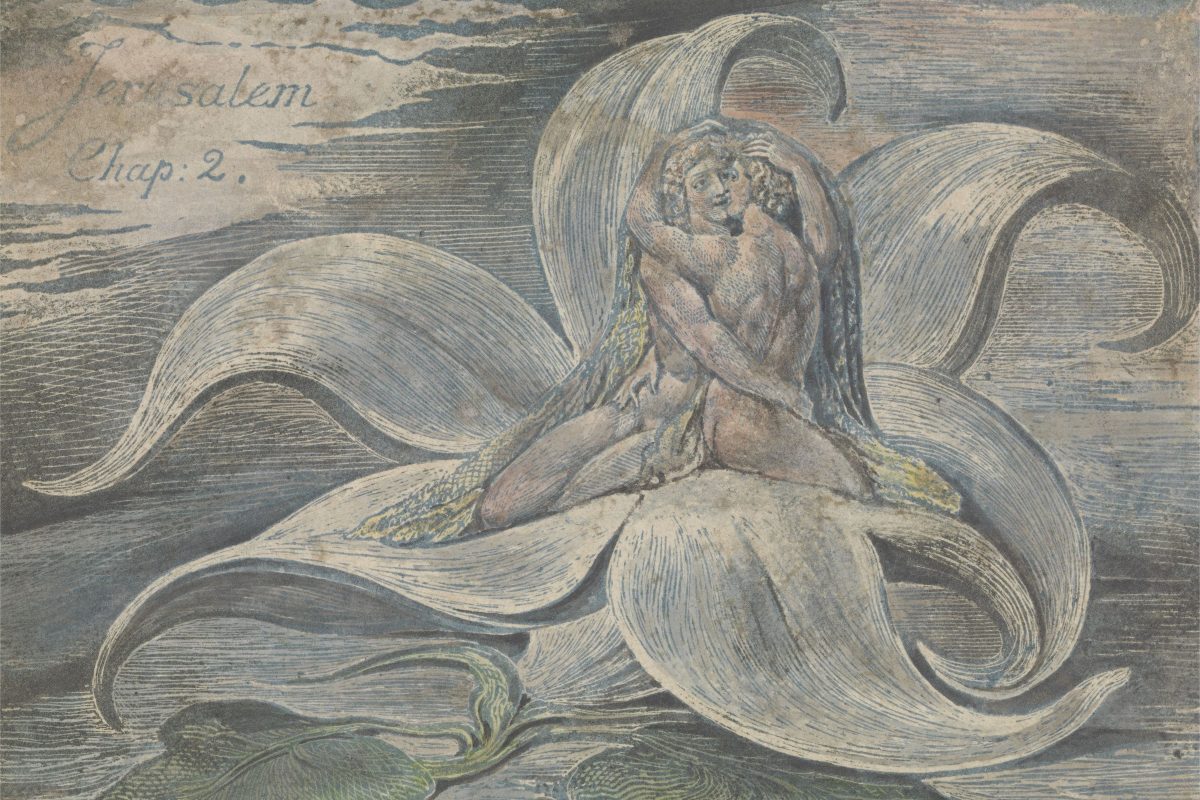

Jerusalem

The ruling class was eager to dampen the impact of the French Revolution on the English intelligentsia, which they rightly saw as a breeding ground for seditious ideas.

The ruling class was eager to dampen the impact of the French Revolution on the English intelligentsia, which they rightly saw as a breeding ground for seditious ideas.

In 1790, (the same year that Edmund Burke published his Reflections on the Revolution in France, and Blake his ‘Song of Liberty’) England’s most reactionary elements were organised into the ‘Church and King’ movement as a battering ram against radical politics.

And in 1791, when Paine published his Rights of Man (Part II), a Royal Proclamation against Seditious Writings was issued by the regime of William Pitt the Younger and George III. This was enforced through a vast network of informants and spies, tasked with rooting out all forms of political radicalism. This repression led Blake to quip that, had Jesus Christ been alive in those days, he would’ve ended up in one of Pitt’s prisons.

In this period of intense class struggle and turmoil, Blake moved to Lambeth. The formerly rural borough was at that time undergoing a rapid process of industrialisation. The hellish factories became the inspiration for the ‘dark Satanic Mills’ of one of Blake’s most famous compositions, ‘Jerusalem’. The poem rails against the monstrous conditions created by burgeoning capitalist production and yearns for its destruction. Blake vows “my sword [shall not] sleep in my hand: Till we have built Jerusalem, In England’s green & pleasant Land.”

Inspiration

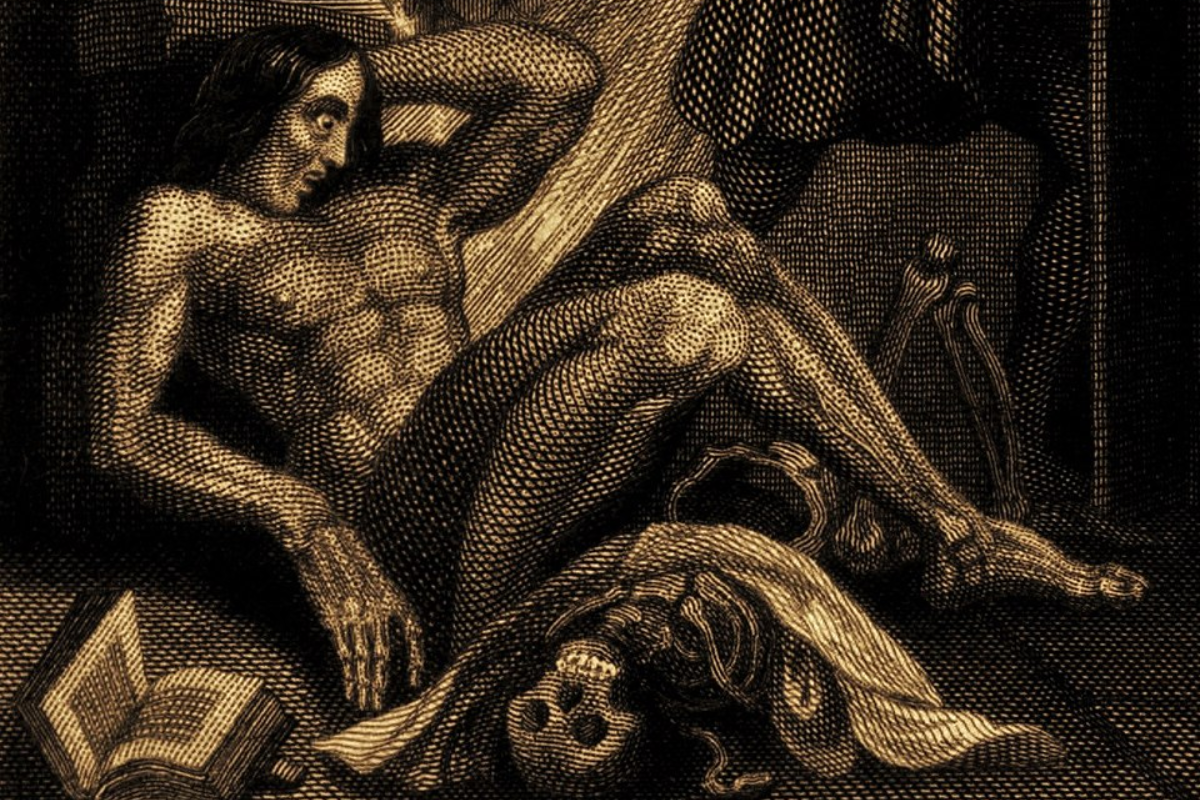

In addition to his poetry, Blake was also an accomplished painter and draughtsman. The ‘illuminated books’ he produced in this period also contained explicit condemnations of colonialism and the slave trade, which put him at risk of arrest for sedition. As a result, his works were only circulated on a small scale in private circles.

Blake was, of course, limited by his bourgeois outlook and could not have envisioned the revolutionary potential of the working class (then in its early infancy), nor the necessity of replacing capitalism with socialism. In later life, he grew disillusioned with revolutionary politics. However, his mark on cultural and political history is indelible, and the power of his work an inspiration to anyone striving for a better world.

‘William Blake: Rebel, Radical, Revolutionary’ Exhibition at Tate Britain (Pimlico, London) runs until 2 February 2020.