One hundred years ago Europe was in the middle of a bloody world war. With tensions rising in the Middle East, the Korean peninsula, and the South China Sea – and given whose fingers are on red buttons all over the world – should we be worried about the possibility of a similar situation today?

The unpredictable Donald Trump is in the White House. Earlier this year he seemed determined to provoke the unstable North Korean dictatorship over the question of nuclear weapons. The gangster Putin is ever more confident when it comes to flexing Russian military muscle – recent events in Ukraine and Syria have proved that. One hundred years ago Europe was in the middle of a bloody world war. Given whose fingers are on red buttons all over the world, should we be worried that we might be heading for a similar situation today?

Wars aren’t caused by accidents, or by the whims of individuals. War is the continuation of politics by other means. The First World War wasn’t caused by the chance meeting of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his assassin. It was caused by the fact that the major capitalist powers, in their scramble for new markets, inevitably came into a conflict which ultimately could only be settled by war. The Archduke’s assassination was just the accident that expressed this necessity.

Relations between the various capitalist powers, and the balance of class forces within each country and on a global scale, are the real determining factors when it comes to war. This is far more important than the individual psychology of Trump, Putin or Kim Jong-un.

Why hasn’t there already been a Third World War?

Much has been written about the causes of previous world wars, and this can help us understand what causes war to break out. But we can also learn something from understanding why there has not already been a third world war.

After 1945 there were two major superpowers in the world – the USA and the USSR. The nature of the USSR, i.e. a centrally planned, state-owned economy – in spite of the privileged bureaucratic caste at the top – brought it into direct conflict with the United States. And yet this competition didn’t lead to a world war. Why was this?

Firstly, the end of the Second World War opened up a period of unprecedented economic growth, which was the basis of the relative stability in the West. Stalinism in the East was also still expanding at a fast pace and able to stabilise its position. Thus the two major powers, although in conflict in Korea, then Vietnam, Afghanistan and so on, had no interest in coming into conflict with each other.

Secondly, on both sides of the Cold War there was an acute awareness amongst the ruling strata that war is the midwife of revolution. The First World War gave birth to the Russian Revolution in 1917, and to repeated attempts at revolution in Germany in 1918, 1919 and 1923.

At the end of the Second World War and in the post-war period class struggle was on the agenda once again. The Greek civil war broke out immediately after the end of the fascist occupation. In France and Italy there were powerful anti-Nazi resistance movements led by the Communist Parties. There was also a whole series of independence movements in colonial countries around the world – in Indonesia against Dutch rule, in Vietnam against France, in India against Britain, in China, Algeria, Egypt, Cuba, Iraq, Congo and so on. In China it led to Mao coming to power and the end of capitalism, albeit in a distorted Stalinist manner. In May 1968 France was rocked by the largest general strike in its history, and in 1974 the Carnation Revolution in Portugal overthrew the dictatorship and liberated Portuguese colonies. In Spain in the same period there was the revolutionary movement that brought down the hated Franco regime. The list could go on.

As for the USSR, the Stalinist dictatorship also provoked important movements of the working class. The 1953 uprising in East Germany, the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, riots throughout Czechoslovakia, strikes and protests in the USSR itself in the 1960s – all took place during the Cold War period.

Under these circumstances, neither the Western capitalists nor the Stalinist bureaucrats had any interest in provoking the masses by engaging in a bloody and expensive direct clash between the superpowers.

Thirdly, throughout the period of the Cold War the development of military technology, especially nuclear weapons, reached previously uncontemplated heights. It is a dialectical contradiction that this enormous potential power to destroy everything actually pushed world war even further from the realm of possibility. Nuclear war was simply too expensive, both politically and economically, for the USA or the USSR to consider as a serious option.

A war between nuclear powers would lead to death, destruction and horror on an unimaginable scale for millions of ordinary people who would suffer the nuclear holocaust. And nothing is more guaranteed to provoke a popular uprising of the many against the few than a decision to start a nuclear war. Politically, such action is far too expensive for the ruling class.

In addition to that, the purpose of any war is, ultimately, to conquer new markets and expand spheres of influence. But so great was the proliferation of nuclear weapons during the Cold War, and this continues today, that a nuclear war would not simply destroy one or two cities – it would wipe out entire countries and make a radioactive wasteland out of whole continents. Rather than conquering new markets, nuclear war would simply wipe them out. War between two major nuclear powers would thus be an act of economic self-sabotage from which the warring factions would stand to lose far more than they gained. There would be no “winners” in a generalised world nuclear war; the major powers would merely destroy each other.

Fourthly, the collapse of the USSR and the end of the Cold War pushed world war further down the agenda, as the USA assumed the position of being the world’s only superpower. With no other nation even close to being able to compete with the USA in terms of economic power or military might, serious conflict leading to major wars seemed to be ruled out.

However, although direct conflict between the powers was ruled out, there was a proliferation of local wars in which the major powers were and are heavily involved. Stating that a generalised third world war is ruled out in the coming period, does not mean that we have entered a period of worldwide peace. On the contrary!

A new epoch

The period of unquestioned omnipotence of US imperialism is now at an end. There’s no doubt that the USA is still the world’s foremost imperialist power, but in this new epoch that doesn’t necessarily mean that it is dominant in every region of the world at the same time. The US ruling class is suffering a relative decline in its imperialist strength.

This relative decline isn’t a new phenomenon, but it’s not by chance that the process has been accelerated and exposed since the economic crisis of 2008. Imperialist power is an expression of the economic strength of the ruling class of a particular nation. All politics, including foreign policy, is, in the final analysis, concentrated economics.

In the immediate post-war period the USA accounted for 50% of world GDP, but today that figure is around 20%. The US used to be the world’s biggest creditor, but today it is the world’s largest debtor. With the crisis of the world economy in 2008, confidence in the political and economic establishment also collapsed, especially on the question of expensive foreign military adventures. The exposure of the lies surrounding the Iraq war, and the disastrous consequences of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, such as the rise of ISIS, have further discredited the US ruling class’s imperialist policy in the eyes of the working class in the USA and around the world. Obama’s failure to pass a congressional vote in favour of bombing Syria in 2013 was a stark indication of the weakening of US imperialist power. All of this hints at the potential power of the working class when it comes to defeating imperialism. If we resist our own capitalist governments and their imperialist adventures, we can prevent war.

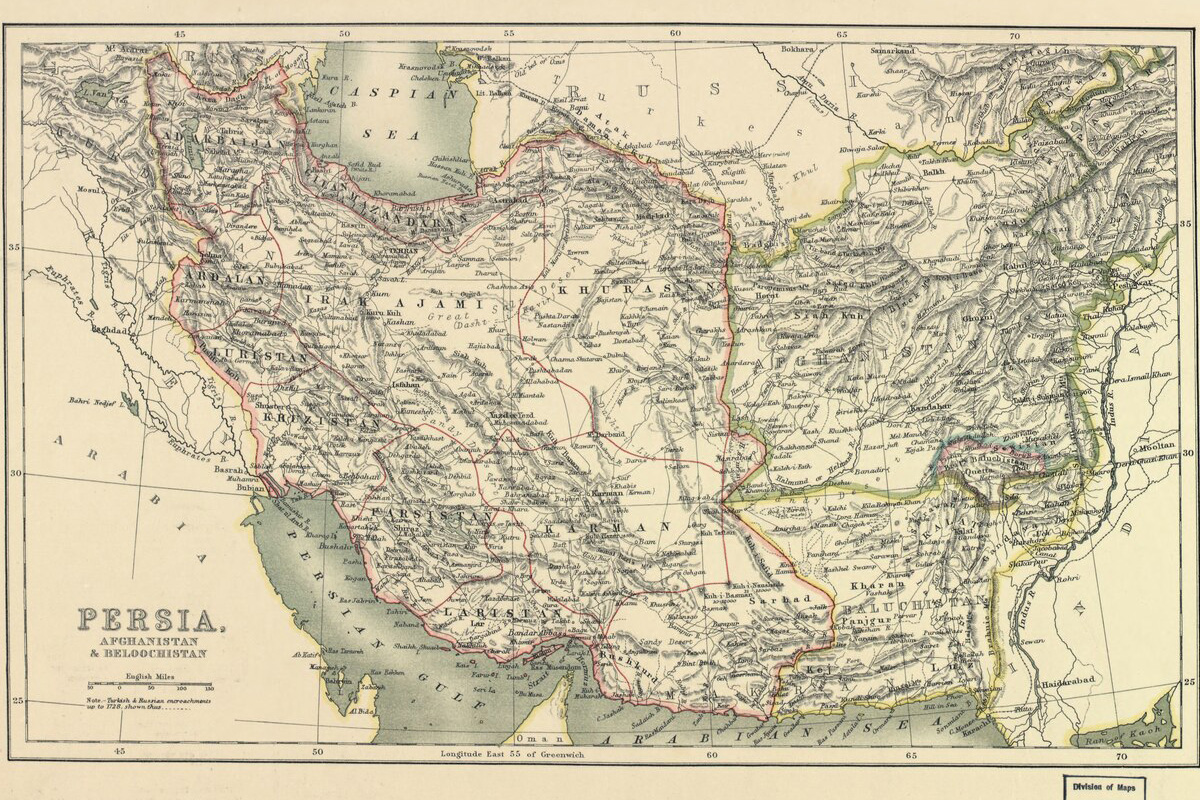

Does this relative decline of US imperialism mean that we’re now in a period equivalent to the period just before 1914, in which rival powers will struggle to re-divide the world amongst themselves? Is that what the current situation with North Korea means? Is that what the conflicts in Ukraine and Syria indicate? Does this mean that, like in the early 20th Century, this struggle will lead to a direct clash between the major powers – or in other words – a new world war?

The answer is that, yes there is a struggle between rival powers in the world at the present time, but no, this will not lead to a third world war in the coming period.

Russia and China

The relative decline of US power is causing cracks to open up in the US Empire and certain countries, most notably Russia and China, are seizing the opportunity to exploit these weaknesses.

The relative decline of US power is causing cracks to open up in the US Empire and certain countries, most notably Russia and China, are seizing the opportunity to exploit these weaknesses.

In Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine in 2014 Russia was able to defeat the attempts by US imperialism to sign those states up to the NATO alliance. After two decades of eastward expansion by NATO the conflicts in Georgia and Ukraine were defeats for US imperialism, and successes for Russia’s efforts to assert itself in its traditional spheres of influence.

The conflict in Syria is indicative of the same thing. Putin is master of the situation in Syria and has been able to outmanoeuvre the US imperialists throughout the civil war. Russia has even been able to begin to prise Turkey away from its loyalty to the NATO alliance by involving Erdogan in negotiations over Syria while excluding the USA.

Meanwhile China’s island building programme in the South China Sea, and its courtship of regional governments, for example in the Philippines, Thailand and Sri Lanka, are eroding US influence in south-east Asia. China is adopting a softly-softly strategy of winning regional powers away from alliance with the USA and towards its own sphere of influence. Each time US imperialism is unable to assert itself, for example in Ukraine or Syria, China readily highlights this fact to governments in Vietnam and South Korea.

The relative decline of US imperialism can’t help but cause its allies to question whether an alliance with the US is worth the paper it is written on – a doubt that China is keen to encourage. The Chinese ruling class is pointedly asking other regional governments: if the US can’t intervene to help its allies in Eastern Europe or the Middle East, what’s to say it wouldn’t also abandon its allies in south-east Asia?

North Korea

This is the context in which tensions over North Korea developed in the first half of 2017. The US ruling class can feel its power in decline, and it can see China and Russia moving in on its traditional spheres of influence. When something as powerful as US imperialism feels itself backed into a corner, it’s bound to lash out. And when this general attitude of the US ruling class is filtered through a character like Donald Trump as president, the reaction is inevitably reckless.

Trump ramped up pressure over North Korea for three reasons. Firstly, it is an excuse for the USA to flex some muscle in the region in an attempt to quell fears amongst its allies that US imperialism is not as powerful as it used to be. Trump sent the US navy to the region. US jets flew training exercises with the Japanese and South Korean air forces. He invited the president of the Philippines to the White House, and spoke on the phone with every political leader in the region about the North Korean crisis. All of this is the US ruling class trying to send a message that it is still the boss in south-east Asia.

This also partly explains the launch of 59 US missiles into Syria while Trump was eating dinner with the Chinese president. When interviewed about the missile strike Trump was able to recall the details of his dinner with Xi Jinping, but couldn’t remember which country he had just launched missiles at, telling the interviewer that they had hit in Iraq, when in fact they had hit Syria. This indicates much more than Trump’s buffoonery. It indicates that, for him, the most important thing was that he was with Xi Jinping when the US fired its missiles. Their target was of secondary importance because Trump was sending a warning to China: the USA has enormous military power and is prepared to use it.

The second reason why the US is ramping up pressure over North Korea is to play China at its own game. By provoking the unstable North Korean regime, the US is forcing China to join it in putting pressure on Kim Jong-un to scale back his nuclear programme. In other words, Trump is trying to drive a wedge between China and one of its regional allies. The intention is to prove to other regional powers that an alliance with China is no more stable than an alliance with the USA and that, if the US flexes its muscles, China is not guaranteed to stand up for its allies.

Finally, Trump is facing problems on the domestic front. His legislative efforts have not gone as smoothly as he had hoped, even with Republicans in the majority of both houses of Congress. And he is facing continued pressure over his associates’ dealings with Russia. On top of that he is extremely unpopular among a huge percentage of the US population. Battling an external enemy is always a good way for bourgeois governments to cut across splits in the ruling class and rising class struggle, at least for a time, and North Korea is an obvious target.

Are we on the path to war?

Growing tension in international relations does not automatically equal war. War is the continuation of politics by other means, and there are many political, economic and social processes which are pulling the world’s major imperialist powers away from world war, not towards it.

The First World War broke out at a peak of capitalist development, when rival empires had decades of growth and expansion behind them. This gave the British, German, French and other belligerent ruling classes confidence in themselves and their ability to enter into direct military confrontation with each other.

The opposite is the case today. Since 2008 every national ruling class has been presiding over economic, social and political crisis to varying degrees. And before 2008, for many decades US imperialism was the dominant power in a world where capitalism was reaching and exceeding its limits everywhere. This is the opposite of the dominant role British imperialism was playing in the years prior to 1914, when capitalism was in its ascendency. This leaves US imperialism lacking the confidence necessary to directly confront the powers now challenging its position.

This is starkly illustrated by the fact that the world’s most powerful imperialist nation, the USA, is today heavily indebted to the world’s second economic power, China. This mutual dependence of the two most powerful nations is an indication of the weakness of the global capitalist class today – its two most powerful pillars are unable to support themselves; instead they’re forced to lean on each other to keep the system upright. On top of this, China is facing a looming economic crisis and, when this crisis hits, it will generate a whirlpool that has the potential to drag the rest of the world economy into its depths. Under all these circumstances, it’s not in the interests of either the US or the Chinese ruling class for their nations to clash militarily.

But more important than the respective positions of different wings of the ruling class, is the relationship between the working class and the ruling class on a world scale. The global working class is numerically stronger than it has ever been at any point in history. The worldwide crisis of capitalism has thrust workers in every country into the same boat – we’re all victims of cuts, austerity and accelerating inequality, from Greece to Brazil. Class consciousness and solidarity that transcends national borders is on the increase and workers can use this internationalism to wage class struggle against any capitalists who would have us fight our comrades in other countries just for the sake of their profits.

This class consciousness is what ended the First World War 100 years ago, through the Russian and German Revolutions. It’s also what prevented the bombing of Syria by the US and Britain in 2013, and what inspired two million people onto the streets in 2003 to oppose the invasion of Iraq. The more global and deadly the war, the more likely it would be to provoke massive working class opposition.

In the case of the USA this class-based opposition would acquire a particularly acute character, if Trump ever made moves towards a world war. He was elected on the basis of a campaign which promised that the USA would not pursue an interventionist foreign policy. This was popular because the disasters of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars have left the US workers sick of foreign interventions. If Trump were to renege on this promise – and not just renege in a small way, but launch into a direct military confrontation with a major world power – this would provoke an immediate and radical response from enraged American workers and youth, including many Trump voters who would turn against the President.

The power of the working class

The power of the working class when it becomes conscious of its strength and embarks on the road of class struggle was demonstrated in the Arab Revolutions of 2011. In Tunisia and Egypt mass movements toppled the long-term dictators Ben Ali and Hosni Mubarak – the latter a key ally of US imperialism in the region. From Tunisia and Egypt the revolutions spread, threatening at one point to become a regional revolution involving the whole of the Middle East and North Africa.

The power of the working class when it becomes conscious of its strength and embarks on the road of class struggle was demonstrated in the Arab Revolutions of 2011. In Tunisia and Egypt mass movements toppled the long-term dictators Ben Ali and Hosni Mubarak – the latter a key ally of US imperialism in the region. From Tunisia and Egypt the revolutions spread, threatening at one point to become a regional revolution involving the whole of the Middle East and North Africa.

It’s not just rival powers, such as China, that are capable of picking off US allies and hampering the imperialists’ ability to wage war. Mass movements of working class people can sabotage imperialist interests and overthrow imperialist regimes and their puppets and client governments when the masses become conscious of their own strength. This is the way to resist moves towards military conflict between nations. Wherever we are in the world, the best way to fight war and imperialism is by fighting our own ruling class in this way.

But North Africa and the Middle East also furnish us with examples of what happens when the old pro-war, pro-imperialist regimes enter into crisis but the working class doesn’t have organisations strong enough to allow it to seize power for itself.

In Syria the working class has been unable to assert itself as an independent force in the civil war that has racked the country. This has been caused by, and has also been an opportunity for, intervention by regional imperialist powers such as Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Iran, and Russia, each trying to assert their own narrow interests, all at the expense of the Syrian masses.

The crisis in Syria highlights the need for mass movements of workers and young people to have an idea of what they are for, as well as what they are against, and how to go about fighting for and building it. This means policies, a programme and a political party through which the working class can organise itself independently, to act in its own interests. This is the role of a revolutionary socialist organisation based on Marxist theory.

The barbarity in Syria today shows what can happen without such an organisation. It shows how a movement with the potential to end war can turn into its opposite under the pressure of intervention by foreign imperialism. The working class must anticipate this action on the part of the international ruling class and build organisations capable of resisting it, if our struggle against war and imperialism is to be successful.

What does the future hold?

In one sense the Syrian situation could be called a world conflict, because so many different powers are involved in the conflict by proxy. But this is not what we traditionally understand by the term ‘world war’, in the sense of being a direct confrontation between major imperialist powers that results in a decisive settlement of their competition for markets and spheres of influence on a world scale.

Such a world war is not on the cards in the near future, for all the reasons outlined above. The weakness of capitalism and the potential power of the working class makes a deliberate and direct military confrontation between major imperialist powers impossible. However, this doesn’t rule out smaller, and equally horrific, local and regional wars and massive instability in the coming period.

US imperialism remains the strongest on the planet and its decline will be slow and painful. As China, Russia and other nations exploit the weakening of US influence and power, we are sure to see erratic, provocative and dangerous behaviour on the part of the US ruling class as it tries to cling onto its dominant position.

This will mean instability in the formerly “peaceful and prosperous” countries of southeast Asia, and it will mean splits in the ruling classes of the counties in this region as the US and Chinese compete for influence. In this region, and elsewhere around the globe, the possibility of proxy wars between the major powers is a serious one, and as we have seen with wars in Ukraine and Syria in recent years, there’s no doubt that conflict of this kind would be bloody and barbarous.

Unlike the Cold War, proxy wars in the coming period will not be fought out by just two opposing sides, but by many competing ruling cliques with regional and global imperialist ambitions. This will give future conflicts a degree of unpredictability that hasn’t been seen before.

The barbarism into which the global ruling class is willing to drag us in its bickering over markets and profits will be exposed by such conflicts for all to see. It will push people to draw radical conclusions – specifically that war, death and misery are the product of the rich vying for power, influence and ultimately profit. The most important conclusion that people will start to draw in the coming period is that it is the capitalist system as a whole which has reached a dead end, and that we must organise to overthrow it. The independent intervention of the masses in the conflict between rival capitalist powers, in defence of working class interests, can be decisive. Our future is one of socialism or barbarism – the working class, ultimately, has the power to decide.

In the long run, if the world working class fails to transform society, fails to put an end to the rule of capital, then a major war is not ruled out at all. But before that happens we have before us a historical period in which the workers and youth of all countries will move again and again in an attempt to change society. It is the outcome of these struggles that will determine the long-term prospects for war or not. This perspective make it even more urgent to build the “subjective factor”: an international party capable of leading the workers in all countries in a revolutionary overthrow of the capitalist system that has already dragged us into two world wars.