Since the beginning of the crisis of 2008, anti-immigrant parties and movements have made headway in Europe and the United States. They have even managed to win over certain layers of the working class to their programme. This has led a section of the labour movement to adapt itself to these ideas, calling for stricter border controls, justifying its position with quotations from Marx. But such short-sighted policies have nothing to do with Marxism.

[This article is an extract from a longer piece, recently published on In Defence of Marxism.]

One of the main fields in which this discussion has played out has been on the question of Brexit. In particular, right-wing politicians have drawn the conclusion that the reason behind Brexit was that workers were racist and therefore we have to “listen to their concerns”.

This has also affected the trade union movement, where a number of leading union officials have come out in one way or another for more restrictions on immigration.

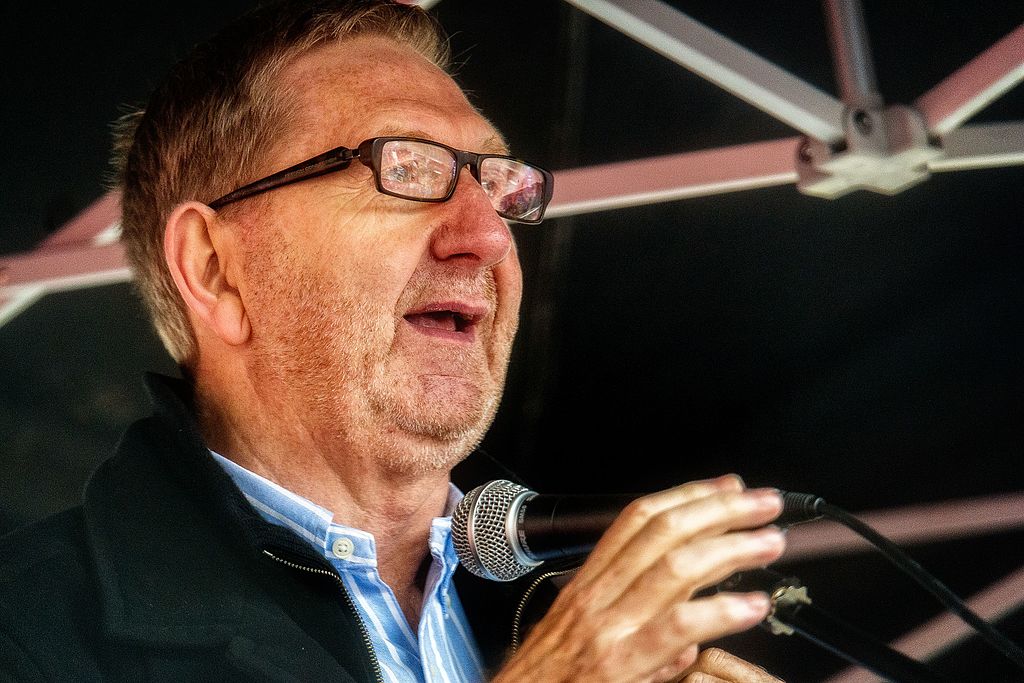

In December last year, Unite the Union leader, Len McCluskey penned an article entitled “a second Brexit referendum risks tearing our society apart”. In general, the article is a sensible critique of the movement for a second referendum, which indeed does threaten to tear the Labour Party apart.

In the article, however, McCluskey returns to the theme of border controls. He calls for an end to imported agency labour where it undercuts local term and conditions. This is correct. The Labour movement must fight against any attempts to undermine the positions it has already conquered. This includes the EU’s Posted Workers Directive, which has opened the door for what is effectively the import of strike-breakers from other parts of Europe.

But the Unite general secretary then continues and steps over a line from what is a correct position to a dangerous one:

“The working-class movement will always fight against racism – and exploitation too. And any trade unionist will know that our strength always needs underpinning by control of the labour supply – a deregulated free market for labour power works no better than it does in any other part of life.”

This common sense rhetoric hides quite a pernicious demand: that we should allow the capitalists to determine the labour supply. He implies that somehow the trade unions could control the labour supply. But he doesn’t even spell it out, because he knows that’s not on the agenda. He’s referring to the capitalist state controlling immigration, at the head of which at the moment is a very anti-union government.

In reality, this is an appeal for the capitalists to limit immigration, not for immigration control by the labour movement. If he was arguing for the closed shop, where only union members are allowed to work, a Marxist would find no reason to object. But that’s not what he’s saying here.

Marx and migration

In reality, McCluskey knows he’s on shaky ground, which is why he attempts to use Marx and anti-capitalist rhetoric to defend his position.

In reality, McCluskey knows he’s on shaky ground, which is why he attempts to use Marx and anti-capitalist rhetoric to defend his position.

Back in December 2016, McCluskey published an article in the British Communist Party paper, Morning Star as part of his re-election campaign. The article was clearly directed towards Len McCluskey’s left-wing opponent, Ian Allinson, who wrote an earlier article supporting the rights of workers to move freely.

Among other arguments, Allinson cites the example of women in the workplace – and it’s a good analogy. The demand for women to stay out of the workplace and the unions was a reactionary, divisive demand, and helped bosses create different rates for women and men and thereby use women to undermine male workers’ pay and conditions. All the objections that are made to the presence of migrant workers were made about women workers in the past. There is no reason to treat immigrants differently.

In order to defend his position, McCluskey quotes Karl Marx:

“A study of the struggle waged by the English working class reveals that, in order to oppose their workers, the employers either bring in workers from abroad or else transfer manufacture to countries where there is a cheap labour force.”

From this little snippet, McCluskey is attempting to infer that Marx supported border controls. But if we read the full paragraph, we get a rather different picture:

“The power of the human individual has disappeared before the power of capital, in the factory the worker is now nothing but a cog in the machine. In order to recover his individuality, the worker has had to unite together with others and create associations to defend his wages and his life. Until today these associations had remained purely local, while the power of capital, thanks to new industrial inventions, is increasing day by day; furthermore in many cases national associations have become powerless: a study of the struggle waged by the English working class reveals that, in order to oppose their workers, the employers either bring in workers from abroad or else transfer manufacture to countries where there is a cheap labour force. Given this state of affairs, if the working class wishes to continue its struggle with some chance of success, the national organisations must become international.” (Marx, On the Lausanne Congress)

Marx recognises the problem: that employers are using national divisions and borders in order to pit the working class against itself. However, his solution isn’t ‘managed migration’, but international organisation. Marx calls for increased cooperation between labour movements across borders. Indeed, the particular passage quoted is from the Lausanne Congress of the International Working Men’s Association (the First International), which Marx dedicated himself to building.

It would never have crossed Marx’s mind to campaign for border controls. There’s a world of difference between arguing that all workers in Britain should be working under the same pay and conditions, and arguing for a ban or limit on foreign workers. The former serves to unite the working class, the latter to divide it.

Unity in struggle

In reality, McCluskey’s article is an attempt to establish a left cover for ‘managed migration’, by which he clearly means reduced migration. This has been the catch-all phrase for the Labour Party’s migration policy for at least two decades: from Tony Blair’s detention centres; to Brown’s slogan “British jobs for British workers” (launched at a trade union conference in 2007); to Ed Miliband’s infamous “Controls on Immigration” mug in Labour’s 2015 general election campaign.

In reality, McCluskey’s article is an attempt to establish a left cover for ‘managed migration’, by which he clearly means reduced migration. This has been the catch-all phrase for the Labour Party’s migration policy for at least two decades: from Tony Blair’s detention centres; to Brown’s slogan “British jobs for British workers” (launched at a trade union conference in 2007); to Ed Miliband’s infamous “Controls on Immigration” mug in Labour’s 2015 general election campaign.

One example, from the history of McCluskey’s own union, is the much-publicised Lindsey Oil Refinery strikes in 2009, where workers did precisely fight against undercutting terms and conditions by the Posted Workers Directive.

In this strike, local shop stewards fought to maintain an internationalist point of view against the establishment racists, who were trying without success to take over the strike. The shop stewards demanded that all workers, regardless of nationality, should be subject to the same conditions. The struggle was won after winning over the foreign workers to the strike, something that could never have been achieved if there had been an ounce of xenophobia in the campaign.

The trade union bureaucracy at the time, incidentally, was susceptible to the xenophobic slogan of the tabloid newspapers (put forward by Gordon Brown): “British jobs for British workers”. This slogan was picked up by then union leader Derek Simpson, who was supposed to be a left-winger. Clearly the workers, through their struggle, were able to develop a far better position on this question than the tops of the trade unions.

The myth of the liberal bourgeoisie

For the so-called ‘liberal’ elites, it is not a question of demanding open borders, but simply of wanting more ‘humane’ and efficient borders.

According to Tony Blair, a darling of the liberal establishment, “You’ve got to deal with legitimate grievances and answer them, which is why today in Europe you cannot possibly stand for election unless you’ve got a strong position on immigration because people are worried about it.”

“You’ve got to answer those problems,” the former prime minister has asserted. “If you don’t answer them then…you leave a large space into which the populists can march.” (Clinton, Blair, Renzi: why we lost, and how to fight back)

Blair, being a skilled bourgeois politician, never says anything clearly on these questions, but only drops hints. We need “a strong position on immigration” – but he doesn’t say what that would be.

It should be remembered that Blair’s immigration policy – ‘managed migration’ – involved setting up private detention centres where immigrants were treated worse than criminals. His party used to hand out leaflets bragging about reductions in the number of asylum seekers etc.

Much of the so-called hostile environment that asks doctors, teachers, lecturers, banks and landlords to police immigration existed in embryonic form during the Blair years. So one can presume that he proposes more of the same.

In Europe, Angela Merkel is often touted as a friend of immigrants. But she’s nothing of the sort. Admittedly, during the refugee crisis, she allowed more refugees into Germany than were allowed anywhere else. But that was not out of general approval of immigration.

In reality, she was attempting to stop freedom of movement from breaking down completely in the European Union. Borders were being erected between member states and this was a way of easing the pressure while she was working to stem the flow of refugees. In the end, a deal was struck with Erdogan, where he accepted €6bn to keep the refugees, at gunpoint, in Turkey. Such is the great humanitarianism of the European Union.

In the US, the Democrats – although not quite as far to the right as Trump – still defend most of his programme. Their main criticism is that he makes the establishment look bad. ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) is fine, but children should be deported together with their parents, not separately. While the Republicans advocate detention centres, the Democrats call for electronic tagging, because it is cheaper.

This myth of the liberal bourgeoisie exists on both the pro-immigrant and anti-immigrant left. Paul Mason (although he has changed his position multiple times) in 2016 argued that Labour must form an alliance with the “globalist section of the elite” for a soft Brexit.

One also finds this attitude across the entire pro-EU British left. They are constantly referring to the EU as some kind of progressive institution. And, although they might not use the same phrase as Mason, they argue for precisely the same: a cross-class alliance between the workers and the bankers of the City of London, the vast majority of whom supported remain.

To pretend that the bourgeoisie can in any way be a friend of the migrant workers or an ally of those that want to struggle against racism and xenophobia is to provide a useful service to the bourgeoisie, giving them a left, ‘progressive’ cover.

As Marxists, our role is to unmask the reactionary motivations behind both the section of the bourgeoisie that conceals its interests behind progressive, democratic colours, and of the section of the bourgeoisie that pretends to be on the side of the native worker against the foreign.

Anti-imperialism?

The left proponents of migration controls occasionally justify immigration controls by reference to international solidarity. Surely migration is bad for the countries where people are emigrating from, and shouldn’t we be in favour of improving conditions there instead?

The left proponents of migration controls occasionally justify immigration controls by reference to international solidarity. Surely migration is bad for the countries where people are emigrating from, and shouldn’t we be in favour of improving conditions there instead?

This sounds pleasant enough, but the question is: how should we improve conditions? Furthermore, given that the working class is not actually in power, what demands would serve to get us to that point?

For all the pious phrases of the world leaders, they always look after their own interests first. By keeping migrants out, the US ruling class is helping stave off the class struggle at home, at the expense, of course, of Mexico and Central American countries. This is also the policy of the EU in relation Turkey. This is how imperialism works.

In the popular imagination, of course, charitable organisations and foreign aid serve the purpose of helping the impoverished masses of the world. In reality, charities mainly line their own pockets and those of corrupt government officials around the world. The workers and poor have to settle for crumbs. At best, charities cover up for the damage that is done by the armies and banks of the imperialist nations.

In reality, it’s no good talking about changing the conditions in the former colonial world without challenging capitalism and imperialism itself. The whole of the 20th century shows the futility of anti-imperialism without anti-capitalism and socialism. Precisely because imperialism is intrinsically linked with capitalism, so the struggle against imperialism must be linked to the struggle against capitalism.

Any other proposals, particularly coming out of the labour movement in the imperialist countries, would merely be providing a left cover for imperialism. The workers of the imperialist countries need to unite with workers in the former colonial world by fighting against their own imperialist bourgeoisie. This is real international solidarity.

For world revolution

It’s one of the peculiarities of the present period that the labour movement in the west is infected with nostalgia for a period that has passed.

It’s one of the peculiarities of the present period that the labour movement in the west is infected with nostalgia for a period that has passed.

Under the pressure of cuts to public services and attacks on pay and conditions, many workers look back to a previous era as one of stability and welfare: to a time when the capitalists and trade unions made agreements about wage rises, not wage cuts, and when political parties promised – and delivered – reforms. But that period is gone and will not return.

The crisis is not due to migrants, nor bad ideas (‘neoliberalism’), but the limits of capitalism itself. This has certain implications. The reformists and trade union leaders fall into the trap of basing their approach to migration on the number of migrants that capitalism can afford. How many migrants can come without causing downward pressure on wages? How many migrants can we fit in schools, housing and hospitals?

This was wrong in the 1950s and 1960s, but it’s a disastrous logic in a period of capitalist decay. The answer is that capitalism can not afford to maintain the existing wages and conditions, whether there are migrants or not. Closing the borders, even evicting migrants, does not fundamentally alter this fact. It’d be like attempting to quench your thirst with salt water.

The reality of capitalism in the present period is that there is the money to provide housing, schools etc. for all the refugees in the world, but it’s in private hands. The resources to provide a decent living standard for all the world’s inhabitants exist, but they are concentrated in the clutches of a tiny handful of billionaires and multinational corporations. This inequality is only getting worse.

Our programme is not about achieving stability and accommodation with the capitalist class, which would only be at the expense of the working class, migrant or not. Our programme must be one of uniting workers across borders in defence of conditions, against cuts and for a socialist revolution.

This programme must include: defence of collective bargaining agreements, terms and conditions; a struggle for an improvement in the conditions of all workers; and the granting of the same rights to migrants as non-migrant workers, including residency, health care, social benefits, housing. Furthermore, we must insist on building links between unions internationally and the strengthening of ties between working-class organisations across the world.

Such an approach will be the best defence of the existing conditions of the working class, against the onslaught of the ruling class. But it is also the best preparation for a worldwide socialist revolution.