2024 is a year of anniversaries for the British labour movement.

Among those, this year marks the 52nd anniversary of one of this country’s greatest class battles, the miners’ strike of 1972, as well as the fifty-year anniversary of the toppling of Heath’s Tory government in 1974.

These miners’ strikes were some of the stormiest struggles this country has ever seen, and the lessons they hold for today are as sharp as ever.

Back then, as now, the Tories under Ted Heath were hell-bent on bringing organised workers to heel so as to shore-up an increasingly shaky British capitalism. Their weapon of choice was the Industrial Relations Act, made law in 1971.

This was intended to curtail the power of the unions by, amongst other things, narrowing the definition of what constituted a ‘legal’ dispute or strike in order to prevent major battles from taking place. This was similar to today’s Minimum Service Levels laws, which now give bosses the right to order workers to scab on their own strikes.

The Industrial Relations Act, a veritable ‘scabs charter’, far from ending industrial unrest, instead provoked fury amongst a wide range of workers.

Having endured years of real wage erosion and job losses, pressure was building for action within the ranks of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM).

Miners begin to move

The NUM’s leadership at that time was in the hands of the right wing. The then-general secretary, Joe Gormley, was so in-hock to the establishment that he was even alleged to have regularly passed information on ‘union militants’ to Special Branch!

And yet, despite leaders like this, the miners were mobilising. A series of unofficial strikes in the late ‘60s reflected the increasing confidence in industrial action amongst the membership.

By 1972 the demand for national action was too great to resist. A pit head ballot had returned a 58.8% majority in favour of strike action.

Demanding a 47% pay increase to make up for the erosion they’d been forced to endure, the miners began walking out on 5 February 1972. This was the first time they had taken national strike action officially since the 1926 General Strike.

The response to the strike call was tremendous, particularly in Yorkshire and in the South Wales coalfield. Shaken, Heath and the Tories declared a national state of emergency, showing how seriously they took the situation.

The movement spreads

With the pits at a standstill, attention was turned to the coal stocks. Flying pickets were used to target supplies. They received widespread solidarity from the rest of the working class.

Such was the mood that the TUC adopted an instruction for its component unions not to handle coal, a call that got a huge response from delivery drivers and railway workers alike.

Combined with the NUM’s flying pickets, which prevented coal deliveries from depots, it was clear that the Tories were on the ropes. The miners’ cause, combined with wider anger about the Industrial Relations Act, had galvanised hundreds of thousands into struggle.

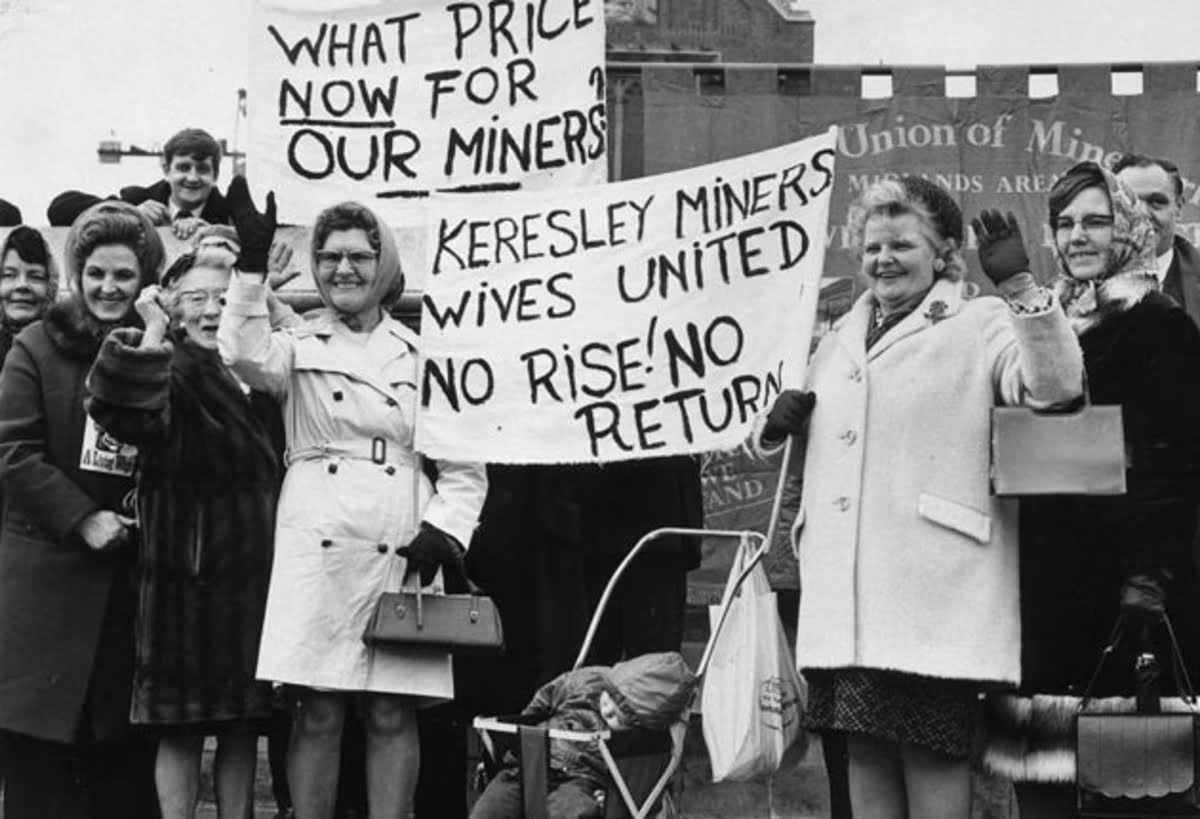

The attention of the miners turned to the coke depot at Saltley Gasworks in Birmingham, the last remaining open fuel depot in the region. Pickets were dispatched and on 8 February, 1,800 Midland car delivery workers came out in sympathy.

A meeting of shop stewards in the engineering industry called for action. As a result 40,000 workers took action and some 10,000 marched on Saltley Gate and closed the plant.

This was a turning point. In the end the Tories were forced to give way.

Maudlin, the Home Secretary, was asked why they had not used troops. He replied: “I remember asking them a single question: ‘If they had been sent in, should they have gone in with rifles loaded or unloaded?’ Either course could have been disastrous.”

The miners had drawn first blood.

“Who runs the country?”

When the Tories then tried to settle accounts with the dockers, they got another nasty shock. When dockers who had been imprisoned thanks to powers brought in by the Industrial Relations Act – the ‘Pentonville Five’ – there was enormous fury and rolling strike action in solidarity.

So big was the scale, that it forced the TUC to call a one-day general strike, before an unofficial one developed! The Pentonville Five were released, marking another victory for the workers.

1972 was a turning-point.

By the end of 1973, inflation was really beginning to bite. Once again, the miners entered the fray – this time, their national ballot returned an 81% majority for strike action over pay.

The government had introduced a state of emergency and a three-day week was imposed, supposedly to save energy. By the middle of January, one million workers had been laid off.

Fearing a repeat of 1972, Heath and the Tories gambled all on a snap general election under the slogan ‘who runs things – us or the unions?’

The public, and especially the working class, answered ‘the unions’, and voted them out. To add the cherry on the cake, the miners got the majority of concessions they were looking for, and 11 March saw them return to work once more.

This example demonstrated the colossal power of the working class when mobilised. For the first time in Britain, the working class had brought down a government using its industrial strength.

It showed that not a wheel turned, a light shone, or anything moved, without the kind permission of the working class.

Today

Today, the whole working class finds itself in a similar situation to that of the miners in ‘72. After decades of pay erosion, 2022-23 saw a return to the industrial front. Everywhere in Britain, workers began to move onto the pickets, the majority for the first time in their lives.

This movement is still at a very early stage. Having had a glimpse of their potential power over the course of the last strike wave, many workers now see mass industrial action as the way to get what they need.

Whether it faces a Tory or a Labour government, this rising layer will – sooner or later – take the road the miners took in 1972 and 1974.

When that happens, and provided it learns the lessons of the past, the chance will come for it to topple not just a government, but challenge the whole capitalist system.

–

To learn more about this stormy period in detail, we highly recommend In the Cause of Labour by Rob Sewell. The book covers the whole history of the British labour movement, and is full of valuable lessons for today. Visit wellredbooks.co.uk to get your copy.