Five months in, and Starmer’s Labour government has carried out a reset. Far from bringing in the change that workers want and need, however, more chaos is on the menu.

The list of attacks is eye-watering. ‘Efficiency savings’ of 5 percent in most major government departments. A paltry 2.8 percent public sector pay rise, which in most cases is set to come out of existing budgets, rather from new money. Blatantly favouring academy schools over state schools for funding. And NHS England staff left confused as to which diktats on performance are supposed to be obeyed first.

Workers in industry are faring little better, meanwhile, with closures and jobs massacres either underway or on the cards at the Port Talbot steelworks, Grangemouth oil refinery, and Vauxhall’s Luton factory, to name but a few.

All this is naturally provoking resentment. Among the working class, patience is wearing thin.

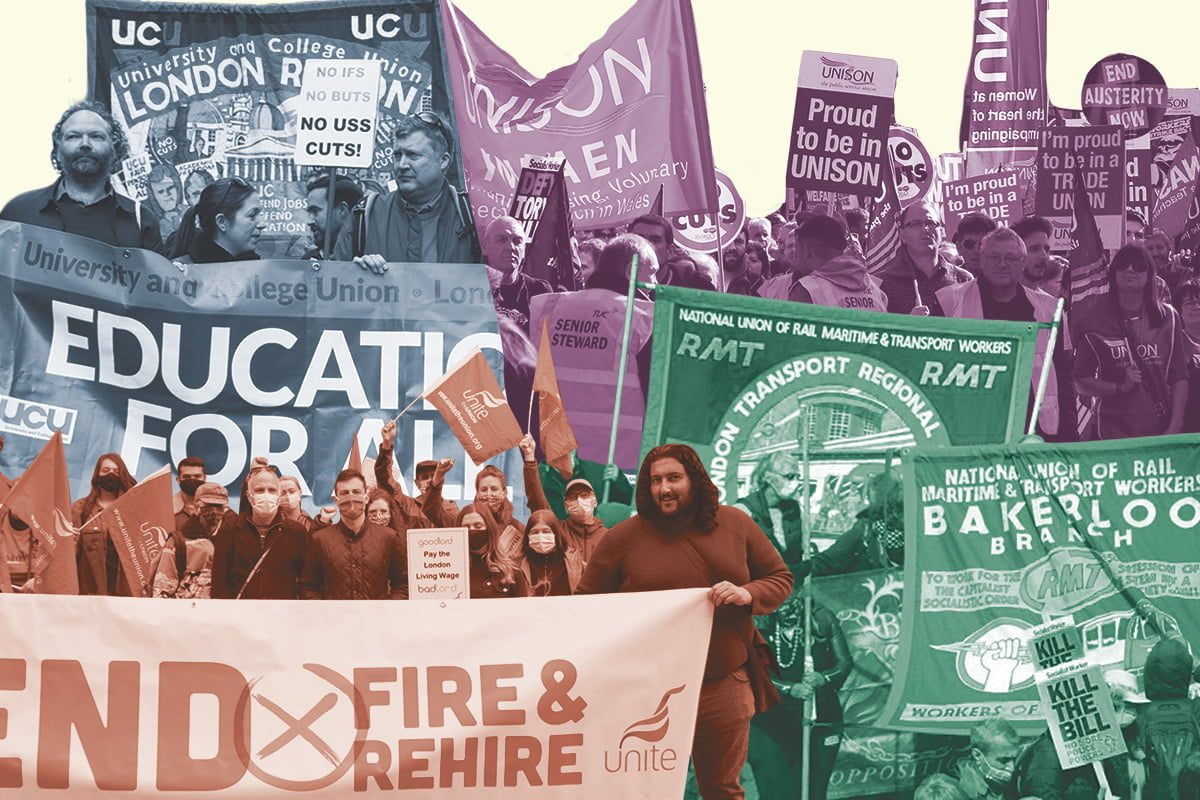

If ever there was a time for a serious strategy of organisation, mobilisation, and action to defend workers’ interests, that time is now.

But it is at this precise moment that heavyweight unions – the biggest battalions of the labour movement, representing millions of workers across the public and private sector – are turning inwards.

Instead of preparing rank-and-file members for class struggle, trade union leaders are expending their energies on factional struggles.

Knives out

Unite, which organises in both the public and private sectors, has seen near-constant infighting since the election of Sharon Graham as general secretary.

The old United Left (UL) still has a grip on much of the apparatus. Graham’s camp, however, is sniping at its opponents by bringing up corruption allegations, such as those surrounding the construction of the union’s flagship conference centre and hotel.

It is of course possible – even probable – that many officials within the Unite bureaucracy are corrupt, whichever faction they have ended up in.

But despairing workers at Port Talbot and Grangemouth must be looking at this mudslinging, and wondering why their union leaders have not put as much effort into fighting the bosses as they do into sparring with each other.

Similarly, during the tremendous strike wave of 2022-23, rather than organising any serious fightback, Unison’s right-wing leadership and officialdom spent most of their time waging an internal war against the left, organised around Time for Real Change.

Since then, the ‘strategy’ of the Unison leaders – as much as there has been one – has been based on buttering up the new Labour government, with very little to show for their craven servility.

As they dither, Time for Real Change is beginning to regroup around the campaign to elect Andrea Egan as General Secretary. And there is every possibility that she could tap into the discontent amongst grassroots members.

In GMB, meanwhile, the union leadership has been fending off an increasingly serious string of internal complaints from its own members. These allegations follow on from an independent inquiry in 2020, which reported that “bullying, misogyny, cronyism, and sexual harassment are endemic” within the union.

We are not in a position to comment on the veracity – or otherwise – of these claims. But it seems that the GMB’s leaders are facing a storm most likely of their own making, just as their members face attacks in local councils and collapsing industries.

The situation is not much better in smaller unions. PCS’ national strategy has stalled several times due to ongoing internal battles between the Left Unity and Alliance for Change factions, the latter of which now controls the union’s NEC by a slim margin.

And in the FBU, where general secretary elections are currently underway, factional fighting has reached such a virulent stage that the union has publicly commented on the need to “stop personal abuse” in the campaigning.

Paralysis

Of course, not all of these examples are alike. In some cases, there are genuine political differences at stake. In others, the differences are more of emphasis than of substance, often exaggerated for petty point-scoring purposes.

Nevertheless, in all instances, for workers down below, these scuffles at the tops of the trade union movement will likely seem detached and divorced from their day-to-day struggles.

What is lacking across the labour movement is fighting leadership, willing to organise and mobilise members in pursuit of militant action and bold socialist policies.

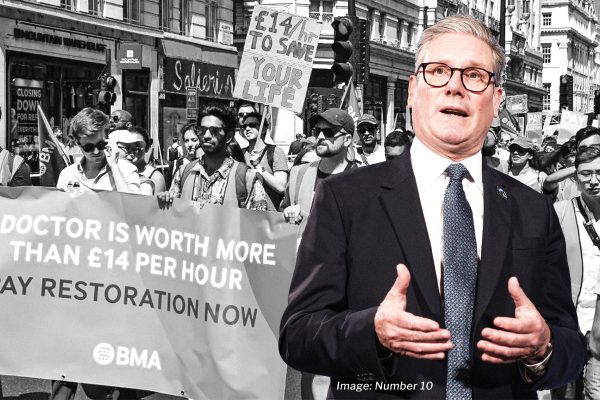

In advance of the general election, for example, all of the trade union leaders adopted a ‘wait for Labour’ attitude, helping to sow illusions in the idea that Starmer’s government would save workers from austerity and attacks like a knight in shining armour.

This was reinforced by July’s public sector pay deal, which the union leaders greeted with a sigh of relief, rather than with calls for rank-and-file members to remain vigilant.

At that time, Labour were keen to draw a line under the previous strike wave and put an end to any industrial disruption. With the deepening crisis of British capitalism, however, Starmer and co. have openly passed over to cuts, paving the way for a return of picket lines and walkouts.

Are the trade union leaders seriously preparing for such a perspective? Or are they paralysing the movement by focussing on internal battles?

Fighting leadership

If the working class is to defend itself, it needs organisation. Without this, as Marx once put it, workers are only “raw material for exploitation”.

Instead of short-termist squabbling over who gets to enjoy the perks and privileges of the top jobs, a trade union leadership worthy of the name would be using all the resources at its disposal to ready the rank and file for the impending class war.

Such a leadership would clearly explain the capitalist interests that this big business government represents – and, in turn, why the trade union movement cannot place any faith in Starmer’s Labour. Instead, workers must trust only in themselves; in their own strength.

Most importantly, a truly fighting leadership would explain the need for all the unions to join together in a coordinated, militant campaign for clear socialist policies.

Unfortunately, this kind of determined leadership is precisely what the workers’ movement lacks. It must therefore be built. And that is what the communists of the RCP are endeavouring to accomplish.