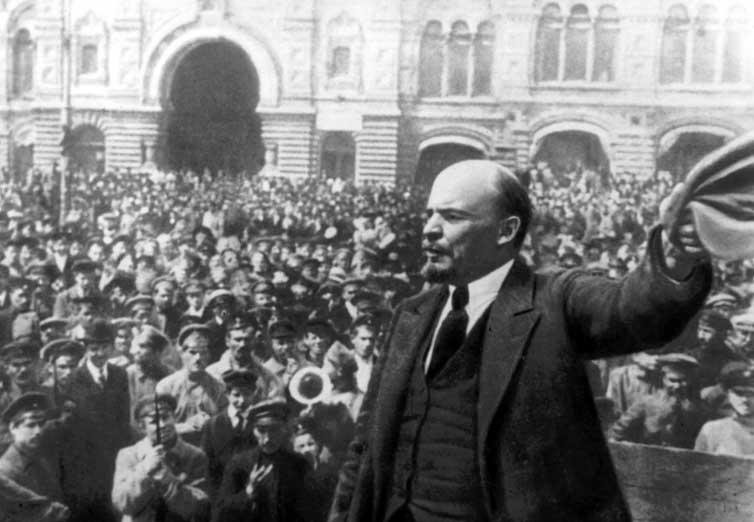

“We shall now proceed to construct the socialist order!”

These were the first words of Lenin to the Second All-Russian Congress of the Soviets, following the success of the workers’ insurrection in Petrograd on 8th November 1917. The socialist revolution had only just begun; the tasks ahead were to be immense.

The Bolsheviks were well aware that the revolution would be met by the full resistance of the landlords and capitalists. All means would be utilised to overthrow workers’ power – from economic sabotage, to out-and-out war.

It was therefore vital to win over the broadest mass of workers and peasants to the side of Soviet power, by proving to them in practice that this was a government that stood for their interests and hence worth fighting for.

Lenin wasted no time in drafting numerous appeals and decrees to put into effect the Bolshevik’s programme. These were to be published in their millions and distributed throughout the country by propagandists sent to all corners.

Lenin understood that a revolution couldn’t be decreed from above. Above all though, Lenin understood the propagandistic value of the decrees, by setting into law the framework for the transition towards socialism and explicitly calling for the masses to take their implementation into their own hands. In this way, Lenin sought to explain what the revolution stood for and enlist the broadest layers to its realisation.

All power to the Soviets!

On the day of taking power, the Congress of Soviets adopted its first appeal: “To the Workers, Soldiers, and Peasants!” This announced the overthrow of the Provisional Government and decreed that all power in the localities should pass to the Soviets of Workers, Soldiers and Peasant Deputies.

On the day of taking power, the Congress of Soviets adopted its first appeal: “To the Workers, Soldiers, and Peasants!” This announced the overthrow of the Provisional Government and decreed that all power in the localities should pass to the Soviets of Workers, Soldiers and Peasant Deputies.

The appeal summarised in one simple paragraph the programme of the Bolsheviks:

“The Soviet government will propose an immediate democratic peace to all the nations and an immediate armistice on all fronts. It will secure the transfer of the land of the landed proprietors, the crown and the monasteries to the peasant committees without compensation; it will protect the rights of the soldiers by introducing complete democracy in the army; it will establish workers’ control over production; it will ensure the convocation of the Constituent Assembly at the time appointed; it will see to it that bread is supplied to the cities and prime necessities to the villages; it will guarantee all the nations inhabiting Russia the genuine right to self-determination.”

It was made clear that this programme could only be implemented if the revolution was victorious. It ended: “Soldiers, workers in factory and office, the fate of the revolution and the fate of the democratic peace is in your hands!”

Peace

True to their word, the first act of the Soviet power was to issue the Decree on Peace, which called for immediate peace negotiations, on the basis of the self-determination of all peoples. The decree announced that the government would end secret diplomacy, publish the Tsarist secret treaties and call an immediate armistice.

True to their word, the first act of the Soviet power was to issue the Decree on Peace, which called for immediate peace negotiations, on the basis of the self-determination of all peoples. The decree announced that the government would end secret diplomacy, publish the Tsarist secret treaties and call an immediate armistice.

The Decree on Peace was significant in that it delivered immediately in deed, what the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries (‘SRs’), during their control of the soviets, had only promised for months. The millions of war weary workers and peasants knew that the Bolsheviks meant action.

Significantly, the decree was specifically addressed to the class-conscious workers of Britain, France and Germany, as well as their governments. In doing so, the Bolsheviks helped expose the imperialist ambitions of their respective ruling classes (who were against peace), and helped foment the growing revolutionary mood worldwide.

Land

“Landed proprietorship is abolished forthwith without any compensation.”

So began the Decree on Land, which was also passed on the first day of Soviet power.

The SRs, the traditional party of the peasants, had promised the end of landlordism when they assumed power in the February revolution. However, along with the Mensheviks, they entered into a coalition government with the landlords and capitalists. Hence they continually postponed any resolution to the land question into the indefinite future.

The result was a developing peasant revolt. Peasants in many areas took matters into their own hands, only to face suppression by the same Provisional Government, as backed by the SRs.

With the working class a small minority in Russia, the socialist revolution could only triumph if supported by the mass of poor peasants. Hence, the Bolsheviks adopted the SR programme on land reform, and reproduced it verbatim in the Decree on Land, despite having their differences with it. By uniting the interests of the poor peasants with the working class, the basis of support for the counter-revolution was enormously weakened.

In addition to giving land to the peasants, measures were taken to immediately address the chronic housing crisis in the cities. An Act “Concerning Dwelling Places” gave municipal self-governments the power to sequestrate all unoccupied dwelling places, and allocate them to those in need.

Thus from the first days of the revolution, the poorest understood that this was their government, one which was unafraid to take action against the interests of the rich.

Defend the Soviet Power

Despite taking power in Petrograd, the victory of the revolution was by no means assured. Understanding the danger of armed counter-revolution, the Bolsheviks issued a decree on 10th November, that “all Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies shall form a Workers’ Militia”. This led to the strengthening of the Red Guards across the country, which had played a vital role in the Petrograd insurrection.

Despite taking power in Petrograd, the victory of the revolution was by no means assured. Understanding the danger of armed counter-revolution, the Bolsheviks issued a decree on 10th November, that “all Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies shall form a Workers’ Militia”. This led to the strengthening of the Red Guards across the country, which had played a vital role in the Petrograd insurrection.

The importance of this was demonstrated clearly the next day. Red Guard detachments and revolutionary sailors easily put down a counter-revolutionary attempt at insurrection by students at the junker school in Petrograd.

Even more significant was the attempt by Kerensky (former head of the deposed Provisional Government) to march on Petrograd with several thousand Cossacks. With the aid of General Krasnov, the Cossacks had captured several towns on the edge of Petrograd by the 10th, since the revolutionary forces lacked supplies.

With the enemy near the gates, the Petrograd Soviet ordered all ward soviets and factory committees to organise the greatest number of workers for the digging of trenches, and supply the Red Guards. It was explained that all the conquests of the revolution were at stake and only their self-sacrifice could save it. Tens of thousands heeded the call, working night and day to bolster the defences.

With the Red Guard in the front lines, the Cossack army was defeated on the plains outside Petrograd on the night of the 12-13th. Kerensky, having lost all authority, gave up his ambitions and fled.

Following Kerensky’s defeat, all hopes of an immediate military victory for the counter-revolution were put to one side. From then, until the intervention of world imperialism in 1918, the strategy of the capitalists would be to attempt to bring down the Bolsheviks by means of economic sabotage.

Workers’ Control

From the moment of the insurrection in Petrograd, the higher up officials in all the governmental institutions refused to serve the new Soviet power. The tops of the Railway Union, the Post and Telegraph Unions, and the Union of Government Employees, all came out against the Bolsheviks. They implored their members to strike, refuse to transport revolutionary troops, or connect the revolutionary HQ with the rest of the country.

Combined with this, the capitalists attempted to starve the revolution, by stockpiling food, supplies and fuel, and closing down factories. The State Bank employees refused to open the vaults, except to pay out counter-revolutionaries. In order to combat this disruption, the Bolsheviks appealed directly to the rank-and-file workers to organise production and distribution, and hold saboteurs to account through revolutionary tribunals.

Workers Control in all enterprises was decreed on 27th November, and all the banks nationalised a month later. In addition, groups of Red Guards were sent to inspect warehouses, uncover hoarding, and obtain food from the countryside. In this way, a new state power was developed, based on the participation of the widest layers of workers and poor peasants.

Although there would be many difficulties, the resistance of the old exploiters was overcome, since millions of the downtrodden understood that this was their revolution, and the gains were worth fighting for.

Democracy

As well as consolidating power, negotiating peace and averting economic ruin, the Bolsheviks quickly enacted various democratic reforms that the February Revolution had failed to solve.

Within the first few days of the October Revolution, the Soviet government published the Declaration of the Rights of the Peoples of Russia, which included “the right of the peoples of Russia to free self-determination”.

These were not empty promises; as soon as 31st December, independence was granted to Finland at the request of the their government. In this way, the various nationalities of Russia, formerly oppressed under the Tsar, were brought closer together. It was clear that their union was voluntary.

Other decrees soon followed which provided for: the abolition of social estates and civil ranks (23rd November), the right of recall of elected representatives (6th December), the separation of the church and state (24th and 31st December, 23rd January) and equal rights for women to divorce (29th December). Most of these measures are absent in even the most “democratic” bourgeois states today!

Construct the Socialist Order

The legislative work of the first few months of Soviet power gives a glimpse into the aims and depth of the world’s first socialist revolution. Not all their decrees could be fully implemented, since the Soviets lacked the necessary resources and state apparatus to do so.

The legislative work of the first few months of Soviet power gives a glimpse into the aims and depth of the world’s first socialist revolution. Not all their decrees could be fully implemented, since the Soviets lacked the necessary resources and state apparatus to do so.

Nevertheless, the propaganda effect of the decrees was enormous, both in Russia and internationally. They played a significant factor in mobilising the forces of millions to construct and fight for the new workers’ state (particularly during the Civil War) and spread revolutionary ideas worldwide.

Unlike the Bolsheviks, who had no precedent to follow, Marxists today can learn enormously from the first successful attempt of the working class to take power and transform society. Although every revolution will contain its own particular set of obstacles, the decrees implemented by the Bolsheviks in their first year of power serve as a rich resource for revolutionaries around the world today.