Most of us take it for granted that when we turn on a tap we have access to

safe and clean water to drink, to cook and to wash. However, 20% of the world's

population, over a billion people, lack access to safe drinking water and about

2.6 billion people – 40% – have no access to basic sanitation.

The issue of water is one of the largest public health issues but access to

water is primarily a class issue. Without question, the world water crisis

condemns billions of people to a perpetual struggle to survive at the

subsistence level – millions are living on less than $1 a day. A third of the

world's population lives in "water stressed" countries (i.e. where

water is scarce or of poor quality) and that number is expected to rise

dramatically over the next two decades.

Some countries have additional problems, including high levels of arsenic and

fluoride in drinking water. Many women and young girls in rural areas around

world must walk as much as six miles everyday to fetch water for their

families. Due to this manual labour, women and children are prevented from

pursuing an education or earning an income.

Yet lack of access to water and sanitation is not just a rural issue. In

2007, for the first time in history, the majority of people will live in urban

areas. Even the UN admits this will result in larger slum populations in

sub-Saharan Africa and Asia and these new city residents face overcrowding,

inadequate housing, and a lack of water and sanitation.

Not being able to access sanitation and safe water contributes to increased

poverty, poorer health and high levels of child deaths. In 2004, 2.2 million

people died from drinking unsafe water, of which about 90% were children under

the age of 5 (UNICEF/WHO 2005). Unsafe water is estimated to kill 4,500

children per day, mostly a result of diarrhoeal diseases – far more than are

killed by Malaria and AIDS combined. It is equivalent to 25 fully loaded jumbo

jets crashing every day!

Preventable deaths

These deaths are easily preventable. Under capitalism, however, water is

only an issue when it can guarantee large profits. Look no further than the

privatisation of water in the UK

where last year a host of private water companies declared massive increases in

profits. Thames Water had a 31% increase in profits despite admitting that it

had missed its leak reduction target for a third successive year (The Daily

Telegraph, 22.6.06) and Severn Trent announced a 30% rise in profits to

£400m despite being under criminal investigations by the Serious Fraud Office

over false reporting – this figure would have been higher but for the £10.6m it

was ordered to pay back to customers. Other profit increases reported included

United Utilities who had a 21% rise in profits to £481m; Pennon saw profits

rise by 25% to £111m and Anglian Water owner AWG announced that annual profits

had trebled to £109m. (BBC 7.6.06) These massive profits even led the British

TV programme Panorama to ask whether the water industry should be

renationalised.

The world's financial markets are in no doubt about the benefits to big

business of water privatisation, prompting one money magazine to run a feature

on, How to profit from the world's water crisis. It boasts:

"Overall, the ‘scramble for water assets' has now seen bidders put

almost £12bn on the table, says The Daily Telegraph. But the buying frenzy

isn't over yet. The losers in these auctions may well be tempted to bid for one

of the several other UK

water companies, which are ‘ripe for takeover'. United Utilities, Severn Trent,

Northumbrian Water, Kelda – the former Yorkshire Water – and Pennon, the owner

of South West Water, are all seen as potential targets. As a result, their

shares have soared by up to 50% over the past year." (Money Week,

19.10.06)

They continue, "So what makes utilities look so good to bidders? The

reliability of the returns they offer. The system of economic regulation

imposed by Ofwat offers known rates of return over five-year pricing cycles,

which is attractive to private equity and infrastructure funds…. The problem

here is that this is just about the only thing that makes the water utilities

attractive and bidding presupposes that Ofwat keeps playing along… there are

still plenty of opportunities for investors. The profits will come from

companies that help nations improve the water that they already have." (Money

Week, 19.10.06)

Some years ago vice-president of the World Bank, Ismail Serageldin, said

that the wars of the 21st century would be about water. Soon after this, the

World Bank adopted a policy of water privatisation and full-cost water pricing.

This certainly caused a war – a class war – in Bolivia's

third largest city, Cochabamba.

Their struggle proved that the privatisation of water can be fought.

Cochabamba

In the late 1990s the World Bank refused to guarantee a US$25million loan to

refinance water services in Cochabamba

unless the government sold the public water system to the private sector and

passed the costs on to consumers. Only one bid was considered and the utility

was turned over to a subsidiary of a conglomerate led by Bechtel, the giant

engineering company implicated in the infamous Three Gorges Dam in China (which

has caused the forced relocation of 1.3 million people). Interestingly at that

time, a World Bank official attended Bolivian government cabinet meetings as a

full participant.

In January 2000, the private company announced the doubling of water prices.

In a country where the minimum wage was less than US$70 per month, many people

were hit with monthly water bills of $20 or more. For most Bolivians, this

meant that water would now cost more than food; for those on a minimum wage or

unemployed, water bills suddenly accounted for close to half their monthly

budgets. To turn the screw even further, the World Bank granted monopolies to

private water concessions, announced its support for full-cost water pricing

and pegged the cost of water to the American dollar. It also declared that none

of its loan could be used to subsidise water services for those living in

poverty.

Permits to access

All water, even from community wells, required permits to access, and

peasants and small farmers even had to buy permits to gather rainwater on their

property. This followed similar attacks in La Paz

(the capital of Bolivia)

and El Alto when the World Bank made privatisation of water a condition of a

loan to the Bolivian government. The private consortium that took control of

the water, Aguas del Illimani, was owned jointly by the French water giant, Suez, and a set of

shareholders that included an arm of the World Bank.

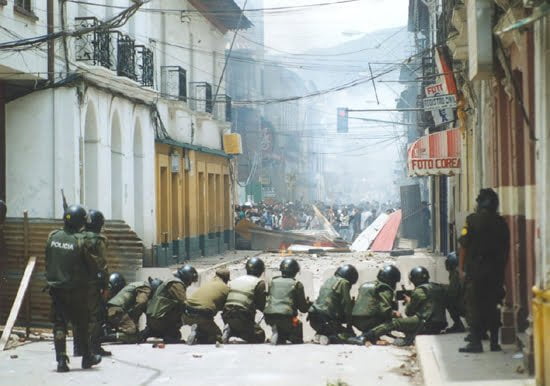

The population of Cochabamba

responded with a general strike which shut down their city for four days. This

was led by workers, peasants and community leaders. The government, led by

President Banzar (a dictator for most of the 1970s), was forced to the

negotiating table with the promise of a reduction in the price and an agreement

to work out the details in two weeks. The general strike was halted but a month

later still no agreement had been agreed. On 4 February 2004 thousands

attempted to march in Cochabamba

but the President turned once again to the use of violent repression. He called

out the police, who engulfed marchers for two days, leaving six people dead and

175 injured, including two children blinded.

But the workers and peasants of Cochabamba

did not back down. In a survey of more than 60,000 residents in March, 90% said

that private company must leave and the water system returned to public

ownership. They pointed to the privatisation of water in Buenos Aires where 7,500 workers were fired

and prices rose, as an example of why they felt privatisation had to be

opposed.

Demonstrations

Another general strike was called on 4 April, again closing down the city.

Blockades cut off the main highway and protestors occupied the city centre.

Four days into the demonstrations, the government declared martial law. Police arrested

the strike leaders, taking them from their beds in the middle of the night and

charging them with sedition, shutting down radio stations in mid-broadcast.

This attempt at repression simply served to spur the movement to new heights.

The strike leaders were released after four hours and the daily strike

meetings in the central plaza more than doubled to 40,000. The water company

officials tried to claim that the protests were riots sponsored by cocaine

producers against a crackdown on coca production. However, the might of Cochabamba finally forced

the government to concede on 10 April – signing an agreement that agreed to all

the demonstrators' demands.

Cochabamba's water supply is now run by a local water board with

workers' participation as a minority on this board. Marxists are critical about

many aspects of the campaign by the Coordinadora (the Coalition in Defence of

Water and Life) such as why the movement was not generalised and linked up with

other struggles nationally, and settling for workers' participation rather than

workers' management of the local water board. However, there are many positive

lessons, notably the ability and willingness of the Coordinadora to lead a

city-wide insurrection to halt privatisation. This will have a lasting effect,

not only in preventing Bechtel from getting their greedy hands on Cochabamba's

water supply, but crucially in giving confidence to workers and peasants in

Cochabamba in their own strength.