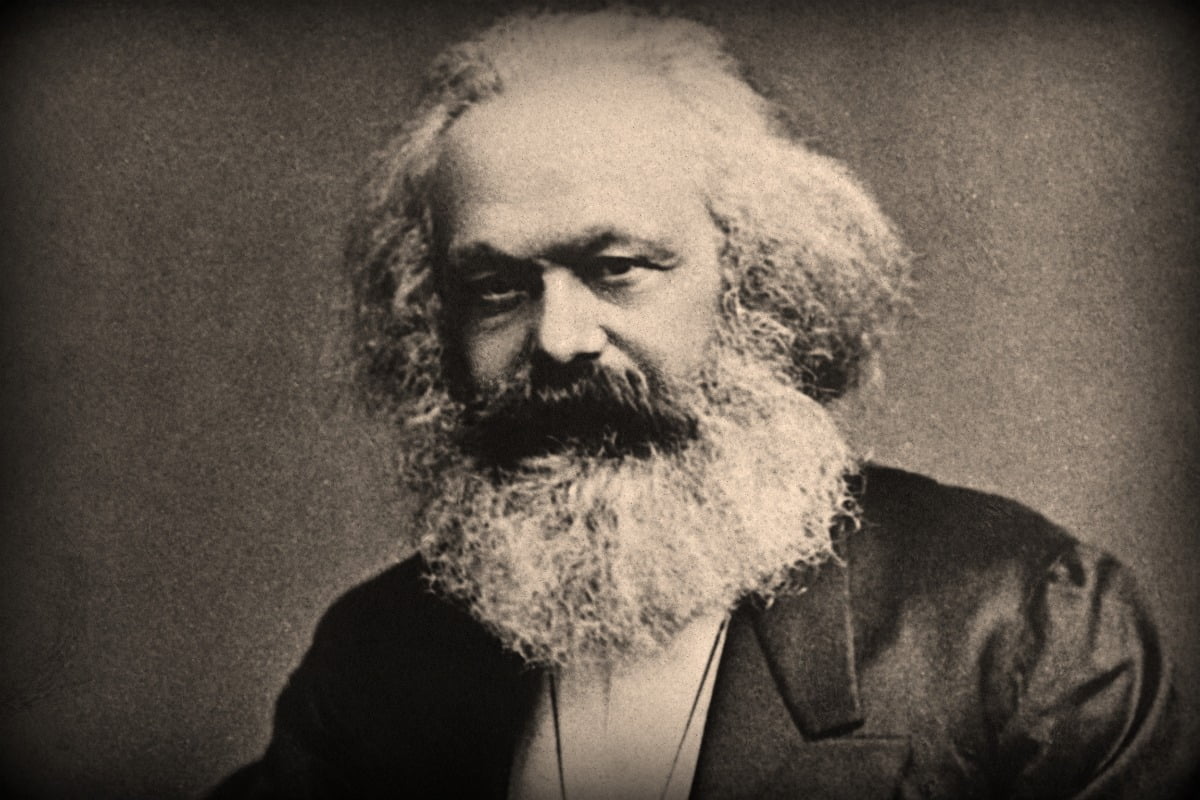

Value, Price and Profit was delivered by Marx as a series of lectures to meetings of the General Council of the International Working Men’s Association (the First International) on 20 and 27 June 1865, while Marx was preparing the first volume of Capital.

At the meeting of the General Council on 4 April 1865, John Weston, a member of the General Council, a representative of the English workers and a follower of Robert Owen, proposed that the Council should discuss two questions: first, the question of whether or not an increase in wages will improve, in general, the material conditions of the working class and, second, whether or not wage increases in one branch of industry will have a detrimental impact on other branches of industry. Weston delivered a report on these questions to meetings of the General Council on 2 and 20 May 1865, in which he argued that an increase in wages will not improve the material conditions of the working class and that trade union organisation, because of its harmful impact on industry, is detrimental to the material interests of the working class. In the meeting on 20 May, Marx argued against Weston’s conclusions, and the meeting agreed that Marx would deliver a full counter-report, on 20 June, and that the reports of both Weston and Marx would be published.

Weston’s arguments were based on the acceptance of the theory of a wages fund – that is, a fixed amount of capital from which capitalists pay the wages of workers. The implication of this theory is that attempts, by the workers, to increase money wages will be ineffectual because capitalists will respond, either by raising the prices of necessities (thereby bringing real wages back to their previous level) or by reducing the number of workers employed. Hence, the theory was a weapon in the hands of the bourgeoisie in their efforts to resist the economic struggles of the proletariat; and, of course, if workers were not to participate in an economic struggle, they would not understand the need for a political as well as an economic struggle to overthrow capitalism. In short, the implication of this theory, which Marx understood well, was that the class of wage-labourers should be subservient to the class of capitalists. It was for this reason that Marx felt compelled to rebut Weston’s claims and that he argued in support of the economic struggle of the workers. However, Marx explained that this type of struggle is a means to an economic and a political end: the abolition of capitalism and the rule of the working class.

Marx’s report to the General Council was not published in his lifetime: the manuscript was found among his papers after the death of Engels, and was prepared for publication in 1898 by his daughter, Eleanor, and her husband, Edward Aveling.[1] The latter added a preface to the text and re-organised it by inserting headings for the introduction and for the first six chapters.

The two parts of the original text correspond to Chapters 1 to 5 and Chapters 6 to 14 of the English edition of 1898. In the first part, Marx identifies the mistaken assumptions in Weston’s reasoning while, in the second half, in further development of his critique of Weston’s views, Marx gives us a clear and concise exposition of the labour theory of value, the relationship between wages and profits, and the nature and lessons of the struggle between capitalists and wage-labourers (amongst other things). It is for this reason that this text is often recommended as an introduction to the first volume of Capital, in which the labour theory of value is given more extensive treatment. However, the fact that Marx presented this theory so clearly and concisely in Value, Price and Profit is a considerable achievement, given his view, which he expressed in a letter to Engels of 20 May 1865, that a “course of political economy” cannot be compressed “into one hour.”

In this study guide, we follow the text of the English edition of 1898.

Preliminary

By way of an introduction to the main parts of the text, Marx makes two preliminary remarks, both of which may be understood as pointing to the necessity for a leadership of the working class that is unified and theoretically well-informed. If the leadership lacks unity (“settled convictions”) on the questions before it – such as whether or not to support striking workers’ “clamour for a rise of wages”– or if it is unified but theoretically misinformed and makes practical mistakes in consequence (for example, by calling on striking workers not to demand higher wages), rank-and-file workers will lose confidence in it – a loss which, if not repaired, will become an impediment to the further development of the class struggle.

I. Production and Wages

Marx begins by calling into question the two related premises on which Citizen Weston’s argument depended: that the quantity of national production and the real value of wages are fixed.

The quantity of national production cannot be fixed, Marx tells us, because production statistics demonstrate that both the “value and mass of production” change from year to year. If there is an expansion in the scale of production, from one year to the next, both the value of production (the total quantity of labour that is embodied in what is produced) and the mass of production (the total number of commodities that are produced) increase (other things being equal); and if production becomes more efficient, because productivity has increased, the total number of commodities that are produced, within a year, increases but the value of each one decreases, because each one is produced with a smaller amount of labour (other things being equal). Moreover, it is because the value of production changes from year to year that the supply of money changes from year to year because money is needed to facilitate the circulation of exchange value throughout the economy.

However, even if the quantity of the national product were fixed, Marx argues, it does not follow that real wages would be fixed because the wage, which is one share of the value that the worker generates, is inversely related to another share of the value that the worker generates – that is, profit. In other words, if production is to be profitable, capitalists must ensure a continual reduction in the value of the real wage (or the value of goods and services that the nominal wage can command in exchange).[2]

What all this means is that capitalist production is a question, not only of economics – of producing as efficiently as possible – but also of politics – of the power that one class in society – the capitalist class – has over another class in society – the working class.

Questions for discussion

- How does the value and mass of national production change, when the scale of production changes?

- How does the value and mass of national production change, when the productive power of labour changes?

- Why does John Weston assume that the real value of wages is fixed?

- Why can we not assume that the real value of wages is fixed?

II. Production, Wages, Profits

At the start of this chapter, Marx states, concisely, one of the economic implications of Citizen Weston’s assumption that the quantity of the national product is fixed: that is, if the working class secures an increase in money wages, the capitalist class will respond by increasing the prices of other commodities, with the result that the real value of the wage (the quantity of goods and services that workers can command in exchange) will stay the same.

Marx reminds us that Citizen Weston’s argument assumes that “the amount of wages is fixed.” Such an assumption is problematic, Marx argues, because it begs the question which quantity of wages is the one that is fixed. To avoid this problem, Citizen Weston must show that the amount that is fixed is governed “by an economical law”; and, if he cannot establish this fact, his argument will be arbitrary – that is, the amount of wages that is fixed will be the consequence of “the mere will of the capitalist, or the limits of his avarice”.

Marx points out the capitalists cannot simply raise prices at their will, because they are subject to the pressures of supply and demand.

Consider the production of necessities. Following an increase in wages, the market price of necessities will increase because, if workers spend their wages on necessities, the demand for necessities will increase, relative to their supply; and capitalists who produce necessities will be able to maintain their rate of profit because the increase in the market price will compensate them for the increased wages they must pay.

By contrast, because the demand for luxuries will not increase, the market price of luxuries will not increase, with the result that the rate of profit for those capitalists who produce luxuries will start to decrease.

The consequence of the increase in the wage, then, is a difference in the average rate of profit between the two spheres of production. Capital will flow from the sector in which luxuries are produced (the less profitable sector), to the sector in which necessities are produced (the more profitable sector), until the increase in the supply of necessities has eliminated the excess demand for them and until the decrease in the supply of luxuries has eliminated the excess supply of them; and, consequently, until the market prices of necessities fall and the market prices of luxuries rise.

The end result is an average rate of profit that is now equal, across both spheres of production – but an average rate of profit that is now lower than it was before the increase in the wage. Moreover, although the total quantity of the national product and the productivity of the economy will not have changed, the relative content of the national product will have changed because of the expansion in the supply of necessities and the reduction in the supply of luxuries.

Marx then adduces the consequences of the rise in wages in Great Britain, between 1849 and 1859 in support of his argument. Marx tells us that, contrary to what the bourgeois economists predicted (that is, economic ruin), the prices of commodities actually fell during this period – alongside the rise in the wages of the factory workers and the shortening of the working day that was the consequence of the Ten Hours Bill – because productivity increased. (When productivity increases, the labour time required to produce commodities, and hence their exchange value, decreases.) Marx also gives the example of rises in wages for agricultural workers alongside falls in the price of wheat.

Questions for discussion

- What is problematic about assuming that a certain amount of wages is fixed?

- Why is it problematic to assume that capitalists will respond to an increase in wages with an increase in the prices of commodities?

- How does the historical evidence contradict John Weston’s argument about the relationship between wages and other commodity prices?

III. Wages and Currency

In this chapter, Marx addresses the assumption that the amount of money in circulation is fixed, an assumption which follows from the initial assumption that the quantity of the national product is fixed. It is a problem for John Weston’s argument, because if the amount of money in circulation is fixed, an increase in wages cannot be paid; yet, in making his argument, Weston assumes that payment of an increase in wages is possible.

Marx calls into question, once again, the claim to which the assumption of a fixed supply of money is related and which he has already rebutted: that a rise in wages leads to a rise in the prices of necessities. Marx shows us, once again, that the facts contradict this claim. In the early 1860s, for example, as the degree of international competition in the cotton industry intensified, the wages of cotton operatives in England decreased by about 75 per cent. However, over the same time period, the price of wheat (a major ingredient for the supply of basic food) increased: that is, the average price of wheat for the years 1861 to 1863 was higher than its average price for the years 1858 to 1860. In short, the historical evidence does not support Weston’s claim that a rise in wages leads to a rise in the prices of necessities.

Marx then observes that, despite the vast increase in monetary transactions in the railway industry in England between 1842 and 1862, the total amount of money in circulation stayed roughly the same; indeed, he points out that there is a tendency for the amount of money in circulation to diminish as the amount of exchange value that is generated increases. In short, the historical evidence does not validate Weston’s assumption that the amount of money in circulation is fixed.

We can explain all these facts, Marx argues, once we understand that there is variation, each day, in the “amount of monetary transactions to be settled”; in the forms of money that are used to facilitate these transactions; in the amount of money that is held by banks in reserve; and in the amount of money that is in circulation, both nationally and internationally.

In short, given all the evidence before us, we cannot assume that the amount of money in circulation is fixed.

Questions for discussion

- What is the problem, for John Weston’s argument, with assuming that the amount of money in circulation is fixed?

- What evidence is there that indicates that the amount of money in circulation is not fixed?

- What is the relationship between the velocity of circulation of money and the supply of money?

- What is the relationship between the supply of money and the amount of exchange value that is generated?

IV. Supply and Demand

In this short chapter, Marx addresses the problem that Citizen Weston, or anyone else, faces, when they say that wages are too high or too low. The problem with this sort of claim, Marx argues, is one of reference: how can we say that wages are too high or too low, if we do not refer to “a standard by which to measure their magnitudes”?

Now, in the case of the movement of wages, that standard will be the exchange value of labour power, whose monetary expression is its price, or wage.

But what determines its exchange value: the laws of the labour market – by the supply of, and the demand for, labour power? Marx argues that it is not: he maintains that the laws of the labour market dictate “nothing but the temporary fluctuations of market prices.” Thus,

- when we say that wages are too high, we mean to say that the market price of labour power is greater than its exchange value, because the demand for labour power is greater than its supply;

- when we say that wages are too low, we mean to say that the market price of labour power is less than its exchange value, because the demand for labour power is less than its supply;

- when we say that wages are neither too high nor too low, we mean to say that the market price of labour power is equal to its exchange value, because the demand for labour power is equal to its supply.

However, in each case, the question of the determination of the exchange value of labour power – of the wage standard or point of reference – remains unanswered.

This is a question that Marx addresses in subsequent chapters.

Questions for discussion

- How can we avoid the problem that arises when we say that wages are either too low or too high?

- In what circumstance will the market price of labour power be less than the exchange value of labour power?

- In what circumstance will the market price of labour power be greater than the exchange value of labour power?

- In what circumstance will the market price of labour power be equal to the exchange value of labour power?

V. Wages and Prices

In this chapter, Marx lays to rest the “old popular, and worn-out fallacy that ‘wages determine prices’”.

If this claim were true, Marx suggests, low prices of commodities would be associated with a low price of labour power, and, vice versa, high prices of commodities would be associated with a high price of labour power. However, the opposite is the case: “high-priced labour [power]” is associated with “low-priced” commodities, and, vice versa, “low-priced labour [power]” is associated with “high-priced commodities”.

Given that the wage is the price of labour power and that the price of any commodity (including labour power) is the monetary expression of its exchange value, to say that wages determine the price of commodities is just to say that the value of labour power determines the value of commodities. But that begs the question: what determines the value of labour power? Citizen Weston and other proponents of a components theory of price cannot answer this question, Marx tells us, because their answer must be circular in its reasoning.

This problem – of circular reasoning – is the problem that we encounter, when we make any commodity “the general measure and regulator of value”: we end up saying that the value of one commodity is what it is because it is equal to the value of another commodity, and thus we avoid understanding how exchange value is generated.

Marx concludes that, to accept the “dogma” that “‘value is determined by value’” is to accept a “tautology”.

Questions for discussion

- How does the historical evidence contradict the claim that the price of labour power determines the prices of other commodities?

- What is the consequence of making a commodity the measure of exchange value?

VI. Value and Labour

Having addressed the mistakes in Citizen Weston’s argument, Marx turns to the nature of value and asks us to consider what the value of a commodity is and how this value is determined.

When we consider the exchange value of any commodity, Marx tells us, we have to make sense of the fact that a certain quantity of one commodity (for example, a quarter of wheat) may be exchanged for different quantities of other commodities (for example, cotton or iron); and to make sense of this fact, Marx asks us to think about what determines the variations in the quantities that are exchanged.

The answer to this question, Marx argues, is the quantity of labour that is embodied in each commodity – the “realized, fixed, or … crystallized social labour” – which is measured by time. The longer is the time for the production of a commodity, the higher is its value; the shorter the time, the lower its value.

Moreover, when we consider what determines the exchange value of any commodity, we must also take into account the quantity of labour that is embodied in the raw materials, tools and other means of production – a value that is transferred, gradually, to the finished goods and services during production. The gradual transfer of value – the “average waste or wear and tear during a certain period” – is known as the rate of depreciation.

Furthermore, the quantity of labour by which the exchange value of any commodity is determined is the quantity of labour that is socially necessary – what Marx refers to simply as “social labour” – because to speak of a commodity, as opposed to just a product of labour, is to presuppose social relations of contract, hierarchy, private ownership, etc. – in short, all the different social relations that constitute the capitalist system of production.

The socially necessary labour time that determines the exchange value of any commodity must be the socially necessary labour time on average. In this way, we take into account differences, not only in the natural conditions of production – “such as fertility of soil, mines, and so forth” – but also differences in the intensity of the labour, the skill of the labourers, the extent of the division of labour, the technology employed, the degree of mechanisation of production, the ease of communication and transportation, and so on.

Productivity, then, is a property of a system of production; as such, it is another type of social property. This is why, in his discussion of the determinants of productivity, Marx also uses the phrase “the social powers of labour”.

In the final part of this chapter, Marx discusses the “monetary expression of value” or price. When we assign a price to a commodity, Marx tells us, we reveal the quantity of social labour that is embodied within it; and, moreover, we do this homogeneously – by using money as our means of expressing the exchange value of each commodity – so that we can compare, easily, the exchange values of different commodities.

Because goods and services are exchanged for money in the market, we have to distinguish between the natural price of a commodity and its market price. If the supply of a commodity is equal to the demand for it, its market price will be the same as its natural price. However,

- if the supply of a commodity exceeds the demand for it, its market price will tend to fall below its natural price;

- if the demand for a commodity exceeds its supply, its market price will tend to rise above its natural price.

In the long run, though, a rise in the market price is compensated by a fall, and vice versa, so that, on average, a commodity is always sold at its natural price or at its exchange value. What this means, Marx tells us, is that the existence of profit cannot be explained by the selling of a commodity at a price that is above its exchange value (what is known as surcharging).

Questions for discussion

- What is the exchange value of a commodity?

- What is the relationship between the value of the labour power that is employed to produce a commodity and the exchange value of that commodity?

- What is depreciation?

- Why do we measure the exchange value of a commodity by the quantity of labour that is socially necessary, on average, for its production?

- What is the difference between natural price of a commodity and its market price?

- Why can we not explain the existence of profit via the concept of surcharging?

VII. Labour Power

From consideration of the determination of the exchange value of commodities, Marx turns to the concept of labour and asks us to consider the meaning of the expression the “value of labour”. It is common sense, Marx tells us, that labour is a commodity just like anything else that is bought and sold. But common sense is wrong: “there exists no such thing as the value of labour in the common acceptance of the word.”

Labour is the process through which exchange value is generated. Now, it is because labour occurs through time that labour time is the appropriate measure of exchange value. Therefore, if we were to ask what determines the exchange value of a unit of labour, our answer would have to be circular in its reasoning and thus “nonsensical”. We know that it is the quantity of (socially necessary) labour that determines the exchange value of any commodity; yet, the unit of labour that we are treating as a commodity is itself labour time. This is like saying that £5 is worth £5.

We can now understand why it is a mistake to treat labour as a commodity and to try to work out what determines its value; the result is, in Marx’s words, an “irrational … application of value”. We can also understand why the phrase the “value of labour” is “tautological” because, to speak of the value of labour is to presuppose that value is a concept that is independent of the concept of labour.

Therefore, if it is a mistake to think of labour as a commodity, the correction to this mistake is to think of labour power as what is bought and sold. In the second half of the chapter, Marx considers what determines the exchange value of labour power. His answer, of course, is in accordance with his law of value: that it is the quantity of labour that is socially necessary, on average, to produce labour power that determines its value in exchange. How, though, is labour power produced? What are the costs of its production? There is the cost of maintaining one’s capacity to work through consumption of the necessities of life. But there is also the cost of educating and training workers to develop their knowledge and skills. Moreover, as workers become worn out and retire, there is the cost of replenishing the supply of labour power through the rearing of children, whose physical and intellectual development also depends on consumption of the necessities of life. In short, “the value of labouring power is determined by the value of the necessaries required to produce, develop, maintain, and perpetuate the labouring power.”

Note, furthermore, that some kinds of labour power are more costly to produce than others so that, across different industries, we see variation in the value of labour power and its price – the wage. It is, therefore, a mistake, Marx argues, to call for “an equality of wages” because, if “different kinds of labouring power have different values … they must fetch different prices in the labour market.” Marx suggests that underlying this call for equality is the desire for freedom from wage-slavery; but to call for such an equality is to take for granted the mode of production – capitalism – in which labour power is a commodity. To de-commodify labour power, it is necessary to abolish capitalism and the “wages system” on which it depends; that is the only way to emancipate the working class.

Questions for discussion

- What is labour?

- What is problematic about the expression ‘the value of labour’?

- What is labour power?

- How did labour power come to be a commodity?

- What determines the exchange value of labour power?

- Why is it a mistake to call for equal wages?

VIII. Production of Surplus Value

In this short chapter, Marx considers the origin of surplus value. Where does it come from? In answering this question, Marx begins by reminding us that the capitalist, when purchasing labour power, acquires “the right to consume or use” that power. In other words, by taking ownership of labour power, or the capacity to work, via the employment contract, the capitalist gains control over the exercise of that power.

Now, if it takes a person six hours, on average, to produce the daily necessities of life, six hours will be the quantity of necessary labour through which necessary value is realised as necessary produce. However, if the capitalist demands a working day of 12 hours, the worker will be producing a value that is greater than the value of the daily necessities of life. In this situation, there will be, in addition to the six hours of necessary labour, six hours of “surplus labour” through which “surplus value” is realised as “surplus produce”; and, because the capitalist is the owner of the labour power and the means of production, the capitalist takes possession of the whole product of the 12 hours of labour.

What all this means is that the exchange value of labour power, which “is determined by the quantity of labour necessary to maintain or reproduce it”, is distinct from the “use” or “exercise” of labour power, which is limited only by the physical and intellectual capacities of the labourer.

The origin of surplus value, therefore, lies in the unequal exchange between the capitalist and the labourer: the capitalist receives, from the exercise of labour power, a value of produce that is greater than the value of the labour power that the capitalist purchased, while the labourer receives, through the wage, a value that is less than the total value of what has been produced. “It is this sort of exchange,” Marx concludes, “upon which capitalistic production, or the wages system, is founded, and which must constantly result in reproducing the working man as working man, and the capitalist as a capitalist.”

Questions for discussion

- What is the use value of labour power?

- What are the limits to the exercise of labour power?

- What is surplus value?

- Which social relations are the conditions for the production of surplus value?

IX. Value of Labour

In another short chapter, Marx revisits the expression that he has called into question in a previous chapter: the “‘value, or price of labour.’” Marx considers how this expression becomes part of the common sense of the worker. He argues that, because workers think of themselves as working for a capitalist, receiving in return for their work a wage, they think of the value of the wage as being equal to the value of what they have produced for the capitalist. In this way, workers misunderstand the nature of their relation to the capitalist: the “value or price of the labouring power” appears to them as the “price or value of labour itself”, while the “unpaid labour” which they provide and through which they generate “surplus value or profit” for the capitalist appears to them as “paid labour.”

With each mode of production a specific form of labour is the basis for the exploitation of one class of people in society by another, whether the exploitation is achieved through slavery (in the ancient mode of production), serfdom (in the feudal mode of production) or employment (in the capitalist mode of production).

Questions for discussion

- What is it about slavery that makes us think that all the labour that slaves provide is unpaid?

- What is it about employment that makes us think that all the labour that employees provide is paid?

- What is it about serfdom that makes us think that serfs provide labour for their lord voluntarily?

X. Profit Is Made by Selling a Commodity at Its Value

In this short chapter, Marx asks how the capitalist makes a profit from production. His answer is quite simple: the capitalist makes a profit by selling the product of labour, not at a price that is greater than its (exchange) value (that is, through surcharging) but at a price that is equal to its value.

How is this possible? It is possible because the (exchange) value of a material object is equal to the “total quantity of labour” that is realised within it. Because this quantity of labour is a combination of “paid labour” and “unpaid labour”, when the capitalist sells the object at its value, the money received represents a value that is greater than the value of the labour power that was used in its production (the necessary value).

In short, by selling a product of labour at its value, a capitalist realises the surplus value that is embodied within it as profit.

Questions for discussion

- How does a capitalist make a profit from production?

- What is the cost of producing a commodity to a capitalist?

- What is the cost of producing a commodity to a wage-labourer?

XI. The Different Parts into Which Surplus Value Is Decomposed

In this chapter, Marx develops our understanding of the distribution of surplus value. He argues that, to the extent that the (industrial) capitalist does not own land, one part of the profit that is made from production must be paid as “rent”, to the owner of the land that is used as the site of production; a second part must be paid as “interest”, to the owner of the instruments of production (which will be a financial capitalist, if money is borrowed to cover the cost);[3] while a third part will be retained as “industrial or commercial profit”. In short, rent, interest and industrial profit are three different shares of the total surplus value that is embodied in the commodity.

Of course, to the extent that the industrial capitalist is the owner of the land, buildings and instruments of production (the tools, machines, etc.), the “whole surplus value” may be retained.

So far, Marx has divided the total (exchange) value of a commodity into necessary value and surplus value. However, a third part of the total value is the replacement value – that is, the value of the means of production that is used up as production proceeds. (The value of a machine, for example, is transferred, gradually, to the objects whose production the machine facilitates.) When the capitalist has sold all the commodities that can be produced to the point at which the means of production is worn out, the capitalist will use some of the proceeds from the sale of the product to cover the cost of replacing the means of production.

Leaving aside replacement value, Marx emphasises that rent, interest and industrial profit are not three different forms of surplus value, whose “addition” is equal to the total surplus value of a commodity. What he means by the “decomposition of a given value into three parts” is not “the formation of that value by the addition of three independent values”; rather, Marx means three different claims that may be made on the total surplus value, by virtue of the existence of different types of private ownership – of the land, of the instruments of production, and of the product of labour – that are all part of the capitalist system of production.

In the final part of the chapter, Marx distinguishes between the “amount of profit”, which is an absolute magnitude”, and the rate of profit, which is a “relative magnitude”. The latter is a relative number because it is the “ratio” of the total surplus value to the total value of the capital that is advanced in production, which comprises the value of the labour power (the wages) and the value of the raw materials, instruments and any other means of labour.

Taking £100 as the quantity of surplus value (s) and £500 as the quantity of the total capital advanced, and dividing the latter into the value of the labour power (v) and the value of the means of labour (c), we can express the rate of profit (r) as an equation:

r = s/(c+v) = £100/(£400+£100) = 1/5 x 100 = 20%

Questions for discussion

- What is the relationship between rent, interest and industrial profit, on the one hand and surplus value, on the other?

- What is the replacement value of a commodity?

- What is the difference between the amount of profit and the rate of profit?

- How can the capitalist increase the rate of profit?

XII. General Relation of Profits, Wages, and Prices

In this chapter, Marx considers how profits and wages, and value and price, are related.

When examining the relationship between profits and wages in the first half of the chapter, Marx asks us to exclude from consideration the replacement value of a commodity and focus on the value that the labourer has generated.

Marx tells us that wages and profits are inversely related. Expressing this relationship more precisely and remembering that we are excluding from consideration the replacement value, we may say that, if wages rise, the rate of profit must fall; whereas, if wages fall, the rate of profit must rise.

We can now understand, in part, the nature of the struggle that has ensued between the class of capitalists and the class of wage-labourers: it is, in part, a struggle over the division of the product of labour – a tug of war, if you like. That struggle can only be resolved through a revolution: through the class of wage-labourers taking ownership of the means of production and deciding, democratically, how to distribute the product of labour.

In the second half of the chapter, Marx considers the nature of the relationship between exchange value and price. He argues that, although the exchange value of a commodity is determined by the labour time that is embodied within it, this value is not fixed: it will change, as the “productive power of the labour employed” changes.

- the greater the productive power of labour, the larger the number of commodities that are produced within the given time period, the smaller the quantity of labour that is embodied in each one, and the lower the price of each one;

- the lesser the productive power of labour, the smaller the number of commodities that are produced within the given time period, the larger the quantity of labour that is embodied in each one, and the higher the price.

Questions for discussion

- Why is there a struggle between capitalists and wage-labourers over the distribution of the product of labour?

- What is the relationship between the productive power of labour and the natural price of a commodity?

XIII. Main Cases of Attempts at Raising Wages or Resisting Their Fall

In one of the longest chapters, Marx examines, via four different scenarios, the different factors that drive workers to demand an increase, or resist a decrease, in wages.

In the first scenario, Marx considers the impact of a change in the value of necessities on the worker’s standard of living.

- If the value of necessities were to increase, owing to a decrease in productivity, and if the nominal wage were constant, the real wage would fall below the value of labour power and the worker’s standard of living would deteriorate. In this situation, workers might demand a higher wage, to compensate for the effect of the increase in the value of necessities, because the value of necessities determines the value of labour power.

- If the value of necessities were to decrease, owing to an increase in productivity, the value of labour power would decrease, as would the price of labour power – the nominal wage. Hence, the real wage – the command value of labour power – would stay the same, as would the worker’s absolute standard of living. However, the worker’s relative standard of living – the material position of the worker in relation to the material position of the capitalist – would deteriorate because, owing to the increase in productivity, the amount of surplus labour, and hence the rate of profit, would increase (other things being equal). In this situation, workers might try to obtain a share of the increase in productivity, and thereby retain their relative social position, by demanding a higher nominal wage.

In the second scenario, Marx considers the impact of a change in the value of money on the price of necessities and the worker’s standard of living. What would happen, Marx asks, if the value of necessities, and hence the value of labour power, were to stay the same, but the prices of necessities were to rise, following a decrease in the value of money? In this situation, the worker’s standard of living would deteriorate. In consequence, the worker might defend their standard of living by demanding a higher nominal wage, in compensation for the effect of the depreciation of the currency.

In the third scenario, Marx considers the impact of a change in the length of the working day on the ability to exercise labour power. Marx tells us that capitalists are trying, continually, to extend the length of the working day so that they can extract a greater quantity of surplus labour from production and stay ahead of their competitors.

In response to an increase in the length of the working day being forced on them by the capitalists, workers may demand that a legal limit be imposed on this length, or demand a higher wage from the capitalist, in compensation for the “greater amount of labour extracted, and the quicker decay of the labouring power thus caused.”

Moreover, if a legal limit were imposed on the length of the working day, capitalists might respond by imposing, on the workers, an increase in the “intensity of labour” whose effect exceeds the effect of the decrease in the length of the working day.[4] Once again, the increase in the intensity of labour causes a greater loss in the value of labour power, and workers may demand an increase in wages, in compensation for this loss.

In the fourth scenario, Marx considers the impact on wages of the economic cycle. If the market prices of all commodities fluctuate around their natural prices, workers must try to resist the downward pressure on wages that is the result of an economic slump and try to obtain, during an economic boom, as large an increase in wages as they can so that, on average, the price of their labour power corresponds to its value.

Questions for discussion

- What is the effect of an increase in the value of necessities on the living standard of workers?

- What is the effect of a decrease in the value of necessities on the living standard of the workers?

- Why might workers demand higher wages, in response to an increase in the length of the working day?

- How might capitalists respond to a legal limit on the length of the working day?

- Why should workers try to obtain higher wages during an economic boom?

XIV. The Struggle between Capital and Labour and Its Results

Marx’s starting point in the first section of the final chapter is the question of “how far” the class of labourers “is likely to prove successful” in its struggle with the class of capitalists.

Marx reminds us that the average market price of labour power will be equal to the natural price of labour power – its exchange value – because the fluctuations in the market price will offset each other, just like for all other commodities.

However, Marx asks us to think about “some peculiar features which distinguish the value of the labouring power … from the values of all other commodities.” There are two types of limit, Marx argues, that make the value of labour power distinct: a physical limit and a social limit.

- The physical limit to the value of labour power is such that, for labour power to be maintained and reproduced, workers must consume a certain quantity of goods and services; the nominal wage must therefore be sufficient for them to purchase this quantity of necessities.

- The social limit to the value of labour power is such that its value must be sufficient to satisfy the “traditional standard of life” of the working class, or the wants that arise from the particular conditions in which different groups of workers are reared and live. This is why, when we compare the value of labour power of “different countries” or the value of labour power of “different historical epochs of the same country”, we find that the value of labour power varies, despite the values of other commodities being constant.

However, historical experience shows us that it is possible for capitalists to exceed, not only the social but also the physical limit to the value of labour power, in other words, to pay wages so long their recipients need some kind of state welfare or charity to get by.

Having discussed the limits to the value of labour power, or the “minimum” level of the wage, Marx discusses the limits to the profitability of production, given the inverse relationship that exists between wages and profits. Marx tells us that

- for a given length of the working day, the limit to the rate of profit is the “physical minimum of wages”;

- for a given wage, the limit to the rate of profit is the “physical maximum of the working day” – that is, the maximum amount of time, in the day, that labour power can be in exercise, before the labourer becomes exhausted.

The actual rate of profit, and the actual level of the wage and the length of the working day, will therefore be determined by the outcome of the struggle that ensues between the class of capitalists and the class of labourers.

As productivity improves, the share of fixed capital (the instruments of production) increases in relation to the share of variable capital or wages – what Marx calls the “progressive change in the composition of capital.” The increase in the demand for labour power will diminish in relation to the increase in the demand for instruments of production.

In short, the general consequence of the development of capitalism is a tendency for the price of labour power to fall “more or less to its minimum limit.” How, then, should workers respond? In the short term, Marx argues, the working class must certainly not give up any attempt to resist the pressures of the capitalists; if workers were to give up, “they would be degraded to one level mass of broken wretches past salvation.” Given the social context into which they are thrown, workers have to sell their labour power to survive and cannot avoid coming into conflict with the capitalists.

In the short term, therefore, workers should certainly organise themselves into trade unions to develop their strength, as a class, in the struggle against the capitalists; but, in the long term, they must go further than resistance and use their collective strength “as a lever for the final emancipation of the working class”.

Questions for discussion

- What distinguishes the value of labour power from the value of other commodities?

- Why is the minimum level of the wage, for a given length of the working day, a limit to the rate of profit?

- Why is the maximum length of the working day, for a given wage, a limit to the rate of profit?

- How do capitalists tend to react to a shortage of labour power and what are the consequences of such a reaction?

- How should workers respond, in both the short term and the long term, to the tendency for the price of labour power to fall to its minimum?

Notes

[1] The manuscript was also published in Germany in Die Neue Zeit in 1898 under the title Wages, Price and Profit.

[2] Of course, if production is to be profitable, there must also be a sufficient level of demand, for the goods and services that the capitalists offer for sale, because it is only through the exchange of goods and services for money that the surplus value that is embodied in them is realised as profit.

[3] The financial capitalist remains the owner of the instruments of production, until the industrial capitalist has repaid the principal and interest of the loan.

[4] In the UK in the 19th century, for example, capitalists demanded a faster pace of work, when new machinery was introduced in the factories, in response to the limits on the length of the working day that the Factory Acts provided for.