In the second part of his analysis of the US elections, John Peterson of Socialist Appeal USA examines the role of identity politics in the Democratic candidates’ campaigns, and outlines the perspectives for the movement of the American working class.

In the second part of his analysis of the US elections, John Peterson of Socialist Appeal USA examines the role of identity politics in the Democratic candidates’ campaigns, and outlines the perspectives for the movement of the American working class.

Women voters

For decades, the Democrats enjoyed the almost guaranteed support of an overwhelming majority of trade union, black, Latino, and LGBTQ+ voters, as well a healthy overall majority among women and the youth. This was to be the foundation of Hillary’s nomination and eventual installment in the White House. However, these layers of the population—the most downtrodden and affected by the grinding economic crisis—have not rallied around her as expected. Instead, many have responded enthusiastically to Sanders. Although she pulled off a win on Super Tuesday, her march to the coronation has been nowhere near as smooth as she anticipated.

Gail Sheehy outlined what is happening in an opinion piece for the New York Times: “Kathryn Levy, a poet and arts educator of Mrs. Clinton’s vintage, said: ‘Between Hillary coming so close to winning the nomination in ’08, and an African-American man winning the election, that narrow mold of who could be president has already been broken . . . A female editor at a prestigious national magazine confided: I should be jumping up and down with enthusiasm for Hillary’s candidacy, but I’m not.’ I asked if she would vote for Hillary in the end. ‘I am waiting to see if Bernie wins Iowa, she whispered. If so, I’m right there!’

“In the 2008 presidential election, many boomer women, especially self-described ‘born feminists’ like Lorraine Dusky, a writer and activist based on Long Island, started out as monotheistic Hillary worshipers. When a young, passionate African-American senator stole her thunder, ‘most of the Democratic women I knew turned to Obama.’ . . . This time, Ms. Dusky, having passed 70, said: ‘I’m feeling Clinton fatigue. Even exhaustion.’

“The Rev. Katrina Foster, a Lutheran pastor for 21 years, told me, ‘I’m no longer interested in the physical packaging of these candidates.’ Pastor Foster, who is gay, acknowledged that Mrs. Clinton finally had the right position on gay issues. ‘But we now have won rights, I’m more concerned with what we have lost — what it means to be an American.’ She is leaning toward supporting Bernie Sanders.”

Huge numbers of young women have enthusiastically backed Sanders’ campaign. Gloria Steinem’s smug assertion that these women have flocked to Sanders because “that’s where the boys are,” is just one example of the growing disconnect between the old guard and the youth. Then there was Madeleine Albright’s infamous comment that “there is a special place in hell for women who don’t help each other,” which provides a valuable lesson in dialectics. For 25 years, that line apparently played well to audiences. Now things have turned into their opposite. Not only didn’t it connect, but it badly backfired. Then there is Clinton herself, who has scolded young women like a disappointed parent for not backing her, including this young black woman.

A recent article in the New York Times provides the following insights on the growing disconnect, based on discussions with students at Penn State University:

She and her friends note that the nation already has a black president; they see themselves in a postgender world. As Ms. Sandidge, also African-American, said, “I don’t find gender that important.” . . .

It is as if Mrs. Clinton’s campaign, based partly on revealing the power of female voters, has instead revealed something else: a generational schism that threatens to undermine it. Mrs. Clinton lost the women’s vote in New Hampshire by 11 percentage points. Broken down by age, the results were even more striking: She led by 19 points among women 65 and older, but trailed by a huge margin, 59 points, among millennial voters, ages 18 to 29 . . .

Many younger women already take for granted some of the gains that those before them fought for, and they identify strongly with their generation’s collectiveconcerns — student debt, finding a job in postrecession America, and the fight for gay rights and a more flexible view of gender than their parents considered . . .

Polls suggest Americans in both parties long ago became open to a female occupant of the Oval Office. By 1999, as Elizabeth Dole contemplated running for the 2000 Republican nomination (she did, unsuccessfully), the Gallup organization found that 92 percent of Americans said they would vote for a woman. Ms. Lake said that number was inflated, because voters are not often truthful with pollsters. Still, when Gallup first asked that question, in 1937, the figure was 33 percent.

Yet as Kellyanne Conway, a Republican strategist who runs the “super PAC” that backs Senator Ted Cruz of Texas, says, it is impossible to divorce a theoretical question about women from the realities of a specific candidate. If young women are not excited by Mrs. Clinton, Ms. Conway says, it is because they reject her message, or do not relate to her.

“People no longer hear, ‘Do you want a woman to be president?’” she said. “They hear, ‘Do you want that woman?’”

Black voters

And what about the so-called “black vote,” which was likewise supposed to be all but guaranteed to Hillary? Earlier on in the campaign season, Sanders was confronted by Black Lives Matter activists who called him out publicly for not making police brutality a central part of his campaign. To many, this awkward clash seemed like a confirmation that an “old white dude” couldn’t possibly connect with black voters. His response was to raise the issue of police brutality in his stump speeches and to bring several BLM activists on to his staff, some of whom have gone on to play a leading role in generating support for him in states like South Carolina.

And what about the so-called “black vote,” which was likewise supposed to be all but guaranteed to Hillary? Earlier on in the campaign season, Sanders was confronted by Black Lives Matter activists who called him out publicly for not making police brutality a central part of his campaign. To many, this awkward clash seemed like a confirmation that an “old white dude” couldn’t possibly connect with black voters. His response was to raise the issue of police brutality in his stump speeches and to bring several BLM activists on to his staff, some of whom have gone on to play a leading role in generating support for him in states like South Carolina.

Hillary lost this bellwether state in 2008 to Obama, and this time around, it was felt by many that black South Carolinians “owed” the Clintons. This view was summed up by former Senate Democratic staffer Jimmy Williams, a native of the Palmetto State, in a pre-primary article on MSNBC: “Hillary’s lead in South Carolina is simply insurmountable, due specifically to the black vote, and this notion that he’s peeling away black voters from her is a myth. What black voters in South Carolina want is simple. They want someone who loves God, won’t lie to them, will protect America and will fight against racism. And the Clintons are literally family to black South Carolinians.”

However, this paternalistic attitude, which sees black voters merely as political capital, an amalgamation of quid pro quo favors to be called in, come election season, backfired among the youth. Although Hillary succeeded in maintaining the support of a majority of black voters, there is a clear generational split, as the youth drift toward Sanders. Sanders comes across as sincere and honest, and this connects with those who have come to scorn the artificially choreographed poll-and-focus-group-driven Clinton machine. Most importantly it gives lie to the myth that black voters somehow care only about “black issues.”

Issues such as police brutality resonate deeply with black Americans. But the reality is that this many-times oppressed layer of the working class has little to lose and much to gain if capitalism is overthrown and replaced by genuine socialism. Historically, there are deep reserves of radicalism, pro-socialist, anti-imperialist, and pro-union sentiment among the black population. Black workers are more likely to be in a union than any other demographic. The vast majority of black Americans are workers, often among the worst paid, and it is working class issues that resonate the most.

Once again, the truth is concrete. Sanders’ call for socialism, a higher minimum wage, universal education and health care connects far more with the average black worker, especially the youth, than something Bill Clinton may have done “for black people” 20 years ago. Nonetheless, Sanders faced an uphill struggle to make up for decades of political preparation for these elections. The Clintons are a household name and have effectively been on a constant presidential campaign since the 1970s—promising “eight years of Bill, eight years of Hill.” But once again, the generational divisions are coming into focus.

As for LGBTQ+ voters, Sanders has supported marriage equality for decades, whereas Clinton only recently opportunistically changed her position to align with majority opinion. It is difficult to find solid statistics, but the quotes in the New York Times cited above would seem to indicate that this too is no longer a guaranteed demographic for the Democratic Party establishment candidate. And Latino voters, while still overwhelmingly for Clinton, are less enthusiastically Democratic than in the past, as was evident in Nevada. There is surely a generational gap deepening here as well.

The labor movement

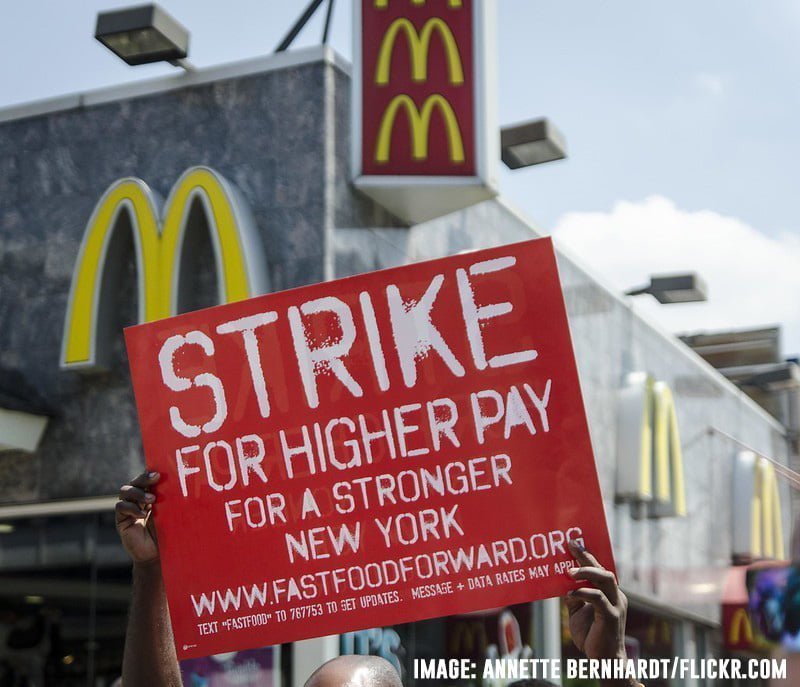

This brings us to the all-important and decisive question: the organized working class. Although numerically weakened by decades of attacks and sell-outs by the class-collaborationist leadership, union workers represent a powerful force in society. In 2015, the overall unionization rate was only 11.1%. However, this amounts to 14.8 million union members, with another 1.6 million workers who report no union affiliation but whose jobs are covered by a union contract. 35.2% of the public sector is unionized, above all teachers, federal, state, and municipal workers. And while only 6.7% of workers in the private sector are unionized, this is in key sectors of the economy: utilities (21.4%), transportation and warehousing (18.9%), educational services (13.7%), telecommunications (13.3%), and construction (13.2%).

Tensions have risen within many unions over the question of endorsing Clinton versus Sanders. Many large unions rushed to endorse Clinton early in the campaign season to cut across this. Despite the pressure from above to stick to the “tried-and-true,” several unions went ahead and endorsed Sanders anyway, including the influential National Nurses United, American Postal Workers Union, and the Communication Workers of America. In a clear nod to the pressure against a presumptive endorsement of Clinton, the AFL-CIO has declined to endorse one candidate or another for the time being.

Millions of workers are excited by Sanders despite his running as a Democrat. Millions of others are still on the sidelines precisely because of his association with the party in power. Although Sanders’ program is left-reformist at best, all of the above shows that there is indeed a natural basis for a labor party based on the unions and rising support for socialist ideas.

Sanders’ broad fundraising base highlights this potential. He has received donations from over four million individuals and out-fundraised Clinton in February ($43 million to her $30 million). His refusal of money from Wall Street is a major source of his support. The unions have even more resources, above all the real-world social networks and infrastructure that could organize a massive rank-and-file campaign to get out the vote if it mobilized its full potential around an independent campaign. In many states, were it not for the unions, Clinton would have little in the way of a ground game. If the plug were pulled and instead channeled into an independent bid by Sanders, it would mean the effective end of the Democratic Party in its current form.

How will a labor party be formed?

Is it possible that a split in the Democrats could lead to the formation of a labor party? Of course it is. For years we have explained that a split off from the Democrats, which would eventually break away the major unions, was one possibility. In Brazil, the Workers’ Party (PT) was formed on the basis of many smaller unions and the broader working class, before eventually winning over the larger unions in the CUT federation. We even named potential Democrats such as Dennis Kucinich, who at one point might have split away over support for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. We pointed to potential support from unions such as the National Nurses United, whose leaders supported the short-lived effort to form the Labor Party in the 1990s.

The US Marxists have never had a rigid approach, or mechanically asserted that the process would be exactly as it was in Britain, where the unions took the initiative to set up the political party, though even there it was not a linear process. That was our basic working hypothesis, based on the conditions in the US. But we always left open the possibility of other variants. Given the state of the trade union leadership, we believed that this was not necessarily the most likely scenario, and that something far more amorphous was likely in the initial stages. But the objective necessity would remain a class-independent party with the backing of the main unions, even if they didn’t all break from the Democrats at once.

Clearly, there is no preconceived schema that can be imposed, as it would be impossible to work out in advance the exact path to a labor party. What we can say is that whatever form it takes, its coalescence will be a process, with many streams of struggle, both political and economic, both in and out of the existing union structures, coming together over time. Depending on how events unfold, it is even possible that the future labor party will be called “The Democratic Party.” If that is the case, we will be there with our class. What concerns us above all is the content of such a party, not the outward form or the name. Whatever zigs and zags history takes, we will retain our connection to the working class and its organizations, fighting for our program and the socialist revolution.

Unfortunately, the current crop of pro-capitalist labor leaders has no interest in rocking the boat. In fact, they have become the greatest objective obstacle on the path of independent working class organization, both political and economic. But the class struggle in the coming period will violently shake up the labor leadership. They will no longer be able to coast along on empty promises of better things to come if only the lesser evil is supported. This worked in 2008 and 2012, but with literally nothing given in exchange by Obama, it is becoming a harder and harder sell.

No matter who ends up as the Democratic nominee, the “lesser evil” pressure to “defeat the right” will be merciless in the general election. To help ground us in resisting this onslaught, we should be clear that lesser evilism represents the pressure of alien classes: both those who don’t want the workers to take economic and political power, and those who have no confidence that this is possible.

Although polls are mixed as to whether or not Trump can be beaten by a Democrat, it remains to be seen whether the lesser evil mantra will have the same effect as in the past. When you cry wolf once too often, people stop listening. The bitter lesson that US workers will likely be forced to endure at a certain stage, is that by not building a viable alternative to the “lesser evil,” the “greater evil” will eventually make its way back into power. Needless to say, a Trump presidency would quickly disabuse those with illusions in his populist demagogy, further eroding support in the two-party system, and creating even more potential labor party supporters. The wave of protests and mobilizations his election would unleash would introduce even more instability to the equation.

Which way forward?

The contradictions and disparities of capitalism are in many ways more acute and intractable in the US than anywhere else on the planet. The protective layer of fat accumulated during the postwar years is rapidly burning away. Virtually all the key institutions of capitalist rule are discredited. The old guard of both parties is rapidly blowing its political capital, which will mean even less room for maneuver in the future. The capitalist class is no longer sure how to maintain its rule. This is the explanation for the incredible array of candidates who have presented themselves in this year’s election.

The contradictions and disparities of capitalism are in many ways more acute and intractable in the US than anywhere else on the planet. The protective layer of fat accumulated during the postwar years is rapidly burning away. Virtually all the key institutions of capitalist rule are discredited. The old guard of both parties is rapidly blowing its political capital, which will mean even less room for maneuver in the future. The capitalist class is no longer sure how to maintain its rule. This is the explanation for the incredible array of candidates who have presented themselves in this year’s election.

Enormous social energy is building up in this country, and once provided an outlet, it will set the entire planet on a different course. If Sanders loses the nomination, chooses not to endorse Clinton, and instead sets out on his own, it could have far-reaching consequences. Even if he fails to win the presidency as an independent in 2016, it could lay the foundations for a mass working-class alternative at all levels of US politics. It would shock the union leadership out of complacency and energize the rank and file, widening the chasm that exists between their interests. However, none of this is guaranteed this electoral cycle, and we will have to attentively see how things play out.

One thing is certain: the question of how socialism is perceived in the US will never be the same. The Marxists can build our forces as a result. It is crucial, therefore, that we have a sense of proportion and position ourselves for the future. There is a big difference between perspectives and wishful thinking, just as there is a difference between the first and the ninth month of pregnancy. There are no shortcuts to building the revolutionary party. We are in the early days of this process and cannot get carried away. The next few months will be extremely interesting and important, but the coming years will be even more momentous, and we we must prepare for this.

We cannot take any responsibility whatsoever for the Democrats in their present form. Sanders is a historical accident, in the sense that nature abhors a vacuum, and he has filled it. What is most important is not Sanders or his campaign as such, but the social forces he has awakened to political life and activity. Those most interested in joining a revolutionary Marxist organization such as the IMT can already see through the Democrats. As we have explained, they are excited about Sanders despite the Democrats, not because of them. They can see that support for his campaign represents a tidal change of public opinion and can sense the opportunity this represents to spread the ideas of socialism.

Even if Sanders succeeds in winning the presidency as a Democrat, none of the fundamental problems facing US workers can be resolved within the limits of capitalism. Likewise, if he breaks with them and runs as an independent, the fundamental need to break with capitalism would remain. There is no way forward on the basis of this system. We must explain that even the most modest of reforms will be difficult if not impossible to implement in the midst of the capitalist crisis, and that even if some positive reforms can be wrenched from the bosses, capitalist exploitation and oppression will continue. In order to fundamentally change society, far more will be required than a vote at the ballot box, the passing of a few laws, or modestly higher taxes on the rich. We must patiently explain that what is really needed is the nationalization of the big banks and the Fortune 500 under the democratic control of the workers, to be run in the interests of the majority, not the 1%.

Sanders often says that his campaign “is not just electing a president, it’s about transforming America.” He has also stated repeatedly that one person cannot bring about the kind of change that is needed. Millions of people can relate to these statements and want to do something about it. So far, Sanders has restricted himself to working within the existing political and economic system. He has called in the abstract for a mass movement to support his candidacy, but has not initiated the process whereby the necessary organizational structures can actually be formed, structures which simply do not and cannot exist within the parameters of the Democratic Party machine.

Super Tuesday graphically exposed the limitations of attempting to bring about change through the Democratic Party, and the potential that exists to build something viable outside that electoral machine. This is why we say: if you want to fight for Bernie’s progressive ideas and against the billionaires, you must break with the Democrats, break with capitalism, build a labor party, and fight for socialist revolution! Although for many this sounds “too radical,” those who are looking for serious answers to a serious crisis are very open to these ideas. And as we have seen, opinions can change quite rapidly. Millions of those who reject this perspective today will embrace it in the future.

Through a series of successive approximations, the US working class will test one party and leader after another. In time, American workers will come to the conclusion that nothing less than a socialist revolution is required. As Leon Trotsky explained in If America Should Go Communist, “Yet communism can come in America only through revolution, just as independence and democracy came in America. The American temperament is energetic and violent, and it will insist on breaking a good many dishes and upsetting a good many apple carts before communism is firmly established. Americans are enthusiasts and sportsmen before they are specialists and statesmen, and it would be contrary to the American tradition to make a major change without choosing sides and cracking heads.”

Under American conditions, this process will unfold in many dramatic stages. There will be exciting victories and demoralizing defeats, but the workers will learn from the experience. What is most encouraging for the future is the attitude of the youth. This is the real guarantee for fundamental transformation in this country and around the world in the historical period we have entered.

The crisis of capitalism will not end until capitalism is ended. And until the necessary revolutionary leadership is forged, ending capitalism will be impossible. When the revolution reaches a crescendo, if the Marxists are not present in sufficient numbers, the revolutionary floodtide will eventually ebb. This must imbue us with a sense of urgency.

Engels on the US working class

Karl Marx’s lifelong collaborator, Frederick Engels, made the following scathing indictment of US politics in 1892, which provides useful insights into the support for Donald Trump 124 years later:

“The small farmer and the petty bourgeois will hardly ever succeed in forming a strong party; they consist of elements that change too rapidly—the farmer is often a migratory farmer, farming two, three, and four farms in succession in different states and territories, immigration and bankruptcy promote the change in personnel, and economic dependence upon the creditor also hampers independence—but to make up for it they are a splendid element for politicians, who speculate on their discontent in order to sell them out to one of the big parties afterward.

“The tenacity of the Yankees, who are even rehashing the Greenback humbug, is a result of their theoretical backwardness and their Anglo-Saxon contempt for all theory. They are punished for this by a superstitious belief in every philosophical and economic absurdity, by religious sectarianism, and by idiotic economic experiments, out of which, however, certain bourgeois cliques profit.”

But the same Engels made the following remarks in 1886 on the process of the formation of a labor party:

“The first great step of importance for every country newly entering into the movement is always the organization of the workers as an independent political party, no matter how, so long as it is a distinct workers’ party. And this step has been taken, far more rapidly than we had a right to hope, and that is the main thing. That the first program of this party is still confused and highly deficient, that it has set up the banner of Henry George, these are inevitable evils but also only transitory ones. The masses must have time and opportunity to develop and they can only have the opportunity when they have their own movement—no matter in what form so long as it is only their own movement—in which they are driven further by their own mistakes and learn wisdom by hurting themselves.

“The movement in America is in the same position as it was with us before [the revolutions of] 1848; the really intelligent people there will first of all have the same part to play as that played by the Communist League among the workers’ associations before 1848. Except that in America now things will go infinitely more quickly . . . If we in Europe do not hurry up the Americans will soon be ahead of us. But it is just now that it is doubly necessary to have a few people there from our side with a firm seat in their saddles where theory and long-proved tactics are concerned.”

With a delay of well over a century, the US working class is once again shaking off the cobwebs of a long hibernation and seeking alternatives to the existing state of affairs. In a world of endless distractions, sensory, and information inputs, the need for theoretical clarity, perspectives, and patience is greater than ever. Turbulent waters are necessarily muddy and confused, and things will only get more complicated before they are clarified. But we study dialectical materialism for a reason: in order to apply it to complex processes such as this.

It is said that the darkest hour is before the dawn. The Marxists have passed through a tough period in which socialist ideas were marginalized in US society and a general malaise and apolitical apathy prevailed. We had relatively few opportunities to connect with wider layers of the workers and youth. But that is beginning to change. While there are plenty of storm clouds ahead, the first rays of light are beginning to shine above the horizon. As the curve of historical development accelerates, we can look ahead with great optimism to a revolutionary socialist future.

Published on In Defence of Marxism