Tensions are rising in higher education, as university bosses – under pressure from competition and marketisation – look to use recorded lectures to undermine the job security and conditions of staff. Workers and students must fight back.

The higher education (HE) sector faces another turbulent and disrupting academic year, as university bosses make a grab for performance rights over recorded teaching sessions.

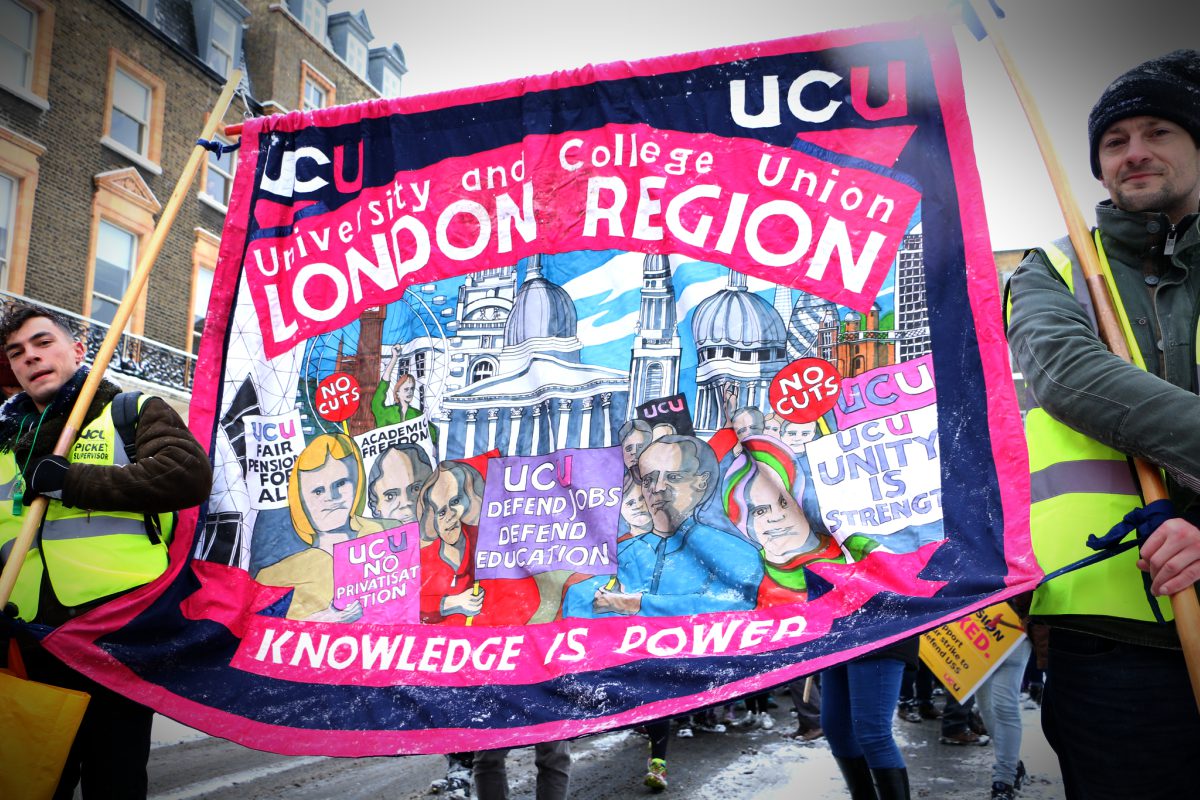

A press release from the University and College Union (UCU) last week, on 3 September, warns education providers that there will be strike action, if they pursue plans to re-use and store lectures and seminar sessions that have been recorded during the pandemic.

For the purpose of property law, these are classified as ‘performances’. The rights to the performance and its recording, in turn, belong not to the institution but the worker.

This means the education provider needs to licence the recording from the staff member; and that the worker in question can withdraw the consent to use, store, or reuse a recorded teaching session at any time.

Scab recordings

With the new academic year approaching, the potential misuse by the employers of these recordings has become yet another sticky issue between UCU members and university bosses, heightening tensions even further.

Three out of five universities plan to keep some form of widely unpopular blended teaching. A rising number of local disputes are ongoing over job cuts and blacklisting. And a national dispute is on the horizon over pension cuts.

While the pre-recorded sessions made education more accessible during the pandemic, allowing students to access and catch up on any missed content, they also pose a risk to job security, if education providers store and re-use them.

This would also jeopardise any industrial action by lecturers, allowing university management to deploy these recordings during future strikes. In effect, academic workers are faced with the possibility of being scabbed on by themselves!

Casualised contracts

A particularly disgraceful example of where this will lead can be found at the University of Exeter.

There, HE bosses are trying to push through a licence agreement that would give the institution control over any recordings for five years, with no regard to the contract length of the staff member.

Furthermore, this latest move adds insult to injury. In their 2020 report on casualised work, the UCU finds that a third of all workers in colleges and universities are employed on short, fixed-term contracts.

Many of these contracts last as little as nine months – not even covering a full academic year. This means that staff are de facto laid off as soon as students leave the campus for the summer break.

If the employers in Exeter are successful, they could sack staff and keep charging students to watch the sessions.

Breaking point

The online material that kept education running in the past two academic years has been produced under the most depressing conditions. Understaffed and overworked, many lecturers invested in training and equipment themselves, since HE institutions failed to provide time and resources for either.

The pressure to stick to the academic schedule was driven by competition, with no concern for students or staff. Workers in further and higher education have been pushed beyond breaking point, with waves of job cuts ripping through the sector, affecting every layer of staff.

The arguments of the employers about accessibility and safety are hollow and insincere. They have no intention of hiring the numbers of staff that are required to deliver safely distanced, in-person teaching. Nor do they have qualms about forcing students onto campus and into crowded accommodation, just to watch pre-recorded lectures.

Instead, the employers are filling their reserves with students’ tuition fees and workers’ pensions – which in turn are being invested in bubbles such as that of private student accommodation.

Unite and fight

Students and staff solidarity is needed now more than ever.

Education should be free and accessible to all. Free online material could be a great resource for society. But under marketisation and capitalist competition, online lectures result in staff being made redundant, and in students being charged more – all for a style of education they don’t even want.

There is no way to resolve this contradiction within the current system. Only a planned, democratically run economy – with education run under staff and student control – can provide both secure jobs and free education for all.