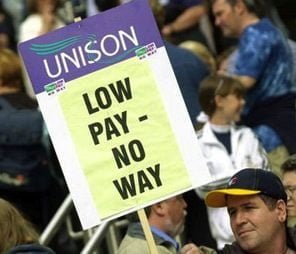

The results of Unison’s ballot in local government and schools were announced recently. The overall headline figure was that 75% of members voted in favour of strike action, but on a turnout of just 31%.

While this figure is far higher than the percentage turnout in last year‘s ballot (13%), it still falls far short of the 50% legal threshold required to strike in a national ballot.

This was a disaggregated ballot, however, with turnout calculated from employer to employer. On this basis, majorities for action were achieved in around one in six of the 4,342 employers balloted.

These results reveal some of the contradictions within Unison. More than anything else, they will leave hard-pressed members scratching their heads, wondering what they have to do to get their huge union – with around 350,000 members in local government and schools in England and Wales – to take action.

Make no bones about it, many rank-and-file Unison members are struggling. Low pay; increased pressure at work; rapidly rising prices; decades of cuts and austerity: all these have had a dramatic impact on services, and on the character of the work we do.

This pent up discontent is reflected in the percentage who voted to strike: three out of every four members who cast their ballot. But given the Tory anti-union laws, in most employers, the turnout was not high enough to translate this into actual action.

Britain has seen an incredible strike wave over the past year. Why, then, when workers in other unions across the movement are on the move, has it proved so difficult to get a mandate for action in Unison?

Narrow base

Unison is a huge union, with more than a million members. But up until recently, it has suffered from years of right-wing domination at a national level. Leaders have always taken the path of least resistance, and have propagated a culture of ‘servicing’ members on an individual basis, rather than organising collectively to fight for change.

The union’s activist base is very narrow. Recently it came to light that Unison has something like 12,000 active lay members. This represents less than 1% of the total membership.

These activists are spread very thinly, amongst more than 830 branches nationally. And many of these branches barely ever meet, providing few opportunities for rank-and-file members to actively engage with the union.

The majority of employers in the recent ballot, meanwhile, are in schools. Metropolitan authorities in the big cities may have up to 100 primary and secondary schools. Some of the counties have many more.

Most local government branches will have a handful of shop stewards in schools. Even the most active and well-organised branches will struggle to keep in regular face-to-face contact with members. This makes it difficult to get the vote out come the time of strike ballots.

Academisation of schools has become an additional complicating factor, with multi-academy trusts taking over former local authority schools. It can be especially difficult for trade unionists to gain access to academies in order to organise and conduct union activity.

Yet despite this, many of the successful ballots were in schools. This illustrates the impact that one or two determined people can have in convincing their friends and colleagues to take action.

Bureaucratic brake

The union employs an army of full-time officers, amounting to some 1,200 people. But far from promoting activity and developing a fighting leadership at a branch level, the bureaucracy – especially at its highest levels – represents a colossal brake on the union, resting on a passive and compliant lay leadership in many branches.

The Unison bureaucracy has always been reluctant to take on the employers – and especially the Tory government. Their argument has essentially been (and continues to be) that members should keep their powder dry, and wait for a Labour government.

After all, as one former head of local government was heard to say: “If the miners couldn’t defeat the Tories, what hope do we have?” This pessimistic, cynical attitude permeates the bureaucracy and the right wing of the union.

For decades, this bureaucracy has paid lip service to the ‘fight against low pay’, and to the myriad of other campaigns that members have agreed to support at national delegate conferences and in the service group conferences.

Grassroots anger against this passive, conservative approach at the top has given rise to a struggle at a national level between the left and right, and between the left NEC and the bureaucracy, to transform the union.

It is impossible for the left to win this struggle within the confines of committee meetings, however, as has been attempted so far. Instead, the left must mobilise the membership.

Over the years, meanwhile, left activists have been marginalised, with many expelled or suspended. Essentially the union’s active base has been hollowed out.

This has been accentuated by the funding crisis in local government, with job losses cutting off the flow of young people into council jobs – and into the union.

Run aground

The latest local government pay campaign reflects the transition taking place inside the union.

The key negotiating committee – the National Joint Council (NJC) Committee – is elected by branches in the regions, and isn’t directly elected by the local government service group executive, which has a left majority.

The NJC committee has a majority of right wingers. But the left won the argument this year over the question of going straight to a national strike ballot, following last year’s long drawn-out pay campaign, which fizzled out over winter.

This year’s NJC vote reflected the pressure from below – from a membership struggling with the cost-of-living crisis and huge hikes in bills.

The problem, however, is that you can’t turn the membership on and off like a tap. To build for a successful strike ballot nationally – in a massive union such as Unison, with members in thousands of schools and workplaces – requires the full commitment and support of the officials and local leaderships, and a tremendous amount of work by activists on the ground.

It is evident that the best results were achieved in well-organised branches with a left leadership. Lambeth Unison, for example, recorded an 89.6% Yes vote on a 57.2% turnout – easily a mandate for action. Unfortunately, at the moment, this has proved to be an exception, not the rule.

Calls have been made for branches that returned over 40% turnouts to be re-balloted. But it seems that the NJC committee voted against taking further action, with only a handful of delegates voting for. Essentially, then, this year’s pay campaign has been run into the sand.

Status quo

It is clear that Unison cannot continue on the same tired and discredited path. Something has to change.

This means becoming an active fighting union, taking up the battle on the ground, and demonstrating Unison’s capacity to achieve real results for members.

For far too long, the bureaucracy has sat on local disputes and campaigns. For far too long, left activists have been witch-hunted and marginalised.

In the current economic climate, members are desperate for decent pay rises and better working conditions. Too few people are doing too much work in schools and councils; in hospitals and services. Yet Unison seems largely ineffective when it comes to breaking this status quo.

This is clearly apparent in the NHS, where both junior doctors in the BMA and the previously inert RCN nursing union, thanks to the determination of rank-and-file members, have clearly outflanked Unison.

But in reality, in local government and schools, where Unison is dominant, the situation is just as bad.

Fighting union

Unison must become a fighting union, showing its relevance to every member, by demonstrating in practice what can be achieved on the basis of militant action and bold socialist policies.

To achieve this, the left in Unison – organised around the Time for Real Change banner – must take the class struggle into every classroom, every office, and every depot, and must mobilise grassroots members to complete the transformation inside the union.

Unison needs not 12,000 activists, but 50,000 or 100,000 organised and educated rank-and-file members. We need a shop steward in every workplace.

As a means to this end, Unison needs an open and democratic broad left organisation, capable of reaching every branch, region, and service group, in order to link the day-to-day struggles with the need to transform the union, and to arm it with a clear socialist programme.

Unison Socialist Appeal supporters will participate energetically in this struggle, linking today’s battles – against inflation and austerity, and for a fighting union – to the need for a fundamental transformation of society along socialist lines.