Given the deepening crisis of world capitalism, the catastrophic position of British capitalism in particular, and the reawakening of the British working class, the republication of Leon Trotsky’s Writings on Britain by Wellred Books could not have come at a more opportune moment.

These writings cover an array of subjects, which reveal the encyclopaedic scope of Trotsky’s knowledge and his grasp of the material.

In his short work Where is Britain Going? (1925), which can be found in this collection, Trotsky predicted revolutionary upheavals that were inherent in the situation. His prognosis was confirmed in the 1926 general strike.

The book was translated and promoted by the British Communist Party, which at that time was a young revolutionary party, unaffected by Stalinism. Trotsky explained:

“… whatever the partial fluctuations in the economic and political conjuncture, everything points to a further aggravation and deepening of those difficulties which Britain is currently undergoing and thereby to a further acceleration of the tempo of revolutionary development.”

Trotsky showed how this would affect the Labour Party, which was in the grip of the reformists and opportunists. The coming to power of a Labour government under crisis conditions would, he believed, lead to divisions and splits:

“But in these conditions it seems highly likely that the Labour Party will come to power at one of the subsequent stages, and then a conflict between the working class and the Fabian top layer now standing at its head will be wholly unavoidable.”

In fact, such a crisis Labour government came to power in 1929. Under the impact of the world slump, it ended in the betrayal of Ramsay MacDonald and a split in 1931.

This pushed the Independent Labour Party (ILP), which was affiliated to the Labour Party, to split away in the following year. This propelled the ILP far to the left, towards centrism – a tendency standing between reformism and Marxism.

Sadly, the revolutionary opportunities that arose were squandered by the centrist leaders of the ILP, as well as by the Communist Party, which by now had succumbed to Stalinism.

Rise of the labour movement

Given that it had been the first capitalist country in the world, and the pre-eminent world power of the time, Britain had always been of great interest to Marx and Engels, theoretically and politically.

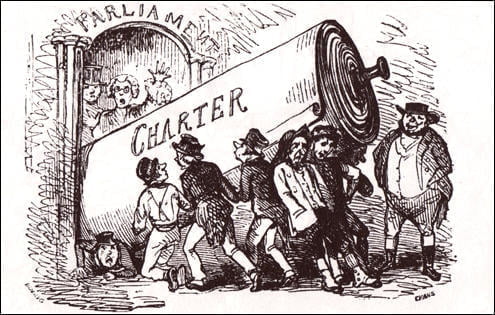

Both Marx and Engels were involved in the struggles of their day, and they collaborated with the leaders of revolutionary Chartism in an attempt to rearm the movement with a scientific programme.

With the demise of Chartism, British capitalism enjoyed a spectacular growth and a monopoly over world trade. Its empire grew to cover a quarter of the globe. On this basis, the British ruling class could share its plunder with a privileged layer of the working class – an aristocracy of labour.

These concessions provided a certain social stability, which permitted an extended period of relative peace between the classes. This period was described by Engels as a “forty year slumber” of the British working class, lasting until the late 1880s.

Britain’s monopoly over world trade was broken by the rise of Germany and the United States, however, leading to a new period of social upheaval and the emergence of New Unionism and the creation of the Labour Party.

Lenin also followed the fortunes of British capitalism and the development of the working-class movement. While the workers had shown class militancy, its leaders were thoroughly imbued with opportunism and reformism, priding themselves on their ‘pragmatic’ outlook and displaying an open contempt for theory.

The First World War and the victorious Russian Revolution transformed the entire world situation, however, shaking British imperialism to its foundations. The loss of its dominant position on the world arena further undermined its position at home.

Empiricism

A simple glance at Trotsky’s writings on Britain is sufficient to see what a host of questions he tackled. He analysed the origins of Britain’s meteoric ascent, in the course of which her ruling class would become the most confident and far-sighted rulers in the world.

“Not for nothing has it been said of the British imperialists that they do their thinking in terms of centuries and continents,” explained Trotsky.

The philosophy of the British bourgeoisie was based upon empiricism, guided by decades of experience. On Britain’s road to becoming a world power, this practical instinct and ‘rule of thumb’ served them well. They had little regard for theoretical generalisations, for the simple reason that their forebears had achieved success without the aid of such abstract understanding.

The rise of the British working-class movement, the first of its kind in history, posed a whole host of challenges before the capitalist class. All attempts to subjugate and crush the early workers’ organisations – with the use of class laws and state repression – had failed. They sprang up like mushrooms after a storm.

The bourgeoisie thus opted instead for a policy of repression and concessions. Part of this flexible approach entailed schemes to buy off and corrupt the leaders of the labour movement – a method that, in most cases, proved very effective.

Nevertheless, such bribery could not prevent the class struggle in Britain from continuing to break through the surface, as it did with the awakening of the working class towards the end of the nineteenth century.

The growing rivalries between the imperialist powers eventually led to an attempt to redivide the world in the form of world war. Revolution was its by-product, epitomised by the Russian Revolution. This opened up a new and dangerous situation for the British ruling class.

Fabianism

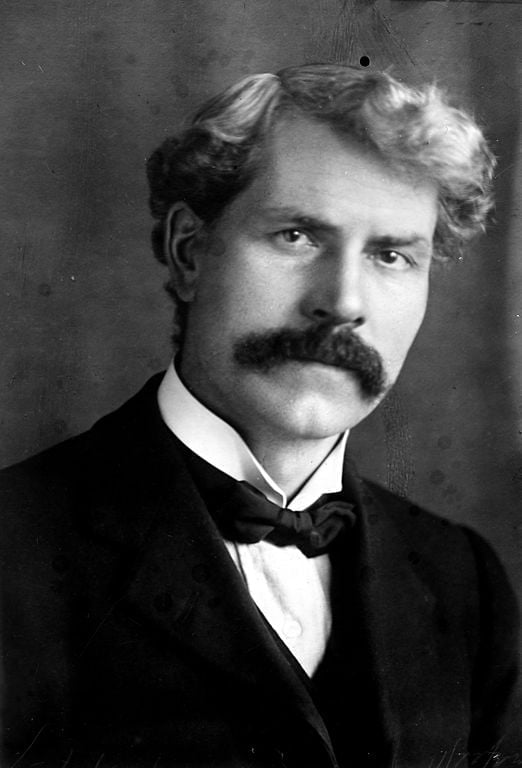

The same period also witnessed the rise of the Labour Party as the mass party of the British working class. The parliamentary leadership of the party, however, represented by Ramsay MacDonald and co., championed Fabianism, gradualism, and a rejection of the class struggle.

“The leaders of the Labour Party represent essentially the bourgeoisie’s political agents,” remarked Trotsky.

He continued to elaborate their role:

“These pompous authorities, pedants, and haughty, high-falutin’ cowards are systematically poisoning the labour movement, clouding the consciousness of the proletariat, and paralysing its will. It is only thanks to them that Toryism, Liberalism, the Church, the monarchy, the aristocracy, and the bourgeoisie continue to survive and even suppose themselves to be firmly in the saddle.”

He concluded by saying:

“The Fabians, the ILPers, and the conservative trade union bureaucrats today represent the most counter-revolutionary force in Great Britain, and possibly in the present stage of development, in the whole world.”

Trotsky’s writings cover one of the stormiest periods of British history: the period of the 1920s, which saw the general strike and its aftermath; as well as the development of Trotskyism in Britain in the 1930s – all of which contain a wealth of analysis that remains startlingly relevant today. This is especially true of Where is Britain Going?

Reversal of fortunes

We are republishing this material in order to bring this method, together with this wealth of knowledge, to the attention of the new generation of workers and youth; to arm and enrich them and prepare them for the tasks of the coming period.

The present is pregnant with revolutionary possibilities and challenges, foremost among which is the challenge of forming a revolutionary leadership. The republication of these writings forms part of the continuation of Trotsky’s struggle to build a revolutionary leadership capable of putting an end to capitalism.

The ruling class of Britain today is utterly degenerate, and has become the complete inverse of what it once was. It was once a great revolutionary class, which, under the leadership of Oliver Cromwell in the English Revolution, did away with the absolute monarchy of Charles I, and that cleared the way for capitalist development.

Thanks to this exclusive historic privilege of development possessed by bourgeois England, conservatism combined with elasticity passed over from her institutions into her moral fibre.

Today, British capitalism has suffered a reversal of fortunes. The once-mighty power of British imperialism has collapsed. The Empire has gone. Britain has been reduced to a second-rate power on the fringes of Europe. In fact, it has become the ‘sick man of Europe’.

All the contradictions, accumulated over decades, have come to the fore, creating one crisis after another. As a result, Britain has been transformed from one of the most stable countries to one of the most profoundly unstable.

No longer far-sighted, the representatives of the bourgeoisie are now decrepit and degenerate, a product of capitalist decline. They have become narrow ‘Little Englanders’, or Brexiteers, eaten up with their baseless self-importance. They are caught in a vice. Everything they do is wrong. An old proverb aptly fits: “Those whom the gods wish to destroy they first make mad.”

The postwar upswing was the heyday of reformism. It was the era of Keynesianism, of ‘managed capitalism’, and of the granting of important reforms, such as the health service.

This upswing masked the long-term decline of British capitalism. For example, Britain’s exports as a percentage of world trade fell from almost 12 per cent in 1948 to around 4 per cent in 1974. And the UK’s trade deficit rose from £200 million in 1948, to £4.1 billion in 1974.

Crisis of reformism

By now, the optimism of the past has completely evaporated. In fact, it has turned to widespread despair and anxiety for the future.

A report by the Resolution Foundation revealed that Britain has seen weaker GDP per capita growth in the years 2004-19 than at any time since the period 1919-34 – precisely the period covered by Trotsky in these writings.

The failure to invest and modernise industry meant that British capitalism has now based itself on a low-wage, low-skill service economy. The ruling class has become completely parasitic, a class of rentiers and speculators.

The failing capitalist system could no longer afford the reforms of the past. An epoch of counter-reforms and austerity has therefore opened up, and with it a crisis of reformism. Now we have reformism without reforms, and even ‘reformists’ carrying out counter-reforms and austerity.

The deep slump of 2008 marked a watershed moment. And it affected British capitalism far worse than other major capitalist economies. In 2020, the new slump, aggravated and deepened by the COVID-19 pandemic, resulted in the biggest collapse in UK output in 300 years. Only massive bailouts by the capitalist state prevented another Great Depression. But the consequences were a mountain of debt.

The idea of a recovery was short-lived. The dislocation of supply chains, the disruption of the world market, the costly war in the Ukraine, the resulting energy crisis, and spiralling inflation are pushing capitalism into a new deep slump.

Now, as always, the working class is being asked to pay the bill. But this situation has reignited the class struggle, starting in Britain, on a scale not seen in generations.

“Class War”, screamed the front page of the Murdoch papers, as Britain was hit with a rash of strikes. Even the idea of a general strike has become inherent in the situation.

Lessons from the past

Of course, while it is true that every epoch is different, nevertheless, experience is demonstrating that the knot of history is being retied – but on a higher level.

The 1920s in Britain was a period of deep crisis, especially in the coal industry, which was the key industry at the time. Britain was being undermined by stiff competition from Germany.

The ruling class came to the conclusion that the working class must be prepared to shoulder the burden of the crisis to ‘put industry back on its feet’. This meant savage wage cuts across the board.

The showdown began in the coal industry, where the coal owners were demanding big wage cuts. In 1925 the Conservative government granted a subsidy for nine months, whilst forming a Royal Commission to look into the plight of the industry.

The labour movement heralded this as a tremendous victory and called it ‘Red Friday’. But the ruling class were simply buying time to better prepare an all-out offensive against the working class. The labour leaders, meanwhile, did nothing but lull the working class to sleep and made no preparations for the inevitable showdown.

It was at this time that Trotsky wrote Where is Britain Going? In it, he analysed the position of British capitalism and the challenges faced by the working class. It is a brilliant Marxist analysis, which has many lessons for today – not least the crucial role of leadership.

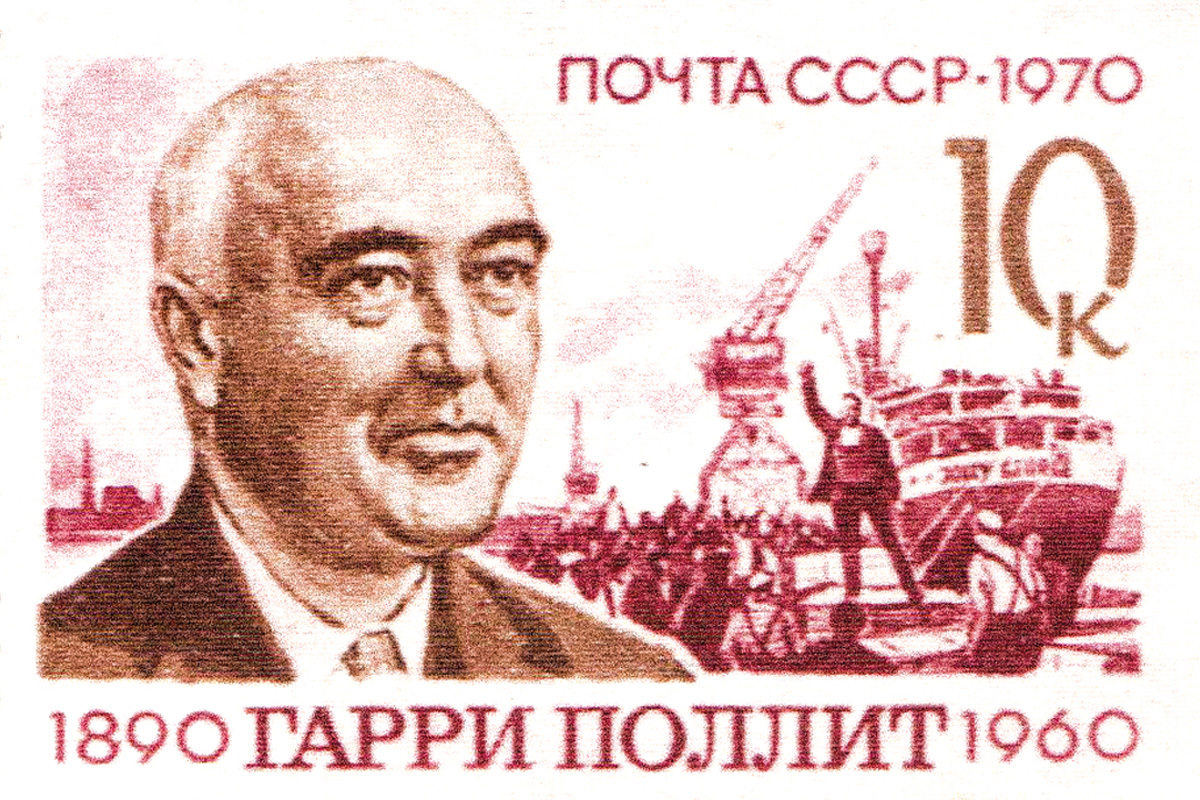

It was written as guidance for the young British Communist Party, which at that stage was struggling to assert itself.

While he dealt with the ruthlessness of the British bourgeoisie, Trotsky displayed nothing but contempt for its agents within the labour movement: the MacDonalds and other carpetbaggers. He also accurately described the shortcomings of the official ‘lefts’ in the movement.

Within the Labour Party, “there took shape the so-called left wing, formless, spineless, and devoid of any independent future”, wrote Trotsky, referring to their ideological weakness and confusion.

In contrast, the right wing drew its strength from the fact that:

“… with them stands tradition, experience and routine and, most important, with them stands bourgeois society as a whole which slips them ready-made solutions. For MacDonald has only to translate Baldwin’s and Lloyd George’s suggestions into Fabian language. […]

“The weakness of the lefts arises from their disorder and their disorder from their ideological formlessness.”

And:

“It would be a monstrous illusion to think that these left elements of the old school are capable of heading the revolutionary movement of the British proletariat and its struggle for power.”

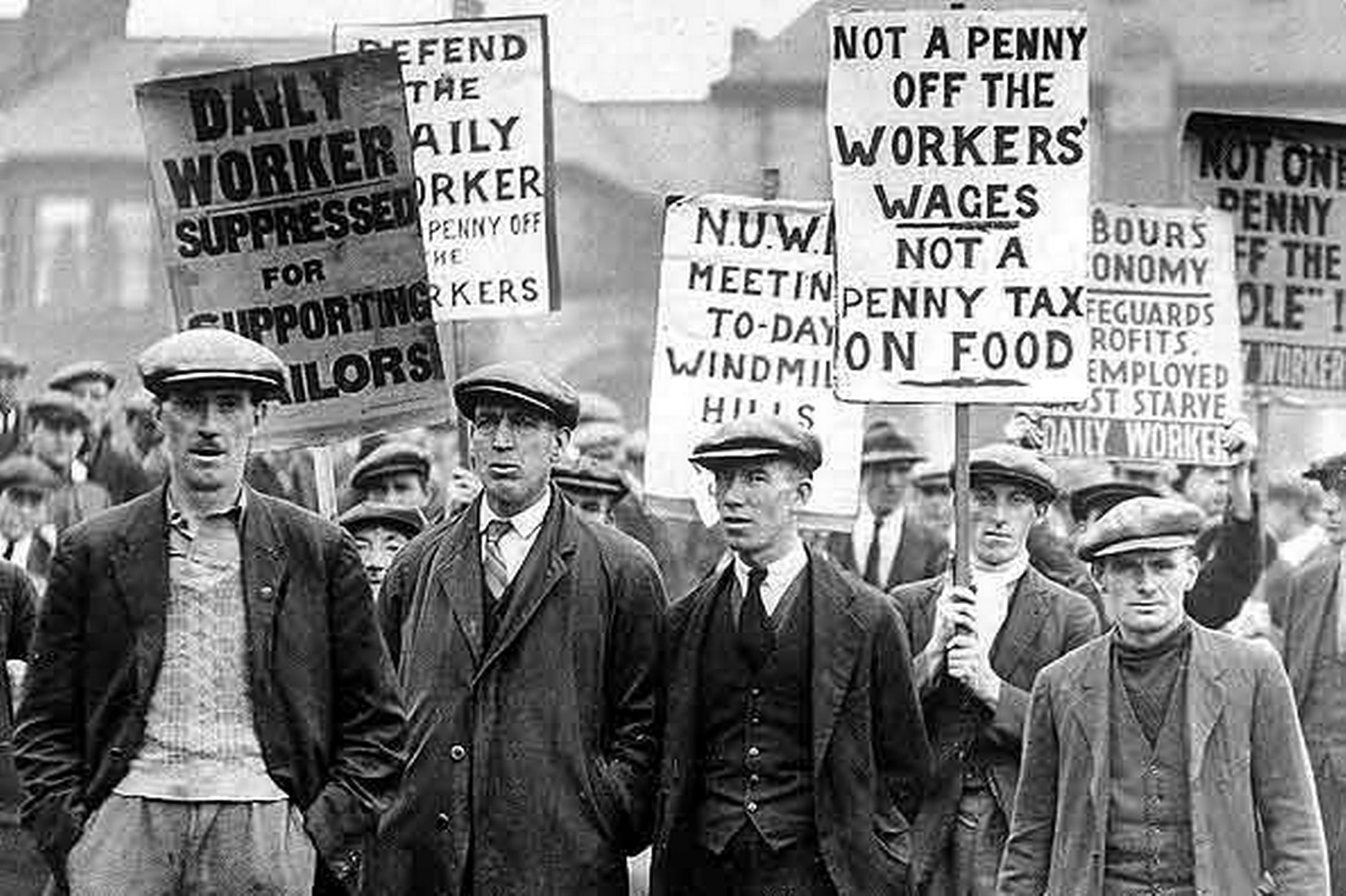

The general strike

The greatest test to confront the British working class came with the general strike of May 1926. It was called in defence of the miners, but it posed the question of workers’ power point-blank.

In such a situation, there was no room for prevarication or compromise. The strike would usher in either the greatest of defeats or the greatest of victories.

The right wing, naturally, worked to betray the strike from the very beginning. But the ‘lefts’, lacking any perspective of taking power, simply capitulated to the right.

The Anglo-Russian Trade Union Committee had been established by the leaders of the Russian and British trade unions following a visit to Russia by members of the TUC in 1924. The supposed aim of the Committee was to fight against the threat of imperialist war. This agreement provided the TUC leaders with a certain revolutionary ‘aura’, which they certainly did not deserve.

The British Communist Party leaders, for their part – under pressure from Moscow, emanating initially from the Stalin-Zinoviev faction, and later from the Stalin-Bukharin faction – took at face value the pronouncements of the TUC ‘lefts’.

This attempt to trail after these ‘lefts’, who subsequently betrayed the general strike, prompted the Communist Party leaders to issue such disastrous slogans as “All power to the General Council”.

This recognition of the General Council as the real representative of the working class only disorientated and demoralised the ranks of the party and the advanced workers that looked to it for guidance.

Following the betrayal of the general strike, the Russian Left Opposition led by Trotsky, which had been formed in 1923, argued for the breaking off of relations with the TUC leaders. The Russian party leaders of course refused.

In fact, the initiative to break with the Anglo-Russian Committee was taken by the General Council itself in 1927 – by both the right and ‘left’ trade union leaders alike.

The criticism raised by Trotsky of the Communist Party was intended as a means of drawing vital lessons, of reorienting the party, and of preparing it for the revolutionary leadership of the British working class. The growing bureaucratic reaction within the Soviet Union under Stalin destroyed this potential, however, and wrecked this promising young movement.

Today’s tasks

Today, the objective basis is being prepared for revolution in one country after another. The question of questions, raised by Trotsky throughout these writings, is the crisis of proletarian leadership. As he pointed out in Where is Britain Going?:

“[W]ill a Communist Party be built in Britain in time with the strength and the links with the masses to be able to draw out at the right moment all the necessary practical conclusions from the sharpening crisis? It is in this question that Great Britain’s fate is today contained.”

This remains the task of the hour. But now, given the increased tempo of events, it is posed with even more urgency.

We believe the republication of Trotsky’s writings on Britain will greatly assist in this endeavour, educating the future cadres, and laying the basis for a successful socialist revolution in Britain and elsewhere.