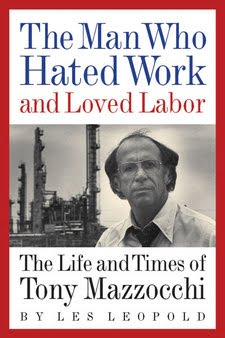

Written

by a close friend and collaborator this biography is a vivid account of an

indefatigable trade union activist in the US oil, chemical and nuclear industry.

It is extremely important in keeping alive Tony Mazzochi’s legacy and adding to

labour movement history from which thinking workers, students and youth can

draw rich lessons.

Quite

apart from this it has all the ingredients for an intriguing read, from the

battles with the corporations on one hand, to the pernicious role of the mob in

the trade union movement, the intriguing of the union careerists and the

campaign to build a fighting union from the bottom up.

The

events surrounding the death of union colleague Karen Silkwood, immortalised by

Meryl Streep in an award-winning film, are recounted. It seems too much of a

coincidence that Karen died in a suspicious car accident while working with

Tony in a sting operation to bring to light serious health and safety breaches

at a nuclear facility.

Although

all workplaces carry risks, the sorts of hazards that Tony’s members were faced

with are enough to make the reader’s hair stand on end. One of the starkest

examples was the choice faced by women workers who chose sterilisation rather

than take a pay cut with transferring away from an area with high levels of

lead-dust.

In

another horrific example, male staff at one plant had begun to develop breasts

as a result of exposure to a certain chemical. The company refused time and

time again to take responsibility but did provide protective equipment –

brassieres!

One

of Tony’s biggest achievements was the Occupational Health and Safety Act,

introduced due to a struggle spearheaded by his union the Oil Chemical Atomic

Workers (OCAW). Although far from perfect it was the first serious piece of

health and safety legislation in the US. Previously industry was

entirely self regulating.

The

aim of the Act challenged the notion that the employer could, to use the

author’s words decide ‘whether you died before your time’. As is the case with

many activists Tony has been an unsung hero, as it was his tenacity that played

the major part in winning that particular battle.

This

was bound up with Tony’s struggles inside his union to win workers to a

fighting programme. In his early union career he won over other union activists

in his union branch at the Rubinstein plant through education, establishing a

book club which encouraged thought and debate. Everything from Howard Fast to

Homer was read by the workers.

Racist

attitudes in the union were countered by winning the argument with management

of the plant that they should hire black workers, which ultimately broke down

racial divisions which had favoured the bosses.

Support

for workers struggles in other workplaces was built up to a point where

managers were unable to challenge workers arriving late due to their attendance

at other unions’ picket lines in solidarity! The effect was that managers were

under no illusions as to what workers would be prepared to do in the event of

their own disputes – such that the union did not have to take action for years

!

The

title may seem a bit awkward but as the narrative unfolds it makes perfect

sense. Tony was firmly of the opinion that ‘work was shit’ and he spent his

life avoiding it! But rather than taking up the comfort of a position as a

trade union bureaucrat with all the associated perks- and the ideas of ‘business

unionism’ – in effect collaboration with the boss – that went with it, he

worked tirelessly to build a different vision of trade unionism that he believed

could lead to the improvement of people’s lives.

This

was no easy task in the oil, chemical and nuclear industry which for years had

been dominated by the idea that campaigning for improvements in health and

safety and ultimately against the aims of the corporations – their drive for

profit at the expense of the environment and people’s health- bound together in

Tony’s view- would lead to job losses.

Tony

was convinced that there was no need for people to have to work long hours in

dangerous conditions in jobs which were largely dull and tedious. He believed

that there was more to life than this and it was the way society was organised

that prevented working people from fulfilling themselves.

As a

veteran of World War II Tony benefitted from the GI Bill of Rights which for

him proved that it was possible to provide a decent standard of living for

working people at very little cost and without the need to destroy themselves

mentally and physically by working. He pointed out that, for every dollar spent

on GI education under the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, $6.90 GDP was

created.

Tony

Mazzochi’s trade unionism and politics were inseparable as they were from him

as a person. He was, in the words of many, even his adversaries,

‘incorruptible’.

Tony’s

socialism was instinctive. He did not buy into the posturing sectarianism of

this or that left group but would never water down his principles. It is thought

that he was never a member of any group although he was close to the US Communist

Party (CP) in his early years, due to the allegiance of family and friends. He

admired their undoubted discipline and talent for organisation but he and his

family could not stomach the corrupt, bureaucratic totalitarian caricature of

Socialism that the CP came to represent due to the Stalinist reaction.

He

was not a utopian and he understood the role of trade unions as defensive

organisations. He looked for ways to tackle the prevailing ideology and in so

doing put his ideas in to action. Tony

built alliances with environmentalists, academics and progressives across the

spectrum in order to gather evidence, encourage debate and build campaigns

within his union and the wider movement.

Tony

fearlessly brought unfashionable causes into the spotlight, making it clear

that the environment and the war in Vietnam, were issues that were of central

concern to the trade union movement and bound up with the fight for health and

safety in the workplace and the fate of trade unions as militant rank and file

organisations able to defend their members’ interests.

Having

campaigned and even stood in elections for the Democratic Party he learned

through experience that they were tweedledum to the Republican’s tweedledee and

drew conclusions that a US Labor Party would be needed, which had to built by

the unions.

Countering

the union movement’s attachment to the Democrats he pointed out the ironic fact

that it was in fact only ever a Republican administration that had appointed a secretary

for labor. Perhaps this was an indication that the Republicans saw the unions

as a serious adversary! Reagan certainly did, as alluded to below.

Before

dying of pancreatic cancer in 2002, Tony spent his last years campaigning

tirelessly to build a real political voice for the trade unions in the US. Without

attacking those workers who still had illusions in the Democrats he appealed to

them by advancing the ideas of universal health care and free education for all,

which supporters of a new Party could unite around. He believed this was easily affordable and as

such not a utopian idea. After all it had been achieved in Britain following the destruction of World War

II and the US

was and is the world economic superpower.

Tony

was fighting for a Labor Party in very unfavourable conditions. The trade union

movement in the US had suffered many blows. The offensive launched by Reagan throughout

the 1980s, followed by Bush Senior and son, was not mitigated by the two Democratic

administrations of Bill Clinton in between.

Like

his UK counterpart across

the Atlantic, Reagan set out to smash an

important section of the trade union movement to send out a message to others.

After the defeat of the air traffic controllers in the PATCO union there was a

marked decline in membership of the unions. This has been replicated in Britain

following the defeat of the miners.

Leopold

has done an excellent job of bringing Tony to life and in fact, I almost felt

that I had known him! I think it would be fair to say that Tony would agree

that despite defeats the US

working class or their brothers and sisters in Britain have not been finished off.

The account of his life and times leaves a rich well of lessons that we can

draw from today.

Despite

the decline in membership of the unions, organised labour is still numbered in

millions and there are layers who will be compelled to organise in the future.

The current economic crisis demands that the working class fight for their

interests and there is no other way. The need for a party of the working class

in the US

has clearly never been more relevant. It will be on the back of mass struggle

that this will be achieved.

And

mass struggle is back on the order of the day in the US,

UK

and beyond. History may not repeat itself but it rhymes! Workers are

rediscovering their militant traditions with factory occupations and showing

contempt for the anti-trade union laws by organising ‘unofficial’ strike

action. This a testament to Tony’s fighting spirit shown throughout the book. I

urge you to read it.

ISBN:

978-1-933392-64-6

Chelsea

Green Publishing 2007

Another view of Tony Mazzocchi from the USA

I read the review of The Man Who Hated Work but Loved Labor: the Life and Times of Tony Mazzocchi by Les Leopold, but unfortunately I have not read this book as of yet. However, I wanted to add some points from my personal experience. I am a member of the Workers International League in the U.S. and I subscribe to the British Socialist Appeal. I was also a member of the American Marxist organization Labor Militant from 1986 to 1996. Labor Militant worked with Mazzocchi on this issue of building a labor party and I thought you might find these points interesting.

The Labor Militant believed that the crisis of U.S. capitalism would lead to brutal attacks on the standard of living of the working class. This would lead to big strike battles and attempts to organize the unorganized. There would also be a bitter struggle in the unions between the leadership, with its pro-capitalist and/or reformist policies and the real needs of the rank and file members. Eventually, fighting big business on the industrial arena would also play out on the political arena and at least some major unions would form a labor party. Labor Militant would raise the idea of a labor party where-ever and whenever we could, hoping to attract the advanced section of the class to our perspective and organization. We were also willing to support or work with any section of the labor movement which took real steps in that direction.

Tony Mazzocchi had been on record as supporting a labor party. Around 1989, he and the author of this book, Les Leopold, had an op-ed article about the idea of a labor party, which was published in the bourgeois press. Also, in Virginia, a United Mine Workers member named Jack Stump, ran a write-in campaign against a sitting Democrat for the lower house of the state legislature, after the Democrats had failed to support their strike at Pittston. (In the USA you can write in candidates on the ballot paper to vote for them.) Even though the campaign was a write-in and was done on short notice, he won the election!

Labor Militant decided to launch an organization called Campaign for a Labor Party (CLP). The organization would be open to all those who supported setting up a labor party, based on the unions, which would be independent of the Democrats and Republicans. Labor Militant members would also advocate that the labor party should have a socialist program.

The opening conference was held on May 13, 1989 in NYC. Mazzocchi was invited to speak, but he stated that he would not speak unless an official union body, such as the NYC Central Labor Council or a union local, was sponsoring the meeting. Therefore, Mazzocchi did not come to the meeting. The main speakers were: Bernie Sanders, who was then the independent socialist mayor of Burlington, Vermont; the late British Labour MP Terry Fields, a Marxist supporter of the Militant Tendency; and Stephen Pybus, a Marxist who was the President of the Calgary McCaul Constituency of the NDP (Canada’s Labor Party) in Canada.

In Oakland, California, a member of Labor Militant was able to get his union local, AFSCME Local 444, to sponsor a meeting on the issue of a labor party. The meeting was endorsed by ten different locals and AFSCME Council 57. Mazzocchi agreed to speak, but he came to the meeting expecting 10 to 20 workers at most. The meeting took place on December 12, 1989 and more than 140 workers attended! Mazzocchi looked happy, but also was very surprised at the turn out.

In my opinion, it was as a result of this meeting that Mazzocchi began an organization called Labor Party Advocates (LPA). The sole purpose of this organization was for people to pay dues and advocate a labor party. There could be no discussion of what should be in a labor party program, nor would it run or support candidates that ran independent of the two capitalist parties until the formation of such a party. The LPA would also not attempt to recruit youth sections. Mazzocchi also offered to poll union members whenever the leadership of a labor body allowed him to do so. The polling consistently showed that workers would prefer a labor party over the Democrats and Republicans. Mazzocchi also stated that the LPA would only call for a founding conference of a labor party once it had at least “100,000 members.”

These restrictions made it hard to get people to join the LPA. In order to get people to join and help build a labor party, it must be explained what a labor party could do if established. A labor party could organize strike support and demonstrations to defend the class against the attacks of big business. It could run candidates to repeal Taft-Hartley (Federal anti-labor laws) and establish a free national health care system, free education and a living wage. Labor Militant got its members and periphery to join LPA and continued with the CLP until the LPA started to develop chapters. Then we worked to help set up LPA chapters.

Eventually, Mazzocchi noticed that he could not get even close to 100,000 members to join an “abstract project” to build a labor party. He allowed LPA members to group together to build the organization. Labor Militant participated in this as one of the largest forces in NYC. Ironically, Mazzocchi appointed a Communist Party (CP-USA) member to head the NYC efforts in spite of the CP-USA’s support of the Democrats. He definitely did not want the Marxists to lead this effort. However, we showed with our efforts that we were the best activists in the LPA and one of our comrades soon became a leader in the NYC chapter.

Gradually, Mazzocchi allowed the LPA to form itself as the Labor Party, but he insisted that it engage in projects like trying to get a constitutional amendment for full employment, but not engage in electoral campaigns. I was not active in the labor party after I left Labor Militant in the summer of 1996, but it is my understanding that Mazzocchi kept the labor party on the sidelines of the events in the late 1990s and 2000 and it gradually became largely inactive.

The main reason a mass labor party did not arise in the 1990s, was the role played by the leaders of the AFL-CIO. They live in the milieu of the upper middle class and serve as a transmission belt for the ideas and policies of the ruling class into the labor movement. Due to this pressure, they refused to break with the two parties of big business. Mazzocchi, to his credit, put out the idea of a labor party but he was under tremendous pressure from the labor bureaucracy. I also believe he must be seen as a product of his times including the post-war boom and the McCarthy period. Like many in his generation, these events had an effect on him. I certainly do not remember Mazzocchi raising the idea of Socialism at any meeting that I was present in.

Due to the role of the labor leaders, the fact that the capitalist economy was kept going much longer than expected by debt and the ideological offensive launched by the capitalists after the collapse of Stalinism, whatever Mazzocchi and the forces around him could do, would not have lead to a mass labor party at that time. However, I believe if he had been more flexible and more willing to clash with the labor bureaucracy, the Labor Party that did emerge could have developed as a modestly-sized national party that could have had an effect on the political situation and would have been a bench mark for a future mass labor party. Instead, it is not active in the present situation. Today, we can see the capitalist crisis unfold. This will eventually lead to the changes in consciousness and battles in the unions that will lay the basis for a mass party of labor in the U.S.

Comradely,

Tom Trottier

Bronx, NY