Originally published in the Bulletin of the Opposition in 1938, The Death Agony of Capitalism and the Tasks of the Fourth International (known as The Transitional Programme) was passed as the political platform of the Trotskyist Fourth International at its founding Congress of the same year. It remains, along with Lenin’s What Is To Be Done? and Left-Wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder, one of the most important works of revolutionary strategy ever written, and provides essential reading for revolutionaries to this day.

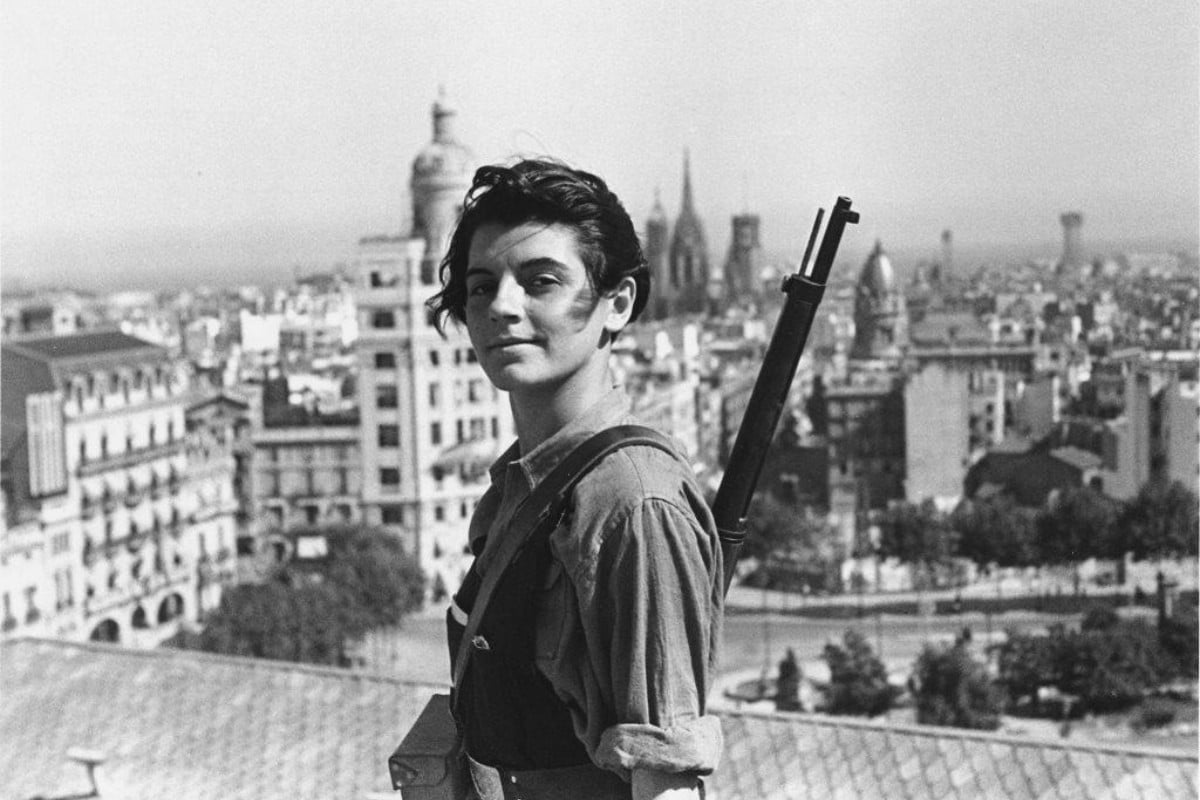

Following Russian Revolution of 1917, the world witnessed a wave of revolutionary movements throughout Europe and beyond. Inspired by the victory of the workers in Russia and the founding of the Communist International, the workers rose up in Germany, Hungary, Italy, China, Spain; every nation was in a state of revolutionary ferment. And yet, instead of the dictatorship of the proletariat and socialism, the tumultuous period of the 1920s and 1930s brought the rise of Fascism, Stalin’s purges, and the world’s descent into a war which threatened horror and destruction on a scale without precedent. It was in this dark context that Trotsky set out to write his programme for the Marxists of the world.

The first task of Marxists in this period was to understand and explain this defeat, lest future movements were to repeat the same mistakes. It is this task which Trotsky undertakes in the first part of The Transitional Programme, distilling all of the momentous events and harsh lessons of this period into the opening line, “The world political situation as a whole is chiefly characterized by a historical crisis of the leadership of the proletariat.”

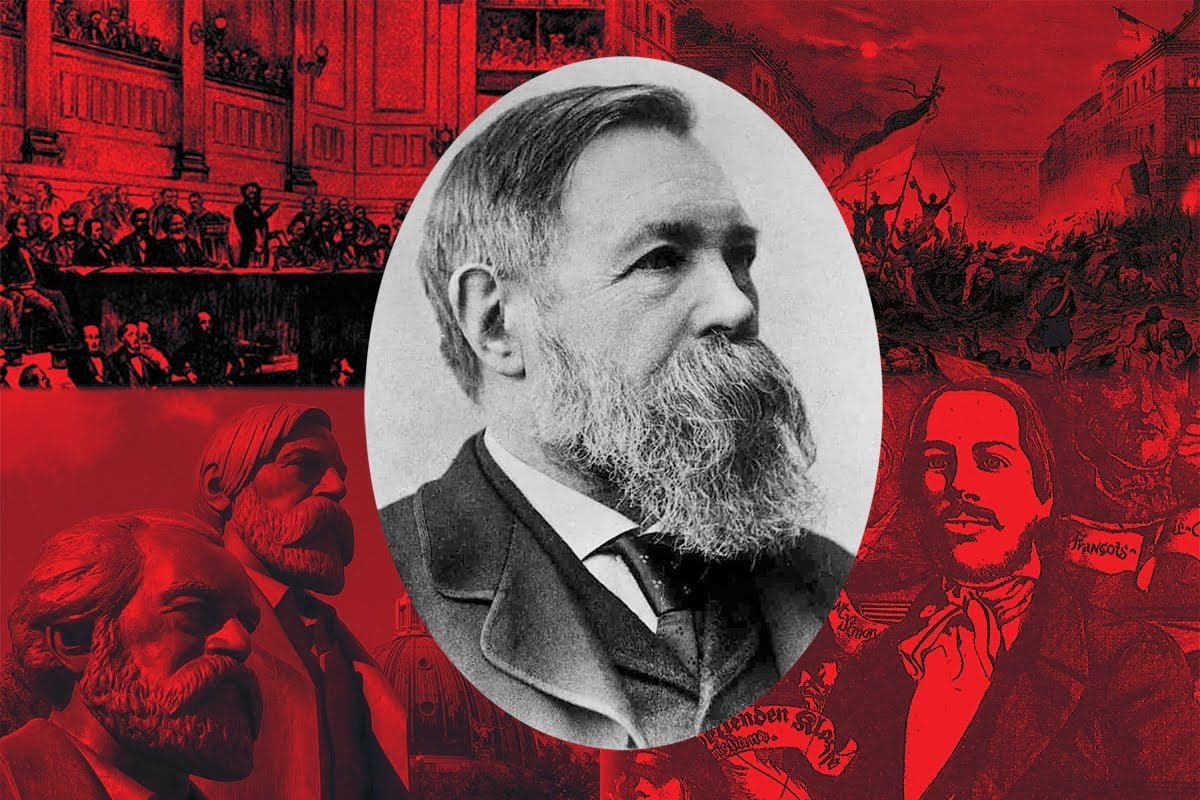

Far from the absence of the “objective prerequisites” for revolution, which according to Trotsky, “have not only ‘ripened’; they have begun to get somewhat rotten”, it was the inadequacy of the leadership of the working class, which acted as a brake on the world revolution. The key task of the Fourth International was therefore to build this subjective factor, and it is the question of how this could be achieved, the principles and tactics required of a revolutionary Marxist organisation, to which the rest of The Transitional Programme is devoted.

Transitional Demands

Predicting that the coming war would usher in a new period of revolutionary upheavals, Trotsky stresses the need to overcome “the contradiction between the maturity of the objective revolutionary conditions and the immaturity of the proletariat and its vanguard”, caused by the exhaustion and demoralisation of the older generation, and the inexperience of the younger.

To this end, Trotsky raised the need for Marxists to “help the masses in the process of the daily struggle to find the bridge between present demands and the socialist programme of the revolution”, including the use of what calls “transitional demands”, transitional because they begin with the demands and consciousness present today and conclude with the conquest of power by the working class.

Trotsky distinguishes these “transitional” demands from the old “minimum programme” of the Social Democratic parties. As opposed to the latter, which simply listed partial reforms to be won on the basis of capitalism with socialism held up as a distant, abstract, prospect, transitional demands aim to raise concrete tasks, necessary for the workers, which cannot be achieved without workers’ power, in order to demonstrate in practice the need for revolutionary answers to the workers’ problems. In short, the purpose of the transitional programme is to concretise the tasks of the socialist revolution in a way which matches the experience of workers in struggle.

The examples of transitional demands listed in the document were of course meant as a guide for Marxists operating at the time in a wide range of countries, but they still offer much that is relevant to workers’ struggles today. For example, Trotsky’s demand for a sliding scale of wages and hours, i.e. guaranteed work and a real living wage for all, is as urgent in the current period of casualised conditions and poverty wages (described in the press as a return to “Dickensian” conditions) as it was in the depression years of the 1930s. Linking this demand with that of a programme of public works (again, another demand which retains its full force today), the expropriation of the banks and the need for a unified and systematic struggle for these on the part of the labour movement, Trotsky explains that the claims of the capitalists, that such policies would ruin their businesses, will only show in practice that the choice faced by workers is either their control over the economy or their ruin under capitalism.

Trotsky also raises the need for the workers to fight using their own instruments of struggle. He calls for a struggle to raise the militancy of the trade unions and to replace their rotten leadership. At the same time however, drawing from the experience of important industrial struggles in France in particular, he explains that the trade unions can only go so far, that they are in no way a replacement for a revolutionary party, and will likely be superseded by other, broader organs of struggle as the situation becomes increasingly revolutionary (factory committees for example). He therefore warns against making a fetish of trade unionism, and presents the trade unions not as an end in themselves, but rather as “means along the road to proletarian revolution”.

Trotsky’s transitional demands are not limited to the economic field either. The demand for electoral rights for all men and women over the age of 18 (absent in many countries, including so-called “democracies” like the USA, at the time), the abolition of secret diplomacy and the “exposure of the roots of race prejudice and all forms of national arrogance and chauvinism” also form an important part of the transitional programme. All the struggles of the masses, economic or political, must be drawn together as part of a socialist programme.

Permanent Revolution

Drawing from his own personal experience of the Russian Revolutions of 1905 and 1917, as well as the experience of the failed revolutions in China and Spain, Trotsky reaffirms in The Transitional Programme his theory of “permanent revolution” as a guide for revolutionaries in all relatively backward and colonially oppressed countries.

Trotsky explains that in those countries which have not achieved the tasks of the “democratic” programme (the removal of feudal property, national independence from imperialism, formal democratic rights) the bourgeoisie is so closely tied to imperialism and landlordism that it is utterly incapable of leading a struggle to achieve a single one of the required tasks, even on the basis of capitalism. Instead, the exploited masses, led by the working class, must wage this struggle themselves and in doing so inevitably raise their own demands which go far beyond the democratic revolution and into the struggle for socialism.

Therefore, for Trotsky, in countries which still have a largely rural, peasant economy, the slogan of a “workers’ and farmers’ government” must be raised in order to forge an alliance between the two, without which a revolution would be doomed to fail. However, he stresses that this alliance must be between the workers and poor peasants in opposition to the national bourgeoisie, on the basis of the struggle for the dictatorship of the proletariat, not the establishment of an impossible liberal democracy. He contrasts this demand with the infamous policy of “People’s Fronts” which had resulted in the revolutions in China and Spain being betrayed in order to maintain an alliance with the “progressive” or “anti-fascist” bourgeoisie.

This demand, of the need for workers and peasants to break completely with the bourgeoisie not only of the imperialist countries but even their own in order to win national independence would later be confirmed the world over in the wave of inspiring struggles against colonial rule which resulted in the creation of numerous “Socialist” regimes which began on a purely nationalist basis, such as that of Cuba.

Tactics

However, it is not enough to simply arm oneself with a programme and call on workers to rally to your banner. Finding itself in a small minority in the movement, far outweighed by the dead hand of the reformist and Stalinist labour bureaucracy, the Fourth International faced the immediate task of overcoming the supremacy of the reformists and winning the most advanced sections of the workers and eventually the masses.

In order to do this Trotsky urged his followers to reject sectarianism and to orientate to the workers’ movement as they find it, repeating the advice given by Lenin to the young Communist International in the 1920s. On the question of trade unions, Trotsky explained that to refuse to join and fight within union with a (sometimes extremely) reactionary leadership was in effect the renunciation of all meaningful struggle as it would only strengthen the influence of the right-wing leaders in the absence of any revolutionary alternative, while the Marxists remain in splendid isolation.

“To face reality squarely; not to seek the line of least resistance; to call things by their right names; to speak the truth to the masses, no matter how bitter it may be; not to fear obstacles; to be true in little things as in big ones; to base one’s programme on the logic of the class struggle; to be bold when the hour of action arrives…” It is in these words that Trotsky laid out the “rules” of the Fourth International. Today, the Fourth International is long dead, but the new generation of Marxists must inscribe these rules on their banner in preparation for the monumental struggles to come!

Study questions:

- What are the “objective prerequisites for the proletarian revolution”? Why does Trotsky describe them as “somewhat rotten”?

- What is the “chief obstacle” preventing the opening up of a revolutionary situation and why?

- What transitional demands would you raise today?

- What should the approach of Marxists be to mass reformist organisation.

- What is “dual power”?

- What is the difference between “expropriation” and “nationalisation”, according to Trotsky?

- What relationship should the working class have with other oppressed classes?

- What position should Marxists take on war?

- What are soviets? How do they arise?

- How do Marxists use the slogan for a National Constituent Assembly?

- What is the difference between the “Popular Front” and the “United Front”?

- How does Trotsky characterise the class nature of the USSR? What does this mean in practice?

- Why does Trotsky stress the role of women workers and the youth?

- Why was the Communist International “dead for purposes of revolution”?

- What is democratic centralism?