Former PCS vice-president John McInally looks back at the struggle waged by the left against the right wing within the union – a struggle that has enormous lessons for today, as activists fight to transform their unions.

It is vital that we learn the lessons of the past, so as to arm ourselves for the battles ahead.

In this respect, John McInally – former vice-president of PCS (2007-17) – recalls the experience of how the left in his union defeated the old right-wing leaders, and the fight they had to carry through to the very end.

This experience has particular relevance for the left in Unison today, who are engaged in a similar battle against the right to win their union back for the membership.

Capitalism has now entered a period of multiple crises, in which instability and insecurity for the working class has become the norm. The outward appearance of Tory domination disguises an intense discontent and rage gathering below the surface. This is preparing an inevitable intensification of class struggle – one in which the trade unions will be at the very centre.

Class struggle of the most determined character, even of a revolutionary nature, will be required to defend workers conditions and rights, let alone win gains. These, as we know, can only be secured on a temporary basis before they once again come under attack.

A central task for socialists in this new period of struggle will be to fight to build democratic, member-led militant trade unions, with socialist leaderships capable of leading a fightback to defend and advance workers’ interests.

Business and service unionism; ‘partnership’; sweetheart deals; and other manifestations of the collaborationist approach of right-wing trade union leaders and bureaucracies: all of this will be increasingly exposed as workers look to defend their terms and conditions – and, through necessity, organise to remove these fetters on their capacity and willingness to struggle.

The battle between left and right in the trade unions is not a series of factional ‘power struggles’, but a reflection and concrete manifestation of the wider class struggle, which finds its expression in its most continuous and sharpest form: the workplace.

Witch-hunts

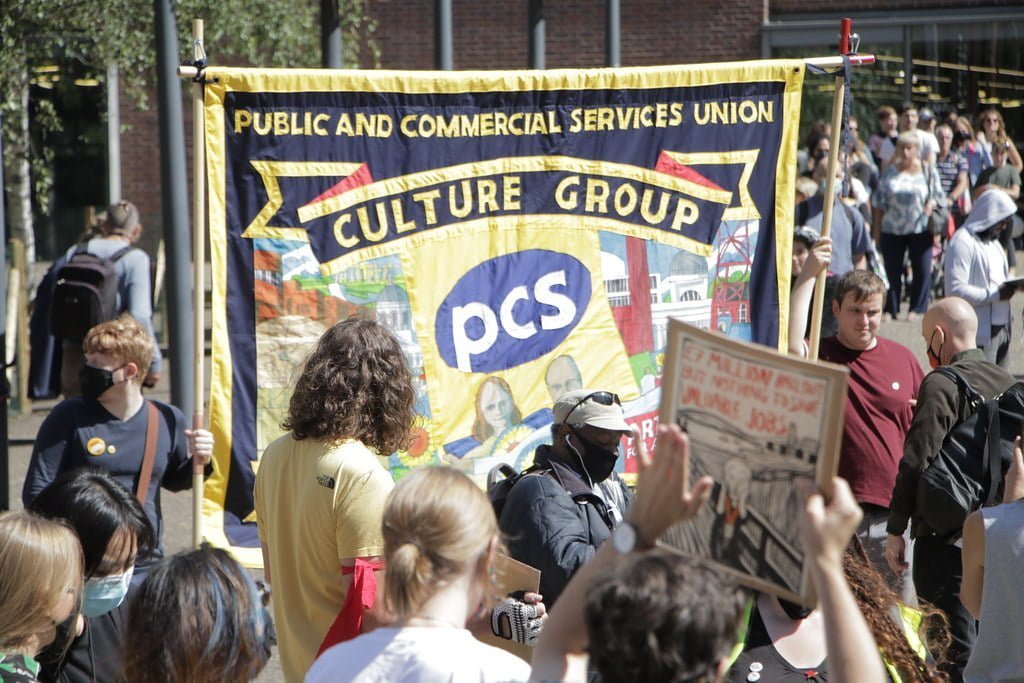

The civil service union PCS has had a socialist leadership for twenty-one years. And it has led opposition and resistance to the cuts, privatisation, and austerity policies of various governments.

But socialists do not win leadership positions in trade unions by accident – they have to be fought for. The lessons of the decades-long battle in PCS, and its predecessor union, the Civil and Public Services Association (CPSA), holds important lessons for socialists in the trade union movement today on how to confront and defeat right-wing union leaderships and bureaucracies.

The British state has had a particular interest in attempting to isolate civil service trade unionism from the rest of the labour and trade union movement. It feared the rise of militancy in this sector – particularly in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as large numbers of low-paid clerical workers who entered the service quickly organised to demand collective bargaining rights and improved terms and conditions.

In the wake of the 1926 General Strike, the government passed legislation that stopped civil service unions from affiliating to the Trades Union Congress (which many had), and also to the Labour Party (which some had).

Union activists in the service were targeted in the post-war Cold War era in anti-Communist witch-hunts, as were other trade unionists and even Labour MPs.

In the 1960s and 1970s, large numbers of working class youth, with a high proportion of women, entered the civil service. This proletarianisation of the social base of the workforce occurred just prior to the end of the post-war economic upswing; just before the ruling class implemented in earnest its long-term cuts and privatisation strategy.

This change in the workforce – alongside the new period of attacks – led to greater levels of activity, as demands for the unions to defend members’ terms and conditions grew.

‘Moderates’

It was under these conditions that the right wing in CPSA, always organised in some way or another, established the ‘Moderate’ grouping from earlier formations, like the ‘Daylight’ group and Catholic Action.

The ‘Moderates’ were the voice of the government, the state, and big business within CPSA. They strenuously opposed the idea that public sector workers should take strike action to defend themselves.

They also opposed unity with other trade unionists in fighting for the wider interests of the wider working class. In fact, those members who advocated such measures were regarded as enemies not only of the union but of the state.

Despite the right-wing claim to speak for the ‘ordinary member’, and that they were simply ‘non-political’, the ‘Moderate’ faction was supported by the state, big business, and American CIA front organisations, such as the Jim Conway Foundation and the Trade Union Committee for European and Transatlantic Understanding.

The CPSA’s right wing were also closely associated with their co-thinkers in the trade union movement; figures like Frank Chapple of the electricians union – a ruthless opponent of the left.

In 1975, ‘Moderate’ leader Kate Losinska set out in no-nonsense language the tone for future battles with the left within CPSA when, at a Reader’s Digest event, she called for action to prevent a Marxist take-over in Britain.

“With their massive and covert recruitment of public sector employees – nearly 10% of the active membership of my union now supports the militant-left – Marxists are simply following a blue-print that helped bring control in Eastern Europe,” claimed Losinska.

She went on to specifically identify public sector strikes, a relatively recent phenomenon, as warning signs. “Were local and central government paralysed, extremists could conceivably take over the whole country,” she warned.

“The biggest casualty of Marxist militancy has been the tradition that public servants would, whatever their grievances, carry on with their duties,” Losinska continued, adding that:

“Our hard-pressed security forces now face many new tasks. At one time they were mainly concerned in catching traitors passing state secrets to Soviet bloc countries. Today they must also check the subtler sabotage of Trotskyists prepared to do anything to discredit the state.”

These comments are quoted at length because they graphically illustrate the ‘Moderates’ political and ideological loyalties. In their defence of the establishment and in their battle to protect the state, i.e., capitalist society, all was permissible – including witch-hunting socialist and militant trade unionists as ‘enemies’ of the state.

The anger of trade union activists at these widely publicised comments led to a motion of censure against Losinska at the union national conference. In response, Losinska took legal action to stop the motion from being debated.

A censure motion is a mechanism of democratic accountability that allows the conference – which is the parliament and ruling body of the union – to demonstrate its disagreement with, or disapproval of, the actions of the executive or elected union officials.

It is an important and even essential element of a genuinely democratic organisation where opinions should and must be openly expressed. The use of the courts to stop the censure was a serious attack on union democracy; a method that was to become a frequently used weapon in the right wing’s arsenal in their attempt to silence all opposition.

Militancy

In a period of deepening class conflict, it was a priority of the state to suppress militancy in the civil service. CPSA had only adopted a strike policy in 1969 and some strikes followed.

A CPSA Broad Left was formed in the late 1970s, with the Militant comrades playing a key role in its foundation. The formation of an organised and committed socialist rank and file was a critical necessity in mobilising a serious opposition to the ‘Moderates’, whose aim was to police the members, drive down expectations, divide and demoralise, and collaborate with government attacks on conditions.

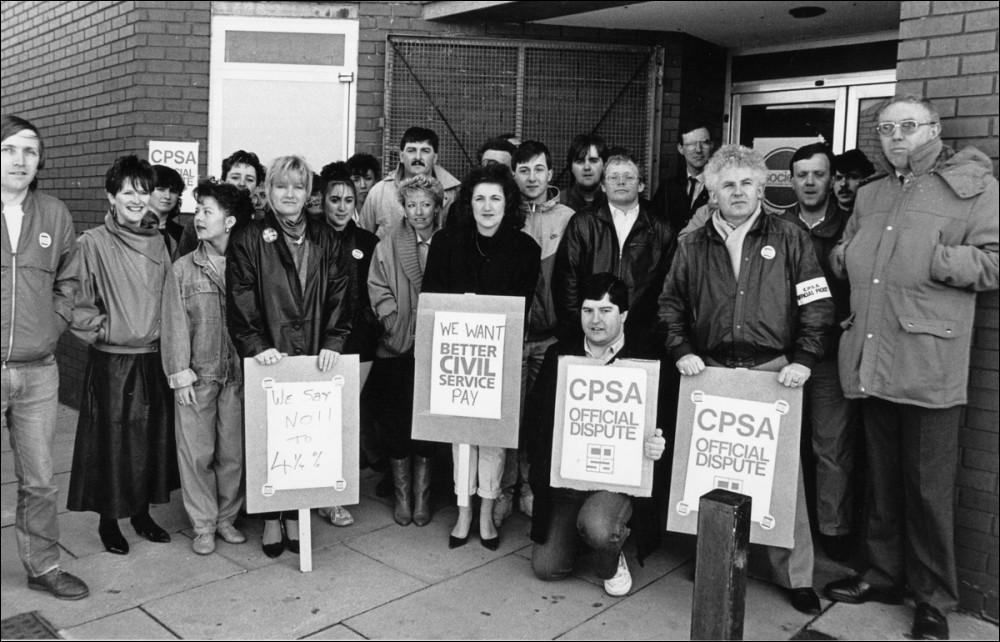

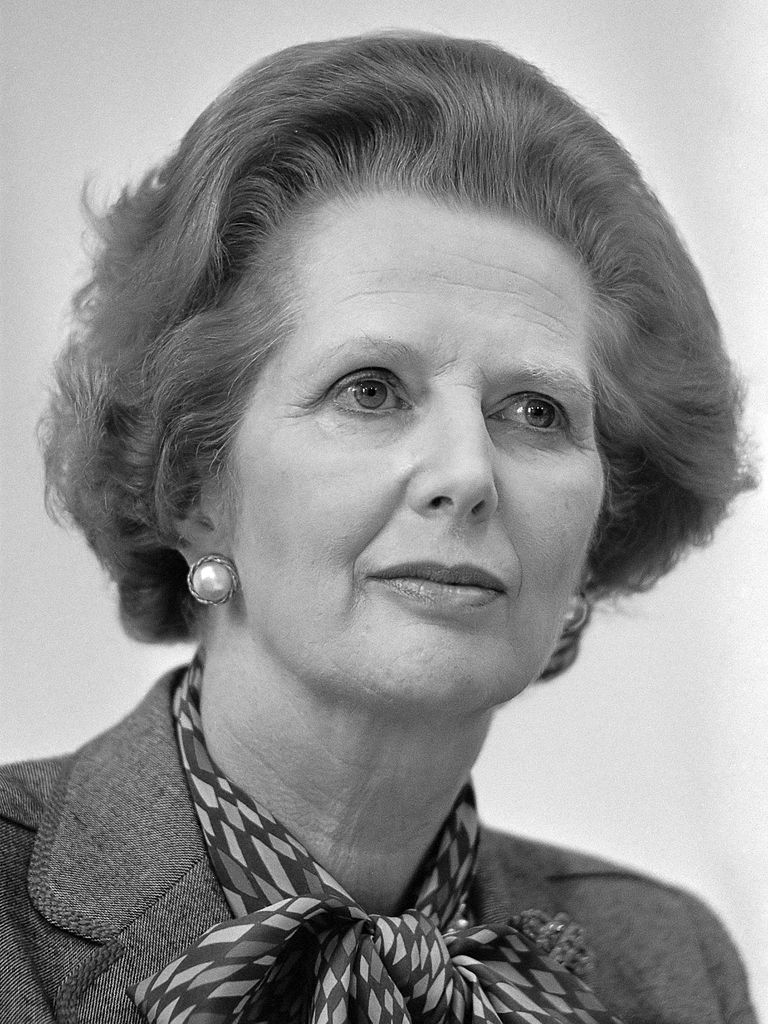

The election of Thatcher’s Tories in 1979 led to an inevitable clash with civil service unions, including CPSA, when members demanded industrial action against attacks on their pay.

Our 26 week dispute ended in defeat – mainly because the ‘Moderates’ refused to extend the action beyond selective strikes of a relatively small group of members. As a result, this failed to generalise and mobilise the full power of the union in pursuit of a strategy to win, rather than one just to ‘settle’ on the government’s terms.

The ‘Moderate’ leadership of the union simply ignored clear instructions from the union’s conference to escalate the action.

While the government won the dispute, they were deeply shaken by the potential industrial power of civil service workers, where even limited strike action had paralysed the country and billions had been lost in government revenue.

The ‘Moderates’ also understood this, and were determined – while they held power, which they did except for two brief one-year terms – to resist calls for national action.

Sabotage

The ‘Moderates’ used the most corrupt methods to hold on to power, with the full backing of the press and media in particular. In this period of heightened class war, including the miners’ strike, the establishment knew the value of their allies in the trade union movement, as well as in the Labour Party.

But CPSA members were under continuous attack, and no more so than in those areas in which the Tories were waging open class war against the most marginalised and unorganised sections of the working class, the unemployed, and those on other benefits.

Despite their best efforts, however, the ‘Moderates’ could not fully hold back the struggle in the more militant sections of the union – in particular, workers in benefit delivery areas like the Departments of Employment and Social Security, which were at the sharpest point of attack.

Under membership pressure, the ‘Moderates’ were forced to sanction a series of local and group strikes, some of a very fierce and extended character: the year-long Newcastle Shift-workers dispute; three-month Easterhouse Staffing Dispute; six-month Caerphilly DHSS dispute; and the year-long Screens dispute.

Victories were won. But more often than not, the ‘Moderates’ derailed and sabotaged action, and they strenuously refused to sanction generalised union-wide coordinated action against attacks. The Tories exploited this situation, ripping up key national agreements, including national pay.

Pressure

The ‘Moderates’ deliberately portrayed CPSA as the ‘Beirut of the trade union movement’, claiming it was under ‘siege’ by ‘left-wing extremists’.

The policies of the union’s Broad Left on pay, privatisation, terms and conditions, and so on, were regularly carried at the union’s national conference. But the ‘Moderates’ refused point-blank to carry out these democratically-decided conference policies.

The clear aim of the right wing was to create a culture of division and instability in the union, so as to prevent any organised fight-back against government assaults.

The pressure was building among members, however, who demanded action to defend their conditions.

Calls for the implementation of union democracy and leadership accountability became a principal demand of the left – and not in any abstract sense, but in the most concrete form. In refusing to carry out conference policy, the left explained, the right wing were allowing the employer a free hand in attacking members.

Rigging

As explained, the ‘Moderates’ maintained power by the most corrupt methods. Ballot insert papers for yearly union elections carried their designations of candidates. While their list was described as ‘Moderates’, the Broad Left was labelled as ‘left-wing extremist’.

In this, they were consistently helped by their friends in the gutter press, who carried red-scare stories during the ballot period about the ‘extremists’.

When elections didn’t go the way they wanted, they simply re-ran them – most notoriously when Broad Left candidate and Militant supporter, John Macreadie, won the 1986 general secretary election.

A re-run took place against the backdrop of a vicious press campaign, especially in The Sun, ‘exposing’ the ‘left wing extremists’ who wanted to ‘take over’ civil service trade unions. While Macreadie lost in the re-run, he was subsequently elected deputy general secretary of the union.

The release of Cabinet Office papers thirty years after these events showed that Thatcher’s Downing Street office planned to block Macreadie from negotiations on the grounds that “subversives cannot be tolerated in such jobs”.

In 1993, when Macreadie opposed ‘Moderate’ Barry Reamsbottom in the subsequent general secretary election, the outgoing general secretary, John Ellis, accidentally let it slip at the national executive committee that the delayed announcement of the result was due to the last minute arrival of about 3,000 ballot papers.

As Reamsbottom glared at Ellis, a voice rang out from a Broad Left NEC member, “that’ll be the MI5 vote then!” Reamsbottom ‘won’ the election by just over 3,000 votes. Activists knew that ballot-rigging was taking place, but getting ‘legal’ proof is always a difficult matter.

Victimisation

Victimisation of left-wing opponents was common-place in the union, including the shutting down of branches who dared to challenge the ruling clique.

Activists at Newcastle Central Benefits Office were framed on phoney charges of misusing union funds. These activists were driven from office, and the ‘Moderates’ attempted to expel them from the union and leave them at the mercy of the employers.

The employers would have used the first opportunity to sack these strike leaders, such as Doreen Purvis, as a warning to others who might dare to challenge the status quo. But CPSA’s constitution allowed a right of appeal to national conference in such cases. Conference delegates, disgusted by this treatment of such self-sacrificing activists, overturned the national executive committee.

In 1993, Broad Left activist Amanda Lane led unofficial action of jobcentre workers against the advertisement of sacked print-workers’ jobs in Bristol. The right wing refused to give support to this inspiring act of solidarity, and instead collaborated with the Employment Service in sacking Amanda and a striking probationer. ‘Moderate’ leaders said “they got what they deserved”.

The purpose of such intimidating behaviour was clear – challenge us and we will destroy you.

Such behaviour has a political purpose; it is meant to stop members becoming campaigning activists. But in both these cases and many others, the left organised the strongest possible opposition to these betrayals: fighting back in the branches and departmental groups; organising speaking tours; literature; motions to conference; building links with activists from other unions and campaigns.

This fightback and the sacrifices made by activists, like those in Newcastle and Bristol, had a tremendous impact, building a hardened core of activists who understood the class nature of these battles.

The ‘Moderates’ weren’t simply nasty and unpleasant people – they were the representatives of the ruling class and big business in our union. The fightback against witch-hunts and the solidarity it created was one of the strongest material factors in the subsequent defeat of the right wing.

United front

Right-wing leaders and union bureaucracies can hold power for extended periods when activity is low and there is a degree of stability. But when workers are under attack, and are demanding a militant response from their unions, such ‘leaders’ resort to the most repressive measures of the type outlined above.

Right-wing leaders and union bureaucracies can hold power for extended periods when activity is low and there is a degree of stability. But when workers are under attack, and are demanding a militant response from their unions, such ‘leaders’ resort to the most repressive measures of the type outlined above.

The right wing are always organised in one form or another. The only way they can be defeated is by a conscious militant and socialist rank and file, organised on the basis of the united front.

Such a front is when socialists of differing opinions work together to defeat the common enemy, on the basis of a commonly decided programme and policies, while retaining their respective identities and aims.

Such left formations represent an essential factor in this struggle between socialists and the right wing. Without these, the opposition to entrenched bureaucracies can only ever be of a scattered form.

The Broad Left in CPSA, and now Left Unity in PCS, played and still play this role. The left’s starting point was a commitment to socialist principles and policies, and ensuring those policies and campaigns are directly relevant to the issues facing members.

Such policies included opposition to the major attacks like cuts and privatisation; fair and equal pay; national pay bargaining; and equality: all of which are practical issues facing members in their daily working lives.

Initially, the left supported the unions affiliation to the Labour Party – a recognition that industrial and political struggles are integrally linked, up until the victory of the Blairites and the formation of New Labour.

In defiance of the right wing’s assertion that the union should restrict itself to ‘union issues’, i.e. terms and conditions, the left always followed a proudly internationalist approach, supporting many international campaigns, including the anti-apartheid struggle; opposing the sectarian division of workers in Northern Ireland; and, always standing against discrimination and racism.

Transformation

Left Unity organised in every area, at branch, group and national level, holding a yearly conference to decide policy and choose its candidates for different positions. Most significantly, a tradition of struggle was built, and comrades took the simple view that the union could be won from the Moderates – and so it was.

Left Unity organised in every area, at branch, group and national level, holding a yearly conference to decide policy and choose its candidates for different positions. Most significantly, a tradition of struggle was built, and comrades took the simple view that the union could be won from the Moderates – and so it was.

In 2000, Mark Serwotka was elected PCS general secretary, followed closely by the election of Janice Godrich as president.

Such was the determination of the ‘Moderates’ to retain power and prevent PCS becoming a democratic, campaigning, organising union, they illegally tried to overturn Mark’s election by dragging the union through the courts, costing the union tens of thousands of pounds in the process.

Both Mark and Janice took the financial risk of losing their homes in standing up to the ‘Moderates’ in the High Court. The right-wing coup was defeated, and a Left Unity majority was subsequently elected to the union’s national executive.

While the legal victory in the High Court was critical, it could not have been won without the mass mobilisation in the union of the membership itself. The judgment was a legal recognition, not simply that the ‘Moderates’ had acted illegally, but that politically their role in controlling and policing the activists and membership had become unsustainable.

PCS has become a fighting, democratic union that has been at the forefront of struggles against attacks on its members and working class. The left has held office ever since that time.

The capitalist class and their agents – the right-wing union bureaucracies – expend enormous energy attempting to discredit and destroy socialists in the trade union movement. They appreciate, perhaps even more clearly than many on the left, the significance of the role played by socialists, particularly in terms of posing a socialist alternative to their exploitative profit system.

In building resistance, organising fightbacks and so on, the left also builds and develops the class consciousness, confidence, and combativity of activists and the membership. This, in turn, serves to build traditions of militant opposition to employers and governments in individual unions and across the movement.

In this period of developing class struggle, socialists should be more confident than ever that the conditions for building a fighting democratic trade union movement have never been more fruitful, or necessary. In doing so, they are preparing the very forces for changing society itself.