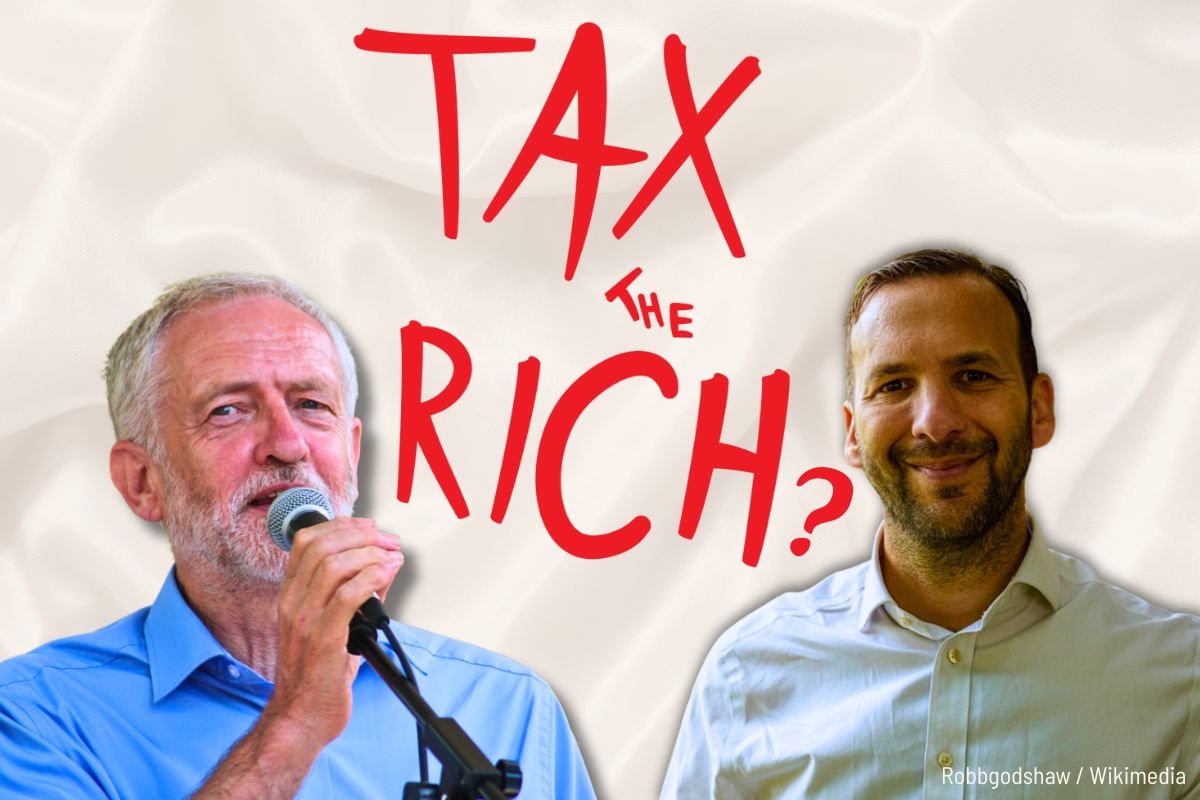

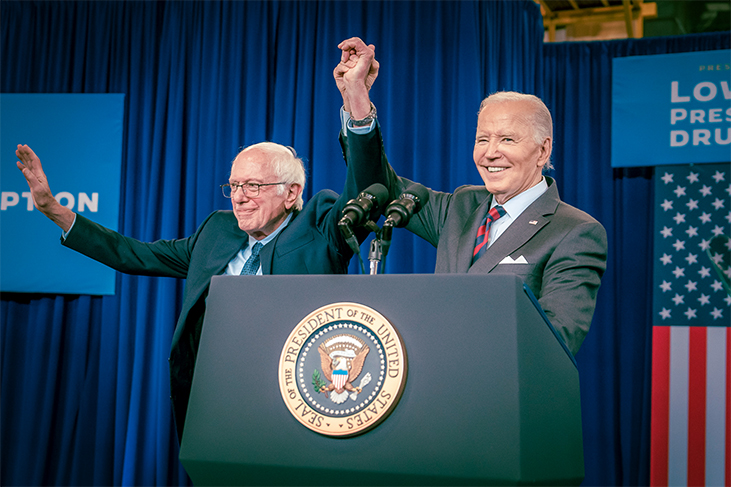

In recent months, left-wing figures have made headlines around the world. From Zohran Mamdani and Bernie Sanders in the US, to Jeremy Corbyn and Zarah Sultana in Britain, outspoken self-described socialists are capturing significant attention with their claim to be able to find simple solutions to the problems the working class face.

Yet this phenomenon is not new. Reformism – the idea that the horrors of capitalism can be eliminated without the system being overthrown – has long played a lamentable role in the workers’ movement internationally. All communists must understand the limits of reformism, but beyond this, we must be able to expose them in the eyes of workers and youth who currently follow reformist leaders.

This is the question taken up in the editorial of issue 50 of In Defence of Marxism magazine, which we publish below.

The new In Defence of Marxism magazine, with articles themed around the struggle between reformism and revolution, is out now!

View this post on Instagram

The central thread of our lead article in this issue, Lessons from Greece, is the problem of reformism: the belief that the ills of society, such as war and poverty, can be eliminated gradually, without the revolutionary overthrow of the capitalist system.

This most commonly expresses itself in the argument that the workers’ movement should limit itself to fighting for whatever is most immediately achievable. With each small victory, it is argued, the working class becomes both better off and more powerful, passing slowly but surely along the road towards its emancipation. Any discussion of the ‘final goal’ of the movement, such as socialism, thus becomes academic.

To many, this appears as a more realistic and ‘practical’ alternative to fighting for socialist revolution. After all, it promises change without the risk of violence or instability of any kind.

At times these arguments may even have a ring of truth to them. During periods of substantial capitalist upswing, the bosses have been able to afford a number of significant democratic and social reforms, at least in the advanced capitalist countries. The period of the rise of Social Democracy, leading up to the First World War, was one such period. As was the so-called ‘glorious thirty years’ that followed the end of the Second World War.

But history shows that peaceful and gradual progress is impossible under capitalism. Periodical slumps throw the whole system into crisis. And in the period of capitalism’s decline, these slumps have become deeper and longer-lasting.

Crisis

The twentieth century revealed how quickly reformism turns into its opposite. In Europe, the birthplace of Social Democracy, the period of prosperity was eventually replaced by mass unemployment, civil war and, in many places, fascism in the period leading up to the Second World War.

By binding the aims, the methods, and even the outlook of the workers’ movement to the structures of capitalism, the reformists were unable to defend past gains, let alone win new ones. Worse, many collaborated in imperialist wars and attacks on workers to maintain the stability of their own capitalist states.

Trotsky wrote in 1935:

“Without reforms there is no reformism, without prosperous capitalism, no reforms. The right-reformist wing becomes anti-reformist in the sense that it helps the bourgeoisie directly or indirectly to smash the old conquests of the working class.”[1]

Today, the crisis of capitalism also expresses itself as the crisis of reformism.

Since the end of the post-war boom in the 1970s, the gains of the working class have been slowly and painfully stripped back all over the world. Reform has turned to counter-reform. The same Labour Party that introduced ‘cradle to grave’ welfare in the 1940s is now trying to slash £5 billion in disability support payments.

In the wake of the 2008 crisis, millions of workers and youth turned to the left, spurring the rise of new movements across the world. Syriza in Greece, Podemos in Spain, Corbyn in Britain, Mélenchon in France, and Sanders in the US all attracted mass support by calling for radical change – often invoking ‘socialism’.

However, all shared the illusion that capitalism could be fixed through clever policies and state intervention. Despite their socialist rhetoric, their aim was to regulate capitalism, not abolish it. Austerity was, and is, seen as a choice, driven by nasty ‘neoliberal’ ideology, not as the necessary result of capitalist crisis.

None have delivered a single meaningful reform. In Britain, Corbyn capitulated to right-wing pressure on antisemitism and ‘Brexit’, leading to the destruction of his movement.

Sanders has endorsed every candidate put forward by the Democratic establishment since 2016, in the name of “keeping out Trump”.

In Greece, Syriza won a historic mandate to oppose austerity, only to capitulate to the demands of international finance capital, with horrifying consequences for the Greek masses.

In every case, faced with serious resistance from the ruling class, the left reformist leaders retreated.

As a result, the ‘left’ has been completely discredited. But the rage at the base of society has not disappeared. Instead, a significant section of the working class has therefore turned to figures like Trump, ‘Reform UK’, and ‘Alternative für Deutschland’, in the hope that they will offer a way out of the crisis.

Betrayal

Why did this happen? The reason can be summed up in the words of Trotsky:

“Whoever worships the accomplished fact is incapable of preparing the future.”[2]

The outlook of all reformists is characterised by the crudest form of empiricism. Indeed, the reformists themselves proudly boast of their ‘pragmatism’. They take as their starting point the immediately available ‘facts’, and then base their entire strategy on this foundation.

The ownership and control of the economy by the capitalist class is an undeniable fact; the existence and power of the bourgeois state is, likewise, a fact. In the so-called ‘liberal democracies’, the passage of legislation through parliament, universal suffrage, trade unions and so on, are all a part of the facts of life.

That the working class exists is something that most reformists would acknowledge as fact. But the idea that the working class could replace the bourgeois state and run society by itself is rejected as ‘utopian’. Why? Because the workers are not already doing it.

Accordingly, the bourgeois state becomes ‘the state’ in general; bourgeois democracy becomes ‘democracy’ in general; capitalist relations become ‘the economy’ in general; the ideological principles of the ruling class, such as its moral code, become universal ‘values’ and ‘morality’ in general.

In short, to the reformist the capitalist order is order itself – the only order that exists, and the only that can exist. Therefore, anything that threatens the collapse of this order is unthinkable.

This is why reformist leaders often fear the very movements they unleash. For them the working class is not a revolutionary force to be mobilised to topple the existing order; it is a mass to be ‘represented’. Mass mobilisations and strikes therefore amount to little more than bargaining power in perpetual negotiations with the bosses.

As soon as the foundations of the system are threatened, the reformists retreat in panic. With leaders such as these , the working class can expect nothing but defeats in the present period.

Sectarianism

Through the scientific study of the class struggle throughout history, Marxism has established that the evils of capitalism cannot be done away with without the conscious overthrow of capitalism by the working class.

Therefore, the first duty of genuine communists is to fight for the class independence of the workers’ movement. This includes the need to expose and resist all attempts to bind the movement to

the capitalist system and its institutions, like the bourgeois state. This is the “first letter of the communist alphabet”, to use Trotsky’s expression.

But, as a child of six could tell you, there are other letters in the alphabet. And it is necessary to draw a clear distinction between the reformism of the leaders of the working class, and the striving for reform on the part of the workers themselves.

Often the two will coincide. Reformists will offer reforms, and workers will follow their lead in the hope of achieving tangible improvements. Some Marxists might be tempted to dismiss the ‘reformist illusions’ of the masses. Their solution is to inform the workers that they are making a mistake, that their leaders will betray, and that they should not waste their time electing reformist politicians.

This is all well and good in the abstract. After all, such an argument would be based on a profound truth – that reformism in a period of capitalist crisis cannot provide the reforms demanded by the masses. But it would still be utterly self-defeating and false, precisely because it is so abstract.

To simply lecture the working class on the need to overthrow capitalism, without connecting this general truth to the concrete demands of the living movement, is the hallmark of sectarianism. As Trotsky explained:

“The sectarian looks upon the life of society as a great school, with himself as a teacher there. In his opinion the working class should put aside its less important matters, and assemble in solid rank around his rostrum: then the task would be solved.”[3]

Consciousness

It is not enough to assert that workers must become revolutionary. It is necessary to understand how revolutionary consciousness actually develops. And it develops dialectically, in dramatic leaps, driven by the struggle to change society in practice, not in theory.

This is especially the case in moments of crisis, when capitalism cannot afford even basic reforms.

In 1922, the Communist International observed:

“Given the general situation of the workers’ movement today, any serious mass action, even if it starts with only partial slogans, will inevitably bring to the forefront the more general and fundamental questions of revolution.”[4]

Four years later, more than 3 million British workers participated in a general strike, under the slogan: “Not a penny off the pay, not a minute on the day”. What began as a defensive struggle against the onslaught of the bosses became a direct confrontation between the working class and the full force of the British state, in which the workers could have taken power.

The potential for similar leaps exists in abundance all over the world today. In Colombia, millions of people elected Gustavo Petro as the country’s first ever left-wing president on the promise of a series of reforms to working conditions, healthcare, pensions and more.

Petro has made it clear that he wants to establish a form of ‘human capitalism’ in Colombia, not socialism. Nevertheless, millions of workers support his government and its reform programme, because they see it as an attempt to meet their urgent demands for a better life.

The problem is, Colombian capitalism is incapable of meeting these demands. Therefore, the ruling class has fought a furious rearguard battle, in the media, Congress and in the courts, to block and frustrate the reforms.

When Petro called for mass mobilisations to support a referendum, or consulta popular, on a number of his reforms, he had absolutely no intention of going beyond the limits of bourgeois democracy. Rather, he hoped to use the pressure of the masses to force a compromise from the ruling class. But Petro’s intentions are not necessarily the same as those of the workers and youth.

Spurred by Petro’s call, popular assemblies called cabildos were formed to organise the movement. The most militant layer in the assemblies has begun calling for an indefinite Paro Nacional (national strike), echoing the insurrectionary movement that defeated the right-wing government of Ivan Duque in 2021.

Fearing the potential for a mass revolutionary movement, the Colombian ruling class has made a temporary retreat, allowing Petro’s labour reform bill to pass through Congress in June. But as the crisis of capitalism deepens in Colombia, the manoeuvres of the ruling class will continue, and the radicalisation of the masses could easily grow – setting them on a collision course with the limits of Petro’s reformism.

There are points in the class struggle when the workers say, “We will not back down!” Lenin identified this as one of the essential conditions for a revolution. Such a point was reached in Greece in 2015.

When the Syriza government called a referendum on the austerity package demanded by the country’s creditors, all of the demands of the Greek masses became concentrated in a single word: “Oxi!” [No!]

What the leaders had intended as a simple vote to strengthen their position in negotiations brought the masses to their feet in a movement that could have broken with capitalism entirely and sparked a revolutionary wave in Europe.

But it is precisely here where the question of leadership becomes decisive.

As in Greece, a reformist leadership can offer no way forward. The contradiction between the words and deeds of reformists is raised to an unbearable pitch, and the movement is thrown into crisis.

The role of communists

One might ask, if the workers have been so radicalised by this point, why don’t they just dismiss their leaders and take power themselves?

If the workers could just improvise a revolutionary leadership then a revolutionary party would be unnecessary, and frankly we would already be living under socialism.

The role of the revolutionary party is not to oppose revolution to reform; it is to provide the bridge between the two. As Rosa Luxemburg explained in her pamphlet, Reform or Revolution:

“Between social reforms and revolution there exists for [Marxists] an indissoluble tie.”[5]

But in order to pass from words to deeds the party must be able to win the confidence of the majority of the working class. Questions of strategy thus flow into problems of tactics.

Communists must be able to see the world through the eyes of the working class. We must take as our starting point the consciousness of the masses as it is now, including any illusions they might have – in reformist leaders, democratic demands, the national question, etc. – and connect these with the need for the working class to control society.

If communists consider that the masses are mistaken in their demands or choice of leaders then we must tell them the truth. But not by lecturing from the sidelines. First, we must demonstrate that we are prepared to fight alongside them on whatever ground they choose to fight.

This was the approach put forward by Marx and Engels; this is what Trotsky argued for throughout his life, above all in The Transitional Programme; and it was this approach that allowed the Bolshevik Party to carry out the greatest revolution in history, in October 1917.

In the spring of 1917, the majority of workers looked to reformist parties like the Mensheviks. Rather than simply telling workers to abandon the reformists, Lenin announced publicly that these parties should take power themselves, but reject any collaboration with the ruling class and its agents. This was very effective because it reflected exactly what most workers wanted at that time, and it showed that the reformists could not fulfil the workers’ demands in practice.

Likewise, the Bolsheviks’ demands for a Constituent Assembly and the distribution of land to the peasants were not socialist demands at all; they were drawn directly from the demands of the masses. But the Bolsheviks gave them a revolutionary, transitional character when they explained that the only way these demands could be achieved is if the workers and peasants took power through the soviets (councils) they had created in the struggle, and carried them out themselves.

Lenin’s advice to the Bolsheviks was: “Patiently explain!” In this way, the workers drew their own conclusions, and turned to the Bolsheviks as the only party that could actually deliver the reforms they were fighting for. Without this, the October Revolution would never have taken place.

Our task

The coming period will contain many opportunities for revolutionary communists, but it will also contain stern tests.

If we are unable to attract the most advanced workers and youth to our banner then any claims to be a revolutionary alternative to the present leadership will be exposed as hot air. The struggle

against reformism today is nothing other than the struggle to overcome our own isolation.

In countries where revolutionary communists are only just beginning to organise, the task of winning the vanguard of the working class remains only a future prospect. But even here we must train well-rounded Marxist cadres, real communists, who are not only able to identify the errors of the workers’ leaders, but grasp the feelings of the workers themselves. It is only in this way that we can truly strengthen the forces of communism worldwide.

To understand the relationship between the struggle for reforms, reformism, and revolution, is the touchstone of any revolutionary tendency. Any that fails to understand this can at best play the role of a communist propaganda society, but never that of a party of proletarian revolution.

This is our task. If we are to succeed, we must absorb the lessons of the past.

References

[1] L Trotsky, ‘Once More on Centrism’, The Militant, Vol. 7, No. 16, 1934, pg 3

[2] L Trotsky, The Revolution Betrayed, Wellred Books, 2022, pg xviii

[3] L Trotsky, ‘Sectarianism, Centrism and the Fourth International’, New Militant, Vol. 2, No. 1, 1936, pg 3

[4] ‘Theses on the United Front’, Resolutions & Theses of the Fourth Congress of the Communist International, The Communist Bookshop, 1922, pg 36

[5] R Luxemburg, Reform or Revolution, Pathfinder, 1970, pg 5