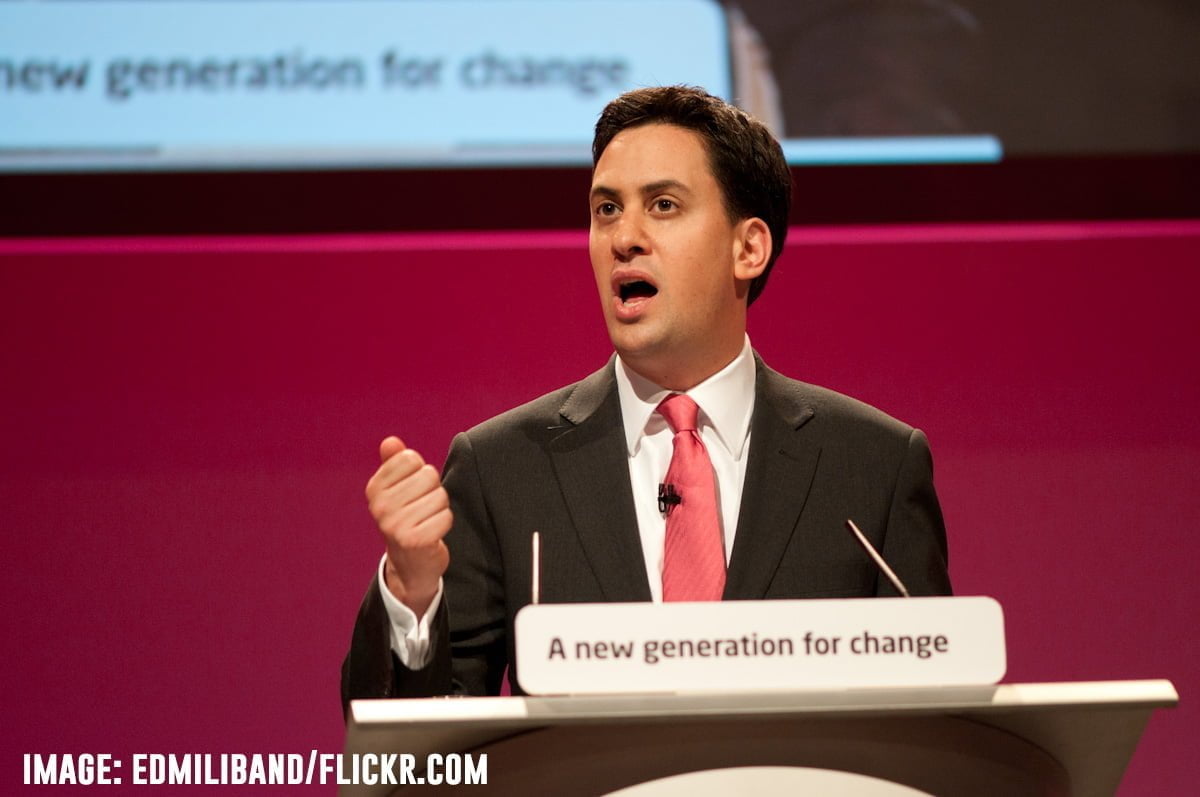

It is clear that the Tories must be kicked out; and it is only Labour that has the power to do so. However, with his endless series of political somersaults, Ed Miliband, the Labour leader, risks allowing the hated Con-Dem Coalition to continue with its programme of cuts for another five years.

With only six days until Britain goes to the polls, the two dominant parties – Conservatives and Labour – remain locked in a dead heat. Weeks of debates, campaigning, and electioneering has done little to shift opinion in favour of one or the other. It is clear that the Tories – who promise nothing but five more years of austerity and attacks – must be kicked out; and it is only Labour, in alliance with the parties of the Left, that has the power to do so. However, with his endless series of political somersaults, Ed Miliband, the Labour leader, risks allowing the hated Con-Dem Coalition to continue with its programme of cuts for another five years.

Like Janus, the two-faced god of Roman mythology, Miliband has – throughout the election campaign – constantly attempted to point in two directions at once. One minute, Miliband will be promising progressive reforms; the next, “fiscal responsibility” – i.e. cuts. Simultaneously, the potential future prime minister of Britain wishes to reassure both the 99% and the 1%.

This split personality on the part of the Labour leader is yet another clear expression of the crisis of reformism, which, especially in this epoch of capitalist crisis, cannot reconcile the contradictory and antagonistic interests of the two powerful class forces in society: capital and labour.

Ups and downs

At the beginning of April, Labour saw a surge in the polls as Miliband seemed to be standing up against the rich and powerful, promising to abolish the archaic rules whereby “non-doms” – wealthy foreign-born residents of the UK – can avoid paying their taxes. Whilst the City and the Tory press reacted with vitriol to Miliband’s promise, the pledge was warmly received by ordinary people, with opinion polls indicating a 59% approval rating for this proposal to tax the rich.

Labour’s “make the rich pay” image – and resultant lead in the polls – was short-lived, however. Within a week, the dead lock in the polls returned as Miliband attempted to out-Tory the Tories over the deficit at the Labour manifesto launch. In a sop to the bankers and bosses, Miliband tried to prove Labour’s economic (read: capitalist) credentials and reassure the markets that he would be the most “responsible” Labour leader in history, and would do “something Tony Blair and Gordon Brown never had to do” – i.e. eliminate borrowing, balance the budget, and cut the deficit; in short, that Labour would continue with Tory austerity if need be.

This quick up-and-down in the polls is a clear indication for Labour: if Miliband and co. want to get the Tories out, the way forward is to offer bold policies and a clear, left-wing alternative. It is on the basis of these demands and genuine reforms – to abolish the non-dom tax status, raise the minimum wage, end zero-hour contrasts, and get rid of the hated bedroom tax – that Labour is strongest and most supported. Any attempt to capture the mythical “centre-ground” of “fiscal responsibility” – in reality, a right-wing, Blairite programme of cuts – will only lead to disillusionment and disappointment.

Milibrand

With the election date rapidly approaching, Miliband made one last gasp attempt this week to capture the minds and imagination of ordinary workers and youth, who have thus far felt alienated and disenfranchised from the entirety of traditional politics, taking part in a recorded interview with Russell Brand for his “Trews” (true news) political video blog.

In his conversation with the comedian-turned-activist, Miliband turned 180 degrees once again, assuring Brand, under the self-proclaimed revolutionary’s questioning, that he was on Brand’s – and ordinary people in general’s – side; that he is the only political leader who would stand up against the vested interests within the capitalist system: the fraudulent bankers; the tax dodging multinationals; and the Murdoch media conglomerates.

Despite attacks from the right-wing press and from David Cameron himself, who derided Russell Brand as being “a joke”, Miliband’s attempt to appeal to the Trews presenter’s 10 million strong following of radicalised voters on social media seemed to have paid off, with Brand himself giving subtle, tacit – but not explicit – support to the Labour leader in order to defeat the Tories.

Several young respondents in a focus group organised by the Guardian confirmed the positive effect of the “Milibrand” interview on their perception of Miliband.

“I think Ed was trying to relate, and he was really trying,” stated Sheila, 17, from London. “Cameron brushed off the interview with Russell Brand as a joke. People my age feel parties aren’t genuine. A lot of my friends are like me, we think MPs don’t relate to young people. It was interesting to see him [Miliband] in such a relaxed environment, and interesting to see how he’d tackle Russell Brand, which in my opinion he did quite well!

“I think the interview will have a good effect on Ed, not Labour necessarily. Russell Brand is known as an anarchist and the interview would have helped Ed to get down to Russell Brand’s level and hear how people really feel.

“You can feel lost in the TV debates as there’s a lot of political jargon – for example people don’t really know the difference between debt and deficit. Russell Brand is a level people can understand.”

Owen Jones, the author, activist, and Guardian columnist echoed these comments made by Sheila and other similar members of Britain’s so-called “apathetic” – but, in fact, extremely radicalised – youth:

“Those sneering at Miliband for being interviewed by a much-followed figure should ask themselves: what have I done to engage disillusioned young people who feel politics has little to offer? If the answer is very little, or nothing, then perhaps a bit of humility is in order. It is a matter of deep concern that so many people have so little faith in democracy. If we are going to fix the problem, we should at least start by holding to account our cynical, self-satisfied, unrepresentative media and political elites.”

Green approval

The next day, it was the turn of the Natalie Bennett and Caroline Lucas – the Green leader and MP respectively – to be interviewed for the Trews. Again, these political leaders of the Left reassured Brand and his social media following that they would be the party that confronts the elite in favour of the vast majority.

The Trews presenter explained to these leading Greens his reasons for not voting: because the problems in society are systemic and structural; because real power doesn’t lies in parliament, but in the hands of the unelected heads of financial institutions and multinational corporations; because of “absolute indifference and weariness and exhaustion from the lies, treachery and deceit of the political class that has been going on for generations.” Such sentiments – the feeling of anger, not of apathy – are shared by millions, not only in Britain, but across the world, who feel that, fundamentally, politics and politicians do not represent them; that the system does not work for the many, but for the few.

Unlike Brand, however, Lucas correctly stressed the need to vote and to engage politically – and, in the final analysis, the need for organisation and action to take power and control out of the hands of the rich and give it back to society as a whole. “Lots of the reasons that the bankers have power or other unelected people have power,” the Brighton Pavilion MP explained, “is because politicians have given that power away. It’s not some divine right that those people have power.”

The logical conclusion, however – a conclusion not stated explicitly by the Green leaders – is for these main levers of the economy – the banks and major monopolies – to be placed under public ownership and genuine, democratic, workers’ control, as part of a rational plan of production, so that it is no longer finance and industry that controls society, but society that controls finance and industry. At the end of the day, you can’t plan what don’t control; and you can’t control what you don’t own.

Nevertheless, Brand, seemingly satisfied with Bennett and Lucas’ answers, gave a ringing endorsement to the Greens, and even went so far as to encourage people to vote for Lucas in Brighton.

The fact that both the Labour and Green leaders have sought out Brand’s approval demonstrates what an influential figure he has become in society. By giving a voice to the anger, malaise, and frustration felt by millions, especially amongst the youth, Brand has helped to express and articulate the radicalised, anti-Establishment, anti-capitalist, and even revolutionary mood that exists across the country.

However, as was demonstrated by his recently released film and by his performance in the face of interrogation from a following that is looking for leadership; that is calling out for answers; that is seeking a concrete alternative: having given this desire for change amongst ordinary people a conscious expression, this nascent revolutionary has yet to provide it with a direction. The danger, therefore, is that, like the heat within steam, this radical energy in society, if undirected, will dissipate and be wasted.

The vital task, therefore, is to build a revolutionary organisation with a clear programme and a bold, socialist alternative, that can act – as Leon Trotsky, the great Russian revolutionary explained – like a piston box in an engine, directing the steam and converting it into useful work; turning the anger that exists into a revolutionary movement that can transform society.

With his enormous following, social media platform, and influence, Brand should be acting to build such an organisation, encouraging people to get organised and active politically, and calling on the leaders of the labour movement and the Left to fight for a revolutionary socialist programme.

Saving Britain, or saving capitalism?

Miliband, having gained plaudits and popularity amongst young people for his Trews interview, managed to largely negate these gains with his subsequent performance on the final leaders’ debate (not, in fact, an actual debate, but a series of audience questions to the leaders individually).

Mere days after asserting to Russell Brand and his followers on social media that he was the man to stand up against the Tories; against the Murdoch media; against the banker and the bosses – within 48 hours, Miliband’s split personality was once again on display, as he buckled to the pressures of these same representatives of the ruling class and reassured his real audience in Westminster and the City that he would be more willing to see a Tory government than to do a deal with the SNP over the question of austerity and nuclear weapons.

Having already been outshone and put on the back foot by the parties to the left of Labour in the “challengers” debate, where Miliband again tried to assert his “fiscal responsibility” – in contrast to the popular anti-austerity message from the leaders of the Greens, SNP, and Plaid Cymru – the Labour leader was again exposed by Nicola Sturgeon, the astute leader of the Scottish Nationalists.

Throughout the debates, Sturgeon has cleverly answered the question of what role the SNP will play in a future British government, emphasising that that the SNP – with its vast bulk of seats north of the border – would be the party that most Labour voters – not just in Scotland, but across the whole of the UK – really wanted: a left-wing, anti-austerity party that would do everything possible to stop the Tories forming a government.

Sturgeon’s message has been clear: the SNP do not just have the narrow interests of Scottish independence at heart, but are a party that will represent the interests of workers and youth across the whole of Britain, keeping the Tories out and ensuring that any Labour government would not be one of “Tory-lite” Blairite policies, but of genuine reforms and progressive change.

Under pressure from Cameron and the capitalist press to “save Britain”, however, Miliband has consistently tried to prove that he – and a future Labour government – will not be “in the pocket” of Alex Salmond, Sturgeon, and the SNP. But what scares Miliband – and the British ruling class that is pressuring him – is not simply the question of a future Scottish independence referendum, which would likely be an SNP condition for entering a Labour-led government, but the question of what economic demands the SNP leaders will place on any Labour-SNP coalition. In this respect, Miliband is not so much trying to prove his credentials for “saving Britain”, but for saving capitalism.

Regardless of what the SNP leaders actually stand for in reality, their rhetoric is one of insisting that they will not support any further austerity. The situation is win-win for Sturgeon and Salmond: either they enter a coalition with Labour (formal or otherwise) and are seen to be the party responsible for stopping the cuts and pushing Labour to the left; or Miliband rejects the SNP’s overtures, and they can go back to Scottish voters and say, “see, Westminster is all about austerity – that’s why we need independence.”

Backfire

Miliband’s strategy has backfired enormously. In the latest televised leaders’ event, Miliband went so far as to categorically rule out any deal with the SNP, stating that Britain was “not going to have a Labour government if it means deals or coalitions with the SNP.”

“Let me be plain,” the Labour leader asserted, “We’re not going to do a deal with the Scottish National party; we’re not going to have a coalition, we’re not going to have a deal.”

“Let me just say this to you – if it meant we weren’t going to be in government, not doing a coalition, not having a deal, then so be it.

“I am not going to sacrifice the future of our country, the unity of our country, I’m not going to give in to SNP demands around Trident, around the deficit, or anything like that.

“I just want to repeat this point to you: I am not going to have a Labour government if it means deals or coalitions with the SNP. I want to say this to voters inScotland.”

Ever since the Scottish referendum last year, there has been an enormous disillusionment (and even outright rage) with Labour, who are now seen as “the Red Tories” north of the border, due to their alliance with the Con-Dem coalition in the “Better Together” campaign. The result has been a subsequent surge in support for the SNP: for example, the Scottish Nationalists have seen a rise in membership to over 100,000 – around 1-in-50 of the entire Scottish population.

The Labour leadership’s electoral strategy since this political earthquake has been to scare voters in Scotland into continuing to vote Labour, stating that the only way of ensuring that there would be a Labour government after 7th May would be by voting Labour. Such patronising appeals – combined with Sturgeon’s canny rhetoric – have, however, only driven Scottish voters even further into the arms of the Nationalists. And with his latest remarks ruling out any deal with the SNP, Miliband has only reinforced the worst fears of Scottish workers and youth: that he is more concerned about “saving Britain” (i.e. saving British capitalism), than about keeping the Tories out.

For if Miliband will not agree to the anti-austerity, anti-Trident demands of the SNP, then the implication is that he will have to rely on Conservative votes to push through cuts and other austerity measures – i.e. form a de facto alliance with the hated Tories. Either this, or form an actual “grand coalition” between Labour and the Conservatives – a proposal that has indeed been made by some on both sides of the Labour-Tory divide. In either case, the result will be the same: to convince Scots that Labour really are no different from the Conservatives, and to further alienate Scottish voters from Westminster politics and the idea of staying in the Union.

Capitalism’s impasse

Every decision and action taken by Miliband and the Labour leaders, therefore, is having the opposite effect to that intended: in trying to convince Scottish voters to back Labour, Miliband has only increased the support for the SNP, with some polls now indicating that the Nationalists could gain all 59 of the Westiminster parliamentary seats north of the border; in attempting to achieve a Labour majority, Miliband has in fact helped to increase the likelihood of a Labour minority government – or, indeed, even another five year of the current Con-Dem coalition of cuts; and in proclaiming himself as the man willing to “save Britain”, the Labour leader has actually served to make the possibility of Scottish independence a more probable reality.

At root, this contradictory situation that Miliband and Labour find themselves in reflects the complete impasse of the capitalist system, which – in this epoch of turbulence and endless crisis – can offer no room for compromise; no middle ground upon which reformism can safely rest. As Trotsky once remarked in relation to the global crisis and class struggle that followed the First World War and the Russian Revolution: within the confines of capitalism, every attempt to restore economic stability to the system will only lead to even greater political and social instability across society – and vice-versa.

The Marxists support every genuine reform and progressive demand contained in the Labour manifesto – the problem is that, under capitalism, such reforms and demands cannot be achieved. That is why we call for the revolutionary transformation of society; for a rational and democratic plan of production, to take the commanding heights of the economy out of private hands and thus abolish the anarchy of the market.

It is time for Miliband and co. to choose which of their two faces is the true representation of the Labour Party; to choose which class they will fight for; to choose which path to take. Whatever the leaders of the labour movement decide, the only way forward for workers and youth is along the path of revolutionary socialism.