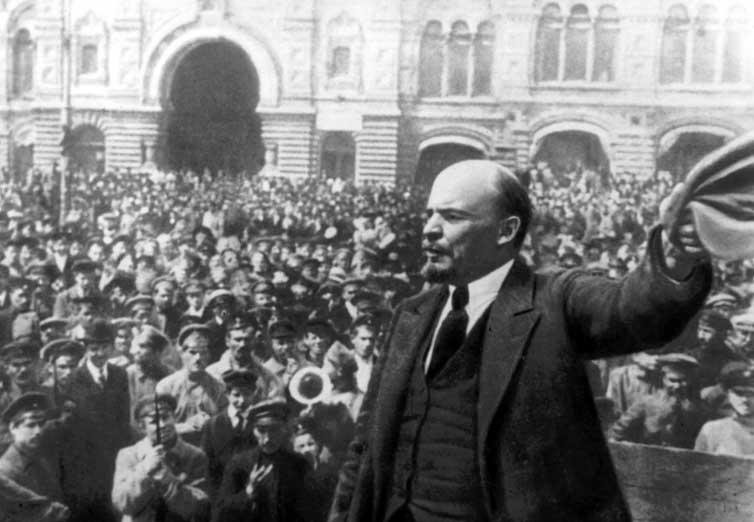

This month marks the 100th anniversary of the writing of Lenin’s great work The State and Revolution, written in the midst of the Russian Revolution to prepare the working class for taking power. To mark this important anniversary we reproduce here key extracts from an introduction of the new edition of this pamphlet, written by Alan Woods and published by the Swedish Marxists.

The State and Revolution is available as part of The Classics of Marxism: Volume One, published and available from Wellredbooks.net.

The question of the state, despite its colossal significance, is something that does not normally occupy the attention of even the most advanced workers.

This is no accident. The state would be of no use for the ruling class if people did not believe that it was something harmless, impartial and above the interests of classes or individuals—something that was “simply there” and could be taken for granted.

For this very reason, it is not in the interests of the Establishment to draw the attention of the masses to the real content of the institutions that we call the state. The constitution, the laws, the army, the police and the “Justice” system—all these things are practically taboo within the present system that calls itself a “democracy.” It is almost never asked why these institutions exist, or how and when they could be replaced.

But things are rarely what they seem. Marxism teaches us that the state (that is to say, every state) is an instrument for the oppression of one class by another. The state cannot be neutral. Already in the Communist Manifesto, written over 150 years ago, Marx and Engels had explained that the state is “only a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie.” Whoever controls this system of production ultimately controls the state power. The origins of state power are rooted in relations of production and not in personal qualities.

In early human societies the authority of the tribal chief depended on his bravery in battle, that of the tribal elders on their wisdom, etc. Nowadays, the state is run by an army of faceless individuals, anonymous bureaucrats and functionaries whose authority is conferred upon them by the office they hold and the titles they are given. The state machine is a dehumanised monster that, while theoretically serving the people, in reality stands over them as their lord and master.

The state power in class societies is necessarily centralised, hierarchical and bureaucratic. Originally, it had a religious character and was mixed up with the power of the priest caste. At its apex stood the God-king, and under him an army of officials, the Mandarins, the scribes, overseers, etc. Writing itself was held in awe, as a mysterious art known only to these few. Thus, from the very beginning, the offices of the state are mystified. Real social relations appear in an alienated guise.

This is still the case. In Britain, this mystification is deliberately cultivated through ceremony, pomp and tradition. In the USA it is cultivated by other means: the cult of the President, who represents state power personified. Every form of state power represents the domination of one class over the rest of society. Even in its most democratic form, it stands for the dictatorship of a single class—the ruling class—that class that owns and controls the means of production.

Armed bodies of men

The question of the state has always been a fundamental issue for Marxists, occupying a central place in some of the most important texts of Marxism, such as The Origin of the Family, State and Private Property by Frederick Engels, and The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte by Marx. Summing up his historical analysis of the state, Frederick Engels says:

The question of the state has always been a fundamental issue for Marxists, occupying a central place in some of the most important texts of Marxism, such as The Origin of the Family, State and Private Property by Frederick Engels, and The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte by Marx. Summing up his historical analysis of the state, Frederick Engels says:

“The state is, therefore, by no means a power forced on society from without; just as little is it ‘the reality of the ethical idea’, ‘the image and reality of reason’, as Hegel maintains. Rather, it is a product of society at a certain stage of development; it is the admission that this society has become entangled in an insoluble contradiction with itself, that it has split into irreconcilable antagonisms which it is powerless to dispel. But in order that these antagonisms, these classes with conflicting economic interests, might not consume themselves and society in fruitless struggle, it became necessary to have a power, seemingly standing above society, that would alleviate the conflict and keep it within the bounds of ‘order’; and this power, arisen out of society but placing itself above it, and alienating itself more and more from it, is the state.” (F. Engels, The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State)

After Engels’ seminal work, without doubt the book that best explains the essence of the Marxist theory of the state is Lenin’s State and Revolution, one of the most important works of the twentieth century. Written in the summer of 1917, in the heat of the Russian Revolution, it is a key work of Marxism. Here Lenin explains that, stripped of all non-essentials, the state is, in the final analysis, “groups of armed men”: the army and the police. It represents an organ of repression of one class over another.

Bourgeois legal theory regards the state as an impartial arbiter standing above classes and particular interests. This view is shared by the reformists of all varieties. It ignores the fundamental fact that the essence of every state, with its armed bodies of men, police, courts and other trappings, is that it serves the interests of one class in society: in the case of capitalism, the capitalist class.

The illusion of democracy

Under a regime of formal bourgeois democracy, such as in Britain, anyone can say (more or less) what they wish, as long as the banks and big monopolies decide what happens. In other words, bourgeois democracy is just another way of expressing the dictatorship of big business. This assertion can easily be demonstrated by the experience of social democratic governments over decades.

Under a regime of formal bourgeois democracy, such as in Britain, anyone can say (more or less) what they wish, as long as the banks and big monopolies decide what happens. In other words, bourgeois democracy is just another way of expressing the dictatorship of big business. This assertion can easily be demonstrated by the experience of social democratic governments over decades.

Social Democracy in the advanced capitalist countries still has a mass base. It has held power in many northern European countries for much of the last century and carried out many important reforms. This was possible in an era when capitalism was in a position to make concessions, while the working class was organised and could and did demand such measures. However, the Social Democracy was always careful to leave the management and control of society in the hands of the bankers and capitalists. Now that the conditions have changed, the future facing the working class is not one of reforms, but counter-reforms.

Whereas the British ruling class conceals its domination behind a thick curtain of tradition, pomp and ceremony inherited from medieval barbarism, in Scandinavian countries such as Sweden the bourgeoisie has a more sophisticated and “modern” approach. The state in these cases appears to be more homely, more humane and democratic.

But, politeness notwithstanding, the bosses remain bosses and the workers remain workers. The “politeness” of form is intended to conceal the real content of class division, oppression and exploitation. It is just as much a deception and an illusion as is the mediaeval garbage that embellishes the British state to disguise its true nature.

In Britain and other advanced capitalist countries, the illusions in democracy run deep. This fact is grounded in material conditions. Until the 2008 crisis, capitalism experienced a long period of economic growth that permitted it to grant certain concessions to the working class, and thus blunting the class struggle and creating the illusion of a peaceful democratic society.

In reality the state is organised violence. That is just as true of a democratic state, such as in Britain or Sweden, as it is anywhere else. The only difference is that the reality has been skillfully concealed behind the smiling mask of bourgeois democracy. But this illusion will not survive in the turbulent period that now opens up internationally, from which no country can remain isolated.

When the ruling class can no longer hold the working class in check by ‘normal’ means, they will not hesitate to use violence. It would be fatal to entertain any illusions on that score. To the degree that the global crisis of capitalism begins to seriously affect all countries, that mask will be cast aside to reveal the reality of police repression and state violence. The illusions in democracy will be knocked out of people’s heads by a policeman’s truncheon.

“Dictatorship of the proletariat”

In describing the transitional state between capitalism and socialism Marx spoke of the “dictatorship of the proletariat.” This term has led to a serious misunderstanding. Nowadays, the word dictatorship has connotations that were unknown to Marx. In an age that has known the horrific crimes of Hitler and Stalin it conjures up nightmarish visions of a totalitarian monster, concentration camps and secret police. But such things did not yet exist even in the imagination in Marx’s day.

For Marx the word dictatorship came from the Roman Republic, where it meant a situation where in time of war, the normal rules were set aside for a temporary period. The idea of a totalitarian dictatorship like Stalin’s Russia, where the state would oppress the working class in the interests of a privileged caste of bureaucrats, would have horrified Marx. In reality Marx’s “dictatorship of the proletariat” is merely another term for the political rule of the working class or a workers’ democracy.

Marx based his idea of the dictatorship of the proletariat on the Paris Commune of 1871. The Commune was a glorious episode in the history of the world working class. For the first time the popular masses with the workers at their head overthrew the old state and at least began the task of transforming society. With no clearly defined plan of action, leadership or organisation, the masses displayed an astonishing degree of courage, initiative and creativity. Yet in the last analysis, the lack of a bold and farsighted leadership and a clear programme led to a terrible defeat.

Marx and Engels drew a thorough balance sheet of the Commune, pointing out its advances as well as its errors and deficiencies. These can almost all be traced to the failings of the leadership. The leaders of the Commune were a mixed bunch, ranging from a minority of Marxists to elements that stood closer to reformism or anarchism. One of the reasons the Commune failed was that it did not launch a revolutionary offensive against the reactionary government that had installed itself at nearby Versailles. This gave time to the counter-revolutionary forces to rally and attack Paris. Over 30,000 people were butchered by the counter-revolution. The Commune was literally buried under a mound of corpses.

Generalising from the experience of the Paris Commune, Marx explained that the working class cannot simply base itself on the existing state power, but must overthrow and destroy it. The basic position was outlined in State and Revolution, where Lenin writes: “Marx’s idea is that the working class must break up, smash the ‘ready-made state machinery,’ and not confine itself merely to laying hold of it.”

Against the confused ideas of the anarchists, Marx argued that the workers need a state to overcome the resistance of the exploiting classes. But this argument of Marx has been distorted by both the bourgeois and the anarchists. The working class must destroy the existing (bourgeois) state. On this question we agree with the anarchists. But what then? In order to bring about the socialist reconstruction of society, a new power is required. Whether you call it a state or a commune is a matter of indifference. The working class must organize itself and therefore constitute itself as the leading power in society.

The working class needs its own state, but it will be a state completely unlike any other state ever seen in history. A state that represents the vast majority of society does not need a huge standing army or police force. In fact, it will not be a state at all, but a semi-state, like the Paris Commune. Far from being a bureaucratic totalitarian monster, it will be far more democratic than even the most democratic bourgeois republic – certainly far more democratic than Britain is today.

In Defence of October

The workers’ state established by the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 was neither bureaucratic nor totalitarian. On the contrary, before the Stalinist bureaucracy usurped control from the masses, it was the most democratic state that ever existed. The basic principles of Soviet power were not invented by Marx or Lenin. They were based on the concrete experience of the Paris Commune, and the Soviets that arose organically in the Russian Revolution of 1905 and 1917.

The workers’ state established by the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 was neither bureaucratic nor totalitarian. On the contrary, before the Stalinist bureaucracy usurped control from the masses, it was the most democratic state that ever existed. The basic principles of Soviet power were not invented by Marx or Lenin. They were based on the concrete experience of the Paris Commune, and the Soviets that arose organically in the Russian Revolution of 1905 and 1917.

The Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies were elected assemblies composed not of professional politicians and bureaucrats but of ordinary workers, peasants and soldiers. It was not an alien power standing over society, but a power based on the direct initiative of the people from below. Its laws were not like the laws enacted by a capitalist state power. It was an entirely different kind of power from the one that generally exists in the parliamentary bourgeois-democratic republics of the type still prevailing in the advanced countries of Europe and America. In one form or another, soviets, workers’ councils, or embryos of soviets have arisen spontaneously in more or less every revolution since.

A genuine workers’ state has nothing in common with the one that existed in Stalinist Russia. Lenin was the sworn enemy of bureaucracy. He always emphasised that the proletariat needs only a state that is “so constituted that it will at once begin to die away and cannot help dying away.” The basic conditions for workers’ democracy were set forth in State and Revolution:

1) Free and democratic elections with the right of recall of all officials.

2) No official to receive a higher wage than a skilled worker.

3) No standing army or police force, but the armed people.

4) Gradually, all the administrative tasks to be done in turn by all. “Every cook should be able to be Prime Minister—When everyone is a ‘bureaucrat’ in turn, nobody can be a bureaucrat.”

These were the conditions which Lenin laid down, not for full-fledged socialism or communism, but for the very first period of a workers’ state—the period of the transition from capitalism to socialism. This programme of workers’ democracy was directly aimed against the danger of bureaucracy. This in turn formed the basis of the 1919 Party Programme.

The transition to socialism—a higher form of society based on genuine democracy and plenty for all—can only be accomplished by the active and conscious participation of the working class in the running of society, of industry and of the state. It is not something that is kindly handed down to the workers by kind-hearted capitalists or bureaucratic mandarins. The whole conception of Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Trotsky was based upon this fact. Anybody can see that this programme is completely democratic and the very antithesis of bureaucratic dictatorship. Socialism as understood by Marxists is democratic or it is nothing.

Fight for revolution!

At the present time, when the bourgeoisie on a world scale has launched a savage attack against living standards, wages, pensions, jobs and conditions, it is necessary to understand that even when the working class succeeds in extracting concessions from the capitalists, these will only be temporary. What the bosses give today with the right hand will be taken back with the left tomorrow. At a certain stage this will mean an enormous intensification of the class struggle.

The truth is that the only way to solve the present crisis is through a radical transformation of society which will put an end to the domination of the big banks and monopolies. Any other solution will turn out to be disastrous. It would be naïve to imagine that the ruling class would simply remain with its arms folded in the event of a working class government that was really determined to change society. A workers’ government will be immediately confronted with the ferocious resistance of the bankers and capitalists.

Powerful union and worker organisations exist that would be more than capable of overthrowing capitalism if the millions of workers they represent were mobilised to this end. The leaders of the trade unions and reformist parties have in their hands a power that can bring about a peaceful transformation of society.

Without the aid of the reformist leaders it would not be possible to maintain the capitalist system for any length of time. The problem is that these leaders have no intention of leading a serious fight against capitalism. On the contrary, they fear such a fight as the devil fears holy water. That is why Trotsky said that, in the last analysis, the crisis of humanity was reduced to a crisis of leadership of the proletariat.

The conditions for maintaining the old politics of consensus between the working class and capital are long gone. An increasing number of activists will come to see the need for a consistent revolutionary programme. This can only be provided by Marxism.

We have a duty to remind workers and youth of the great traditions of the past and to make available to them the works of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Trotsky. Certainly, among the most important of these works is State and Revolution, a book as relevant today as when it was first written a century ago.