The highlight of the recent Labour conference in Liverpool, for many, was the call by Laura Smith MP for a general strike to bring down the Tory government.

This earnt her a standing ovation from the crowd in attendance at the fringe meeting where the Labour MP was speaking. But it also incited the rage of the establishment, who were furious at the suggestion of such militant action being raised.

Leading the attack against this call was Labour deputy leader Tom Watson, a loyal defender of the big business wing of the Parliamentary Labour Party. Watson asserted that Britain’s only previous general strike, in 1926, had been a failure, and that “most trade unionists will tell you it was an absolute disaster”.

For these careerists and right-wingers, any sort of “extra parliamentary action” on the part of the masses is doomed to failure and must be avoided at all costs. Far better, we are told, to leave any struggle to “our” representatives at Westminster who know best how to resolve things – albeit usually not in our interests.

In fact, every worker knows from experience that to win anything meaningful you have to fight. The “disaster” of the 1926 strike lay with the failure of the union leadership, who refused to use the power in their hands to defend the miners and defeat the attacks of the capitalists and their political cronies. Fault did not lie with the struggle itself.

Below is an extract from a longer article on the lessons of the 1926 general strike.

Lions led by donkeys

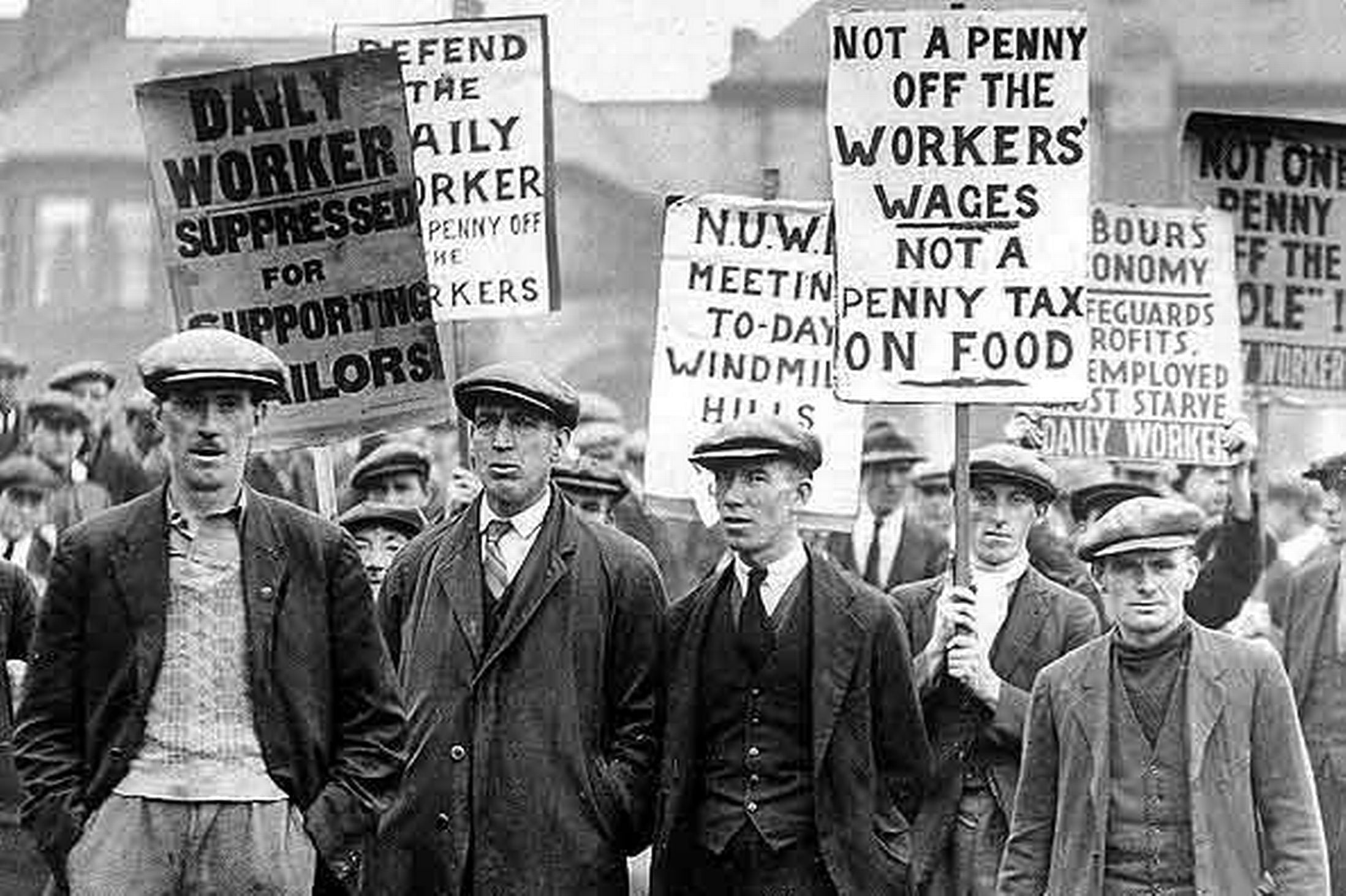

What were the actual facts behind the 1926 strike? Lasting for nine days, the strike showed the enormous power and solidarity of the working class. Four million trade unionists – out of a total of 5.5 million – responded to the Trade Union Congress’ (TUC) call to halt work in opposition to pay cuts and increased working hours for the miners.

What were the actual facts behind the 1926 strike? Lasting for nine days, the strike showed the enormous power and solidarity of the working class. Four million trade unionists – out of a total of 5.5 million – responded to the Trade Union Congress’ (TUC) call to halt work in opposition to pay cuts and increased working hours for the miners.

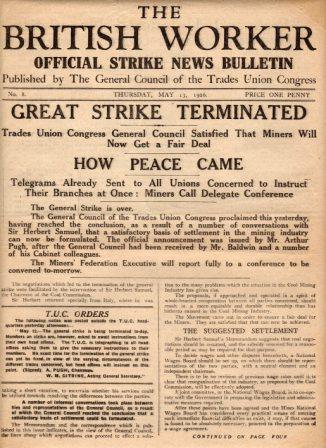

Despite the strike growing stronger and stronger by the day, however, the TUC leadership did everything they could to bring the strike to an end, resulting in a crushing defeat.

The TUC leaders, believing that they would reach a settlement with the government, had made no preparations for the strike. To their surprise, and to the shock of the ruling class, the workers showed their magnificent capacity to improvise and organise from below.

Trades Councils in every area formed Councils of Action and strike committees. Nothing could happen without the permission of the working class.

The Councils organised picketing, communications, permits for the supply of basic goods, and even workers’ defence corps to protect against the violence of the state.

Revolutionary implications

As the strike developed over the course of its nine days, it became a struggle against the government. The Councils of Action, in turn, developed increasingly into organs of self-government.

Militant demonstrations took place in all the main towns and cities. Clashes with the police were commonplace, and thousands of workers were arrested and imprisoned.

On the eighth day of the strike, the engineers and other sections of the working class were called to join the action. In many cases, workers were already out on strike before being called, such was the mood for solidarity across the working class.

Rather than fearing the resistance of the ruling class, who proved impotent in the face of millions of organised workers, the General Council of the TUC were more terrified of the revolutionary implications of the strike.

Workers’ power

A general strike inevitably poses the question of power. Either it will lead to the conquest of power by the working class, or a severe defeat for the workers.

A general strike inevitably poses the question of power. Either it will lead to the conquest of power by the working class, or a severe defeat for the workers.

Behind the scenes, the General Council completely capitulated to the government, accepting a reduction in the miners’ wages, with no guarantees against victimisation. Baldwin announced on the radio that there were “no conditions” and that the TUC had accepted this unconditional surrender.

This news came as a complete shock to the workers, who could feel the enormous power they wielded during the strike.

In response to the sell out, the railmen, dockers, engineers and other sections continued the strike, in order to prevent it from ending as a complete rout. Indeed, two days after the strike had been officially called off, over 100,000 more workers had joined the action!

Rise like lions after slumber

In contrast to 1926, a general strike today would be immeasurably more powerful. Even if Britain’s largest union, Unite, called out all its members, it would bring the country to a standstill, given that Unite organises workers in key sectors, such as power, transport and logistics.

In contrast to 1926, a general strike today would be immeasurably more powerful. Even if Britain’s largest union, Unite, called out all its members, it would bring the country to a standstill, given that Unite organises workers in key sectors, such as power, transport and logistics.

Added to that, with the power of the rest of the trade union movement, such a strike would be unstoppable. The prior condition for the success of a general strike, however, is for it to be led by resolute leaders.

The real militant history of the 1926 general strike is why the ruling class fears so much the possibility of a repeat today, and why the Blairites have responded with such anger to Laura Smith’s popular call for the labour movement to get off its knees and strike to topple the Tories.